Читать книгу Backpacker's Britain: Northern Scotland - Graham Uney - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

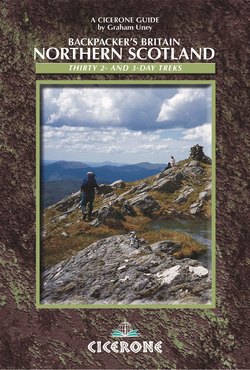

Hillwalkers crossing the moor beneath Suilven (Walk 10)

Background

The mountains of Britain encompass one of the richest, most diverse landscapes to be found anywhere in the world, although for many hillwalkers the Highlands of Scotland are, more than any other region in Britain, true backpacker’s country.

Vast, open tracts of wild moorlands, high mountains, rocky coasts and long, winding glens make many Highland areas inhospitable to all except those willing to carry their own shelter and supplies, but in this wilderness there are many hidden corners where only the backpacker can explore. There are places that take days to reach on foot, where only the dedicated backpacker will venture – this is the preserve of the seasoned hillwalker, and wilderness exploration at its best.

Although many of our mountain and moorland regions are within easy reach of town and city, the northwest Highlands are more demanding of time and effort to get to for most of us, yet the rewards are all the greater for it. Some go to the northwest Highlands just or the superb walking, others go in search of rock to climb, wildlife to watch, rivers to canoe, or even whisky to drink, and many are happy to pursue all of these activities, and more, to an equal degree.

Many areas are best explored over a period of time, so for the weekend walker it makes sense to take a tent and sleeping bag on forays into the wilderness, and this is surely the best way of getting to know a particular part of the country. Crossing a range from end to end, or climbing a set of peaks around a desolate Highland glen, will introduce the walker to hitherto unknown regions, and if the trip involves the commitment of an overnight stopover or two, so much the better. To spend a night in a simple but comfortable shelter among lovely mountains, waking to a sunlit dawn of cackling grouse on vast, open expanses of purple moorland, or the guttural roar of rutting stags crashing around rocky slopes, is one of life’s great pleasures, and one that is only available to those with a will to discover these quiet places, and to make a temporary home among the mountains and wild shores.

But although there is much to be discovered within the mountain ranges of northern Scotland, some of the coastline and lesser hill ranges deserve mention too, for they are just as vital a component of our natural heritage as any of the higher regions. There is an almost limitless variety of backpacking routes throughout northern Scotland and its islands, all as good as each other in terms of the sense of achievement to be had from a successful trip.

Thirty of the greatest backpacking routes within the boundaries of northern Scotland and the northern islands are described here (for the purposes of this book I have taken the boundary between northern Scotland and southern Scotland as the Great Glen – that huge trench, with its string of lochs, stretching between Inverness on the Moray Firth in the northeast of the country, and Fort William on Loch Linnhe in the west). With the exception of Walk 23, which takes five days to complete, all the routes take either two or three days, with an overnight stop at a bothy or a youth hostel, or in a tent, either wild camping or at a recognised campsite.

All the routes should be suitable for a long weekend away among the hills, but I should add that although this book contains what are in my opinion the very best backpacking walks in the region covered, there is endless scope for further exploration. The routes described should be seen as an introduction – an aperitif perhaps – to the possibilities of other, longer routes that can be planned and tackled by those who have gained experience by following the ones included here.

The first book in this Backpacker’s Britain series covered northern England, and the second Wales. This is the third volume, on northern Scotland, and it is hoped that three more will follow, giving detailed backpacking routes in southern Scotland, southern England, and Ireland respectively.

How to Use This Guide

This book is aimed at anyone with a love of wild, mountain and coastal walking, but as many of the routes take the walker into remote and potentially dangerous terrain, you should ensure that you have previous experience of mountain walking and wild camping before tackling any of them. Good hill fitness is essential, as is the ability to accurately navigate using a map and compass (GPS, though a useful aid, is no substitute for the real thing!).

Walking through Glen Carnach (Walk 23)

Walkers in Knoydart (Walk 24)

The routes are ordered so as to move generally southwards, starting in Shetland and finishing in Lochaber. Most are circular, but a few are linear, and they range from those requiring two days to complete, through to a five-day traverse (see Appendix 3, Walk Summary Table, for more details).

It is difficult to suggest a best time of year for walking in Scotland – it can be great during any season. Generally speaking, mid-winter (January to March) will give very hard conditions with most routes snow-bound – but snow-holing instead of camping can be fun. April to June is a really good time to be in the Highlands, as the weather is often at its best then, and there are few midges, whereas July and August can be very hot and wet, and the midges are at their peak. September to December is also a very good time for a backpacking trip, and most of the midges will have gone to ground by then, but remember that you will have fewer hours of daylight in which to walk, and more time will be spent brewing up tea in tents or bothies!

Each route in the guide begins with an information box. This give details of the number of days needed, distances, height gain, and where to start and finish the walk. The Ordnance Survey Landranger maps you will need along the way are also included in this box. (Explorer maps are not necessary for backpacking in Scotland, as the extra detail given on them often doesn’t apply up here.)

For each route there is also an Area Summary and a Route Summary, followed by a box giving details of Tourist Information, Transport, Getting Around, Accommodation and Supplies and Escape Routes.

Note The sketch maps that illustrate each route are intended only as a rough guide – it is essential to take with you the relevant map.

Throughout the book incidental descriptive text is distinguished from the route directions, and place names from the sketch maps are highlighted in bold type to aid orientation.

Getting Around and Accommodation

The Scottish Tourist Board is a mine of information when it comes to planning trips into the hills – I really couldn’t have done without their help! Their website is useful for booking accommodation, as well as giving transport information – www.visitscotland.com (see Appendix 1, Useful Addresses).

Accommodation needs to be planned, and often booked, ahead. You will find anything from a simple campsite, to hostels, bed and breakfasts, guest houses, hotels, self-catering cottages and even castles, by contacting the Scottish Tourist Board. Accommodation is plentiful for most of the year, but be aware that many providers close for the winter season – from October to March – and checking ahead is essential during this time.

For most of the routes in this book it is definitely easier if you have your own car, but public transport is possible for many of them – details are given in the Route Information box at the start of each walk, and the Scottish Tourist Board can also give details of individual bus, ferry and flight companies.

Safety in the Hills

Great tomes have been written on this subject, and readers are referred to the specialist books suggested in the bibliography in Appendix 2, but for the most part, common sense is the main requirement. By this I simply mean going into the hills well equipped for the task in hand, both in terms of taking the right gear with you, and having the necessary navigation skills to accurately find your way in all weathers.

Many people stress the importance of leaving written word with a responsible party before heading off into the hills, and this is very good advice for those new to hillwalking, but for me, one of the real joys of hillwalking, and backpacking in particular, is the freedom it gives, including the liberty to change plans if, for instance, you have found the going easier than expected, or the weather has improved and you find yourself wanting to extend your stay in the mountains. This is not possible, and should certainly never be considered, if written word of your intentions has been left. The choice is up to the individual, and generally the best advice is to leave a route card, but if you do this you must stick to it rigidly. Obviously, if you choose not to leave a route card, you will be very much on your own should an accident occur.

A backpacker crosses a river on the way to Suilven (Walk 10)

Some of the hazards that you need to be aware of in the Scottish mountains are:

river crossings

cliffs

snow fields at certain times of year.

Rivers can rise and fall quickly in the Highlands, and people do die trying to cross them when in spate. Not all river crossings are by bridge – shallow water can be crossed quite easily by keeping your boots on (to avoid your feet being crushed by moving boulders or cut on sharp rocks) and facing upstream. However, if in any doubt at all, either find a way around, or camp and wait for the water level to go down.

Many of the routes in this book take you along narrow ridges and the tops of cliffs. The dangers here are obvious, but be aware that carrying a large backpack means that you will not be as agile as normal.

Any scrambles on rock included in the routes can be avoided by using the alternative route that is always given.

In spring there are often large areas of snow to cross, and carrying an ice axe and crampons is the sensible way to travel safely at this time (and it is of course essential that you know how to use them properly).

In an emergency, mark the position of the injured person on your map, then get to the nearest landline phone and call 999. Ask for the police and tell them you need a mountain rescue. The rescue team will come to the phone you are at and use your map to locate the injured person.

Hillwalkers on Mealaisbhal (Walk 5)

There’s some superb ridge walking above Glen Affric (Walk 20)

Mobile phone coverage is poor in Northern Scotland. If you do have a signal, emergency services can be contacted on 999, or you can use the international emergency code 112. It is also possible to call the nearest police station direct, if you key in the phone number beforehand.

Navigation

This is a subject that gets many people very flummoxed, and even some hillgoers who claim to have mastered it would struggle, should push come to shove. It is beyond the scope of this book to go into detail on this fascinating art, and it is hoped that anyone without navigation skills who is planning to head off into the hills would first book themselves onto a navigation course organised by professionals, or at least read a good book on the subject (see Appendix 2). Having said that, a few very general pointers are as follows.

The main skill to master is that of setting the map. To oversimplify things, it is perhaps best to point out that the top of all OS maps is grid north, and the red directional needle (the one that turns in the compass housing) points to magnetic north. It is an easy matter to place the compass on the map and turn the map around until this needle is pointing to the top of the map. This will then set the map in line with all the features on the ground – walls, fences, streams, hills – so that everything on the map is then in line with its corresponding ground feature. This is actually slightly flawed, as grid north and magnetic north are not exactly the same. Basically, the compass currently points slightly west of grid north. To correct you should add the difference as shown on the key on the edge of the map, but be aware that this magnetic variation changes slightly each year, and also varies according to whereabouts you are.

To measure distances on the map you need to know the scale – usually either 1:50,000 (OS Landranger maps) or 1:25,000 (OS Explorer, Outdoor Leisure and Pathfinder maps, and Harvey’s Superwalker maps). You can use the scale on the bottom of the map to find out how many millimetres on your compass represent 100 metres on the ground, and using this information you should be able to measure any distance on the map with some degree of accuracy.

So far so good, but then you need to know how many double steps you take to walk 100 metres. This obviously varies according to the size of your legs, so it is something you will have to work out for yourself. Most people take between 55 and 80 double steps to walk 100 metres, but bear in mind that this is on the flat, on a good surface. Your pacing will differ if you head uphill or downhill, and will also be different over rough terrain such as deep heather or soft snow. You can practise all of this by either going out with someone who already knows how many paces they take to walk 100 metres, or by going on a navigation course.

Another way of measuring distances, and the preferred method over longer distances (you don’t want to spend all day counting paces!), is timing. The average walking speed is 5 kilometres an hour (km/h), so at this speed it will take 12 minutes to walk 1000 metres (1km) on flat ground. Most people add 1 minute to the overall time of a set leg of the journey for every 10 metre contour climbed during that leg. However, for timing to be really useful you do need to know your own walking speed. I personally prefer to walk at 6km/h, but others may walk at 4km/h or even slower. The other problem with timing is that it will differ according to how heavy your rucksack is, or how tired you are, or the type of terrain you are walking over. It is best to experiment with timing over known distances to get the hang of it.

Wild camping at the head of Strathconon (Walk 19)

The only really effective way to learn navigation is out on the hills, initially by going on a course or reading a book, then by regularly practising the techniques on your own. Several useful books are included in the bibliography (Appendix 2) for those who want to learn, or brush up on, navigation skills.

Equipment

This is a very subjective matter. A browse through any outdoor retailer’s shop will reveal a bewildering array of boots, jackets, tents, sleeping bags, stoves, maps, compasses, and those little pouches for keeping your mobile phone safe and sound. In short, there is no shortage of gear and gizmos you can buy for the hills. Some of it is essential, other bits and pieces less so.

You will probably find that you already possess some of the essential items to get started in backpacking – most aspiring backpackers have been active in the outdoors previously, and will usually own a pair of boots, a waterproof jacket and overtrousers set, and probably a compass, map case, torch and first aid kit.

To head out for a night in the hills you will need to add a good sleeping bag to this list. There are basically two types of bag – down filled and synthetic. Down is lighter in weight but useless if it gets wet, whereas synthetic is heavier but retains some of its warming properties when wet. Synthetic is also usually a good deal cheaper than a better-quality down-filled bag.

A good mat under your sleeping bag is essential to keep you insulated from the cold ground beneath. Foam mats are cheap, but better is a Thermarest, which is air filled, far more comfortable, but much more expensive.

Then you’ll need a tent to put over yourself. I have used a number of different makes and models over the years, but for most people the best advice is to get the lightest tent you can for the seasons you intend to use it, and to pay the most you can afford – this latter point will automatically scrub all the next-to-useless models of tent from your shopping list. Recently I have been using a Hilleberg Akto, which really is superb for all-season camping, even in the wildest of areas. It is the lightest tent I have ever backpacked with, easy to pitch, and it gives me the confidence to go anywhere at any time of year.

Next you’ll need a stove of some sort. Gas is a popular fuel, while meths-burning Trangias are very often used by youth groups. The Trangia is a very safe stove, with the additional benefit of having no working parts to break. It is easy to light and easy to use, but does take a lot longer to boil water than almost any other camping stove I have used. Personally, I would always go for a Coleman Duel Fuel model. They are very efficient, and with one of these beauties you will be drinking your soup before your mates have even raised a bubble in their pots with other stove models.

As well as your camping equipment it is also a good idea to have spare warm, dry clothing in your rucksack for anything more than a single day in the hills.

Obviously you will need a rucksack larger than a daysack to carry all this extra kit, and again there are countless makes and models on the market. Go to an outdoor shop and try them all on, aiming for something around 60–70 litres in size. Get the assistant to fill the rucksacks with tents and other heavy gear, then walk around the shop to see which feels best. Once you set off on your backpack, aim to get everything into your rucksack, rather than hanging things on the outside. Apart from looking better, this also helps to distribute the weight more evenly, and will make for a more enjoyable backpacking trip.

Food

Food must be nutritious and palatable, and you should plan to carry enough to satisfy your energy needs for the duration of the trip, plus some spare high-energy food in case of emergency.

Generally speaking most people burn between 3000–4000 calories a day when they are backpacking, and it is recommended that you replace this throughout the day – a backpacking trip is not the time to go on a diet! Try to balance your daily intake so that you have around 60–65% carbohydrates, 25–30% fats and 10–15% protein, and aim to spread your food intake out over the day, eating little and often throughout the walk, rather than stopping for a huge food-fest at lunchtime, and spending the rest of the day feeling like snoozing it off!

Backpackers in Knoydart (Walk 24)

Having a rest en route for Dun Caan on Raasay (Walk 28) (photo: Beryl Tudhope)

On a backpacking trip it is difficult to eat similar foods to those you would normally eat at home, and the best advice is to experiment over different trips – indeed, this can become a great part of the whole backpacking experience.

As for spare emergency food, most people throw a few chocolate bars, flapjacks or high-energy bars into the bottom of their rucksacks. I know there are people who always eat their ‘emergency rations’ long before the trip is over, which of course is not ideal, and others deliberately take things that they don’t actually like eating very much, which is rather a good way of avoiding temptation. I have also heard it recommended that emergency rations should be wrapped in sticky tape, making it difficult to get into them, which is fine until an emergency occurs, and you still can’t get into them!

It is also essential to take in plenty of fluid, partly to replace that lost through sweating, and partly to help you digest food more efficiently.

Access and the Backpacker

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003 establishes access rights for everyone to most land and inland waters, provided they exercise them responsibly. These rights and responsibilities are set out in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code. For a copy of the code, call Scottish Natural Heritage on 01738 444177 or go to www.outdooraccess-scotland.com

Everyone has the right to be on most types of land to undertake outdoor activities such as walking, cycling and wild camping as long as they act responsibly. This means taking responsibility for your own actions in the outdoors, respecting the interests of other people using or working in the outdoors, and caring for the environment.

Red deer stags in the Fisherfield Forest (Walk 13)

Access rights don’t apply to any kind of motorised activity or to hunting, shooting or fishing. They also don’t apply everywhere, and exclude buildings and their immediate surroundings, houses and their gardens, and most land in which crops are growing.

Wild camping

Access rights extend to wild camping, which must be lightweight, done in small numbers, and only for two or three nights in any one place. Act responsibly by not camping in enclosed fields of crops or farm animals, and by keeping away from buildings, roads or historic structures. Take care to avoid disturbing deer stalking or grouse shooting activities. If you wish to camp close to a house or building, seek the owner’s permission. Leave no trace of your stay by removing all litter and any traces of your tent pitch or fire, and by not causing any pollution.

Stag-stalking season

This is usually from 1 July to 20 October, although most stalking takes place from August onwards (usually excluding Sundays). (The hind-stalking season is 21 October to 15 February.) During this period, you can help to minimise disturbance to stalking activities by finding out where stalking is talking place. Use the Hillphones service if available, www.snh.org.uk/hillphones, which gives recorded advice on where stalking is taking place, or pick up a Hillphones booklet in outdoor shops, hostels, tourist information centres or hotels. Although the code advises land managers to consider popular walking routes, paths and ridges when planning stalking you can also minimise disturbance to stalking by taking account of advice on alternative routes that may be posted on signs in the area. Deer control in forests and woods can take place all year round, often at dawn and dusk. Take extra care at these times and follow advice on signs and notices.

Flora and Fauna

The flora and fauna of the Highlands are fascinating aspects of this beautiful landscape, and worthy of whole volumes in their own right. However, I will summarise some of the more exciting species that the backpacker might, with a watchful eye and enough patience, come across during his or her wanderings in this area.

Fauna

Chief amongst mammals in the Highlands is the red deer, and put simply, there are far too many red deer wandering around in the hills. The lack of a natural predator is the problem – their numbers used to be kept down by wolves, but our ancestors managed to get rid of those. Too few deer are being culled, and although some estates are very good at culling, numbers of deer are still increasing. This might sound like wonderful news in one sense, but it also means that there simply isn’t enough land to support the huge numbers of deer on it – a recent estimate is around 700,000 in the Highlands. Many deer starve to death in winter, but as breeding numbers are high, the population still continues to grow. So taking all this into account, you’d be very unlucky not to see at least some red deer while out backpacking in the wilds (although you won’t find deer in the Northern Isles).

Of the larger birds, ravens, buzzards and golden eagles are the species most likely to be seen. Raven numbers are decreasing, but buzzards and golden eagles are doing very well. On all the mainland walks in this book you could enjoy good views of these birds, but again they are pretty much absent from the Northern Isles.

Other predators to look out for include otters, the pine marten and Scottish wildcat. Of these, you are most likely to come across otters, particularly on any of the walks on the west coast, although there are also very high numbers in Shetland, and a fair few in Orkney, so if you’re quiet you might just be lucky.

On ferry crossings you should look out for seals, both common and grey, while cetaceans (dolphins and whales) are often seen. In particular, you should keep your eyes peeled for bottle-nosed, common and even Risso’s dolphins, the minke whale and the harbour porpoise. Humpbacked whales have been seen around the Small Isles, and this also seems to be a fairly regular area for basking sharks.

Back on dry land there are always red grouse on the moors, and here you should also see curlew, dunlin, snipe and golden plover in the breeding season. Mountain tops are not without wildlife either – you’ll find the snow bunting, ptarmigan and mountain hare.

Sunset over the Black Cuillin from Knoydart (Walk 25)

In woodland you might see the secretive roe deer, while the trees attract red squirrels and many small birds. In ancient pine forests, such as in Glen Affric, there’s also a chance of seeing the crested tit and Scottish crossbill, which is unique to Scots pines in the Highlands.

All these species are best viewed from a distance – indeed, you will no success at all if you try getting too close to birds and mammals, and it is actually illegal to deliberately approach many nesting birds. It is obviously sensible not to try to get anywhere near deer, either, particularly during the rut, when the males will see you as competition – and they do have very big antlers!

Flora

It is also illegal to pick wild flowers, and there are plenty of these to be seen in the Highlands. Specialities include bog asphodel, bog myrtle, ling, bell and crossed-leaved heathers, lousewort, milkwort, cow wheat and a whole range of orchids. Bilberry and crowberry can be seen on high mountainsides, and occasionally you might come across bearberry and cowberry.

Each region and island has its own specialities, which can make the study of the flora of Scotland particularly fascinating, and while you are not likely to want to suffer the extra weight of a field guide to flora when backpacking, doing a bit of research before a trip can greatly heighten the enjoyment when you stumble across your first grass of Parnassus, spring squill or dwarf cornel!