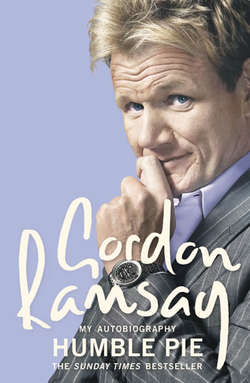

Читать книгу Humble Pie - Gordon Ramsay - Страница 9

CHAPTER THREE GETTING STARTED

ОглавлениеGROWING UP, THERE wasn’t a lot of money for food. But we never went hungry. Mum was a good, simple cook: ham hock soup, bread and butter pudding, and fish fingers, homemade chips and beans. We had one of those ancient chip pans with a mesh basket inside it, and oil that got changed about once a decade. I loved it that the chips were all different sizes. She used to do liver for Dad – that was the only thing I refused to eat – and tripe in milk and onions; the smell of it used to linger around the house for days and days. Steak was a rarity: sausages and chops were all we could afford. We were poor, and there was no getting away from it. Lunch was dinner, and dinner was tea, and the idea of having a starter, main course and pudding was unimaginable. Did people really do that? If we were shopping in the Barras, and we decided to have a fish supper, we children all had to share. There was no way we would each be allowed to order for ourselves. Later on, when Mum had a job in a little tea shop in Stratford, she’d bring home stuff that hadn’t been sold. We regarded these as the most unbelievable treats: steak-and-kidney pies and chocolate éclairs.

We were permanently on free school dinners. That was terrible. It used to make me cringe. In our first few years, of course, none of the other kids quite cottoned on to what those vouchers were about. But higher up the school it became fucking embarrassing. They’d tease you, try to kick the shit out of you. On the last Friday of every month, the staff made a point of calling out your name to give you the next month’s tickets. That was hell. It was pretty much confirmation that you were one of the poorest kids in the class. If they’d tattooed this information on your forehead, it couldn’t have been any clearer. So yes, I did associate plentiful food with good times, with status. But I’d be lying if I said I was interested in cooking. As a boy, it was just another chore. My career came about pretty much by mistake.

I latched on to the idea of catering college because my options were limited, to say the least. I didn’t know if the football would work out. I looked at the Navy and at the Police, but I didn’t have enough O levels to join either of them. As for the Marines, my little brother, Ronnie, was joining the Army, and I couldn’t face the idea of competing with him. So I ended up enrolling on a foundation year in catering at a local college, sponsored by the Rotarians. It was an accident, a complete accident. Did I dream of being a Michelin-starred chef? Did I fuck! The very first thing I learned to do? A bechamel sauce. You got your onion, and you studded it with cloves. Then you got your bay leaves. Then you melted your butter and added some flour to it to make a roux. And no, I don’t bloody make it that way any more. I remember coming home and showing Diane how to chop an onion really finely. I had my own wallet of knives, a kind that came with plastic banana-yellow handles. At Royal Hospital Road, we wouldn’t even use those to clean the shit off a non-stick pan, let alone chop with them. But we were so proud of them – and of our chef’s whites. I treated my knives and my whites with exactly the same love and reverence as I used to my football boots. I sent a picture of me in my big, white chef’s hat up to Mum in Glasgow. I think she still has it. I was so fucking proud.

Meanwhile, I had a couple of weekend jobs. The first was in a curry house in Stratford – washing up. The kitchen there wasn’t the cleanest place in the world, and they worked me into the ground. Then, in Banbury, Diane got me a job working in the hotel where she was a waitress. Again, I was only washing up, but that was when I first got the idea of becoming a chef. I was in the kitchen, listening to all the noise, and I was fascinated. I couldn’t believe the way people were shouting at each other. I was working like a fucking donkey, but the time used to fly by. I was enraptured.

After a year, one of my tutors suggested to me that I start working full-time, and attend college only on a day-release basis. I’d made good progress. That said, I was by no means the best kid in the class. In college, you can spot the students from the council estate, the ones who are basically middle-class, and the ones whose parents are so in love with their daughters that they send them to cookery school. God knows why. There are three tiers, and you can spot them a mile off. I was in the first group. I didn’t get distinctions, and I wasn’t Student of the Year. But I did keep my head down, and I did work my bollocks off. I pushed myself beyond belief. I was happy to learn the basics. I didn’t find it demeaning at all.

So I started work as a commis at the place where I’d been washing up: the Roxburgh House Hotel. The dining room was pink – pink walls, pink linen – all the waiters were French and Italian and all the cooks were English. My first chef was this twenty-stone, bald guy called Andy Rogers. He was an absolute shire horse. The kind of guy who would tell you off without ever explaining why. Dear God, the kind of food that he encouraged us to turn out. I shudder to think of it. The cooking was shocking, the menus hilarious. Take the roast potatoes. They started off in the deep fat fryer and then they were sprinkled with Bisto granules before they went in the oven, to make sure they were nice and brown. Extraordinary. The foie gras was all tinned.

We used to serve mushrooms stuffed with Camembert. One of the dishes was called a scallop of veal cordon bleu. It was basically a piece of battered veal wrapped around a ball of grated Gruyère in ham. I knew it was all atrocious, even then. I was getting all this information at college, and I would come back and try to apply it. I’d say: ‘You know there’s a short cut. To make fish stock you should only cook it for twenty minutes, otherwise it will get cloudy, and then you should let it rest before you pass it through a sieve, or it will go cloudy again.’ For this, I would get roundly bollocked by the chef. He didn’t give a fuck for college.

I stayed for about six months, and then I got a job at a really good place called the Wickham Arms, in a small village in Oxfordshire. The owners were Paul and Jackie, and the idea was that I would live above the shop, which was a beautiful thatched cottage. Unfortunately, things went pear-shaped there pretty early on. Jackie was in her thirties, I must have been about nineteen, Paul was away a lot; perhaps you can imagine what was going to happen.

Paul was mad about golf, and he loved his real ale. So he’d be off down to Cornwall, in search of these wonderful kegs. I had a serious girlfriend at the time, I’d met her at the college but she was going off to university. So that didn’t stop me. Basically, I was in charge of the kitchen, and a 60-seat dining room, and I wasn’t even properly qualified yet. I was making dishes like jugged hare and venison casserole and doing these amazing pâtés, and just reading endless numbers of cookery books. Locally, everyone loved the food, and it became a kind of hot spot. But I guess that went to my head: I was on my own, completely free, no one checking up on me. I was all over the fucking shop.

One day, while Paul was off on one of his trips, Jackie rang down to the kitchen. ‘Can I have something to eat?’ she said.

‘What would you like?’

‘Just bring me a simple salad, thanks.’

So I got together a salad with a little poached salmon and took it up.

‘Jackie, your dinner is ready.’

And she opened the door – stark bollock naked. I put the tray down, and went straight into her bedroom.

For the next six months, I led a kind of double life. There was Jackie, my teacher, and Helen, my pupil. You know what it’s like when you’re young. It’s awkward and clumsy. Sometimes, at least before I met Jackie, I used to feel that sex was like sharpening a pencil. You stick it in there, and grind it around. But Jackie was teaching me all these things, and it was amazing. The trouble was that Helen got some of the fringe benefits, which meant that she was falling more and more in love with me.

At first, Paul would only be away for a couple of days at a time. Then he started going on golfing trips to Spain for more like a week. That’s when it all got too much. It was getting heavy. Fucking heavy. Jackie told me that she loved me. The truth is that I loved making the jugged hare more than I did having sex with the boss’s wife, but the only reason I was in a position to buy and cook exactly what I wanted was precisely because I was shagging her. Things weren’t exactly going to plan and it was all getting too nerve-racking for me: that he might notice, that we might get caught, the fact that she was always telling me she was in love with me. So I told them that I was leaving to go and work in London. She went bananas.

I actually went back to the Wickham Arms two years later, for a mate’s twenty-first. Someone must have told Paul because, while she was still being very flirtatious, he was clearly not too pleased to see me. I was in the kitchen, talking to the new chef, telling him how good I thought the buffet was. There was a carrot cake sitting there and, without thinking, I stuck my finger in it. Well, one of the waitresses must have snitched on me to Paul because a split second later, he came running in and shoved me hard against the wall.

‘I should have fucking done this three years ago,’ he said. ‘You know what the fuck I’m on about.’

He then took a swing at me, but fortunately one of my mates intervened, which gave me enough time to make a very sharp exit. So I ran from the kitchen, jumped in the car and disappeared into the night. Hilarious. The next time I saw them was quite a long time later, when they turned up at Aubergine in the early part of 1998. They’d opened a new restaurant in a village in Buckinghamshire, and they brought their chef to meet me at Aubergine. By then, a lot of water had passed under the bridge. They had rung me, told me that he was a big fan of mine, and asked if they could come by. I said, sure, of course. It was embarrassing – I mean, I’d moved on, I wasn’t just poaching salmon and chopping aspic any more – but I made out it was good to see them all. The trouble was, they got pissed and a bit leery and then, when they missed the train back to Buckinghamshire, they started demanding that I offer them a bed for the night. We did try to ring around and find them a room, but hotels were £250 per night, which seem to make them even more aggrieved. I don’t know what they expected me to do – ask them back to sleep on the floor of my flat as well as cook their food? Well, I wasn’t having that. Tana was pregnant at the time, so I sent out their dessert and then I fucked off.

At half-past one in the morning, I got a call from Jean-Claude, my maître d’. He was screaming at me down the telephone. This chef of theirs was holding him over the bar, demanding that the arrogant fucker who left without saying goodbye – i.e. me – come on the line. About fifty minutes later, I rocked up on my motorbike. I thought I better had, and I was right. It was total mayhem. There was Mark, my head chef, fighting with Paul, and Paul’s new chef fighting with Jean-Claude. Naturally, I just could not stand by and watch Aubergine get trashed or my staff take a beating. But they both moved towards me before I had time to think. Paul was going: ‘I trusted you. How dare you – you shagged my wife!’ All my staff were thinking: WHAT? I could see it on their faces. The resulting mêlée caused major headlines when the Old Bill arrived because there was so much blood everywhere. We all got taken off to make statements and then, when the whole thing was written up in the London Evening Standard, predictably, it was me who was supposed to have thrown all of the punches. It was all: ‘I came to meet the great master and instead found an arrogant bastard’, ‘Brawl that wasn’t on the menu’ and ‘Ramsay punched my husband in the mouth’. That kind of rubbish. I had to take legal action to clear that one up. I kept my powder dry until all the other papers had followed suit and then I issued proceedings. I won, of course. As for Paul, he sobered up pretty fast once he got back to Buckinghamshire. He sent me a fax apologising. That was the end of that.

To be fair, they really looked after me, those two. Before it all went wrong. I mean, I wasn’t exactly as sweet as pie. Of course I wasn’t Mr Innocent. I was a little fucker, actually – no mum and dad around, a place to live, a girlfriend, thinking I was the dog’s bollocks. I would borrow my girlfriend’s father’s car all the time, even though I hadn’t passed my test. I used to leave the kitchen at half-past one in the morning and drive down the country lanes, over to Helen’s. One night, I left the pub in this car, and turned a corner only to be met by two sets of headlights: one car overtaking another on a bend. I pulled out of the way, but they hit the back of my car and it went into a spin, straight into the very prettily beamed sitting room of the nearest cottage. My head was cut, my knees were cut and all I wanted to do was to make myself scarce as quickly as possible because, of course, I shouldn’t have been driving at all. My test was still five weeks away. So that’s what I did – I absconded. Unfortunately, the police picked me up three hours later, hiding out in some fucking manure dump.

Naturally, I was prosecuted. As it turned out, the case came up the day after I was due to take my test. My solicitor told me that he strongly advised me to pass it because it would help my case in court, but I failed and so, in the end, I was banned for a year even though officially I wasn’t actually able to drive. I was also fined £400. About five years ago, I got a solicitor’s letter from the new owners of the cottage I’d smashed up; they were still trying to claim the £27,000 worth of damage I caused. Pass the place today and, in the spot where I made my unannounced house call, you can see that the bricks are still two different colours. Yes, I might have been an extremely ambitious young man, but I was also a bit of a tearaway. I can’t deny it. I don’t really blame Paul for wanting to beat me up. Any man would have done the same in his position.

So, to the starry lights of London. I was second commis, grade two, at the Mayfair Hotel, in its new banqueting rooms, as planned. I stayed about sixteen months, and I learned a lot. I used to make the most amazing sandwiches, the smoked salmon sliced incredibly thinly, because I had to do room service as well. On my day off, I would work overtime without getting paid, just for the chance to work in what we used to call the Château – the hotel’s fine-dining restaurant, where all the staff was French. If you fucked up during service, you had to work in the hotel coffee shop. That was the punishment. It was a tough place. If someone called in sick, you could easily end up working a twenty-four-hour shift. You’d work all day in the restaurant, and then during the night you’d man the grill and do the room service. At half-past four in the morning, all the Indian kitchen boys would sit down and have their supper, and then they’d go and pray for an hour, and you’d already be doing prep for the next morning’s breakfast. In those days, a hotel’s scrambled eggs were done in a bain-marie. You whipped up three trays of eggs and then you put them, along with some cream and seasoning, into the bain-marie so it could cook slowly, over a period of two and a half hours, at the end of which it was like fucking rubber.

Naturally, like a true goody two-shoes, I said: ‘Look, I’m on breakfasts this morning. I’m going to make all the scrambled eggs to order, chef.’ And that’s exactly what I did, though I got fucked when I came back from my day off because there’d been so many complaints about how slow the breakfasts had been. ‘But chef,’ I said. ‘I may have been a bit slow, but at least they weren’t rubber eggs. They were freshly made to order.’ He wasn’t having any of it. ‘I don’t give a fuck,’ he said. ‘We had to knock about twenty-five breakfasts off bills.’ I got such a bollocking – a written warning, in fact. But when he gave it to me, in a funny way, it was helpful. It was there in black and white that I was working in a place that wasn’t for me – a place where you got a warning for failing to cook crap scrambled eggs. I knew I had to get out.

In those days, there was a really cool restaurant called Maxine de Paris, just off Leicester Square, and I’d heard that they were opening a new restaurant in Soho called Braganza. So I got a job there as a sort of third commis chef, though I didn’t stay long because all the food went in a dumb waiter, rather than being picked up straight off the pass by a human being, which meant it was always a bit cold, and I just couldn’t come to terms with that. But there was an amazing sous chef there called Martin Dickinson – now the head chef at J. Sheekey – who’d worked at a restaurant called Waltons in Walton Street, a Michelin-starred place, and he was just phenomenal. I suppose that’s when I started thinking that Michelin stars were the Holy Grail, and that I wanted to work in a serious restaurant. Because Martin seemed like a God to me.

‘Get yourself into a decent kitchen,’ he told me. ‘This place isn’t for you. Trust me, you don’t want to be working in a place that serves smoked chicken and papaya salad. Get the fuck out of here.’

I would have worked it out somewhere down the line, but I owe it to Martin that I moved so quickly. I went up to the staff canteen, which was just a grotty little room, really, where all the chefs would smoke, and I grabbed a magazine and I took it out into the garden in Soho Square. ‘Christ,’ I said to myself. ‘There’s Jesus.’ Because on its cover was a photograph of Marco Pierre White, all long hair and bruised-looking eyes. I was nineteen. He was twenty-five. He’d come from a council estate in Leeds and then, when I looked at who he’d worked with and where…Nico Ladenis, Raymond Blanc, La Tante Claire and Le Gavroche. I thought: fuck me, he’s worked for all the best chefs in Britain. I want to go and work with him.

I phoned him up then and there.

‘Where are you working now?’ he said. So I told him.

‘Well, it must be a fucking shit hole because Alastair Little is the only place that I know in Soho, and if you’re not working there then don’t bother coming.’

I wasn’t sure what to say to that, so I told him, without even really thinking about it, that I was about to go to France because I wanted to learn how to cook properly.

‘Have you got a job out there?’ he asked.

‘No, not yet.’

‘Then come and see me tomorrow morning.’

I left the phone box and went back to the restaurant. I couldn’t stop thinking about what he’d said.

I turned up at what would become the legendary Harvey’s the following day, as requested. We’re talking about the earliest days of the restaurant. It had only been open about six months, and it would be another six months before it got its first Michelin star.

I suppose I expected to walk in and see him sitting at a table writing menus or something. Not a bit of it. I walked into this dingy alleyway, and said to a guy who was standing there: ‘Can I speak to Marco?’ The guy turned round and looked at me. It was him.

‘Are you Gordon?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Stand there.’

I did as I was told. I just stood there for about twenty minutes while he boned pigs’ trotters. I didn’t know what to think. Part of me wanted to go ‘fuck this’ and walk out, but another part of me was so fascinated by what he was doing that I stopped noticing how much time had passed.

Finally, he took me through to the dining room there, sat me down and gave me a coffee.

‘Look,’ he said. ‘We work so fucking hard here. This kitchen will be your life. There’s no social life, no girlfriends, and it’s shit money. Do you want to leave now?’

‘No, no. Not at all.’

So that was it. Next thing, he’s telling me to get changed and come into the kitchen. He was making pasta. I’d never made pasta in my life. He showed me how to do a ravioli, he showed me how to do a tortellini, then I had a go.

‘Those aren’t going on the menu,’ he said. ‘They aren’t perfect. But things are moving pretty quickly here.’

I was scared of fucking up. But it was almost like doing an assault course. No matter what happened, you had to finish that fucking course. So even if I was clumsy, I was determined to get there in the end.

‘Your fingers move fast,’ he said. ‘Do you want a job?’

‘Yeah, I’d love a job.’

‘You start Monday.’

But Monday was going to be a problem. ‘I’ve got to give a month’s notice,’ I said.

‘Well, if you really want the job that fucking badly, you start Monday.’

I was shitting myself, but there was nothing for it: later on that day I phoned him and told him that the people at Braganza were refusing to pay me that month’s salary unless I worked my notice.

‘I’ve got this to pay and that to pay,’ I said. ‘I’m going to have to stay put.’

‘What hours are you working?’

‘I’m on earlies for the next month.’

Problem solved. I did the early shift at Braganza from 7 a.m. until 4 p.m., and then I got the tube to Victoria, and the train from there to Wandsworth Common, where I’d work at Harvey’s until about two o’clock the following morning. I kept this up for the whole month. I had no choice. It turned out that Marco’s warning about the restaurant taking over my life was only the half of it.

In the beginning, I admired Marco more than I can say. I wasn’t in love with the mythology – you know, this screwed-up boy who’d lost his mother at six and had been dedicating dishes to her memory ever since – but his cooking left me speechless: the lightness, the control, the fact that everything was made to order. In the kitchen, there’d be six portions of beef, or sea bass, or tagliatelle, not fifty. Everything was so fresh, everything was made to order.

There was one dish I particularly admired – Marco’s tagliatelle of oysters with caviar. In his most famous book, White Heat, he spouted all kinds of shit about that dish, about how it was his first ‘perfect flower’, how some chefs spend a lifetime looking for a dish like that. Bollocks. Still, I do believe that it will go down as a classic. The oysters had been poached in their own juices; the shells had twirls of tagliatelle in, and the oysters on top of that, and some wonderful thin strips of cucumber that had been poached in oyster juice, all topped with caviar. It was elegant, delicious and simple. It was extraordinary. Not that I ever got to eat it. We tasted, tasted, tasted, but we never actually ate. I never saw Marco sit down and eat. Never.

It was as if I was putting on my first pair of football boots all over again. I felt very low on the ladder. Speed-wise, I was fine; my knife skills were great. But everything else I’d learned, I’d had to forget fast. Everything we produced had such great integrity: it was clean, honest food, and it tasted phenomenal. You’d taste a sauce ten, maybe fifteen times for a single portion. Then you’d start all over again when the next table’s order came in. One portion, one sauce.

But it was the toughest place to work that you could imagine. You had to push yourself to the limit every day and every night. You had to learn to take a lot of shit, and to bite your lip and work even harder when that happened. A lot of the boys couldn’t take the pace. They fell by the wayside. When that happened, you felt that you had been able to survive what they hadn’t.

Marco was running a dictatorship: his word, and his word alone, was all that mattered. He fancied himself as a kind of Mafioso, dark and brooding and fucking terrifying. He had favourites, and then they would be out in the cold. He would praise you, and then he would knock you down. He would abuse you mentally and physically. He would appear when you were least expecting him, silently. His mood swings were unbelievable. One minute, he was all smiles, ruffling your hair, practically pinching your cheek. The next he was throwing a pan across the kitchen. Often, the pan would be full. Stock everywhere, or boiling water, or soup. But you wouldn’t say anything. You’d wait for the quiet after the storm, and then you’d clear up, no questions asked. Marco was never in the wrong. If you didn’t like that, you were more than welcome to walk out of the door and take a job in some other restaurant. But he knew, and we knew, that there wasn’t anywhere like Harvey’s. There were better kitchens, with more stars and older reputations, but this place was something different. We were a tiny, young team, and we were blazing a trail. White Heat, with its arty black-and-white photos and its breathless fucking commentary, was well named.

The first time I saw Marco pummel a guy, I just stood there, my jaw swinging. It was a guy called Jason Everett. He got bollocked and I didn’t know where to look. I mean it. He was physically beaten, on the floor. Another time, Egon Ronay was in the restaurant, and we had this veal dish on the menu. Well, Jason had overcooked all the kidneys. So Marco went bananas. ‘Okay, Marco,’ Jason said. ‘I fucked the kidneys. I’ll go and apologise to Egon Ronay. I’ll go out there and apologise. Let me go. I’ve had enough.’ He went out into the alleyway outside the restaurant and that’s when Marco said: ‘Those chef whites, those trousers, that’s my fucking linen. You fucking take them off and walk round in your underpants.’ So that’s what the poor bastard did. He ripped off his whites and his trousers and he was bawling his eyes out, and then he had to walk past the front of the restaurant half naked.

We were all young and insecure, and he played on that. A lot of us were guys with a lot of baggage. He’d find out about your home life while you stood there peeling your asparagus or your baby potatoes. Then, four hours later, when you were in the middle of service and you’d screwed up, he would say: ‘I fucking told you that you were a shit cook. You can’t fucking roast a pigeon because you’re too busy worrying about your mum and dad’s divorce.’ One time he turned round and said to me: ‘You know the best thing that’s happened to you, Ramsay? The shit that ran down your mother’s leg when you were born.’ But if you answered back, you only made things worse. Best just to get on with boning the trotters, or whatever. Once, he was telling us all some outlandish story about jumping off a train. Everyone was laughing. But then I said: ‘Bullshit.’ He picked up his knife, then he threw it down, then he grabbed me and put me up against the wall. It was almost like being back at home with Dad. Maybe that’s how I was able to put up with it for so long.

Another classic occasion was when Stephen Terry, another of the chefs, attended his grandfather’s funeral and made the mistake of going to the wake afterwards. When he got back a bit late, Marco said: ‘I told you that you could go to the fucking funeral but that you couldn’t go for tea and biscuits. I want you back in the fucking kitchen.’ Steve was really crying. We were making tagliatelle that day, and Marco was shouting: ‘Come on Steve, fucking turn it, fucking turn it, you cunt.’ So he said: ‘Yes, Marco, I’m fucking on my way.’ That was it. Crash. Marco slapped him in the face.

‘That’s it,’ he said. ‘Get out of here. You may as well fuck off underground and join your granddad.’

After Jason Everett had left, we were all in the shit. Working at Harvey’s was physically exhausting anyway. On Sundays, you would sleep all day. But once we were a man down, no one got any breaks at all. Then one day Marco called me upstairs to the office.

‘I want you to do something for me,’ he said. ‘Jason is living in your flat, isn’t he?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, I’ve sacked him – and yet he’s still in my kitchen.’

I had no idea what he meant.

‘I mean that he’s sleeping in your house, and you’re working for me. When you come into work in the morning, you’ve slept under the same roof. I want you to go home tonight and kick him out. I want you to put his clothes, and all his knives, and any chef whites out on the street.’

I told Marco that I couldn’t do this. I loved my job, but I couldn’t do as he asked. ‘Are you going to sack me?’ I asked.

‘Sit there,’ he said. The next thing I knew, he was on the phone. He rings some restaurant, and says: ‘Hi John, it’s Marco here. Look, I’m in the shit. My sous chef (that was me) is being fucking awkward.’

I couldn’t believe it. Awkward? After all the work I’d done?

‘So John, three cooks next Monday.’ Then he put down the phone and said to me: ‘You’re leaving. You’ll leave in a week’s time. I want your notice.’

I went back downstairs. ‘Everything okay?’ said the guys.

‘Yeah.’

I started making ravioli, because by then I was completely running the kitchen. I finished the first one and then something in me just snapped: I hurled it at the wall. Fuck this, I thought. I walked out and I went to the train station opposite, where I tore off my whites and threw them in the nearest bin. I went back to the flat in Clapham.

‘What are you doing here?’ asked Jason. ‘It’s only six o’clock.’

‘Get changed, mate – we’re going out to party. Marco’s asked me to kick you out and I can’t do that. He’s told me I’m going in a week’s time. Why should I wait a week?’

Fifteen minutes later, we’re just getting changed when suddenly Steve Terry and another chef, Tim Hughes, and all the French waiters come in. ‘Marco’s closed the restaurant because you walked out,’ says Steve. I couldn’t believe it. The restaurant manager had to ring all the customers to make excuses for Marco closing the restaurant.

It was a Saturday night. We NEVER had a Saturday night off. So we went to the Hammersmith Palais and we got absolutely mullered. The next night, we all piled off to a pub called the Sussex. All the chefs in London used to congregate at the Sussex on a Sunday. It was about nine o’clock. I was a bit tipsy when all of a sudden the music stopped and someone shouted: ‘Is there a Gordon Ramsay in here?’ There was a phone call for me behind the bar. When I took it, a voice said: ‘Gordon. Marco.’ I mouthed his name to all my mates and they all started shouting abuse.

‘It’s clear that you’re with your mates,’ he said. ‘But I think we should talk.’

I told him that I had booked a holiday: I was off to Tenerife the next day.

‘What are you going to that shit hole for?’

‘Marco, after what you did to Jason and what you did to me, to be honest I can’t take it any more. You’ve pushed me to my limit. I’ve got to go.’

But he was insistent; he needed to speak to me, and I gave in. Why? The truth is that, in spite of everything, he was a strong influence on me. I’d confided in him. The abuse I’d had from Dad had no point. But with Marco, the more he screwed you, the more he turned you over, the more you felt yourself becoming better. It sounds crazy, but I was becoming grateful for the bollockings. My saving grace was that I could take it physically, even when it was like SAS training camp.

We arranged that I would meet him at Harvey’s at midnight.