Читать книгу The Sword of Eden - Gracia Grindal - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеThese sonnets on Eve and Mary have been a project of my last few years. Teaching Bible studies that focused on Eve and Mary made me more and more curious about them. While we know much less about Eve than Mary, neither woman has much to say. What they did say, however, has echoed down through Christian history. The church has meditated on them, written on them, painted them, included them in theological commentary and history; both have been characterized in popular and pious history: Eve is to be admired, despite her disobedience. Mary is to be admired for her obedience. Both suffer from cliché existences, Eve the temptress, Mary, impossibly good. Both are pivotal to the Christian faith. Eve is often blamed unmercifully, by especially the early Christian fathers, for bringing sin, and worst of all, sexuality, into the world, though some do admire her for her curiosity, and bravery in reaching out to taste of the forbidden fruit. On the other hand, Mary is seen as holy and beyond reproach. Luther deeply admired and valued Mary as the first Christian in some ways because she bore the Word of God in her body as all faithful Christians do.

The main scene in Eve’s life is her decision to heed the tempter’s voice and that she blamed him for her fall. We do know that she had three sons, but other than that we know nothing, except as a woman she had a husband, sons, and she watched them grow up. She suffered the sorrow of discovering Cain had killed Abel. Most of the rest of her life we can imagine as being like many women—being in love, mothering her children, raising Seth wondering if he was the promised Messiah, growing weary of her mate, suffering middle age, seeing her son fall in love and marrying, facing old age and death. In a way, her experiences are those of everywoman, something I wanted to explore in these poems.

About Mary we know more. I have used, with some additions, the traditional scenes called the Joys and Sorrows of Mary dear to Marian piety, putting my own Lutheran twist on them. I am most grateful to the book by my friend Lisbeth Smedegaard Andersen God’s Mother and Heaven’s Friend: Mary Pictures in History (Guds Moder og Himlens Veninde.) It has shaped much of my thinking about Mary. My take on Mary is obviously Protestant, but I do appreciate and have learned much from the reverence in which she is held by Roman Catholics and what they have thought about her. One can see evidence of their regard in the thousands of beautiful paintings of Mary which have been painted down through time.

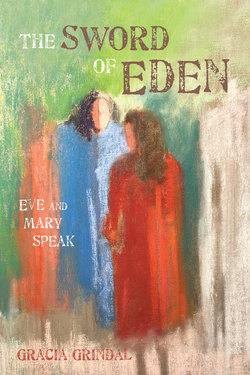

The Marian tradition is filled with conventions and understandings that one can see in any of the paintings. Mary is usually dressed in a blue cape over a red gown. Green foliage for life and white lilies for purity appear regularly in these scenes. She is usually reading a book when Gabriel approaches her. Tradition teaches that she was reading the prophecies of the Messiah. Elizabeth wears gold for her age. For the middle ages, colors, flowers and gems had a mystical language all their own, the meanings of which we have lost, but which are vital to the depictions of Mary. And which we can still read if we know this. Naturally, these many portrayals of Mary, with their brilliant and beautiful colors, were resources for me as were the gems used throughough the Bible as signs of heaven.

Generally, I used the Italian sonnet in the Eve sonnets, and the English for Mary. Both have been popular with English writers since the sixteenth century. Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, John Milton, John Keats, and William Wordsworth, and moderns like Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wiley, have left behind superb sonnets in traditional forms: Spenser, the tightest form with its rhyme scheme of abab bcbc cdcd ee, Shakespeare with his abab cdcd, efef gg now known as either the Shakespearean sonnet or English sonnet; John Milton perfected the Italian sonnet in English with its slightly more demanding rhyme scheme in the octet: abba cddc, and less so in the sestet, efgefg, efggfe, or some pattern like that. The English sonnet form is easier until the concluding couplet at the end which can easily degenerate into doggerel. All of their poems have what the tradition calls the turn, usually between the eighth and ninth lines, whch usually goes back and reflects on the first part, or raises the thinking into a higher plane. This is almost as natural as breathing in and out. The form demands the turn.

The music of the sonnet is to be found in its use of the iambic pentameter line, which is the basic line of English poetry. Fourteen lines, around 140 syllables give or take a few, are what Wordsworth called a “scanty plot of ground.” But as he concluded in one of his own sonnets “those who have felt too much liberty/have found brief solace there.” Unfortunately, too many contemporary poets have lost the subtleties of iambs, in the search for vivid surprises of thought, rather than in the music of well wrought poesy.

Thinking of the story of redemption from the point of view of either of these pivotal women has enriched my understanding of the Christian faith and helped me to feel more deeply the passion of Christ as his mother looked on. That has been a devotional experience that over the time has been enriching and powerful. It is my hope that these sonnets can cause pondering and wonder in my readers, as they have with me.

I am grateful to Lisbeth Smedegaard Andersen for her exploration of many of these themes in her book on Mary. Additionally, Alice Parker, long interested especially in Eve—her setting of Archibald MacLeish’s Eve poems were instructive as were her comments on both collections of my sonnets. Robert Schultz, Professor of English and Poet in Residence at Roanoke College, an old friend and student, helped greatly with the Eve sonnets. Tom Maakestad, the artist whose work graces the cover, continues to surprise with the accomplished beauty of his art. My gratitude to all four is filled with a deep satisfaction that knows no bounds. Most of all I must thank Jill Baumgaertner for reading the work and encouraging me to seek publication. She has been a friend to many a poet over time. For being a friend to me in this process, she has given my work a future, a future I had come not to expect. A poet should not say there are no words to express her gratitude. There are many, the best simply: Thank you.

Gracia Grindal

September 2017