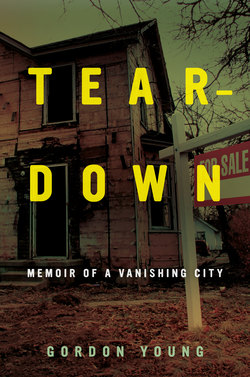

Читать книгу Teardown - Gordon Young - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

Virtual Vehicle City

I launched Flint Expatriates in the fall of 2007. It lacked just about every attribute that guarantees a large audience in the blogosphere. It wasn’t devoted to strident political views, tawdry celebrity gossip, the latest life-changing technology, or hardcore porn, unless you are turned on by graphic photos of abandoned houses, stripped bare of their aluminum siding and totally exposed to the elements. Aside from demolition crews, pawn shops, and moving companies, it had no obvious advertising tie-ins.

I wasn’t expecting a blog about a troubled Rust Belt city to be wildly popular. I was hoping it would help me come to terms with my conflicted feelings about Flint without being mean spirited, depressing, or sappy. I wanted it to be funny without making too much fun of Flint. Improbably, I hoped to cover the past, present, and future of the city from my remote publishing headquarters in the cramped living room of my house in San Francisco. If I failed, it was no big deal. I figured no one would read it anyway.

The result was a jumbled collection of posts based on my mood and what I could dig up after classes at the university or during downtime between freelance assignments. A story theorizing that Flint might rebound when water shortages forced residents of the southwest United States to move north might be followed by an item about a pair of AC spark plugs, once proudly manufactured in Flint, that had been fashioned into earrings for sale on eBay. A YouTube video that used satellite imagery to compare Flint, with its acres of demolished factories, to Ground Zero after 9/11 ran the same day as a piece on urban gardens springing up on vacant lots in some of the city’s worst neighborhoods. It was an odd mixture of hope and despair, wonky urban-planning material and kitschy cultural ephemera. Memories of the old days mingling with semi-informed conjecture about what might lie ahead. The blog was my way of thinking out loud about Flint.

As expected, the public response was underwhelming. A few comments trickled in, but I sensed that many of the three dozen hits the blog generated each day were mistakes—collectors tracking down info on flintlock rifles or cartoon fans searching for trivia on Fred and Wilma Flintstone. Then I realized that I had neglected to address a topic that would surely resonate with my elusive target audience. I didn’t have any posts about the ultimate leisure activity in Flint—getting drunk. I remedied the situation by asking Flintoids, as we sometimes called ourselves, to name every local bar, smoke-filled tavern, and dimly lit lounge they could remember. This was apparently the supreme challenge for the current and former residents of a factory town that once felt like it had a drinking establishment on every corner. The post generated more than a hundred comments, and the list of booze emporiums climbed to well over three hundred. There was everything from strip clubs like the infamous Titty City near the Chevy plant to posh joints like the University Club in the penthouse of the now-abandoned Genesee Towers, Flint’s tallest building. The names alone made you want a drink: the Argonaut, the Ad-Lib, the Beaver Trap, Thrift City, Aloha Lounge, Auggie’s Garden Glo, the Treasure Chest, the Rusty Nail, the Torch, the Teddy Bear, the White Horse, the Whisper. The sheer number was impressive, although most were now closed. A clever economist could surely track Flint’s decline by charting the year-over-year drop in bars open for business.

One of the dearly departed to make the list was the Copa, an improbably named oddity that stood out in a city where bars tended to have rustic names like the Wooden Keg, and references to Barry Manilow songs were frowned upon. Bill Kain opened the Copa in 1980 in the heart of downtown on Saginaw Street. Though Flint lived and died with the auto industry, Kain embraced diversification and catered to just about everyone, including high school kids with bad fake IDs. The Copa was primarily a gay bar, but Thursday was officially straight night, and the crowd was mixed on many evenings. In a largely segregated town, it was racially mixed, playing funk and hip-hop in a market that made Foreigner, Styx, and Billy Joel rich. There were house music nights, live rap acts, and male strip shows—attended primarily by straight women. New Wave music was a staple, and it was the only bar in town where dancing to the Tom Tom Club or New Order wouldn’t warrant an ass-kicking. (The Copa still had its share of shoot-outs and brawls, but none appeared to be caused by musical or sexual preference.)

Kain was an outspoken critic of the harebrained schemes to revitalize Flint with auto-themed amusement parks and high-end shopping projects, but the fact that he had a thriving business didn’t give him much pull at city hall. When Kain died in 1991, he was dismissed with a tiny, four-paragraph obit in the Flint Journal. The paper managed to spell his name wrong.

By writing about bars, I found my people. The number of hits jumped, and readers began sharing their thoughts on Flint. Only a few dozen had to be edited for excessive profanity. Some were heartfelt odes to venerable local institutions like Halo Burger, home of the deluxe with olives and the Vernor’s cream ale. Others celebrated local characters like Gypsy Jack, an East Sider who turned his house into a Wild West museum, complete with a jail and saloon in the basement. He sometimes dressed like a cowboy, strolling the cluttered grounds of his small corner house in chaps, boots, and cowboy hat. Sometimes, when he’d had a few, he’d dispense with clothing altogether and ride naked through the darkened streets on his motorcycle.

But amid the drinking stories and reminiscences, I posted constant reminders of present-day Flint’s condition. In Flint, autoworkers are often referred to as shop rats—sometimes affectionately, sometimes not—so it’s fitting that a chain restaurant symbolized by a big, bucktoothed animatronic rat named Chuck E. Cheese served as one of the most high-profile examples of Flint’s decline.

On a cold Saturday night in January 2008, a grandmother named Margie was attending a birthday party for her five-year-old granddaughter at the pizza joint/video arcade where “a kid can be a kid” and adults can struggle to maintain their sanity amid the sensory overload. It’s located just outside the city limits in Flint Township on a road filled with big box stores, strip malls, and fast-food joints leading to the mall that helped kill downtown Flint in the seventies. Margie noticed more than a dozen teenage girls roaming the restaurant, probably bored with playing skeeball and crab grab and looking for trouble. A friend of Margie’s took offense when one of the girls bumped into her. Words were exchanged, followed by punches. Margie’s friend was quickly outnumbered. “There had to be twelve to fifteen girls on one girl,” she told the local press.

The family fun was just getting started. As many as eighty people were brawling when officers from seven different police departments converged on the restaurant. “The biggest thing we did was just try to control the crowd,” one cop said. “Once pepper has been sprayed, it’s floating in the air so we called in for medical help in clearing it. If people aren’t used to pepper spray, they get pretty scared and angry.” Those just might be the two most common emotions in Flint these days, but it’s not exactly what a grandmother has in mind when she plans a birthday party. “It was almost like a nightmare,” Margie said. “Kids were screaming. It was almost like we were in a stampede.” Police finally cleared the restaurant and shut it down for the night.

The next day, a local news crew arrived to film a segment about the brawl when another fight broke out in the parking lot. This one was minor by comparison—just ten people, all from the same family.

After initially downplaying the incident as a simple argument among friends, the Chuck E. Cheese corporate office responded by banning alcohol sales at the restaurant, along with profanity and gang colors. Less than a year later, the new policies appeared to be working, at least by local standards. The Flint Journal ran a feel-good story proclaiming that the restaurant was clearly a “more peaceful place” because cops had responded to only a dozen calls since the brawl, mainly for purse snatching and parking lot vandalism. “Nothing major,” the Flint Township police chief said. “No fights.”

I suppose the brawl was hardly the worst thing that ever happened in Flint. Nobody died, after all. Friends with kids have jokingly told me that visits to Chuck E. Cheese often propel them toward violence. But for me, it was a reminder that there were really no safe zones left in the Flint area. Weird shit could happen just about anywhere.

These depressing posts often prompted heartfelt laments from readers. “I moved from Flint five years ago to Seattle, Washington,” read one comment, echoing the theme of many others. “I did that because I saw my beloved hometown dying. At Christmas time I visited family and friends. I took what you might call the ‘Grand Tour’ of Flint. What I saw just made me want to cry. I can’t believe that Flint has gotten that bad. My family told me it was bad, but, wow, I didn’t think it could degenerate to the point it has. I truly am sickened by what has happened to Flint. Needless to say I felt like I was escaping when I got on my flight at Bishop Airport. I hope it turns around soon. I hope that city someday returns to its former glory.”

Many comments were deeply personal, and they often came from unexpected sources. Howard Bragman is a public relations guru in Los Angeles who has advised everyone from Stevie Wonder to Paula Abdul, as well as making appearances on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Larry King Live, and Good Morning America. He emailed me an excerpt for the blog from a book he had written describing his less than ideal years growing up in Flint. “I know what it’s like to be an outsider—I grew up a fat, Jewish, gay guy in Flint,” he wrote. “In Hollywood, those are the first three rungs up the ladder of success, but in a town like Flint, it’s three strikes and you’re out. It’s a little like that Twilight Zone episode with a whole planet full of deformed people and they make fun of the normal guy.”

My mom, pushing eighty and living in Florida, became a frequent contributor. Born in Flint in 1930, she grew up on Illinois Avenue, just around the corner from the house that would later become Gypsy Jack’s cowboy corral. She had the same love-hate relationship with the city that I detected in many other readers. She clearly related to the working-class mentality of the place and didn’t deny that she was a hell-raiser growing up, causing her parents no end of grief as she took full advantage of the bar culture Flint had to offer. She had no shortage of affectionate stories about her early life in the Vehicle City. Yet she didn’t hesitate to leave when she got the chance, heading to Wayne State University in Detroit before dropping out and moving to New York City to become a department store model in the fifties. She hung out with the jazz crowd at Birdland and Minton’s Playhouse. She drove with Charlie Parker to a gig in Philadelphia once. She fell in love with a saxophonist from Detroit. Then it was on to Miami, where she became a stewardess—she’s still opposed to the term “flight attendant”—for National Airlines, flying regularly to Havana and New Orleans. It was the scattered trajectory of a beautiful young woman searching for something in life that she couldn’t quite identify. After a short-lived marriage to a navy pilot—make that two short-lived marriages to two navy pilots—she returned to Flint, a divorced single mother with four kids. She threw herself into more mundane work in the admitting office at McLaren Hospital, supporting her family, paying for Catholic schools and expensive private colleges. Despite returning under tough circumstances, she never turned on Flint, even while acknowledging her ever-present desire to escape.

“I grew up on the East Side and recall the unexplained pride I felt when the 3:30 Buick factory whistle blew and the roughly dressed workers poured out of the General Motors labyrinth swinging their lunch pails. Some were headed for home and some for the corner bar, but all with the determined step of an army after a battle won. I somehow felt as if I were a part of this giant assembly line and the city it fed,” she wrote in one post. “Nostalgia, I’m sure, is the opiate of old age. Memories over ten years old automatically become the ‘good ol’ days.’ We remember only the happy things and leave the shaded areas behind. And yet, faintly sifting through the sands of time, I seem to recall saying, ‘The day I’m eighteen, I’m leaving this town.’”

As a newspaper and magazine writer wary of online journalism, I had to admit that the blog had succeeded in ways I never could have imagined. Before long, it racked up two hundred thousand unique visitors and six hundred thousand page views. Tiny numbers compared to big blogs, but who would have imagined that many people cared about Flint? More importantly, I felt more in tune with the city than I had in years, despite going back only a handful of times over the past three decades. I reconnected with old friends and made new ones. Flint was a part of my life again. When the Flint Journal called to write a story about Flint Expatriates, even though I frequently mocked the local rag, I blurted out “I love Flint” in the interview, which of course became the headline for the piece. Where had that come from?

Ben Hamper, my literary hero and author of Rivethead, wrote to tell me he enjoyed the blog and inadvertently gave me the answer. He lives in northern Michigan now but made frequent visits back to Flint. He managed to capture my simultaneous repulsion and affection for our hometown in a single line near the end of his email: “It’s a dismal cascade of drek, but it’s still home.”

Like a lot of people who hit midlife in an adopted city, I began to think of my hometown as a center of authenticity—my authenticity. It took a couple of years of blogging for me to realize it was a place where I knew every street, building, and landmark. A place where I still had a deep-rooted connection to people, even after all these years. No matter how long I live in San Francisco, I sense I’ll never know it like I know Flint.

My family had no direct connection to the auto industry. My mom logged one day at AC Spark Plug and called it quits. My distant father was a navy carrier pilot who had degrees from Annapolis and the Naval Postgraduate School. He drove a Mercedes he couldn’t afford, not a Buick. I’ve never changed the oil in my car by myself. But there’s no denying I’m a product of Flint culture, both high and low. There are things I still hate about it, but my identity is wrapped up in the place that Hamper called “the callus on the palm of the state shaped like a welder’s mitt.”

Even the smells that trigger my strongest emotional response snap me instantly back to Flint. One is the dry, papery odor of books, which reminds me of the long summer days I spent reading in the air-conditioned splendor of Flint’s well-stocked public libraries. The other is that pleasantly repulsive mixture of spilled beer and stale cigarette smoke, spiced with a delicate hint of Pine Sol and urinal cake, that you find in a certain kind of bar. It conjures memories of eating fish dinners as a kid in places like Jack Gilbert’s Wayside Inn, and the mysterious darkened interiors of taverns you could peer inside on hot days when the door was propped open, not to mention the various Flint bars my friends and I frequented in high school and college. It didn’t matter that I had lived in California longer than I lived in Flint. Flint was part of me, and I was part of Flint.