Читать книгу Highballer - Greg Nolan - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

The Rookie

ОглавлениеIt’s mid-April. You’re in a tent perched on the top of a hill overlooking camp. You’re reluctant to leave the warmth of your sleeping bag, especially this early in the season when everything is coated in a thick layer of frost. Even the inside of your tent and the exterior of your sleeping bag are colonized by a thin layer of ice crystals.

Courage attained, you shed the insulation of your down-filled cocoon, pulling cold, damp work clothes over your goosebump-raised skin. You crawl on your hands and knees to the front of your tent and unzip the nylon flap that functions as a door—no matter how you approach this simple task, it’s a zipper that always seems to stick.

You’re on full display, at least that’s how it seems as you stumble outside and confront the elements. Slowly pulling yourself upright, your joints and vertebrae creak and snap, a reminder that you may not be as invulnerable as you once thought. Shivering, you face the frigid landscape, and the first rays of light emerging from the distant eastern horizon hold your attention, but only for a second or two, even though you’ve tuned your senses to be on alert for these moments of extraordinary beauty—a mere snapshot will have to suffice.

You tentatively make your way toward camp, periodically stretching your stiff quadriceps and hamstrings as you advance. The frigid ground crunches under the weight of your boots, and as you draw closer to the Quonset hut, reggae music suffuses the air, as does the bustle of an anxious crew milling about inside. Pulling the canvas flap open to the dining tent, you’re immediately hit by a blast of warm air from a cedar fire burning inside the airtight wood stove. All around, a swirling mass of hippy treeplanters, vying for position at the lunch table and breakfast counter, are fixated on securing their nutritional needs for the day. It’s an important task. Merging into the chaos, you fill your mug with hot coffee and brown-bag whatever is leftover from the feeding frenzy. You then plop yourself down on one of the empty chairs in front of the wood stove. As you try to choke down a few morsels of breakfast—you’re not used to eating this early in the morning—you lean back in your chair and reflect on the day ahead. You have a few minutes to think.

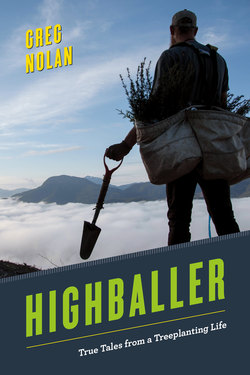

You think about your reputation as a “highballer,” how you’ll soon be forced to throw your body in motion, expending more physical energy in a single eight-hour day than most people will in an entire week. The thought is intimidating, but you pretend to be at peace with it. You think about the drive to work, the ruts in the road and the lousy suspension on the truck you’ll be forced to ride in. You think about the vapid conversation you’ll have to endure in the cab of the truck along the way (you remind yourself to change the batteries in your Walkman, just in case). You think about arriving at your cutblock and being unceremoniously dumped at the bottom of your area, back into the cold morning air. You think about pulling back the tarp covering your tree cache and shattering that thin layer of ice that will have formed on the tops of the seedling boxes overnight. You think about the bitterly cold bundles of trees that lie underneath—you can already feel the icy bite on the tips of your fingers. You think about stuffing your treeplanting bags full of seedlings, stuffing them to the point of bursting. You think about your shoulders and hips straining under the weight of your bags as you pivot to face the mountain that rises before you—it’s some five hundred metres, a single line of 150 trees to the top. You think about those first few shaky steps on broken terrain, poking through the debris on the surface of the ground with your shovel, attempting to home in on good soil. You think about that first tree—it’s a grunt, but it’s finally in the ground. You think about how you’ll be required to repeat the same task, again and again, at least two thousand more times before your day is done. You think about the madness behind such an endeavour.

Several blasts from a truck horn snap you back into the moment, back into the here and now. You think about how you have less than five minutes remaining to enjoy the rest of your coffee in the warmth of the wood stove. It’s nearly 7:00 a.m. The trucks leave at 7:00 sharp. As you step outside, back into the icy early morning air, and begin organizing your gear, the smell of truck exhaust tags your senses. It’s time. It’s time to hit the slopes.

This scene, with variations according to season and locale, was my daily reality for twenty-seven years, between the ages of nineteen and forty-five, beginning in 1983, when I was a hardcore British Columbian treeplanter. It was an exciting, exhilarating period of my life and I embraced the subculture enthusiastically, becoming a top producer, known in the trade as a highballer.1 Looking back now, from sedentary middle age, I remember my early days of treeplanting as a kind of charmed existence, bound up in the glories of my youth, whereas in reality the times of triumph and joy were more than balanced by times of trial and even terror. But it was seldom dull, especially at first when I had the normal youthful doubts about being able to cut it on my first real job. I remember that first day so well.

Barrett Jardine was my sister Lina’s partner. He was a treeplanting contractor. He was the man behind CRC Ltd. I would soon come to appreciate that Barrett’s company was at the very top of the heap in the silviculture arena. It was the company to work for if you were an experienced treeplanter in BC. It had a waiting list with hundreds of names, and the reason for this enviable distinction: working for Barrett was not only lucrative, it was a total fucking blast.

Barrett picked his crews carefully, with an eye for physical prowess, character and, perhaps unintentionally, beauty—at least so it seemed to my adolescent eyes on first viewing the women I was to share camp with. Barrett recruited what struck me at the time as a very satisfactory balance between men and women. I wasn’t expecting this. Barrett also chose his projects carefully, preferring remote contracts—those well off the beaten path—over those within hailing distance of paved roads and fast-food drive-thrus.

These remote and geographically isolated projects fetched significantly higher premiums due to their technical nature and complex logistics. Very few contractors possessed the skill set to pull them off. Of course the geographic isolation presented a host of other challenges, some of which made life difficult for a treeplanter, some of which added an element of risk, all of which generated heightened levels of adventure.

It had taken some serious arm-twisting on my sister’s part to convince Barrett to take me on as a rookie treeplanter. He resisted at first. We had never met. I’m sure he imagined the worst, thinking I was some hapless city punk completely lacking in wilderness skills—some insufferable putz who would become an instant liability to him and to his finely tuned crew. But my sister knew how to apply pressure. Barrett finally relented. My name was added to the crew list, reluctantly.

Barrett didn’t know, but he could have picked a worse candidate for the small rookie training crew he was assembling. I was athletic. I loved the outdoors. I craved adventure. I also hated school, even though I was surrounded by academically oriented siblings. I wanted nothing to do with post-secondary education—something every treeplanting contractor likes to hear. I was a nineteen-year-old boy, the youngest in a litter of five, who was determined to follow a decidedly different path from that of his studious older siblings. I suppose it was partially out of spite that I arrived at this decision.

I trained hard for several months prior to meeting Barrett. I ran daily. I hiked. I lifted weights and I cross-country skied. I had also meticulously assembled my gear for this three-month wilderness gig, scouring every outdoor store, army surplus and second-hand shop for gear, clothing and equipment. Our basement took on the appearance of a marshalling station for a major expedition. My mom, impressed with her baby boy’s zeal, actually ran guided tours through the basement whenever she had friends over. Every time I added to my stockpile, I ran a formal inventory check, complete with clipboard, felt marker and highlighter. I guess I was a little gung-ho.

In hindsight I suppose Barrett’s first impression of me wasn’t exactly confidence inspiring. Not owning a vehicle, and having a mother who had a difficult time letting go, I agreed to let her drive me the seven hundred and fifty kilometres to our designated meeting place at a small café near Purden Lake, BC. I was on pins and needles for the entire journey.

It was my mom who broke the ice on that first day.

She was a character. The only girl among five siblings, she’d led a life of slave labour on the family farm from the moment she was able to walk. Thrown out of the house in her mid-teens, she would later discover that her four younger brothers, the boys she helped raise, had colluded to cut her out of the family fortune (this is how it was explained to me). This not only deprived her of a better life, it shredded her sense of self-worth. She wore this humility, anger and sadness around her like a veil. Barely a day went by when she didn’t reflect on this act of betrayal in some way. Human nature being the mystery it is, this brittle side of her personality was reserved mainly for the benefit of family. To the outside world she could seem as intimidating as a momma bear.

We had to push our way into the café that morning. It was standing room only. Neither of us had ever met Barrett, so my mom, summoning her momma bear persona, called out in a shrill demand, “Where can I find Barrett?!” After the laughter subsided, a reluctant voice called out from behind us, “Uh—that’ll be me.” One of the people we had unceremoniously brushed past at the entrance to the café was our guy.

Barrett was a good-looking man of average height and lean frame. He had an air of cool about him. He even dressed cool, wearing a grey down vest over a faded jean jacket, black denim pants and a pair of tired leather hiking boots. He greeted us with a warmth and affection that was so charming I sensed my mother getting weak in the knees. She responded by turning flirtatious, a side of her I wasn’t even remotely familiar with and, given that I was already self-conscious enough in front of these new peers and this new boss, it made me cringe. I think I still bear psychological scars from that little display.

Barrett handled it graciously and I immediately liked him. Getting him to like me would be no easy task, as it turned out.

Having lived a relatively sheltered existence under my mother’s wing in the big city didn’t exactly help prepare me for what transpired next. Feigning courage as I bid my teary-eyed mother farewell, I found myself surrounded by forty complete strangers; a group that looked more like a band of gypsies than a bush crew. There was no time for introductions. We loaded ourselves into a number of idling bush trucks and made tracks, travelling a half-dozen kilometres back down the highway before turning onto a rough and rutted logging road.

There’s a certain comfort and familiarity in driving on pavement—all of that is lost the second you hit gravel. From that point on we travelled deeper and deeper into the wilderness. I didn’t fully realize it then, but nothing in my life would ever be the same again.

Within minutes our long convoy of vehicles kicked up an unbroken column of thick, choking dust. I couldn’t see the vehicles out in front or the topography on either side of the road. I had nothing, no sense of the surrounding landscape to help divert my attention away from the feeling that I was being abducted, that I was being taken to a place where escape would be impossible. I imagined that this was how young men must’ve felt after being drafted and abruptly hauled off to war.

Finally we arrived. Our caravan pulled into a large landing—an area that had once been used as a staging area or log-sort by a previous logging operation. It was a level, one-acre teardrop-shaped clearing with a gently flowing creek running along the bottom perimeter—a creek that emptied into a series of ponds and marshes several hundred feet below.

Just beyond the landing and across the creek, looming over us like a thunderhead, was a rolling expanse of barren landscape stripped of every conceivable living thing for as far as the eye could see. This was where we were to set up camp. This was where we were to plant our trees. This was where it all began.

Barrett’s camp, as I would later discover, was about as well equipped and elaborate as they came back in those days. It took a good number of vehicles and trailers to haul in the entire setup. A half-dozen trucks and trailers bore the weight of metal frames, lumber, appliances, generators, pumps, sheets of canvas, tarps, tools, fuel and, of course, mountains of food. The most prominent feature of Barrett’s camp: a medium-sized travel trailer that had been gutted and converted into a kitchen-on-wheels. Inside were a large freezer, two commercial-sized refrigerators and a pair of gas-powered stoves. And judging by the assortment of meat, dried beans, grains, fresh fruit and vegetables that were on board, our meals were going to be anything but your standard meat and potatoes fare.

I had my first real look at the crew as the trucks were being unloaded. It was a spirited bunch. It was fairly young too, except for the managerial types who appeared to be in their mid- to late thirties. The men, who outnumbered the women by only a handful, appeared to be in excellent physical condition—lean and mean. A good number of them had long hair, some had ponytails, some wore headbands; nearly all of them sported beards or moustaches. I couldn’t help noticing that several carried acoustic guitars, and perhaps twice as many had bongo drums poking out of their gear.

The women on Barrett’s crew all looked magnificent to me. They seemed extraordinary in every respect: attractive, athletic and high-spirited. They were also generous in making eye contact with the new kid. But beneath the long flowing hair, the provocative assortment of tight-fitting jeans, rock-star tees and tie-dyed tunics, these women all had a certain ruggedness about them. I had no doubt that they could teach me a thing or two about thriving in a remote wilderness setting. I believe I fell in love several times over within the first few minutes of landing at our campsite. Suddenly, the idea of having been abducted by a band of gypsies didn’t seem all that dire after all.

I sensed everyone was sizing me up as well. Apparently, nearly everyone knew who I was. My sister, Lina, who had served as camp cook for this same crew on a recent contract, was admired by all. She was a splendid cook. To this day, I don’t believe I have met her equal. In bush camps few people are held in higher regard than a good cook, and of course she was also the boss’s partner. I suppose this minor degree of celebrity by association gave me a bit of a confidence boost as I attempted to assert myself and find my place.

People knew who I was for one other reason. I was an obsessive guitarist at the time, and a few months earlier I’d sent Lina a thirty-minute cassette tape of my playing. She shared it with several members of the crew, who were apparently impressed. While helping unload gear from the trucks, I overheard a stray comment that I was some sort of a guitar prodigy. I didn’t know it then, but getting together for evening jams was a favourite pastime for this crew and people had rather large expectations for some new sounds, especially when they spotted the acoustic guitar case poking out of my gear. I hoped I could live up to my advance billing.

After helping Denny, our cook, unload his supplies, I lent a hand with some of the bulkier camp components. The dining tent—a semicircular, metal-framed Quonset hut, six metres high by nine metres wide by fifteen metres long—was the main structure. It required a dozen people to assemble. Once erect, it would comfortably accommodate up to sixty people. The front of this massive tent was lined with a series of wooden counters where Denny would lay out lunch items each morning. The back of the tent was open ended, allowing the kitchen trailer to be pulled snugly into place. There it functioned as both a wall and a food distribution centre, operating like a food truck. It had a large window and service counter that opened up inside the Quonset hut. People would line up and fill their plates from an array of food items laid out buffet style. In front of the kitchen trailer, elevated thirty centimetres above the ground, was an expansive wooden platform that served two purposes: it gave some of the smaller people in camp enough of a lift to access the buffet counter, and once dinner was over, it served as a stage for music and entertainment.

Another crew was outside assembling our shower stalls, nailing together two-by-four frames, stretching out tarps and tacking them down tight to create walls. Rolls of thick white hose were extended down to the creek where water was sucked up by a powerful pump and fed into a propane water heater. This supplied hot water to the kitchen, as well as to a half-dozen shower heads.

Lastly there was a group of people busy with shovels excavating a number of deep pits on the periphery of our little village. These pits were to be used as shitters. It was an unenviable task, but one given an appropriate amount of care and attention.

It took about five hours to construct our little village. No detail was overlooked or ignored. It was around that time, after the main camp had been meticulously pieced together, that I began to think about setting up my own campsite. There was a slight chill in the air and the sun was beginning its hastened retreat below the horizon.

I noticed that there were several preferences in site selection. Some people pitched their tents in the heart of the camp, within metres of the Quonset hut. I later discovered that this was for security reasons: we were in bear country after all. Others who were less concerned about bear danger paced off a good one hundred metres or so from the perimeter of our village, preferring to carve out a little piece of real estate near the creek, or up on a hill with a view of the surrounding landscape. The last group put a good distance between themselves and downtown CRC Ltd., up to five hundred metres or more, preferring total isolation when they bedded down at night. I picked the top of a hill that looked down over everything, some two hundred metres away.

As I was pitching my tent, I spotted Barrett on the road below and decided to have another go at establishing some rapport. I hadn’t had a chance at the café earlier in the day. My mother succeeded in monopolizing his attention. Barrett didn’t leap at the chance to make nice. Instead, he rebuffed my comradely approach and rather coldly handed over a brand-new set of multicoloured treeplanting bags and shovel.

“This is it, kid. This is where my responsibility ends,” he said. I suddenly felt very alone in a very big and intimidating new world. I guess it was written all over my face.

“If you’re starting to get butterflies, the highway is in that direction,” he said, waving his arm in the general direction of Highway 16, our only escape route to civilization and home, which was much farther away than anyone could reasonably walk. I was taken aback by that brief, dismissive exchange and walked away with my tail between my legs. Family connections meant shit to Barrett. There would be no special treatment. I had no friend or ally in him.

The next day the breakfast horn sounded at 6:00 a.m. It was still dark. The early morning air was bracing. The sleeping bag I chose for the occasion wasn’t anywhere near compatible with the chill we experienced that first night. Midway through the night I was forced to pile every stitch of clothing I owned on top of myself for additional insulation.

As I stood out in front of my tent, teeth chattering, looking down over the thin wisps of light emanating from the Quonset hut in the distance, I could hear what sounded like reggae music.

Making my way off the hill toward camp, I observed a blanket of icy fog that had settled over the surrounding landscape—it had a palpable density to it. Judging by the ruckus coming from inside the Quonset hut, I was the last person to arrive for breakfast that morning. The music I’d heard earlier was indeed reggae, and it was coming from inside the kitchen.

The atmosphere inside the Quonset hut was frenzied, filled with tension and nervous energy as people vied for position at the lunch and breakfast counters. The beautiful women I had observed only twelve hours earlier were barely recognizable in their ponytails, thick sweaters and down jackets. The bags under people’s eyes spoke volumes. This was a time of transition. Swapping out the warmth and comfort of one’s four-poster in the city for a thin foamy and sleeping bag was not an easy trade.

I was not a morning person. I preferred to begin my day in an environment completely free of chaos and stress. I wrestled with the idea that this discordant early morning routine would greet each and every one of my days for the next three months. Home had never felt so far away.

By 6:50 a.m. the mosh pit in the Quonset hut was reduced to a dull roar. By 7:00 a.m. the crew had assembled outside for a meeting with Barrett and his foreman. People were outfitted with backpacks, rain gear, work boots, water bottles, shovels and treeplanting bags.2 After the meeting, people broke into three smaller crews and walked off in the direction of the large clearcut that loomed ominously over our tiny village. I, along with five other stragglers, watched as the procession of planters crossed a small bridge over the creek before disappearing into the fog-shrouded landscape. Those of us who remained formed the “rookie” crew. And we were about to be served a very large dose of reality.

The rookie crew was equally split between genders—three guys, three gals. The women were the obvious standouts. They were all university students, athletic, high energy, attractive. I had an immediate connection with a tall, lean redhead named Debbie. She was a vision of loveliness. Her eyes were what drew me in: large, expressive, hazel. Her face was dotted with deep brown freckles, which I immediately found myself fixating on. Her copper hair, which tumbled along her shoulders when she walked, rounded out the vision. She also possessed a sharp wit, but you had to listen for it as she liked to speak in soft tones, especially when sarcasm was her objective. We were instant friends even though she was three years my senior. I was in love.

After a one-hour blackboard-assisted lecture on general safety and treeplanting basics, we were told what was expected of us: plant a minimum of one thousand high-quality seedlings per day by day fifteen, or go home. One thousand trees per day—judging by the stunned looks on peoples faces, I suspected there were those who doubted their ability to even count that high.

If achieving this seemingly unrealistic production goal wasn’t enough pressure, we were informed that we would be strictly supervised, that every one of our planted trees would be examined “under a microscope.” This was to ensure that the roots were planted properly, that they were in a specific soil, at a specific depth and that the rest of the tree was perpendicular to the ground. We were also expected to plant our seedlings at a specific distance apart from one another, ideally on a 3.2-metre grid pattern across our entire area. This criterion seemed doable if we were planting trees on a golf course putting green, with no obstacles to manoeuvre around. Of course there were no putting greens to be had within hundreds of kilometres of our camp, nor was there anything even remotely resembling one.

The terrain we were dealt on our first day consisted of a series of rolling hills rising high above the road on which were assembled. We stood, gazing up at the clearcut landscape with slack jaws. At the crest of each hill were layers of exposed bedrock forming sharp stratified ridges, some of which appeared to be completely devoid of soil, their bleached and weathered edges resembling whitecaps on a choppy sea. There were large boulders randomly distributed across the entire setting. Stumps and discarded “junk trees” littered the landscape like lifeless limbs and torsos on a medieval battlefield—the aftermath of the harvesting process. There were large concentrations of slash everywhere, and apparently these areas needed to be probed thoroughly for any hint of soil.3 There was also water, both stagnant and flowing. Large volumes of it coursed through the numerous gullies and ravines that were chiselled into the landscape, fed by a source much higher in elevation, gravity mobilizing it downward. Much of the coursing water, after being channelled under our feet through a series of culverts buried beneath the road on which we stood, continued its rapid descent, disappearing into terrain below. Some of the water eventually collected in pools along flat benches near the bottom of the clearcut. We would soon discover that the fringes of these pools were swamp-like, with soft muck, even quicksand, lining their outer edges. And it was on this terrain that we were expected to plant our seedlings on a 3.2-metre grid to exacting standards. I swallowed hard several times and considered the futility of such a task.

Our taskmaster was an extremely arrogant and peevish character named Jeremy. He insisted on giving us his entire resumé—every annoying detail of it. He was a mountain climbing expert, a survival expert, a search-and-rescue expert, a martial arts expert, a treeplanting expert and, judging by his behaviour around Debbie, a smooth-operating female-treeplanter expert. I hated him.

Jeremy was a good instructor, though. He wasted no time arranging us in a line and setting us in motion. He demonstrated in minute detail the mechanics of putting one’s shovel blade in the ground, opening a hole, sliding a seedling’s roots in, closing the hole and pacing off the proper distance to the next spot. It wasn’t easy. There were areas where the soil was simply too shallow, where the level of slash was too deep, where large obstacles and water courses impeded forward progress—where planting trees on a 3.2-metre grid was a physical impossibility.

Rattled by the lofty expectations thrust upon us, we worked nonstop that first day. I struggled to maintain my balance on the broken, uneven terrain. I attempted to use my athletic prowress to produce a fluid motion, but I couldn’t develop a rhythm. It was like learning to walk for the very first time. My final tally at the end of day one: ninety-five trees! And I was by far the highest producer on our rookie crew.

We ended our first day as treeplanters feeling completely overwhelmed. One thousand trees by day fifteen, or else! They had to be out of their fucking minds. No one could conceive of attaining such an absurd goal in such a short period of time. This dominated our conversation on our hike back to camp. That is, until we approached the bridge near the edge of camp where our loud, boisterous discussion trailed off into stunned silence. Crossing the bridge, we were greeted by a half-dozen women from the regular crew who were bathing in the creek below. They were completely naked. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I remember questioning my senses, wondering if what I was witnessing was real. It was real. And it was by far the most captivating display of the female form I had ever encountered in my nineteen years. Six voluptuous lily-white bodies, all in proximity and without even a hint of self-consciousness, using the cool clear creek water to wash away dirt and sweat from their exhausted, ethereal frames. They paused briefly, just long enough to toss us a friendly wave as we filed past— muffled giggles could be detected once we were clear. The images I took in during those precious few moments had a profound impact. They were indelibly imprinted in the pleasure centres of my brain. If I had felt even the slightest hesitation or doubt in my commitment to tough it out prior to this glorious and sublime event, those feelings were immediately cast aside.

Debbie and I ate dinner together that evening. We tried our best to console one another after a gruelling day on the slopes, a day that seemed to produce more questions than answers.4 We both responded politely, albeit reluctantly, to the inevitable queries from some of the more experienced planters on the crew. Questions like: “Tough day on the slopes?” and “Did you pound in a grand today?” and the most annoying one of all, “How goes the war?” After enduring the same line of questions from over a dozen people, I broke away from Deb and sidled up to a small group of veterans who had assembled around the wood stove. The sun was low on the horizon and the temperature was dropping by the minute. Over the crackling of a cedar fire, peering through clouds of cannabis and tobacco smoke, I listened in on their conversations, hoping to glean any insight that might offer an edge. It wasn’t long before they shifted their focus toward me and I became the centre of attention. The advice and counsel came rapid-fire and from every direction. Even those who weren’t part of the conversation, who overheard bits and pieces as they were passing by, chimed in with nuggets of wisdom, all for my benefit.

The general consensus among this group of highly skilled individuals: don’t stop moving—never pause—learn to conserve movement—eliminate any unnecessary motions—always scan the area ahead—learn to take mental snapshots of the ground immediately in front of you—plot your next three or four moves in your mind—never stop moving. Incredibly, this made sense to me, and with all of this fresh intel swimming around in my head, and after bidding Debbie a warm good night, I strolled off into the cold night air, in the general direction of my tent (I remembered to pack a flashlight with me from that evening on).

There’s a strange phenomenon that plagues nearly every rookie treeplanter at night during their first few shifts. Their dreams are monopolized by planting scenarios, and in particular, grid patterns. Whether the setting of your dream is a shopping mall, your mom’s kitchen or the surface of the moon, there’s a powerful compulsion to establish a 3.2-metre grid pattern. Everywhere! I cannot tell you the number of times I woke up in a cold sweat, frustrated because I was unsuccessful in pacing off an acceptable grid pattern over my dreamscape.

The second night in my tent followed a similar pattern to the first. It became bitterly cold in the wee hours of the morning. Not only was I forced to pile every stitch of clothing I owned on top of my sleeping bag for additional insulation, I actually wore several pairs of underwear on my head in order to trap body heat. I remember waking up, wondering if I’d ever be able to restore my dignity.

I was determined to approach day two on the slopes with a new strategy and mindset. I was determined to stay in motion no matter what the circumstance. This is easier said than done, especially when one’s terrain is riddled with obstacles that hinder forward progress and limit one’s view of what’s ahead. But the strategy began to pay off. By midday, I astounded Jeremy with a total of 120 trees. By day’s end I managed to pound in 275 trees. Having shared some of my recently attained insights with Debbie, she too was able to plant over two hundred seedlings that day. The rest of our rookie crew were struggling to crack the one hundred level, and on the hike back to camp at day’s end, I revealed my secret. Sadly the bathing beauties we’d encountered near the entrance to camp on the previous day were not in evidence. Apparently they had discovered the showers.

The strut in my step, having bettered my previous day’s score by 200 per cent, was lost soon after returning to camp. The average number of trees planted across all three (experienced) crews that day was thirteen hundred trees, with some of the faster planters pounding in an astonishing sixteen hundred (I was told that those numbers were expected to rise as the people began hitting their stride). Still, my score was a vast improvement over the previous day, and for the first time since arriving in camp, Barrett acknowledged my presence with a mock tip of the hat.

After dinner that night, Debbie and I took a seat next to the wood stove. There, I found myself studying the behaviours of the crew as they mixed and mingled, paying special attention to the women I’d admired at the edge of the creek one day earlier. It appeared to be a very vibrant, animated and sexually charged atmosphere. It reminded me of some of the parties I attended back in high school. There seemed to be an inordinate amount of flirting and petting going on, and I couldn’t decide if it was merely an extremely friendly group of people or the prologue to an orgy. Debbie sensed the heightened state of arousal too, and found it as intriguing as I.

Understanding that Deb had a few years on me, I decided to probe her for details regarding her private life anyway. She explained that she had a boyfriend back in Vancouver and that it was fairly serious. She also said that he planned to drive up to meet her in Prince George during the break between contracts. I wasn’t surprised. I couldn’t imagine such an incredible woman being single.

By day three, with the moral support and wise counsel of several veteran highballers, I was halfway to my target of one thousand trees per day. By the end of day four I managed to plant four full runs of two hundred trees per run—a grand total of eight hundred trees.5 It was at that point that I came to the realization that planting large numbers of trees was as much a mental process, if not more so, as it was a physical one. There appeared to be a mysterious underlying dynamic at play, one that could be tapped and exploited with the right amount of focus, forward motion and conservation of movement. I also came to realize that things could become very interesting from a monetary perspective. The crew’s average at that point was fourteen hundred trees per day. If I succeeded in achieving that level, at 11¢ per tree, I would gross $154 (the equivalent of $350 in 2019 terms). Righteous bucks!

Day five was a day of rest. Barrett had established a schedule of “four and ones”—four days on, one day off. I used the opportunity to sleep in until 6:30 a.m., do my laundry in the creek and take my first shower in nearly a week. Stripped naked, it appeared as if I were wearing a dark brown belt and suspenders—it was the exact outline of the mud-caked support straps on my treeplanting bags. It wouldn’t wash off. The dirt and grime appeared to permeate my skin cells right down to the DNA. I then understood why some of the more fastidious planters on the crew showered daily and had long-handled brushes sticking out of their shower bags.

There was something very odd about the shower setup itself: there were no dividers, no stalls—only a single large enclosure with six shower heads spaced a metre apart. Oh, how the mind wanders when you’re all of nineteen years of age, in a remote wilderness setting, surrounded by women who appeared to be more comfortable with their clothes off than on. But I was determined to stay focused. At the beginning of the contract, Barrett seemed convinced that I was some kind of a flake. He even had the temerity to show me in the direction of the highway. Despite the adversity, the punishing pace on the slopes, the dirt, the extremely cold nights and the humiliation of waking up with underwear on my head, I was determined to carve out a niche on this crew.

1. “Highballers” are the highest-producing treeplanters on a crew and are generally held in the highest regard.

2. Treeplanting bags are used to carry seedlings. They consist of a series of large pouches crafted out of heavy canvas or nylon. The pouches are attached and arranged along a thick belt with connecting shoulder straps. Two pouches ride along each hip, and a third pouch rides along one’s butt. The three pouches, if fully loaded, can carry many hundreds of seedlings at a time.

3. “Slash” refers to piles, large and small, of wood debris and waste.

4. The terms “slopes,” “clearcut,” “cutblock,” “block,” “ground,” “planting area,” “area,” “piece,” “unit” and “land” are synonymous. They all refer to an area that has been harvested or cleared of trees—an area slated to be planted with seedlings in order to grow a new forest.

5. A “run” refers to the task of filling up one’s treeplanting bags with a specific number of seedlings and planting said seedlings until one’s treeplanting bags are empty.