Читать книгу War Party - Greg Ardé - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

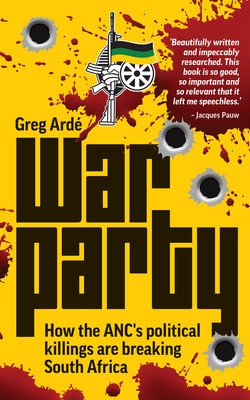

Introduction

ОглавлениеShe crouched over the stream, a baby tied to her back. It was eerily quiet given the circumstances. She was a young woman, probably my age at the time, in her mid-twenties. She splashed water over an aluminium pan, the rinse being the finale in a mundane daily ritual performed by thousands of poor women across South Africa. But her fastidiousness struck me. The water was barely a trickle and the ground around her was stained with blood.

I had stumbled through a field a few minutes earlier, following the hiss and crackle of police radios. I wasn’t sure if she had noticed me. Quite likely not. For the most part, she kept her head down. Somehow we existed for a few minutes in a curious bubble of silence amid the mayhem. When she shifted once or twice to readjust the bundle on her back, her face remained impassive, perhaps quietly determined. That was my take anyway.

I was transfixed. It was early in the morning. I had a sling bag over my shoulder and a reporter’s notebook and pen in my hand. I was there to cover another political massacre. This one was no more or less horrific than the last, but, like other journalists, I had made this my beat so I needed to be there.

By then I had become largely desensitised. The violence was ghastly. But there were only so many moving victim tales the newspaper was interested in, no matter how empathetically and descriptively you told them. Each of the thousands of politically attributed murders was a tragedy, but the appetite for the stories was waning and reporting on them became a body count.

Journalists darted around KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) to places like Bhambayi fresh after the kill, looking for new angles. The young woman at the stream was my angle, but I stood there mute, trying to take it all in. Over 200 people had been murdered in Bhambayi in the preceding year in clashes between African National Congress (ANC) and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) supporters. I think this massacre took place in August 1993, though I now can’t be sure. It might have been September. Online references point to 9 murders in August and 22 in September in Bhambayi alone.

The woman beside the stream was a poignant picture of solitude, like those statues that survived intact after cathedrals and churches were bombed to smithereens during the Second World War. Not far away from her, bodies lay twisted and hacked, dead eyes staring vacantly into the sky. It was a maelstrom of misery.

Early in the morning men full of bloodlust had gone on a rampage of unimaginable terror. And there she was a few hours later, bent over the stream washing her pan. In that routine chore, she was trying to cling to life. It was all she could do amid the horror: salvage what little dignity she could in Bhambayi.

That such bloodletting happened there in that place is deeply ironic. Bhambayi borders on the settlement of Phoenix, which was founded by Mahatma Gandhi in 1904. Here he spent most of his South African years, sowing the seeds for his philosophy of Satyagraha, or non-violent resistance to evil. Bhambayi is a Zulu approximation of “Bombay”.

A museum at Gandhi’s settlement celebrates the fascinating historical nexus which the place represents. A few kilometres up the road is Inanda, which birthed John Langalibalele Dube and his nephew Pixley Seme, both of whom helped found the ANC, now South Africa’s ruling party. There are reports too that anti-apartheid activists Steve Biko and Rick Turner both spent time at the Phoenix settlement next to Bhambayi.

In 1994, when Nelson Mandela cast his first vote as a free man, it was up the road at Ohlange High School, founded by Dube. I was there when Madiba voted, little realising the historic day would not put an end to the ongoing violence which had erupted between the ANC and the IFP during the transition to democracy. In a bid to end these bloody battles, Mandela, speaking at a massive rally in Durban, called on his followers to throw their weapons into the sea.

The gathering at Kings Park Stadium was a spectacle. Thousands of ANC members arrived decked out in traditional regalia, the hallmarks of a Zulu show of power: skins, shields and knobkieries. Mandela’s peace plea was powerful but it didn’t end the killings. The violence so vexed the president that he made a special journey to Zulu king Goodwill Zwelithini’s palace in Nongoma in 1996. In February of that year alone, 60 people were murdered in KZN.

Mandela emerged from the royal meeting visibly perturbed and addressed an impromptu press conference. He put on a brave face but he looked quite helpless. Again, trying to get a new angle I pressed him about his concern. His answer has stayed with me because it spoke to the human degradation of violence. There is no dignity in this, he said. “We cannot let … people be humiliated by this killing.”

By the late 1990s the KZN killings had slowed to a trickle after the gruesome flood that had gone before. Then it started up again, but this time it wasn’t the wholesale slaughter that had characterised the ANC–IFP conflict. Mass murder morphed into targeted assassinations.

By 2016 the KZN government, probably unsure of what to do, appointed a commission of inquiry to probe the hundreds of political hits that have taken place in the province. Like that of many others, the commission’s report will probably gather dust in a government office somewhere – tragically – because it is a chilling indictment of the ruling ANC and the mafia-style politics the party has incubated in KZN and which is spilling beyond the province’s borders. It threatens to be the harbinger of a fully fledged gangster state where might is right and the big guns call the shots.

I don’t have an intimate understanding of the ANC or its broedertwis, nor do I regard this book as political analysis of any heft. But, working in KZN, I have seen a story unfold. It is about how greed shatters ordinary lives and is robbing South Africans of dignity. The ANC’s policy of cadre deployment has created a depraved, venal monster, a vortex of competing patronage networks. Comrades are killing each other for a place at the trough, for jobs, tenders and contracts.

Lurking behind this monster is a breed of hitmen, or izinkabi, hatched largely by the powerful taxi industry, which offers the perfect cover for killings. The industry is awash with cash, guns and killers, and it moves them around effortlessly. As a result South Africa is developing what the academic Paulus Zulu has described as a “culture of blood” fed by greed, which prizes money over human life.

In KZN murder is increasingly the currency of power. And it is spreading to the other provinces. The capture and evisceration of the police, crime intelligence and prosecutorial authorities have helped spread the killing network. The state has found itself largely powerless against the entrenched strongmen.

In South Africa today, everything seems to be about the party and the spoils of war. The ANC, the party of liberation, is becoming a war party.