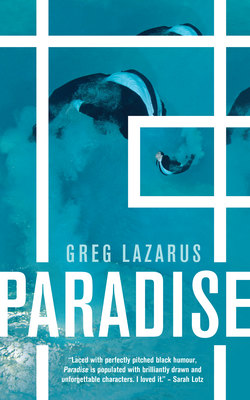

Читать книгу Paradise - Greg Fried - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Maja

ОглавлениеMaja Jellema lay in bed alongside Jerome, examining her print of Hunters in the Snow. The Brueghel picture – the only remnant of her childhood, now spotted and discoloured in the corners – hung on the facing wall. She was imagining making her way home through the snow with those hunters and their dogs, down into the valley with a spear resting on her shoulder.

Jerome, warm and unshaven, rolled over and curled a few strands of her long red hair around his finger. “Look.” He tented the duvet for her to gaze beneath. “Someone’s happy to see you.”

“We’ll have to save the happiness for later,” she said, touching his cheek. “I’ve got to get to work.”

Ignoring his sigh, she got out of bed, turned the radiator knob as high as it would go and went to make coffee.

The bubbles rose through the glowing water of the glass kettle, illuminated by a blue light-strip that curved around the base. Besides the Brueghel print, this was her favourite object in the apartment, a device that feverishly did her bidding every morning. As she watched the fluttering parcels of air rise through the fluorescent water, Jerome squeezed past her into the bathroom, giving her bare thigh a passing pat. Maja hoped one day for a bigger bathroom. Also a kitchen that was more than a bar fridge, gas ring and shelf in the corner of the bedroom. She’d chosen the place in a hurry, when she’d wanted something cheap and far away from bad memories. The money situation had never much improved, and she hadn’t moved.

Her fling with Jerome had begun at Het Nieuwe Jeruzalem, where Maja waitressed. Jerome had wandered in one day two months back, a storm approaching, the door banging his arrival. “Jezus, man, it’s windy out there,” he’d said, removing his duffel jacket and sweater and picking a table next to the window.

The owner, a cadaverous man with dandruff flecks on the collars of his ancient jackets, kept the place hot; he told Maja it encouraged patrons to stay longer. She’d been working there for years, but he still seemed uneasy when she came close; his moustache twitched. Maja suspected that he regretted his Christian charity in hiring her. Het Nieuwe Jeruzalem had been the only place willing to take her on.

Maja handed the menu to this new customer: a big, good-looking young fellow, more robust than their usual clientele. Through the window, the sky was low and grey, people walking along Hemonystraat with heads bowed against the cold gusts. “Like on a ship,” he said, following her gaze. There was a tattoo up his arm, a serpent. Its green tail dangled down his forearm, tip nestling between his index and middle fingers. The serpent slithered under the edge of his black T-shirt. Right then she wanted to sleep with him, if only to see where the snake ended.

Now, with the bathroom door open, she could see the blurred serpent being assaulted by hot water in the shower. She’d come to know the tattoo, her fingers tracing its length up his meaty pectoral to the fangs that rested on his shoulder blade. The tattoo marked Jerome’s two years on a merchant vessel as a teenager, and also honoured his father and grandfather, both sailors. Maja saw an ancient sea creature that had washed up on the shore of the twenty-first century, clinging to a modern-day predator.

He was saying something, half-lost in the rustling of the shower curtain as he turned off the water and stepped out.

“What was that?” she asked.

“Pieter said yes.” Jerome was briskly rubbing himself dry.

“Why didn’t you tell me last night? What did he say?”

“No, you have to leave for work,” he said teasingly. “We can talk later. I understand, you’ve got a high-pressure job – no time now.” He always got a little sensitive when she refused his advances.

Maja glanced at her watch. The restaurant could wait. The owner was frequently late, plagued by allergies. If allergies were an excuse, so were opportunities. She watched Jerome as he dried himself meticulously, then took his clothes from a hanger on the hook behind the door and dressed, clearly enjoying tormenting her.

“Okay, I’m sorry about saving the happiness for later,” she said. “I’m a bitch in the morning sometimes, sure. Now can you tell me?”

“Pieter’s got something for you.” Jerome finished buttoning his white Oxford shirt and began to knot his silk tie in the mirror. Pieter was demanding about appearance.

Maja had met Jerome’s boss only once, at one of his clubs. She and Jerome had eaten with Pieter and a sullen Surinamese woman he clearly hadn’t chosen for her brains. They’d sat around a fake-marble table, its creamy, veined surface held aloft by four stone cherubs. High on the walls of the club were painted tiers of cheering spectators in togas, raising their fists as they looked down at the dancers and drinkers, tourists and schemers who thronged the floor. Maja had made fun of the club to Jerome afterwards, but she liked Pieter: blonde and green-eyed, full of friendliness and charm, a good listener and teller of stories. Presumably he kept different manners for other occasions.

“May I say,” Jerome remarked as she watched him, “you look good in just a T-shirt. You’re an attractive woman. Like a flame.”

“A pale flame. But thank you. You’re not so bad yourself. So what does Pieter have for me? What’s the plan? He knows I’m good at museum work – you told him that?”

Jerome finished combing his hair. “It’s not in a museum. Not even in Amsterdam.” He slapped cologne on his rosy cheeks. “South Africa. Pieter has a few friends in Cape Town – useful place for passing things through.”

It would be, thought Maja: like a straw at the bottom of Africa, a city for sucking out guns, drugs, women, or blowing them in.

“So they’ve put him onto something,” Jerome continued. “Someone there who can’t keep his mouth shut.”

The ultimate sin. Maja herself had been good at keeping her mouth shut, in the long-gone days. “What is it?”

Jerome shrugged. “Need-to-know basis – that’s how Pieter does it. You don’t know, you can’t talk. But it’s worth a bit to him.”

“How much?”

“Hundred thousand euro. Ten per cent to me, you keep the rest.”

Five years’ salary at the Jeruzalem.

Maja had promised herself years ago that nothing would draw her into that world again. But with Carel’s mess, what was her alternative? That was life: choosing between bad options. And she was tired of having no money. She went to the snuffbox on her side of the bed, took a pinch, sniffed. Her father had taught her how to do it. The box, the only thing she had of his, was beautifully carved: a snake entwined around a tree. She passed it to Jerome, who took a little and sneezed.

“New?” he asked.

“Yeah.”

“Toasty.”

“It’s drier than the old kind.”

“A lady of taste.” Jerome passed her the box.

“Cash upfront?”

“You crazy? You do the job, you get the cash.”

“Half upfront?”

“Maybe some expenses. You’re not established, it’s on spec. Pieter’s not made of money, you know.” Jerome sounded affronted on his boss’s behalf. In a sense, though, Pieter was made of money. He was a boss, constituted by greed, pride, courage, ruthlessness – and money. “I might be able to get you a thousand.”

“It’s not enough.”

Jerome looked at her closely. “You don’t bargain with Pieter – do it or don’t.”

Maja considered arguing, thought better of it. “I’ll do it.”

“My kind of woman,” said Jerome.

In fact, she was not. She was a dozen years older, much more intelligent, not as good-looking. But she nodded.

“When will you be ready?” he asked.

“What, do you expect me to go buy a new dress or something? Give me the money and the ticket, and I’m all set.”

The morning of Maja’s flight, she left her apartment for a brisk walk along the canal. Her bag was packed; she was keyed up, wanting to leave. There was ice on the ground and the weather was the coldest it had been for weeks. Sometimes, when she looked at Hunters in the Snow in the morning, the wind attacking the window, she thought, you think you’ve got it bad, you in there? Well, look here. Five centuries later, same story.

A strange thing happened at the end of her walk, as she was about to cross the road and climb the three stories to her apartment. She was stretching her calves when a seagull swooped down and loitered a few feet away. As Maja walked towards her building, the seagull rose and flew directly at her face. She saw its black eyes and thin, sharp beak, shouted “Weg !” and swiped her arm in its direction. But a few seconds later it dived again, turned back only by the violent flap of her hand.

Back inside, she looked out of her window onto the canal and saw that the seagull was still there, patrolling the edge.

Her father had loved seagulls. He used to take her on the train to Zandvoort for ice cream and to feed the gulls. He liked the way they pecked at each other to get to the crumbs. Tough birds. Maja was no believer in the supernatural, but the stupid thought came that this might be a message from him: Come on, look sharp. Showtime.