Читать книгу I Am Nobody - Greg Gilhooly - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

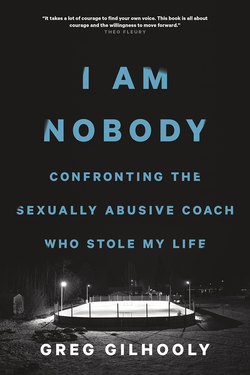

I AM NOBODY

I’M STANDING IN the parking lot of a local community hockey arena. The rink—plain, rectangular, designed like an industrial warehouse—could be anywhere. It’s a cool, still, gray day in the middle of a Canadian winter, snow gently falling, the type of day where every kid should be outside skating and playing, living life to its fullest. It makes me think back to all the hours we spent playing hockey outside, how good it felt to skate with the wind at our backs, how brutally awful it was to have to turn around and skate back into it. In an instant I am again feeling that cold air biting through my equipment, I am remembering how it felt to freeze into my own sweat. For a moment it’s real, and I want to fall back into it, I want to give myself completely over to the memory of the sound of our skates squeaking as we stood and rocked back and forth in the intense cold, listening while our coaches set out the next drill. I want to be that kid again, getting ready for the next drill while sniffling back a runny nose in the thick fog of our heavy breathing, all of us needing to start moving again to generate some body heat. I can even smell the hot chocolate that was always served to us when we were very young and came inside after our battle with the elements, the true victors being those who could get their skates off quickest and be the first to grab the hot water bottles to warm their frozen feet.

But I’m not a kid anymore, and the game left me with other memories, too.

I enter the arena. I see people milling about, kids dragging equipment bags bigger than the bags I took with me when I went away to university. The scene is chaotic. The arena, like most others, is crowded, not designed for the crush of people. There are children and adults everywhere. And then it starts, something that always happens to me whenever I am at a rink (or in any public space, for that matter). I start scanning the room looking at every adult male trying to figure out why each one is there in the midst of the kids. That one in the corner—is he a parent? Have I seen him before? What is that guy doing over there? Are those kids by the door being watched by their parents? That coach kidding around with the kids on his team—is that normal, or is he getting a little too personal with some of them?

Ten steps later and it has passed. I’ve made it into the dressing room of the team that I coach and all is well. Just the hockey team enters, the boys and the other coaches. Here we can all have fun and the kids can revel in the pure joy of playing hockey. That world out there, the big scary one we all encounter daily, that world doesn’t exist in the energetic lead-up to going out on the ice and playing. On the ice, the kids do things with such speed and grace that you sometimes have to remind yourself just how young they are. Here, one thing and only one thing matters to them: hockey. When they are at the rink hockey becomes their entire world. There is no school, no homework, just a safe place where they can push themselves athletically and at the same time play.

At least, it’s supposed to be safe.

I loved hockey. I still do. Hockey was where I was most comfortable. On the ice I felt completely in control of everything around me. I excelled at hockey and was confident in a way I never was anyplace else. I saw the game and understood its patterns. I was a part of teams and understood the internal dynamics of how teams operated. I could see who was struggling, who needed to work harder, who needed to be pushed, who needed to be supported. It all just came naturally to me. I was at peace in my hockey equipment—the world made sense, I had an identity, and I was proud.

But then, in 1979, when I was fourteen years old, I met Graham James, the once-prominent, celebrated hockey coach. Graham groomed me and then sexually assaulted me over a period of several years into the early 1980s. That changed the way I would see hockey, the way I would see life, forever.

Books like this are usually written by people who are “somebodies”—celebrities, athletes, prominent business people, politicians, or other persons of note. They have a built-in audience, and their views are accorded greater weight and importance than those of a nobody. That makes sense, because as much as the media (and those who sell books) love a good story, those stories need an audience.

But I am nobody, just a victim (or survivor, if you prefer that word, and I understand why many do). I’m not a former professional hockey player, nor was I ever that close to being one. I’m not a “woulda, coulda, shoulda” type who can’t get over the fact that but for this or that I might have been a star. All one can ever know is who I once was, who I became during and after the abuse, and who I am now. I’m just me, once a young boy with promise who had the misfortune of crossing paths with, and then drawing the attention of, a serial sexual predator. Now I am a man who is, decades later, finally putting his life into place.

Because I’m a nobody, you have no connection to me. You don’t know me, so you don’t bring with you any preconceived notions of who I once was, who I am now, and what my struggle did to me. You have no particular reason to care one way or another about me. You haven’t compartmentalized me in any way as somebody you see in the media, in the headlines, on the screens. I’m completely removed from your world while still being a part of it. There is distance between us.

But I could be somebody right next door. I could be the kid from around the corner, the one you used to see playing on your street but who you never really knew. I could be anybody you see when you look out your window. What happened to me could have happened to anybody around you. Maybe it happened to you. And that’s what makes this a horror story, because child sexual abuse happens far more than most people realize. It happens in places where most would never believe it possible, and it is committed by people you would never believe capable of committing such a heinous act.

Most people around me know nothing of the real me, the one I have hidden for far too long. I promised myself when I set out to write this book that I would not gloss over how bad things got or the living hell that sexual assault inflicts on its victims. I promised myself that I wouldn’t make myself out to be stronger than I was and that I would explain that survival and recovery are not always easy or even possible. I promised myself that I would show just how awful abuse can be as I try to come to grips with it and its impact, accepting the past for what it is, and moving forward with recovery. Anything less, any sanitized version of things, would disrespect anybody else who has suffered sexual abuse. Anything less could lead those who are dealing with the same things I am to conclude that there must be something wrong with them, to ask, “Why isn’t he having the same trouble I am having? Why isn’t he facing the difficulties that I am? What about these things that I have to do to try to protect myself that seem to be nowhere on his radar?” I hope that by being completely honest about my struggles I can show others who may be dealing with the same things that they are not alone in their efforts to survive, to find meaning in life, and to flourish while showing the full horror of sexual abuse and its long-term impact.

Still, even after all of these years, after years and years of therapy, I don’t really get it. None of it ever really makes sense.

We all live with our inner voice, the one that is always with us. It is the voice from which we cannot run, the constant in our life that brings us back to our reality, no matter how good we may try to make things look to others in our social media postings, in our daily lives with our smiles and our banter, in our routine comings and goings. Our inner voice does not express an objective truth but rather the way we see ourselves in our world. My inner voice has tormented me:

Why did this happen?

How did it happen?

Who were you?

Who are you?

I can try to explain it, but deep down I just don’t know. I can say all the words, but they are empty, meaningless attempts at ascribing reason to something so outside the realm of what could even be contemplated as a remotely reasonable experience. And that’s what makes all of this so difficult to live with. That’s what makes his abusing me so horrific to me. I don’t understand how it happened to me. I may never be able to understand and accept to my core what happened, why it happened, and how it happened. I understand at an intellectual level how a victim can become powerless and succumb to a predator, but I still do not fully accept that it could have happened to me, that it did happen to me.

Writing this book has been tough for me. I had to revisit how Graham got to me, controlled me, made me do things I didn’t want to do. I have to admit and accept that he was able to get at me, defeat me, tear me apart physically and mentally, rip the life out of me. Everything in my recovery has been about taking back my life, asserting my power and control over who I am and what I will be. Stepping back into my past to write this book was to relive my destruction. Yet in doing so I somehow found my voice, I managed to better understand and accept what had happened, and am better and stronger for having done so.

I am nobody important, nobody of note. I’m just a nobody who was sexually abused by that once-prominent hockey coach, a nobody who because of the abuse actually became nobody at all and believed that I deserved everything that had happened to me, that I deserved to fail at everything in life, that I deserved to be shunned, that I deserved to die.

Except I am still here.

This is my story.