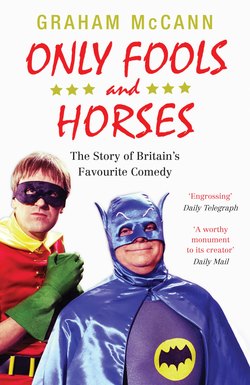

Читать книгу Only Fools and Horses - Graham McCann - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

This Time Next Year

Répondez s’il vous plaît.

It is September 1980. This time next year . . .

This time next year, a writer called John Sullivan will begin a labour of love, a producer/director called Ray Butt will commence an extraordinary adventure, a trio of actors named David Jason, Nicholas Lyndhurst and Lennard Pearce will take on the roles of their dreams and a brand new sitcom entitled Only Fools and Horses will start to enrich a great comic tradition. Nothing seemed inevitable back in September 1980, but, this time next year, something will arrive on British television that will end up being seen as very special indeed.

In 1980, however, the immediate future, to many British people, seemed bleak. The new Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was busy reassuring her monetarist minions that she was most definitely not for turning. After wrongly attributing her implausibly tolerant initial sentiments (‘where there is discord, may we bring harmony . . .’) to the medieval theology of St Francis of Assisi (they actually came from an obscure 1912 French prayer), and wrongly associating her modern amoral economics with the eighteenth-century moral philosophy of Adam Smith (she favoured the free market for its own sake; he favoured it because he believed good and decent people would not abuse it), she proceeded to brand any colleagues who possessed more logic but less blinkered conviction than her as ‘wet’, and set about causing as much discord as seemed politically possible. There were bitter industrial disputes and violent riots, rising inflation and falling factories, and, while two million or so freshly ‘unfettered’ Britons remained miserably unemployed, self-interest was celebrated at the expense of civic virtue. Council tenants were invited to buy their own homes, so even if they were stuck on a low social rung they could at least console themselves with the thought that they now owned a tiny splinter or two of the ladder, and a few individuals who feared being stuck in dead-end jobs began to buy into the dubious entrepreneurial dream of class-free upward mobility, but in any other sense most ordinary working people were left alone to deal with the mounting mood of despondency and desolation.

British comedy failed, for a while, to be of much help. The Prime Minister herself had wasted no time in demonstrating that she had no real sense of humour (even before her election triumph in 1979, when handed a light-hearted line – ‘Keep taking the tablets’ – to mock her Labour rival James Callaghan’s likening of himself to Moses, she attempted to ‘improve’ the joke by saying ‘Keep taking the pills’ instead1), and many in the comedy industry seemed to respond to such tin-eared forays into funny business by losing their own invaluable talent to amuse.

While most of the old bow-tied brigade now appeared more energised by the prospect of playing a round of golf than they were by the challenge of making people laugh, and several much-loved but ageing greats (including Morecambe & Wise, The Two Ronnies and Tommy Cooper) had already slipped into a slow but inevitable decline, the only notable sign that a younger generation of comics might one day be ready to take up the reins was the recent arrival on television of the mildly irreverent sketch show Not the Nine O’Clock News. Not even sitcoms – so often the most humorously attuned to their times – seemed quite ready to engage with the start of the Thatcher era.

Some hugely popular and critically praised sitcoms had come to an end in the second half of the 1970s: Dad’s Army and Porridge in 1977, The Good Life and Rising Damp in 1978, and Fawlty Towers in 1979. As the 1980s approached, the genre, slouching down somewhere between the humdrum and the ho-hum, was suddenly looking more than a little jaded.

‘For the past couple of weeks,’ one frustrated TV critic remarked, ‘I have, in the line of duty, been sampling as many of the current crop of comedies as a body, if not mind, could bear without actual pain. I thought I might offer a considered survey of the scene, but in the name of charity, I’ve given that up. A critic cracking at one unlovable comedy risks sounding like a sledgehammer of pompousness descending on a lark’s egg, but with a list a dozen long . . .’2 A few new series were starting – most notably To The Manor Born and Terry and June in 1979 – but they seemed much safer, and more self-consciously and exclusively middle-class, than most of their illustrious predecessors. The great British sitcom was in danger of falling dramatically out of fashion.

All of this, however, was soon to change. All that it would take was a certain combination of talents and ambitions, this time next year.

The writer who would change things was John Sullivan. The producer/director was Ray Butt. The actors were David Jason, Nicholas Lyndhurst and Lennard Pearce.

John Sullivan was a somewhat stocky but rather shy and softly spoken scriptwriter who, by 1980, suddenly found himself at an unexpected crossroads in his career. After working hard to establish himself at the BBC by shaping a popular sitcom, he was now facing his first real professional crisis.

Born John Richard Thomas Sullivan in 1946 to an Anglo-Irish, Kentish-Corkish family based in the south London district of Balham (‘Gateway to the South’, as Peter Sellers’ legendary cod-travelogue dubbed it), he had experienced an upbringing that, as he would later put it, was almost clichéd in its working-class character. His father, also named John, was a plumber by trade, and his mother, Hilda, worked occasionally as a charlady. They shared a small terraced house in the rough and tough area of Zennor Road with another family, and made do with such basic amenities as an outside lavatory and an old tin bath hanging up in the yard.

School struck John Jnr as an unwelcome and irrational distraction from both his early love of football and his mounting impatience to get out in the world and start earning a regular wage. The challenge of the eleven-plus examination therefore came and went without ever threatening to shake him out of his educational apathy. Feeling fated to become mere factory fodder, he reasoned that there was no real point in trying. The only ‘encouragement’ to at least appear to study, as far as Sullivan and his friends were concerned, was the prospect of avoiding a gym shoe being slapped across the backside and a piece of chalk hurled sharply at the head. His nascent gift for using his imagination was limited in those days to twisting the truth in the classroom: selling freshly tailored lies – cash up front – to those pupils in urgent need of plausible excuses to tell the teachers. It was only in 1958, when Sullivan reached the age of twelve while at Telferscot Secondary Modern School in Radbourne Road, that he finally started taking an interest in something academic: English Literature.

The reason for this was that he found a new young teacher – Jim Trowers – who stopped making English Literature seem remotely academic. The Geordie-born Trowers looked somewhat unconventional – his hair was a little longer than the norm, he wore a patch over his right eye (which he would sometimes pretend to take out and clean) and seemed full of nervous energy – and, mercifully for Sullivan and others, he taught unconventionally, too. Instead of the robotic ‘read, absorb and regurgitate’ method employed by previous teachers, which had bored young Sullivan to tears, Trowers took each story and read it out to his pupils, adopting a range of voices and tones and rhythms to bring all the scenes and characters to life. Suddenly, for Sullivan (who had grown up in a home that contained just two books on its shelves – The Bible and a guide to the football pools), literature made sense – and, more than that, it started to matter. Dickens’ David Copperfield sparked a real interest in English as a subject, and in writing. The mid-twentieth-century schoolboy found himself enthralled by colourful descriptions of areas, social groups and characters that were very familiar to him. Dickens became his favourite author, and Sullivan had something other than football to look forward to in his school day.

Structured and paced for the old shilling monthlies, Dickens’ cleverly episodic stories had the kind of social scope, and humour, that engaged Sullivan’s youthful imagination. Each fiction seemed to offer a broad range of characterisations that captured the full richness and complexity of the Victorian social hierarchy. In Bleak House, for example, level after level was acknowledged and explored: there were the lofty Dedlocks in their West End mansion; lesser landowners like Mr Jarndyce and members of older professions such as the lawyers Mr Tulkinghorn and Mr Vholes and the doctor Allen Woodcourt; figures from the middling classes that included the northern ironmaster Mr Rouncewell, the campaigning Mrs Jellyby, the shop owner Mr Bagnet and the moneylender Mr Smallweed; the marginal types, such as the detective Inspector Bucket, the rag-and-bone man Mr Krook and the shooting gallery man Mr George; the servants, ranging from the superior housekeeper Mrs Rouncewell down through the ladies’ maids to the poor dogsbody Guster; and, at the bottom, the manual workers, Neckett the sheriff ’s officer, and the inarticulate and homeless crossing-sweeper Jo White. No part of the community seemed excluded or overlooked; no aspect appeared under-appreciated. Such fictions struck Sullivan as powerful, plausible and persistently vivid visions of real life: ‘Dickens wrote about areas I knew in London; although the writing dated back to the early 19th century, I felt this guy knew where I’d been and I began realising just how special his books were.’3

Sullivan’s sudden interest in such literary works was soon spotted by Jim Trowers, who was intrigued by the kind of work that the boy was now producing. ‘I gave the class an essay to write,’ the teacher would recall. ‘I said to them: “You have the Epsom races. Write me a short piece from any aspect at all. You know, perhaps one of the bookies, or someone laying a bet.” And they all did this. Except John Sullivan. He wrote it as though he were one of the horses running the race. Which I found absolutely fascinating.’4

In spite of this belated academic enthusiasm, however, Sullivan still chose to leave school three years later, aged fifteen, without sitting for any qualifications. This was the norm among working-class families, where the pressure to contribute to the family’s income often outweighed any sense of individual aspiration. Staying on to sit for O levels was still largely a middle-class privilege.

Rather than being forced straight into one of the local factories, Sullivan found his first job instead working as a messenger for the news agency Reuters, in Fleet Street, in the autumn of 1961. A few months later, after a brief spell helping out in the company’s photographic department, he reverted to being a messenger once again, this time at the new and very à la mode advertising agency of Collett, Dickenson, Pearce & Partners (CDP), a small but rather glamorous Mad Men-style outfit based in Howland Street, west central London, where the likes of future filmmakers David Puttnam and Alan Parker would soon be making a name for themselves (the former as an accounts executive, the latter as a copywriter) alongside the advertising wunderkind Charles Saatchi. In 1963, at the age of seventeen, Sullivan, attracted by the prospect of increasing his weekly wage from £3.50 to £20, was persuaded to join his old school friend Colin Humphries cleaning cars for a local second-hand car dealer. He and Humphries then went on to try their hand at selling cars themselves, but Sullivan soon realised that he was not suited to the vocation and drifted off to work for Watney’s Brewery in Balham instead.

It was here during the mid-1960s, stacking crates in a large and noisy hall, that he first started to consider pursuing writing as a more fulfilling kind of career. One of his co-workers was another old school friend called Paul Saunders, with whom he shared jokes and funny stories during the many boring periods of inaction. In January 1968, Saunders told his friend that he had recently read an article in the Daily Mirror about Johnny Speight: the famous working-class boy from Canning Town who grew up to write grittily realistic and socially aware plays, and then the hugely successful and notoriously controversial sitcom Till Death Us Do Part, and, as a consequence, was now winning prestigious awards and commanding a fee of around £1,000 per script.5 Sullivan was intrigued, and so, when Saunders suggested that they should try to follow in Speight’s footsteps (‘We’re funny guys. We should have a go at this and earn a load of money!’6), he agreed, and promptly went out to buy an old typewriter from a local second-hand shop called The Treasure Chest.

For the next two months, the two young men worked on an idea – involving an old soldier whose pride and joy was the traditional gents’ public lavatory that he ran, but who is now faced with competition from a brand-new modern rival down the road – and, when they felt it had developed satisfactorily, sent off a sample script to the BBC. Three more months passed, while the two young men packed beer crate after beer crate and dreamed of emulating Johnny Speight with his Rolls-Royce, big house in the country, champagne, cigars and glamorous celebrity lifestyle. Then a reply finally arrived: ‘We are not looking for this kind of material.’

The brusque rejection sapped the spirit of Saunders, who decided to dream about doing something else, but Sullivan was undaunted: He had discovered that he enjoyed the process of writing and therefore continued to write and work on scripts: ‘I so enjoyed the process of inventing characters and writing the dialogue that it just became a hobby. It kept me off the streets, and I didn’t spend too much money on beer, because I was just writing every evening. And I suppose the dream was that, yes, I still hoped I could get into this business.’ Drawing from his own experiences, he based his plots and characters on themes and people that he knew and set them in familiar, local locations. One idea revolved around a family called the Leeches, who fiddled to keep feeding off the State; another featured a football team that always failed to find the winning formula. As soon as each sample story was completed, he sent them off to the BBC and waited patiently for a letter of acceptance. When all that he received was a rejection slip, he simply rewrote the script and sent it straight back in. ‘Sometimes I’d change the titles, sometimes I’d even change my own name, to try to fool them’.7 He refused to accept defeat.

Working-class heroes continued to offer him hope as the 1960s edged towards their end. Apart from Johnny Speight, Sullivan could also look at Ray Galton and Alan Simpson – two other hugely gifted writers from very modest London backgrounds who had reached the top of the profession (and whose 1962 pilot episode of their sitcom Steptoe and Son, which had featured bright comedy mixed with raw emotional drama, had dazzled Sullivan when he first watched it) – along with such inspired musicians and lyricists as the Muswell Hill-born Ray Davies of The Kinks and the Chiswick-born Pete Townshend of The Who, and, right at the heart of the decade’s pop culture, Lennon and McCartney of The Beatles were continuing to confound Britain’s old class prejudices. ‘I can remember lying in bed and hearing one of their songs, “From Me To You”, playing down the street,’ Sullivan would recall fondly about the so-called Fab Four. ‘I’d never heard anything like it before, it was such a different sound. I’ll always remember thinking: “Aren’t the Americans clever.” I automatically assumed that any new sound, anything good, originated from the States, so when I found out that they were four working-class boys from a few hundred miles up the road, I was really inspired.’8 It was still possible, Sullivan kept telling himself, in spite of the old social bias; there was still a chance for an ‘ordinary’ young man from Balham to make it big via the uses of literacy.

While the challenge of writing continued to inspire him, however, the dull routine of the day job continued to bore him, so he left Watney’s and, for want of another way to earn a regular wage, went to work with his father as a trainee plumber. It did not take long for him to realise that he had made a great mistake: he had no real interest in plumbing and was consequently careless, causing frequent floods.

Determined to find a way to better himself before it was too late, he resolved to teach himself some of the things that he had allowed to pass him by during his days at school, devouring books on a wide range of subjects and trying his best to broaden his knowledge. He also continued to write in his spare time, still hopeful that, one day, an idea would spark something genuinely special. As what he called a ‘brain exercise’, he would open newspapers on random pages (just like he had heard that John Lennon had done prior to conjuring up such songs as ‘A Day In The Life’) and pick out a story to use as source material for a script. The ambition remained unabated.

He was still labouring as a maintenance plumber while striving to develop as a writer when, in 1972, he met an attractive young secretary called Sharon in the upmarket Chelsea Drugstore pub (mentioned, rather ominously, in the Rolling Stones song ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’) on the King’s Road. They got on well, and started dating, but Sullivan went out with her a few times before daring to mention his dream of exchanging his tool kit for a typewriter. Sharon was earning more than he was at the time, but, in spite of any misgivings she might have felt, she continued seeing him and listening to his writerly ambitions, and, two years later, they married.

Sullivan – now living with Sharon in a two-roomed council flat at Rossiter Road in Balham – kept up his strategy of bombarding the BBC with sample scripts, and refused to be disheartened by any rejection letter that came back: ‘I used to drive past the BBC’s TV Centre in west London and I used to look at it like a castle that I had to somehow or other breach.’9 One day, he came up with an idea for a sitcom that really captured his imagination: an unemployed young man from south London who had convinced himself that he was a dangerous revolutionary and the self-appointed leader of the ‘Tooting Popular Front’.

‘I knew it was my best idea yet,’ said Sullivan, who had known such a character in a local pub (The Nelson Arms) who was always spouting radical political clichés while never seeming to do anything remotely practical. During an era in Britain when there seemed to be a bewildering array of Marxist, Western Marxist, Marxist–Leninist, Trotskyist, anarchist, anarcho-syndicalist, revolutionary socialist and neo-communist splinter groups arguing angrily amongst each other, and it almost seemed de rigueur for students to decorate their walls with blood red Che Guevara posters while parroting some or other type of clumsy political jargon (a fashion mocked with great relish by Private Eye via the umming and erring character of ‘Dave Spart’), the relevance of the comic theme was abundantly clear. Calling his proposed sitcom Citizen Smith, Sullivan worked hard on the sample script – believing that its topical revolutionary theme had real potential – and then pondered the most appropriate strategy for submitting it. Knowing that the script represented his best work yet by far, his greatest fear was rejection, and what he would do if it failed to work out.

Determined not to squander this opportunity, Sullivan considered his options as carefully as possible and concluded that his best chance would be to adopt a Trojan Horse-style strategy: get a very basic job at the BBC, learn from within how the organisation functioned and then seek out a suitable patron. He thus applied to the Corporation, on 19 September 1974, and, much to his surprise, was not only invited for an interview but subsequently (on 18 November) given a position in the props department at Television Centre. Feeling emboldened by his good fortune now that he was finally inside the ‘castle’, he soon engineered a move to scene shifting, which brought him closer to the actual business of filming, and started studying who did what on the set.

One evening, as he went about his usual duties, a colleague pointed out someone – a tall, stick-thin, chain-smoking individual – who was deemed to be very special indeed: Dennis Main Wilson. The name, at least, was well-known to Sullivan, as indeed it was, at the back of their minds, to millions of other comedy fans. Dennis Main Wilson was the name that had been heard, as producer, at the end of countless popular radio shows, including Hancock’s Half-Hour and The Goon Show, and was the name that appeared at the conclusion of some of the BBC’s most admired television sitcoms, including The Rag Trade, Sykes and A . . . and Till Death Us Do Part. He was one of the Corporation’s most experienced, influential, outspoken and independent-minded producer/directors, having worked there since the early 1940s and battled long and hard to keep the meddling ‘management’ a safe distance away from himself and the talent. The running joke among some of his colleagues was that he was rarely to be seen without sporting two pairs of glasses – one on the bridge of his nose and the other pair, one containing beer and the other one whisky, in his hands – but nobody doubted his passion for programme-making.

Sullivan knew, immediately, that this was a man who, if he liked a new idea, would really fight for it to reach the screen. Somewhat intimidated by the double-barrelled name and what seemed from a distance to be a brash and brusque ‘RAF officer’ sort of manner, the would-be scriptwriter was anxious about making contact with such an eminent broadcasting figure, but, eventually, he plucked up the courage to sneak into the crowded BBC bar – where Main Wilson was known to go through the daily lunchtime ritual of sipping half a pint of bitter followed by a small glass of Bell’s whisky – and make himself known. ‘I said, “I thought I’d introduce myself, my name’s John Sullivan, because we’re going to be working together soon.”’10 Main Wilson, understandably, thought Sullivan would be working on one of his shows, but, upon discovering that this props man was actually proposing a script, was sufficiently impressed by the sheer gall of Sullivan’s approach to offer some friendly advice and encouragement over a drink.

Main Wilson was a good choice as a potential patron. Born in Dulwich and grammar school-educated, he remained, at least by the traditional standards of the BBC, something of a maverick (acutely suspicious of authority since the war, when one of his jobs was writing satirical anti-Nazi propaganda for broadcast all over Europe, he empathised instinctively with the workers on the studio floor no matter how high he rose up the TV hierarchy), and he rather enjoyed the unpredictability that came with the more unconventional of creative spirits. This, after all, was the man who had won the trust and respect of the likes of Spike Milligan, Tony Hancock, Eric Sykes, Peter Sellers, Marty Feldman, John Fortune, Barry Humphries and Johnny Speight. He was no romantic – having been through a hard war, he was realistic to the verge of seeming cynical – but he seized on anything and anyone that struck him as genuine and lifted his spirit.

He had been the one, for example, who in the late 1940s had responded to an audition from a young scriptwriter/stand-up named Bob Monkhouse by eschewing the standard BBC marking system and simply sending on a memo that said: ‘WOW!’11 He had also been the one who, early in the 1960s, had spotted the potential in a modest production exercise by a trainee director called Dick Clement (who had co-written a comic story with his friend Ian La Frenais), and thanks to Main Wilson’s enthusiasm and energetic support the project ended up growing into The Likely Lads. Writers always fascinated him and, when he found good enough reasons to have faith in them, he became their finest and fiercest ally.

Main Wilson’s immediate advice to Sullivan was for him to sharpen his skills and heighten his profile by going off and attempting to write sketches for shows such as The Two Ronnies. Sullivan did as he was told, and, once he had some material (revolving around two Cockney blokes – Sid and George – chatting in a pub), he took advantage of the fact that he was currently working on the set of Porridge by slipping the scripts to Ronnie Barker. The following week, Barker called Sullivan over, asked him if he thought he would be able to come up with any more material, and then arranged for him to be put on a contract. The budding scriptwriter was suddenly in business.

The Sid and George sketches would become a familiar ingredient in the rich mix that made The Two Ronnies so entertaining. Featuring several themes and conceits that anticipated Sullivan’s later work (malapropisms, such as, ‘You don’t like birds, you’re illogical to feathers, ain’t you?’; slyly sardonic put-downs, such as describing the point of human existence as ‘something to do, I suppose’; and a succession of dubious deals, including the duck sold as a racing pigeon, the hamster passed off as a ‘day-old Labrador pup’ and a digital timepiece described as ‘an Elizabeth I wristwatch’), the routines bubbled with comic promise. What was also already evident was Sullivan’s delight in drawing together two characters, and drawing out two personalities, through dialogue:

| SID: | You back, George? |

| GEORGE: | No, no, I’m still down there, Sid. |

| SID: | Eh? |

| GEORGE: | What you’re staring at now is one of those uncanny encounters of the third division, see, probably due to the time warp on the A33 between Croydon and the coast. |

| SID: | Eh? |

| GEORGE: | ’Course I’m ’ere! |

Sullivan was soon submitting material not only to The Two Ronnies but also to shows hosted by the likes of Dave Allen, Les Dawson and Barry Took. Like such fellow budding sitcom writers as David Renwick (One Foot in the Grave) and David Nobbs (The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin), Sullivan first learned to write for an ensemble of actors by contributing to these kinds of programmes. Obliged to supply precisely timed lines as well as sharply structured sketches, some of it bespoke for certain performers and some of it left hanging for anyone to pick up off-the-peg, he was learning his craft at a rapid rate.

It was not long after this first set of ad hoc commissions began that Dennis Main Wilson, impressed by Sullivan’s progress, encouraged him to start working on his idea for a sitcom. Greatly excited, Sullivan promptly took two weeks’ leave and went to his in-laws’ home in Crystal Palace, where he locked himself away and laboured until he had a proper pilot episode fully scripted. Meeting once again in the BBC bar, Main Wilson speed-read it in twenty minutes and loved it, and, as he later recalled, resolved there and then to make the project happen:

I said ‘I’ll buy it,’ even though the scene had changed, and I wasn’t in a position to buy officially. But under my old thing I would have been, so sod it, ‘I’ll buy it.’ If [the BBC don’t want it] I’ll bloody sell it to ATV or something. And I bought it and luckily our Head of Comedy in those days was Jimmy Gilbert [ . . . ] and I bashed into his office and said ‘Read that!’, and anybody who works in light entertainment and is a boss, poor devil, the number of scripts that come in, even if they’re filtered by script editors . . . But I said to Jim, ‘Read that, not at the top, not at the bottom of the thing – now! We’ll be in the bar.’12

Gilbert – well used to his old friend’s passionate attitude, and already impressed by Sullivan’s efforts for The Two Ronnies – read it, then sought out the two men in the bar and agreed that the Citizen Smith script merited inclusion in the next series of Comedy Special (the successor to Comedy Playhouse, the BBC’s traditional showcase for testing the audience reaction to promising sitcom pilots – and the birthplace of, among several other memorable shows, Steptoe and Son and Till Death Us Do Part). ‘I actually liked the script so much,’ Gilbert would recall, ‘that I immediately asked John for a back-up script, just to make sure that he would be able to maintain the quality, and that turned out to be equally good, so I then went straight ahead and commissioned a whole series before the pilot had even gone out.’13

The commissioning process – in stark contrast to the painstakingly slow and neurotically over-elaborate procedures favoured by today’s major broadcasters – was remarkably simple, straightforward and quick. ‘In those days,’ Gilbert explained, ‘if you were a head of a department at the BBC, and you wanted to make a programme and get some facilities, you just walked upstairs. I went up to see the Controller of BBC1 and told him I’d got this splendid script. So he got his planner in to see if there was space and get some money out of the budget. And that was it. The whole thing was fixed.’14

Sullivan – celebrating with an expensive round of drinks – could hardly believe what was happening. After years of sending in scripts and waiting in vain for something positive to happen, his latest idea was now being fast-tracked into production. A mere six weeks later, on 12 April 1977, the first episode was broadcast on BBC1.15

Directed by Ray Butt (a genial but industrious Londoner whose previous projects included The Liver Birds, Last of the Summer Wine, Are You Being Served?, Mr Big and It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum) and starring the up-and-coming actor Robert Lindsay as the workshy radical ‘Wolfie’ Smith, and Lindsay’s then-wife Cheryl Hall as his sweet-natured and far more conventional girlfriend Shirley, the pilot went well and a complete series was promptly commissioned. Also featuring Mike Grady as Wolfie’s woozily religious flatmate Ken, Anthony Millan as their fearful fellow-suburban guerrilla Tucker, and Peter Vaughan and Hilda Braid as Shirley’s parents (and with a theme song – ‘The Glorious Day’ – written by Sullivan), the show went on to prove itself a considerable success, building up a solid following over a run that would last for four series from 1977 to 1980.

As a sitcom, it stayed loose and light – the storylines tended to stick to a very small and predictable range of topics, usually involving bungled protests and brushes with the law, and the characters never really acquired any depth or drive – but, at its heart, was the engagingly Walter Mittyish figure of Citizen Smith himself, the sheep in wolf ’s clothing who fooled no one except himself:

| WOLFIE: | We in the Tooting Popular Front are massing our forces ready for the big push! |

| SHIRLEY: | How many of you are there? |

| WOLFIE: | Ha! How many? How many fish in the sea? How many stars in the sky? |

| SHIRLEY: | How many, Wolfie? |

| WOLFIE: | Six. |

Brightly written and nicely played, the character struck a contemporary chord, especially with younger viewers, and kept people interested and entertained even when the plots started to pall. Without inspiring any critic to hail it as a classic, the majority of those who previewed and reviewed it treated the show with a fair measure of warmth and affection, and came to see plenty of potential in John Sullivan as a sitcom writer. As he prepared to move on to his next project, therefore, the future seemed excitingly bright.

It was in 1980, however, that Sullivan suddenly found himself in trouble. After bringing his first sitcom to a satisfying close, his initial idea for a second one – Bright Lights, about a naive northern boy who comes to London in search of glamour and excitement – was scrapped at the planning stage and then he also lost the next one that he wrote before it had even reached the screen.

It was called Over the Moon, and was about a hapless football manager trying in vain to turn a lower-league football club into the next big thing. A pilot episode had been recorded on 30 November in a studio at Television Centre, and, although one or two who saw it had misgivings about its potential (Jimmy Gilbert, for example, felt that, compared to the first edition of Citizen Smith, ‘it hadn’t worked out so well’16), it was well enough received internally for the BBC to commission an initial series of six episodes. Sullivan was very optimistic about its prospects: the cast – which included Brian Wilde (best known at the time for playing the permanently befuddled prison officer Mr Barraclough in Porridge) as the manager and George Baker (a familiar face since becoming a British movie star in the 1950s) as his chairman – looked strong, the producer/director was Sullivan’s friend and old Citizen Smith colleague Ray Butt, and the situation itself – dealing as it did with the old-style working-class milieu of pre-Premiership football – was something that Sullivan knew well, and loved sufficiently to make it seem plausible as well as funny. It therefore came as a shock when, just as he was in the middle of writing the fourth instalment, the call came from Ray Butt that Bill Cotton, the then-Controller of BBC1, had returned from a trip overseas and promptly cancelled the commission.

The explanation Butt was given was that, as the Corporation had previously committed itself to making a brand new sitcom about a boxer (Seconds Out, starring, ironically, Robert Lindsay), it was decided that one comedy with a sporting theme was quite enough for the time being, so Over the Moon was dropped like a sick parrot. It was disastrous news for John Sullivan, because he and his wife had just had a baby and taken out a mortgage on their first house in Sutton, Surrey. Only under contract at the BBC for one more year, the future, financially, suddenly looked ominously bleak.

While the scriptwriter and his erstwhile producer/director busied themselves with finding a solution to the problem, three actors were facing their own challenges as 1980 moved towards its end. David Jason was still searching for the role that would establish him once and for all as a bona fide star; Nicholas Lyndhurst was looking for the chance to advance his fledgling career; and Lennard Pearce, having been in the business for the best part of fifty years, was finally pondering the possibility of retirement.

David Jason, at the time, was by far the best known of the three performers, but in 1980, after being touted for years as a big star in the making, he was still regarded by many as nothing more than a top-class support act. Although his thick dark hair was sometimes disguised with a variety of coloured wigs, his diminutive stature (5feet 6inches tall), large and dark orbital eyes and wide thin-lipped grin were familiar to many viewers after seeing him in numerous supporting roles, but some still responded to his presence in the credits with the question, ‘David who?’17

Born David John White on 2 February 1940 (sadly his twin brother, Jason, lived for only two weeks), he came from a similar working-class background to that of John Sullivan. His father, Arthur, was a fish porter at Billingsgate Fish Market. His Welsh mother, Olwen, was a charlady. The family home was a small terraced house in Lodge Lane in Finchley, north London.

He was always a gifted mimic, and found it easy to amuse his family and friends with impersonations of popular radio stars, but acting only became important to him after he took part, at the age of fourteen, in a school play about the English Civil Wars. Grudgingly standing in for an ailing classmate, he appeared as a cavalier and, much to his surprise, loved the experience and, after it was over, resolved to remain on the stage by joining a local amateur dramatic society.

He left school at fifteen, and tried to honour his parents’ wishes by training for a trade, working first as a mechanic and then as an electrician. His real ambition, however, was to make acting his proper profession, and he spent his spare evenings treading the boards in amateur productions. He received his first notice in July 1955, when a local drama critic named W.H. Gelder spotted his potential and praised his performance in the Incognito Theatre Group’s production of the St John Ervine play, Robert’s Wife. Further reviews by Gelder appeared in the Barnet and Finchley Press, including one that applauded David’s efforts for another local amateur dramatic group, The Manor Players: ‘[T]he extraordinarily precocious schoolboy by David White, looking like a young James Cagney, and playing, though only 16, with the ease of a born actor [was] possibly the highlight of the evening, which was bright enough in all conscience . . .’ Gelder would also write that the young actor was ‘one of the comparatively few amateurs whom I could conscientiously recommend for the professional theatre’. The critical plaudits delighted the amateur actor, who saved all of Gelder’s reviews and made sure that they did not escape his parents’ attention.18

By his early twenties, David was working during the day as an electrician alongside his old friend Bob Bevil for a company the two men had set up called B & W Installations, but, even though the business started to do quite well, he never stopped listening and looking out for a serious chance to perform. The opportunity finally arrived in March 1965, when his elder brother Arthur, who had himself started acting professionally, was offered a part in the popular BBC police drama series Z Cars; in order to accept, Arthur had to abandon a forthcoming engagement (to play the minor part of a coloured butler called Sanjamo) in a play – Noel Coward’s The South Sea Bubble – at Bromley Rep in Kent, but, before dropping out, he recommended David to the director, Simon Oates.

The recommendation worked: after watching David in an amateur production, Oates judged him a ‘stunningly talented’ actor and signed him up.19 Thrilled to be given such an opportunity, David promptly surrendered his share in B & W Installations and made his professional debut as an actor on 5 April 1965 at Bromley Rep. He followed this with a few more minor engagements before returning to the repertory company on a twelve-month contract. It was here that he served his theatrical apprenticeship, submitting himself to the discipline of Rep’s rapid rotation of roles, tones and themes. Always a very private man (‘The only person who knows me,’ he would say, ‘is me’20), as well as a very driven one, he submerged himself in his work, relishing the opportunity to concentrate on each distinctive characterisation.

After Rep, Jason acquired an agent – Ann Callender, the wife of the BBC producer/director David Croft, who was based at The Richard Stone Partnership – and adopted the stage name of Jason (possibly in honour of his late brother, although he once claimed that it was prompted by his fondness for Jason and the Argonauts) after discovering that there was already a ‘David White’ on Equity’s books. He then proceeded to work in a wide range of plays and summer seasons.

His first major break on television arrived in 1967, when he became a regular member of the new ITV children’s comedy show Do Not Adjust Your Set alongside the future Monty Python stars Eric Idle, Michael Palin and Terry Jones and the versatile character actor Denise Coffey. Overseen by the producer Humphrey Barclay (who had been recruited specially from the BBC with the brief of creating a bold new brand of ‘adult’ comedy shows for youngsters), Do Not Adjust Your Set was, for the time, an intriguingly adventurous and imaginative sketch show that mixed silliness with surrealism to appeal beyond the normal audience for its modest tea-time slot. Among Jason’s regular contributions was his role as Captain Fantastic, a comically British bowler-hatted and moustachioed super-hero drawn into a succession of darkly slapstick situations. His very physical Buster Keaton-style performances helped distinguish him from his more reserved co-stars, and won him not only a sizeable youthful following but also some encouragingly positive reviews in the newspapers.21

After the show ended in 1969, Jason went on to appear in a wide range of other productions, including another ITV tea-time comedy show in 1970 entitled Two Ds and a Dog (in which he was reunited with Denise Coffey, playing a couple of eccentrics called Dotty Charles and Dingle Bell who, with their dog Fido, travel around in search of adventures), a short stint in the daily ITV soap Crossroads (playing an increasingly unpredictable gardener), and a few one-off episodes of such shows as Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) and Doctor in the House. He also joined the large team of contributors to the long-running BBC Radio 4 satirical news series Week Ending. Rather more significantly, he was given a regular role – or, more accurately, range of roles – in LWT’s Hark at Barker.

Hark at Barker was a sketch show, running from 1969 to 1970, that first brought Jason into the orbit of Ronnie Barker. Like Jason, Barker had started out in Rep, acquiring his technique and exploring his range by accepting each new weekly challenge as the conveyor belt of productions rolled on. He represented to Jason just how far an actor like him could go in his profession: the rather portly Barker had never been leading man material, but his versatility, intelligence, discipline and wit had enabled him to become a very popular, in-demand and critically admired performer, who was now regarded as a star in his own right. The two men soon saw in each other a kindred spirit, became good friends, and worked extremely well together on the screen.

Encouraged by his association with Barker, Jason then went on to win his own first starring vehicle in the 1974 ITV slapstick-spy spoof The Top Secret Life of Edgar Briggs. Although it was actually a very patchy affair – sometimes inspired, sometimes falling flat – and it struggled to compete for viewers in the ratings, the programme brought him easily the most positive publicity of his career so far, with the Daily Mirror describing him excitedly as ‘the talk of the comedy world’ and quoting his director, Bryan Izzard, as predicting that he ‘is going to be a great star’.22 He followed this in 1976 with another starring vehicle for ITV entitled Lucky Feller, which cast him as a woman-shy man called Shorty Mepstead who was still stuck at home with his mother and his much more confident elder brother, but this programme, too, failed to capture the public’s imagination and faded quietly away after a solitary series.

Here was the nagging problem for David Jason: he was, by this time, sufficiently well known to attract plenty of media attention for his new projects, along with quite a few predictions about his imminent ascension to ‘overnight star’ status, but the projects and promises continued to come and go without that final big breakthrough being made. Indeed, by the middle of the decade, the optimistic articles were already beginning to sound somewhat hollow. His most vocal champions in the press were starting to sound unsure, with The Stage newspaper capturing their growing sense of frustration, disappointment and impatience when it declared: ‘Somewhere there is a writer whose ideas Mr Jason can execute to great effect, but they have not yet met.’23 In a ruthless profession where timing is often thought to be everything, the actor was fast reaching the stage in his career when his image as one of the ‘next big things’ was in serious danger of seeming outdated.

The most significant thing that happened in 1976 was his recruitment, in a supporting rather than a starring role, in a new BBC2 sitcom that reunited him with Ronnie Barker: Open All Hours. Deeply respectful of his more experienced, and more famous, friend and fellow performer, Jason was happy to serve as his sidekick, playing the put-upon and quietly desperate little Granville to Barker’s big, tight-fisted, lustful and stuttering shopkeeper Arkwright. The chemistry between the two performers seemed effortlessly engaging, and the show, gradually attracting more and more viewers, would run on well into the next decade. It added greatly to Jason’s popularity, while seeming to suggest that, by this stage in his career, he had found his level as, to put it bluntly, a superior kind of support act.

Although he continued to be offered, and sometimes accepted, the odd starring role of his own, the moment never seemed right to finally realise his full potential. The most successful of these ventures was almost certainly A Sharp Intake of Breath, which lasted for four series over four years, starting from 1977, on ITV. Playing yet another likeably ‘ordinary’, somewhat whimsical, figure named Peter Barnes (and ably supported by a good cast that included Jacqueline Clarke, Alun Armstrong and Richard Wilson), the show performed very well in the ratings and he received another flurry of favourable reviews, without, once again, threatening to become one of the small screen’s iconic comic figures.

By 1980, therefore, David Jason was in real danger of being pigeonholed, albeit reluctantly, as the nearly man of great British comic acting: the splendid character actor who, due to bad luck rather than lack of talent, had lost out when it came to landing the career-defining roles. He still wanted to break through, and he certainly still deserved to break through, but, to be harshly realistic, time seemed to be fast running out.

Nicholas Lyndhurst, in contrast, had many years ahead to fulfil his own great potential, but he, too, was looking to move on at the start of the new decade. Tall and skinny and aged just nineteen, he was eager for roles that allowed him to be something other, and more, than yet another stereotypical boy or son.

Born in 1961 in Hampshire, Lyndhurst had first stepped on to a stage at the age of six, when he played a donkey in his school’s nativity play (‘My only line was “Hee-Haw . . .”’). Two years later, he started asking his mother if he could go to drama school, and, when he reached the age of ten, his mother relented and he went off to the Corona Stage Academy, in Hammersmith, west London. ‘I was determined to go to this magical place where the teacher was an actor, though I had no concept of what I was aiming for,’ he would later explain. ‘I didn’t believe I’d ever actually open my mouth and have a speaking part in anything. The idea of achieving fame and fortune didn’t cross my mind.’24

Lyndhurst did start to appear in adverts, but this was primarily to pay for his tuition fees. His first ‘proper’ television work came in a couple of BBC Schools productions, followed by a number of peripheral non-speaking roles in a variety of mainstream programmes. His debut in a major production was as Peter in a 1974 BBC adaptation of Heidi, and he followed this a year later by playing Davy Keith in a BBC period drama mini-series called Anne of Avonlea (a sequel to Anne of Green Gables).

It was shortly after this, when Lyndhurst was deemed to have reached that difficult ‘transitional’ phase between juvenile and adult actor, that work started to dry up and his professional future looked uncertain. The only option was to wait and see what, if any, offers arrived, and, fortunately for him, a very exciting one materialised in 1978: the role of Ronnie Barker’s young Cockney son in the post-prison sequel to Porridge, Going Straight. Building on the priceless prime-time exposure that this afforded, he then moved on to win the role of Wendy Craig’s gauche teenaged son Adam in the funny if sometimes rather cloyingly bourgeois Carla Lane sitcom Butterflies.

By 1980, on the verge of his twenties, he had impressed plenty of critics with the breadth of his portrayals, which had stretched all the way from patted and powdered posh fops to gruff and grungy rough scruffs, but he was, in truth, still in danger of being stereotyped – as far as most of the programme makers were concerned – as the short-shelf-life ‘youth’ type. He had reached that point in his career where, even if an ‘older’ role was not yet available, he hoped that at least a better youthful role was open to him that would allow him to settle into the part and start to grow. The range of options, however, seemed slim. All that he could do was wait, and hope, for his best chance to arrive.

The veteran Lennard Pearce, meanwhile, had started 1980 with a nagging feeling of professional ennui. He had been through it all – the highs, the lows, the generosity, the pettiness, the pleasure and the pain, the drama and the dullness of the acting business – and he was finally getting tired of it all. He still loved his profession, he still relished the best roles, but, after several years of being obliged to do little more but go through the motions, he was, by 1980, beginning to feel like calling it quits.

Pearce was born in Paddington, London, in 1915. He was a rather dapper and diligent RADA-trained actor who had also experienced the more fluid and informal atmosphere of the wartime show business community as a member first of ENSA and then of the Combined Services Entertainment touring companies. He followed this in peacetime first with a couple of seasons at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Sheffield, and then a fairly lengthy period based at the Empire Theatre in Peterborough as a member of Harry Hanson’s Court Players (writing a few plays there himself).

A fairly familiar minor figure in West End plays from the early 1960s onwards, he appeared as the Hungarian phonetician Zoltan Karpathy, as well as understudied the role of Alfred P. Doolittle (played by Stanley Holloway), in the original London production of My Fair Lady, before moving on to have spells at the National Theatre under Sir Laurence Olivier and the Royal Shakespeare Company under Trevor Nunn, as well as shorter and less glamorous stints in various repertory companies (where, amongst many other encounters, he met David Jason at Bromley Rep, appearing with him briefly during the mid-1960s in a production of Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals).

Mixing with the likes of such up-and-coming talents as Albert Finney, Derek Jacobi, Maggie Smith and Anthony Hopkins, he contributed – albeit most often in minor roles – to numerous theatrical successes during the best years of his stage career. Pearce never really established himself on television, however, but did appear in the odd minor role in such notable productions as the BBC’s groundbreaking docu-drama Cathy Come Home (1966), as well as one-off episodes of Crown Court, Dixon of Dock Green, Dr Finlay’s Casebook, Play for Today, Coronation Street and Sykes.

Always a heavy smoker, and – as a consequence – having struggled for many years with a weakened voice, he had also started to experience problems relating to balance and concentration while appearing mainly in stage plays during the 1970s, thus shaking his confidence in playing in front of an audience. Over-worked, increasingly worried about how he could make ends meet and now drinking rather heavily, he was at a very low ebb in his life. ‘I hadn’t had a break from acting for 35 years,’ he would later explain. ‘People were trying to evict me from my flat, and I drank a bottle of whisky every night. I looked gaunt – a skeleton, absolutely ghastly.’25 In 1980, after being diagnosed with critical hypertension and put on seven different types of medication for the rest of his life, he turned teetotal and contemplated, at the age of sixty-five, retiring from the profession and leading a much more leisurely existence.

This, then, was where the relevant figures were at the start of the new decade: Sullivan and Butt reeling from the cancellation of their new project, and Jason, Lyndhurst and Pearce dissatisfied, to varying degrees, with the current state of their acting careers. None of them knew it, in the autumn of 1980, but, this time next year, each one of their professional lives would seem much more exciting – and the British sitcom would start seeming genuinely relevant once again.