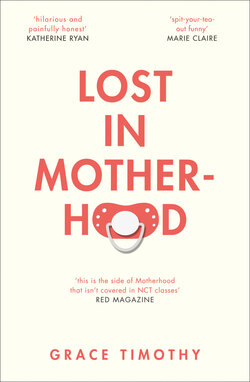

Читать книгу Lost in Motherhood - Grace Timothy - Страница 7

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеI attempt to sit still, to look as relaxed and open as possible, but I’m on one of those chairs that leans back on a bendy frame. You know the ones? That kind of plastic-looking blonde wood with a creamy-coloured leather cushion. I looked it up online after our session – it’s from IKEA (obviously) and it’s called ‘Poang’, which is Swedish for ‘point’. As in, what’s the point? I think people buy them as nursing chairs, too.

Well, I would have lost a nipple if I’d tried to breastfeed in this chair, let me tell you. My stomach muscles were shot to hell once I’d given birth and I’d have been about as steady on a rocking chair as a drunken eel. Plus, my vagina was so mashed up, the idea of grinding it back and forth on a beech veneer would have broken me for good. I definitely rocked in those early days, but it was more of the rocking-in-a-dark-corner type of move, deprived of sleep and a functioning pelvic floor. The sort you can do on completely immobile furniture or even the floor.

You have to be so cocky to make one of these chairs rock gently and comfortingly, and not throw you off like a spooked horse. I am not cocky or relaxed in this scenario, and have to slam my feet down suddenly to steady myself. I’m aware it’s made me look uneasy. One false move and you look like you can’t handle it. This chair is basically a metaphor for motherhood and the predicament I find myself in now.

I am sitting here in a stranger’s living room with no shoes or socks on. Bit weird. It’s OK, I’m actually here for a nice bit of reflexology, with a birthday voucher from my mum and I’m finally getting round to using it six months later, on the day it expires. ‘You deserve a bit of a treat, darling,’ she’d told me at the time, ‘You look a bit knackered.’ Weird way to kick me when I’m down, I think, smiling through clenched teeth at the thought of trying to fit in this so-called treat, and of the new electric toothbrush I’d hinted at for three weeks. But my mum volunteered to babysit and now here I am on Pat’s Poang, answering her questions about my medical history.

I’m an easy customer in this respect – no operations, no medications, no family history of diabetes. Uneventful pregnancy and straight-forward vaginal delivery. Couple of stitches, nothing to write home – or down on a form – about. I don’t have so much as a high blood pressure or a tennis elbow, so we whizz through the checklist. A nice little foot rub, I think to myself, Might be awkward when she finds the verruca I picked up at BabySwim, but otherwise, I’ll just sit here, relax, be serene … Then she says it:

‘And how about your emotional wellbeing, how are you feeling right now?’

I smile, a smile I plaster on my face, which should say I’m fine! But usually makes people take a step back and ask, ‘Are you sure?’ from a safe distance. It’s become my ‘mum face’ – the mask that covers up the underlying cocktail of anxiety and bewilderment which has been simmering since I gave birth nearly three years ago. But this time, it slips:

‘I would say … well, I am maybe a bit anxious. Well, a lot. And most of the time, too.’

‘Oh?’ She doesn’t seem surprised, ‘And why’s that?’

‘Mainly because I love my daughter so much I’m terrified I’ll lose her or fuck it all up for her. I don’t think I was ready to have kids and I have literally no idea what I’ll do when she starts nursery because I don’t know who I am anymore without her.’ This sounds much worse out loud than in my head and I think perhaps I’ve overdone it a bit. ‘I mean, don’t get me wrong, I love being a mum!’ Reel it back in. Don’t call the Social, don’t take her away! ‘But I find myself just bowling through the routine every day and then feel a bit joyless when she’s gone to bed. Like, what’s it all for? I mean, I really enjoy my job, but doing it makes me feel guilty, plus, I’m not sure I’m very good at it any more. Is she even having a nice time? I don’t have much of a social life anymore; I don’t really have many friends nearby. I don’t really know what to say half the time. I’ve also lost my sex drive,’ – I soundlessly mouth ‘sex drive’ rather than say it out loud – ‘my body, my name even …’ I pause – the massive digital clock on the wall flickers to 10.25 and breaks my flow. It’s a beautiful autumnal day and I catch a glimpse of golden leaves and rolling hills outside as the Roman blind is blown away from the window for a second. It feels good sharing like this out of my family’s earshot.

‘So you feel it’s changed you, Grace? Becoming a mother?’

One minute I was just me, doing my thing. I defined myself by my likes and dislikes, my desires, career and relationships. I did whatever I wanted to do. After years of body-image battles, I finally felt like the agent of my own body and I’d grown to understand how it worked. No matter how far I travelled or how my life changed slightly, the constant was the familiarity of my own self. But a cursory New Year’s shag before the takeaway curry arrived was enough to change my life forever. In that instant, I lost control of my body and mind as they were repurposed to grow a baby. My identity started to slide off me as hormones and then love infiltrated every thought and feeling. The colleagues, friends and even strangers who played a part in shaping and supporting my sense of self slipped away, work dwindled as every hour became a moment in my child’s life. I felt like I had to fight twice as hard to have a voice. My confidence was knocked by the constant feedback from everyone and their suffocating deluge of opinions and anecdotes. I tried to fit in everywhere – old life, new life – and didn’t fit in anywhere.

It doesn’t matter how you come to motherhood – biologically, by adoption or surrogacy – it changes everything. You are now a MUM. What I experienced is an identity crisis which no social group, age, creed or race is immune to. It’s something I’ve heard of in different forms from every mother I’ve ever met, an uncomfortable truth that belies the belief that being a mother is the most natural thing a woman could do. From the physical and emotional changes you encounter to the way your agenda and daily life is altered, your identity is constantly up for redefinition. ‘I thought I was patient,’ I would think to myself, ‘I thought I was bright …’ And you’re expected to shelve these concerns because you don’t matter anymore. Not compared to the baby, how you’re working to help shape her identity.

My coat is folded over my lap and my fingers are burrowing through the pocket where a thread has come loose. I tug at it, pushing my fingertips through the ragged seam into the lining. This coat is enough of an answer to this question. I find a small, plastic toy fish floating around. Found Nemo, didn’t I? That would obviously never have happened to me before I had a child. Nor would the crispy Wet Wipe I’m nudging aside. Nor the coat itself – a navy blue, knee-length puffa coat, waterproof, functional and covered in stains. You don’t have a coat like this unless you’re a mum or a shepherd.

In truth, I’m unrecognisable from the person I was just three or four years ago, before I got pregnant. If you’d told me back then that I’d be sitting here now deep in the Sussex countryside, wearing leggings that bag around the knees and pouring my heart out to a total stranger in a beige tunic, I would have called bullshit. Back then I was invincible and so sure of myself.

But here I am in this ugly chair, one finger now tangled in the lining of my mum-coat, mid identity crisis. I’ve lost sass and flirting, and about 65 per cent of my labia. I’ve lost perspective and 5,689 hours of sleep. I don’t stride or strut now; I hurry and chivvy, usually weighed down by my child, umpteen bags or a scooter. The responsibility is weighing heavy too, for this person I love so intensely – I am her advocate, I am her carer, and I have to get it right. But can I ever be good enough, be the parent she so deserves and I am in no way qualified to be? And where am I, where is the confident person I was before? I am now the wife who blackmails her husband for lie-ins, who criticises the way he looks at his phone when his child is asking him a question. I’m the woman who drives around for hours on end if it’ll help my kid nap, rather than face the screaming and ultimate failure of putting her in her cot and hoping for the best. I forget to turn up to things, I flake out on the nights out I used to live for, knowing the next day will be unbearable. I stand back from conversations with new people, no longer sure of how to introduce myself.

The simple bits of being a mum are obviously awesome – everyone knows how good it feels to hold your child, to laugh with them, to share their joy and see things afresh through their eyes. Even the more mundane bits can be an unexpected treat – it always surprises me how much I enjoy washing and drying her clothes, for example. I pick up the scrap of cardboard that holds the yoghurts together and tell my husband, ‘Ah, we’ll make something out of that’. I absolutely love being my child’s mother; nothing has made me happier, or could ever make me happier than being her mother. Nobody could love her more.

And this kid – she is the most amazing child. If I can’t excel at parenting this one, I’m seriously inadequate. She is incredible, the best thing ever. But the stuff is harder than anything I’ve ever endured. It’s hard sharing the experience and responsibility with someone else who may not always agree with you, the loss of sex and intimacy with that person, the onslaught of self-doubt. It’s hard to get through each day on so little sleep and then each night – hallucinating, nursing, arguing, worrying and begging for rest. I feel guilty when I’m not with her, guilty when I’m with her that I’m thinking about not being with her, or because we’re watching too much TV. I’m always tired, always.

I’ve been policing myself, too – cautioning myself not to become that kind of mum or that kind of woman. No sugar, no soft play, no iPad, no tacky plastic shit, no chemicals … but also, like, super-relaxed and laid-back. My ambitions have been compromised, of course they have, but what’s worse is that it bothers me. I’m also bad at work now, and when work’s going well, I’m bad at being a mum. And I’m scared every single day, scared she’ll die, that I’m doing it wrong, that I’m letting her down. I realise neither Pat nor I have said a word for a long time now.

‘Soooo, will we do the foot rubbing bit now?’ I ask eventually.

‘If you want to, but we can just talk if you’d like?’

Uh oh, sounds like Pat might be moonlighting as a therapist here, I think. Oh, I shouldn’t have said anything. When I’m not forthcoming, Pat places her pad down on the floor and reaches out to hold my hands in hers.

‘I think you really need to invest in some space for yourself,’ she goes on, ‘Have you tried meditating? Book 15 minutes out to meditate, another 15 for a walk outside, just you. And I think you’d really benefit from some body work too – regular sessions with me and maybe some cranial osteopathy. You need to make time for yourself, Grace.’

I consider this. ‘Do you have kids, Pat?’

‘No.’

‘Ah.’