Читать книгу The Bassett Women - Grace McClure - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

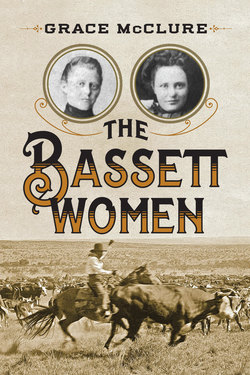

In the towns along the tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad in southern Wyoming, and down in the cattle country in Colorado and Utah, the locals still tell stories about the Bassetts. And when they do, they are talking about the Bassett women, those unorthodox and controversial Bassett women, compared to whom the Bassett men are almost shadows.

There were three of these women: the original pioneer, Elizabeth, and her two daughters, Josie and Ann. Elizabeth Bassett is remembered as “head of the Bassett gang.” Ann was first called “Queen of the Cattle Rustlers” by a Denver newspaper reporter, and she was known as “Queen Ann” forever after, partly because of her notoriety but also because her imperious ways and her regal bearing made the name a fitting one. The other daughter, Josie, gained her notoriety another way: in a time when divorce was almost unheard of among decent people, she acquired and discarded five husbands, at least one of whom she was suspected of killing. Still, Josie might now be forgotten except that, when almost forty years old, she piled her possessions into a wagon with a spare horse tied to its tailgate and left her childhood home in Brown’s Park to establish a homestead of her own. She found that homestead near Jensen, Utah, only forty miles away as the crow flies, but actually in almost another land because of the ruggedness and wildness of the intervening mountains. Josie lived there until her death almost fifty years later. As those years passed, she acquired the respectability of age (despite the stories still told about her) through the sheer strength of her personality, her generosity, her unaffected sense of humor, her companionability, and her stubborn insistence on living the way she wanted to. In her very old age she was as much a legend to the people of her countryside as was her sister Ann.

The Bassetts were early pioneers in a section of northwestern Colorado belonging topographically to the Wyoming Basin, a high arid land of broad plains, undulating hills and occasional outcroppings of rock. This vast, irregular bowl is bordered by high mountain ranges with snowy peaks and thick pine forests; within its boundaries it is divided again and again by lower ranges of bare brown mountains only occasionally relieved by the stunted cedars which grow in country where water is scarce. There is infinite variety in this land of canyons, mesas, ridges, peaks and mountains; there is also infinite monotony in the coloration of its brown grasses, dusty green sagebrush and sober-toned rock. It is magnificently and grimly beautiful. In its bareness and brownness the skeleton of the earth seems revealed.

The Wyoming Basin was the last frontier in “cattle country,” which extended as far south as Texas and as far east as Kansas and the Dakotas. In the late 1870s when the Bassetts arrived, the land west of the Rockies in Colorado was still reserved for the Ute Indians, and they lived there comparatively undisturbed by the white invaders. Their displacement was inevitable, of course, once the railroad linking the continent was built. The Utes fought their last battle in 1879.

Even before 1879, and well into the twentieth century, the white invaders were fighting among themselves. They were divided into two groups: the large cattle barons, who dominated those endless square miles of grassland by the sheer size of their herds, and the small ranchers, who sought to establish and maintain smaller herds in the lands immediately surrounding their homesteads. All these cattlemen, large and small, broke the laws of more settled communities because laws had not been written to fit the circumstances under which both groups fought for survival. In and among these “honest” lawbreakers, another group inhabited that vast country—the outlaws, the “professional” lawbreakers, who committed their crimes almost with impunity because the law was represented only in a scattering of barely emerging towns.

By happenstance, the Bassetts settled in the only valley in northwestern Colorado that could assure them a place in the folklore of the region. They filed their homestead claim in Brown’s Park, then known as Brown’s Hole, a small valley only thirty-five miles long and roughly six miles wide, surrounded by mountains so rugged that only from the east was there easy access. Not far from this eastern entrance was a little area called Powder Springs, a wellfrequented stopping place for outlaws on the run. But Powder Springs was overshadowed by Brown’s Park, which would become known as one of the way stations on a fabled outlaw trail that stretched from Hole-in-the-Wall in Wyoming to the north to Robbers’ Roost in Utah to the south. All three of these spots were in country well removed from the towns being established along the Union Pacific railroad, but of the three, Brown’s Park had a particular advantage. It straddled the borders of Utah and Colorado and was only a few miles from the Wyoming line. Thus, if by some unlikely chance a posse from one of the settled areas ventured into the wilderness in pursuit of a badman, in Brown’s Park that badman could simply ride across the border into another state and thumb his nose at his pursuers.

In this rustlers’ hangout, surrounded by warring cattlemen, the Bassetts lived in a world of rustling and thievery, of lynching and other forms of murder. Their neighbors could comprise the standard cast of a Hollywood western: honest ranchers, rough and tough cowboys, worthless drifters, dastardly villains, sneaking rustlers, gentlemanly bank robbers, desperate outlaws, and ruthless cattle barons. Most Americans assume this world vanished long ago, yet people alive today remember Queen Ann striding along in her custom-made boots and Josie riding to town for supplies with her team and wagon.

Ann died in 1956 when the Korean War was already part of history. When Josie followed her in 1964, the race to put a man on the moon had already begun. Both women were raised in a wilderness but lived to see an atomic, electronic world. Both women brought to that new world a combination of pioneer values and an utter disregard for any conventions that ran counter to their own standards of right and wrong. They were sometimes condemned by their more conservative contemporaries—understandably so, for what they did was not always admirable. They lived their lives as they wished, doing what they wanted to do or what they felt they were compelled to do, with never a serious qualm when they overstepped the bonds of “proper” society.

Since the day when the Pilgrims first stepped on Plymouth Rock, an independent woman has been no rarity in a country which always had a new frontier. Courage, resourcefulness and strength of will were necessities in wilderness communities, and people who possessed these qualities were valued and respected regardless of their sex. It is not surprising that the first crack in the wall of political discrimination against women appeared in frontier Wyoming, where in 1869 the territorial legislature gave women the right to vote in territorial elections. When those Wyoming women went to the polling booths, they were the first women in the United States—even the first in all the world-to cast ballots.

Elizabeth and her daughters were not active feminists; rather, they were pupils of the feminists who had prepared the way for them. And they were apt pupils. They were unusually independent and exceptionally autonomous, for even on the Wyoming frontier the typical woman was a follower of her man, not his leader. If the Bassett women seem forerunners of the feminists of the 1980s, it is because they were indeed in advance of their times in seizing the freedom which the frontier offered. Even so, their story would not be worth the telling if it were not for their personal qualities—audacity and strong will, high temper and obstinacy, good humor and open-handedness, unashamed sexuality—qualities that their contemporaries summed up as “the Bassett charm.”

Josie’s cabin still stands and can be seen today in Dinosaur National Monument in northeastern Utah. When the old lady died, the National Park Service bought the five acres she still owned and added them to its three hundred square miles of mountains and barely accessible canyons carved out by the Green and Yampa Rivers. The homestead is on the fringe of this wilderness, as is the Monument’s museum, a huge, greenhouselike structure covering the remnants of the vast cache of dinosaur bones which gave the Monument its name.

Twice a day the Park Service loads tourists onto a large open-sided bus and takes them out along the Green River, past the red sandstone bluffs with their pictographs left by long-gone Indian tribes, and down across Cub Creek to Josie’s homestead.

While the tourists are still on the bus, the Ranger uses his loudspeaker to tell them the legend of Josie Morris. “She was raised in an outlaws’ hangout . . . Some people say that Butch Cassidy was one of her sweethearts . . . . She was married five times, and there’s a story that she took a shot at one of her husbands but she denied it—she said that if she had been the one to shoot him she wouldn’t have missed. . . . Perhaps she got tired of men, for she came here when she was almost forty years old and lived out here—alone—for fifty years, with no running water, no electricity, no telephone. A real pioneer.”

The outlines of a carefully laid out working ranch still show despite the years of disuse and the tangle of late-summer weeds. The Park Service has done little to preserve the place except to board up the cabin’s windows and put a plywood canopy over the roof to protect it from the heavy winter snows. Even so, it is obvious that this is no hermit’s shack, no squatter’s cabin.

Peering through the slits in the boarded-up windows, one sees a smallish, square living room with a good brick fireplace and the faded remnants of once-gay blue wallpaper. To one side of this main room is a kitchen, to the other are two small bedrooms. There are porches on two sides of the cabin. On one of these Josie used to sleep, even during the bitter winter months.

Outside, a log fence still bars the mouth of the box canyon where Josie penned her livestock, although the canyon itself is now a thicket of brush and young trees. In what was once her garden area, old fences sag from the weight of her grapevines turned wild. The orchard is a graveyard of gnarled, dying trees. Wild watercress grows in the damp soil near the spring which still fills the pond where Josie kept ducks and geese, before spilling into the meadows below. The chicken house and an old corral still stand, but the springhouse where she stored her butter and the sty where she kept “Miss Pig” can only be imagined.

The Park Service’s benign neglect has given a poignant authenticity to what remains of Josie’s homestead. The visitors walk and speak softly, as if from respect for the pervading quiet of the place, a quiet broken only by the gurgle of the spring water from an old iron pipe. One can imagine the loneliness of living in such a silent place and the serene strength of the woman who could endure that silence. The silence is provocative, raising questions that the Ranger’s rehearsed information does not answer, questions as to what kind of woman Josie really was and where she came from.

If the ghost of Josie Morris could be asked those questions, it is doubtful that she could provide answers, for Josie was always too busy to spend much time on idle introspection.

And if Queen Ann’s ghost were at Josie’s side, her answer might only raise more questions. “She was a Bassett! A Bassett of Brown’s Park!” To Ann, that would explain everything.