Читать книгу The History of the Times: The Murdoch Years - Graham Stewart - Страница 10

CHAPTER TWO

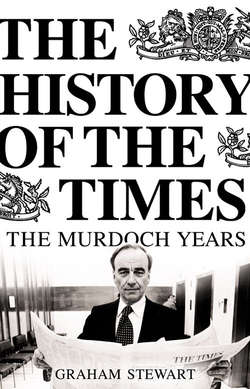

‘THE GREATEST EDITOR IN THE WORLD’

I

ОглавлениеAfter fourteen years in the chair, William Rees-Mogg had made it clear he would relinquish the editorship once the transferral of The Times’s ownership was complete. Thus, the first question facing Rupert Murdoch was whether the new editor should be appointed from inside or outside the paper. It was recognized that existing staff would be happier with ‘one of their own’ taking the helm rather than an outsider who might sport alienating ideas about improving the product. But it was not the journalists who were footing the losses for a paper that, on current performance, was failing commercially. In making his recommendation to The Times’s board of independent national directors, the proprietor had to consider the signal he would be sending out both to the journalists and to the market outside about what sort of paper he wanted by how far he looked beyond the environs of Gray’s Inn Road.

There were three credible internal candidates. As early as 12 February, Hugh Stephenson, the long-serving editor of The Times business news section, had written to Murdoch asking to be considered for the top job.[105] A left-leaning Wykehamist who had been president of the Oxford Union prior to six years in the Foreign Office, Stephenson had been with The Times since 1968. This was an impressive résumé, but not one especially appealing to the new proprietor who was, in any case, not an admirer of the paper’s business content. Even quicker off the blocks was Louis Heren, who had made his intentions known to Sir Denis Hamilton the previous day. He was probably the candidate who wanted the editorship most and his success would certainly have been something of a Fleet Street fairy tale. The son of a Times print worker who had died when his boy was only four, Louis Heren had been born in 1919 and grown up in the poverty of the East End before getting a job as a Times messenger boy. His lucky break had come when an assistant editor noticed him in a corner, quietly reading Conrad’s Nostromo. Subsequently, he was taken on as a reporter and, after war service, he developed into one of the paper’s leading foreign correspondents, sending back dispatches from Middle Eastern battlefronts where the new state of Israel was struggling for its survival, and from the Korean War and later becoming chief Washington correspondent. If not a tale of rags to riches, it was certainly rags to respectability and, as Rees-Mogg’s deputy, he was entitled to expect to be considered seriously. But the fact that he had been, to all intents and purposes, educated by The Times posed questions as to whether he was best able to see the paper’s problems from an outside perspective. He was also sixty-two years old. When he sent the new owner a list of suggested improvements to the paper, Murdoch replied, without much sensitivity, that he wanted an editor ‘who will last at least ten years’ and that another rival for the post, Charles Douglas-Home, ‘is more popular than you’.[106]

On this last point, Murdoch was well informed. Charles Cospatrick Douglas-Home (‘Charlie’ to his friends) was the popular choice, certainly among the senior staff. He was the man Rees-Mogg wanted as his successor and when the outgoing editor asked six of the assistant editors whom they wanted, five of them had opted for Douglas-Home. The chief leader writer, Owen Hickey, had even taken it upon himself to write to Denis Hamilton assuring him that Douglas-Home was the man to pick.[107] At forty-four, he was the right age and since joining The Times from the Daily Express in 1965 he had held many of the important positions within the paper: defence correspondent, features editor, home editor and foreign editor. He had been educated at Eton and served in the Royal Scots Greys. He was the nephew of the former Conservative Prime Minister, Alec Douglas-Home, and his cousin, a childminder at the All England Kindergarten, had recently become engaged to the heir to the throne. So he certainly had highly placed ‘connections’ (a disadvantage in the eyes of those who believed having friends in high places compromised fearless journalism). But ‘Charlie’ was no society cyphen. He took his profession seriously and had well-formed ‘hawkish’ views, especially on defence and foreign policy – all likely to endear him to the new, increasingly right-wing proprietor. He was also something of a contradictory figure: a former army officer who no longer drank, a fearless foxhunter who did not eat meat and a gentleman who, like an ambitious new boy in the Whips’ Office, had once been caught keeping a secret dossier on the private foibles of his colleagues.[108]

Murdoch interviewed the three ‘internal’ candidates on 16 February although, since he already had a preferred candidate in mind, he was essentially going through the motions. The man he wanted was not an old hand of The Times. Having made such a success steering the Sun, Larry Lamb anticipated the call up and was deeply hurt when it did not come. ‘I would never have dreamt of it,’ Murdoch later made clear, ‘he would have been a disaster.’[109] Yet Murdoch’s critics, incredulous that he meant what he said about guaranteeing editorial independence, were still waiting to see which other stooge he would appoint. In an article entitled ‘Into the arms of Count Dracula’, the editor of the New Statesman, Bruce Page, informed his readers, ‘it is believed in the highest reaches of Times Newspapers that the candidate which [sic] he has in mind is Mr Bruce Rothwell. Rothwell can reasonably be described as a trusted Murdoch aide …’[110] But, whatever was now the practice at the New Statesman, The Times was not ready to be run by a man named Bruce. Murdoch had fixed upon someone very different – a hero in liberal media circles.

Even before the deal to buy Times Newspapers was done, Murdoch had invited Harold Evans round to his flat in Eaton Place and asked him whether he would like to edit The Times. It was a probing, perhaps mischievous, question since Evans was at the time still trying to prevent the Murdoch bid for TNL so that his own Sunday Times consortium could succeed. But Murdoch could have been forgiven for regarding the avoidance of saying ‘no’ as a conditional ‘yes’.

Harold Evans was the most celebrated editor in Fleet Street. At a time when standards were said to be falling all over the ‘Street of Shame’, Evans appeared to exemplify all that was best about the public utility of journalism. By 1981, he had been editor of the Sunday Times for fourteen years – thereby shadowing exactly the service record of his opposite number, Rees-Mogg, in the adjoining building at Gray’s Inn Road. The two editors were the same age but their backgrounds could not have been more different. Two years older than Murdoch, Harold Evans was born in 1928, the son of an engine driver. His grandfather was illiterate. Leaving the local school in Manchester at the age of sixteen, he had got his first job towards the end of the Second World War as a £1-a-week reporter on a newspaper in Ashton-under-Lyme. The interruption of national service with the RAF in 1946 led to opportunity: the chance to study at Durham University (where he met his Liverpudlian first wife, Enid) and later Commonwealth Fund Journalism fellowships at the universities of Chicago and Stanford. By 1961 he had become editor of the Northern Echo. Driven by its new editor, the Echo started to take its investigative journalism beyond its Darlington readership. Its campaign to prove the innocence of a Londoner wrongly convicted of murder gained it national prominence. One of those who took notice was the editor of the Sunday Times, Sir Denis Hamilton, who brought Evans down to London to work alongside him. The following year, 1967, he succeeded Hamilton as editor of the paper. It was a meteoric rise from provincial semi-obscurity. Evans immediately proved himself at Gray’s Inn Road. In his new role as editor-in-chief, Sir Denis’s patronage and guidance were useful and some of the paper’s success was the consequence of his own formula: the paper’s colour magazine (a honey pot for advertising) and major book serializations. But Evans built on these strong foundations and, assisted by Bruce Page, Don Berry and others, he entrenched the position of the Sunday Times as Britain’s principal campaigning and investigative newspaper.

In 1972, Evans drove the campaign with which his name, and that of the Sunday Times, will always be associated: the battle to force Distillers Ltd to compensate adequately the victims of its drug, Thalidomide. The immediate reaction – as he well anticipated – was Distillers’ withdrawal of £600,000 worth of advertising in the paper. The other equally swift response was an injunction silencing the Sunday Times’s attempts to reveal the history of the drug’s development and marketing. With great tenacity (and an understanding proprietor in Roy Thomson), Evans continued the fight through the courts and to Strasbourg. Distillers was eventually forced into a £27 million payout to its product’s victims. And at last, in 1977, the Sunday Times got to print the details of its story (although the print unions decided to call a stoppage that day, ensuring few got to read about it).

Under Evans, the Sunday Times was a paper with a liberal conscience. The paper appeared at ease with the more permissive and meritocratic legacy of the 1960s. The cynic within Murdoch may well have thought that he could silence the howls of protest about his being allowed to buy The Times by putting such a respected, independent and liberal-minded editor in charge of it. Indeed, to appoint the man who had spent the previous months trying to wreck the News International bid with his own consortium (and who had privately applauded Aitken’s attack on it in the Commons) appeared to show a spirit of open-minded forgiveness that few had previously associated with Murdoch’s public conduct. Surely the new owner could not be all that right wing or controlling if he put in charge a man who had wanted the Sunday Times to be part owned by that tribune of democratic socialism, the Guardian? This would certainly be a calming message to convey.

But there was genuine admiration as well. Back in 1972, Murdoch had played his part in the Thalidomide controversy. He had been behind the anonymous posters that suddenly appeared across the country ridiculing Distillers, hoping (unsuccessfuly) that by this means his papers could discuss the company’s role at a time when its legal proceedings made doing so contempt of court. Unusually for Fleet Street proprietors, Murdoch understood every aspect of the newspaper business – not just the accounts. Thanks to the efforts of his father and Edward Pickering at the Express, Murdoch could sub articles with effortless aplomb. In this respect, he had something in common with Evans – comprehensive mastery of the journalistic craft. For Evans was the author of such tomes as The Active Newsroom and Editing and Design (in five volumes) which covered almost every aspect of putting together the written (and pictorial) page. The two men also appeared to have a common outlook. They admired American spirit and drive (both later became American citizens) and neither wished to be considered for membership of the traditional British Establishment. Despite his migration to London, Evans still wanted to be considered something of an outsider and this attracted Murdoch. The American academic Martin Wiener had just written his influential book, English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit 1850–1980. Its message appealed to Murdoch who told a luncheon at the Savoy: ‘It is the very simple fact that politicians, bureaucrats, the gentlemanly professionals at the top of the civil service, churchmen, professional men, publicists, Oxbridge and the whole establishment just don’t like commerce.’ Apart from the reference to ‘publicists’, he had basically reeled off a list of the core Times readership. But he was not finished with his castigation: ‘They have produced a defensive and conservative outlook in business which has coalesced with a defensive and conservative trades union structure imposing on Britain a check in industrial growth, a pattern of industrial behaviour suspicious of change – energetic only in keeping things as they are.’[111]

With this attitude, it is easy to see why Murdoch hoped for great things from a restless and meritocratic figure like Harold Evans. That he could be given a pulpit in the housemagazine of the Establishment while being sufficiently intelligent to prevent accusations of being a downmarket influence made him, in Murdoch’s view, the ideal candidate.

It was up to the independent national directors, sitting on the holdings board of Times Newspapers, to make the final decision. The board consisted of four peers of the realm, Lords Roll, Dacre, Greene and Robens who, before ennoblement, had been Eric Roll, civil servant and banker; Hugh Trevor-Roper, historian; Sid Greene of the National Union of Railwaymen; and Alf Robens of the National Coal Board. Two new directors nominated by Murdoch now joined them: Sir Denis Hamilton and Sir Edward Pickering. Hamilton’s appointment was uncontroversial but Dacre objected to Murdoch assuming Pickering would be acceptable without the directors first voting on it. There was an embarrassing delay at the start of the meeting while this was done although it was not entirely to the directors’ credit that they appeared to know little about one of Fleet Street’s most successful editors and longest serving figures.[112] It had been under Pickering’s editorship that the Daily Express had achieved its highest ever circulation. Suitably acquainted with his qualifications, the directors hastily assented to Pickering joining them and proceeded on to the main business – the appointment of the new editor. Under the articles of association, the proprietor had the power of putting forward his preference for editor. The directors had the right of veto but not necessarily the option of discussing who they actually wanted. Had they the right of proposition, the editorship would most likely have gone to Charles Douglas-Home. But it was Harold Evans’s name that Murdoch put before them.

Not everyone shared his enthusiasm. Marmaduke Hussey, the executive vice-chairman of TNL who had overseen the failed shutdown strategy with the unions in 1979–80, had already assured Murdoch that the intention to make Evans editor of The Times and to move his old deputy, Frank Giles, into his vacated chair at the Sunday Times was ‘the quickest way to wreck two marvellous newspapers I can think of!’. To no avail, Hussey pleaded with him to make Douglas-Home the new editor.[113] Having brought Evans to the Sunday Times in the first place and watched over him as group editor-in-chief and TNL chairman, Denis Hamilton was, in principle, well placed to offer his assessment. And it was not entirely favourable. Certainly, Evans had his flashes of inspiration, even genius, but he was temperamental and liable to change his mind. In the course of producing a once weekly product this could be managed, but in editing a daily it could be disastrous. Yet, at the meeting of national directors, Hamilton chose to pull his punches and the opposition to Evans’s appointment was instead led by the forthright historian Lord Dacre, who articulated his objections with a pointed vehemence that bordered upon the abusive. But Dacre’s blackball was not enough and following his departure to deliver a lecture at Oxford, Murdoch’s insistence that The Times needed the best and Evans was the best convinced the rest of the board.[114] So it was that Harold Evans became only the eleventh man to edit The Times since Thomas Barnes established the modern concept of the office in 1816, the year after Waterloo.

Evans’s appointment caused a buzz throughout Fleet Street. Those with a liking for archaic usage may still have referred to the paper as ‘The Thunderer’ but as a noun, not a verb. If anything, critics, particularly those who did not read it, thought of it as The (behind the) Times. Murdoch hoped that the new editor would instil some of the Sunday paper’s drive and contemporary feel into the all too respectable daily.

Those happy with the paper as it was greeted this prospect with disquiet. Louis Heren was of the view that ‘we were not a daily version of the Sunday Times’. But he conceded that the niche was a small one, being ‘boxed in by the Guardian on our left and the Daily Telegraph on our right’ while ‘the FT stood between us and all that lovely advertising in the City of London’.[115] The fact that the paper’s readers were sufficiently loyal to return to it after it had been off the streets for almost a year was not, in itself, proof that all was well. In retrospect, Hugh Stephenson took the view that the 1979–80 shutdown ‘served to make people realize that the things they really missed about The Times were its quirky features – letters, law reports, obits, crossword. They didn’t miss its news, which wasn’t particularly good. In most respects the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian and the Financial Times were better newspapers.’[116] This was an assessment broadly shared by the new editor.[117] In 1981, The Times was normally four pages longer than the Guardian and four pages shorter than the Telegraph. But the gap was wider in the statistics that mattered. In daily sales, the Guardian had overtaken The Times in 1974. Almost since the day of its launch in 1855, the Telegraph had given The Times a pasting. When Evans took over, The Times averaged 282,000 daily sales to the Telegraph’s 1.4 million.

Now the drive was on at least to catch up with the Guardian again. There would be no repeat of the famous 1957 advertising campaign – ‘Top People Take The Times’ a preposterously exclusive slogan for a campaign supposedly intended to widen circulation. Murdoch believed The Times could aim for a half-million readership. Under Hamilton and Evans the Sunday Times, with its book serializations and glossy colour magazine, had promoted the new elite of the photogenic. It was as glamorous and of the moment as The Times was monochrome and old-fashioned. Evans’s Sunday Times promoted celebrities and ‘big names’ while the Times old guard were still lamenting the loss of the anonymous non-de-plume ‘By Our Special Correspondent’. Sunday Times reporters having occasion to cross the Gray’s Inn Road connecting bridge that took them into The Times claimed to feel they were crossing into East Berlin.

The Times old guard – those horrified by the connotations of the word ‘promotion’ and ill at ease with the world of the colour supplement – hated the prospect of their paper being turned into a daily Sunday Times or a mark two Telegraph. They and their spiritual forebears had blocked a 1958 report by the accountants Coopers with its outlandish idea about putting news on the front page (as the Guardian had done since 1952), their objections only finally overcome in 1966. Nor did they see what was wrong with a relatively low circulation so long as it was sufficiently upmarket to cover its costs through advertising (as the FT did). There was certainly no obvious link between a broadsheet’s influence and its sales figures: by the late 1930s, the Telegraph had opened up a half-million lead on The Times, but it was Geoffrey Dawson who was the politically influential editor, not the Telegraph’s Arthur Watson.

Those apprehensive about the forthcoming Evans – Murdoch strategy of going for growth could also point to precedent. Fortified by Thomson’s cash injection, Rees-Mogg’s editorship had started with radical attempts to modernize the paper by introducing a separate business news section, a roving ‘News Team’ acting like a rapid reaction force under Michael Cudlipp’s direction, bigger headlines and shorter sentences. Circulation had improved dramatically from 280,000 in 1966 to 430,000 in 1969. Meeting in the White Swan pub, twenty-nine members of staff, including the young Charles Douglas-Home and Brian MacArthur, had signed a declaration condemning what they believed was the accompanying cheapening of the paper’s authority. But the most telling argument was that the paper was still not making a profit – the boosted revenue from sales being outstripped by the cost of the expansion programme necessary to sustain it. So the expansion policy was abandoned; circulation slipped back towards 300,000 and, by the mid-seventies the paper even – fleetingly – returned a profit.

Now the introduction of a Sunday Times man at the helm suggested The Times would retrace its steps and repeat the failed 1967–9 growth strategy, but Harold Evans saw his task as editor in less primarily commercial terms. ‘At the Sunday Times before Hamilton and Thomson,’ he later recalled, ‘it was a sackable offence to provoke a solicitor’s letter,’ but after he became editor ‘we were in the Law Courts so many times I felt they owed me an honorary wig.’ Evans maintained that this became necessary ‘because real reporting ran into extensions of corporate and executive power that had gone undetected, hence unchallenged, and the courts, uninhibited by a Bill of Rights, had given property rights priority over personal rights.’[118] This had not been how The Times had generally seen its role during the same period. Indeed, when in 1969 the paper caught out Metropolitan policemen in a bribery sting some old Times hands were deeply uneasy about their paper going in for the sort of exposé that subverted the good name of the forces of law and order. Others agreed. Three days after the story broke, the paper reported on its front page a meeting of Edward Heath’s Shadow Cabinet in which ‘it was considered deeply disturbing that to trial by television … there might now be added trial by newspaper, with The Times leading the way … It was agreed that The Times appeared to have put the printing of allegations against the police above the national interest.’[119]

With Evans’s arrival, it seemed The Times would become a disruptive influence again. The new editor proposed what he called ‘vertical journalism’ as opposed to the ‘horizontal school of journalism’ with which the paper had become too comfy, whereby ‘speeches, reports and ceremonials occur and they are rendered into words in print along a straight assemblyline. Scandal and injustice go unremarked unless someone else discovers them.’ Evans believed he was the true inheritor of an older Times tradition, ‘The Thunderer’ of Thomas Barnes, in which ‘the effort to get to the bottom of things, which is the aspiration of the vertical school of journalism, cannot be indiscriminate. Judgments have to be made about what is important; they are moral judgments. The vertical school is active. It sets its own agenda; it is not afraid of the word “campaign”.’[120]

Evans’s style of leadership was markedly different from that of Rees-Mogg. The outgoing editor had always given the impression that it was the paper’s commentary on events that was his prime interest. The leader articles written, he was quite content to leave the office shortly after 7 p.m. in order to spend the evening with his family or at official functions and dinners, confident that the team on the ‘backbench’ could be entrusted with presenting the breaking news stories. Evans could not have been more different. On his first day as editor, he told his staff that he would be on the backbench every night. ‘It is called,’ he said proudly, ‘the editing theory of maximum irritation.’[121] And he was not wrong. As if to make his point, he took off his jacket – a sight unseen during Rees-Mogg’s fourteen years in the chair (unfortunately Evans’s unattended jacket was promptly stolen).[122]

One who lamented the passing of the baton from Rees-Mogg to Evans was Auberon Waugh. He foresaw what might be in store:

If, in the months that follow, footling diagrams or ‘graphics’ begin to appear illustrating how the hostages walked off their aeroplane into a reception centre; profiles of leading hairdressers suddenly break on page 12; inquiries into the safety of some patent medicine replace Philip Howard’s ruminations on the English language; if a cheap, flip radicalism replaces Mr Rees-Mogg’s carefully argued honourable conservatism and nasty, gritty English creeps into the leader columns where once his sonorous phrases basked and played in the sun; if it begins to seem that one more beleaguered outpost has fallen to the barbarians, we should reflect that there never really was an England which spoke in this language of good nature, of friendliness, of fair dealing, of balance. It was all a product of Mr Rees-Mogg’s beautiful mind.[123]

105

Hugh Stephenson to Denis Hamilton, 13 February 1981, Hamilton Papers 9383/12.

106

Quoted in Michael Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 203.

107

Owen Hickey to Denis Hamilton, 11 February 1981, Hamilton Papers 9383/12.

108

John Grigg, The History of The Times, vol. VI: The Thomson Years, p. 376; Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 201.

109

Rupert Murdoch to the author, interview, 4 August 2003.

110

Bruce Page, ‘Into the arms of Count Dracula’, New Statesman, 30 January 1981.

111

Rupert Murdoch to the annual lunch of the Advertising Association, quoted in TNL News, April 1981.

112

Richard Searby to the author, interview, 11 June 2002; Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, pp. 204–5.

113

Marmaduke Hussey, Chance Governs All, p. 179.

114

Sir Edward Pickering to the author and Richard Searby to the author, 11 June 2002; Rupert Murdoch to the author, 4 August 2003; Denis Hamilton, Editor-in-Chief, p. 181; Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 205.

115

Louis Heren, February 1981, Quarterly of the Commonwealth Press Union.

116

Hugh Stephenson, ‘Not the age of The Times’, New Statesman, 11 January 1985.

117

Harold Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, pp. 188–9.

118

Evans in British Journalism Review, vol. 13, no. 4, 2002.

119

Michael Leapman, Treacherous Estate, 1992, p. 51.

120

Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, p. 340.

121

TNL News, April 1981.

122

Spectator, 20 June 1981.

123

Ibid., 28 February 1981.