Читать книгу Mah Jongg: The Art of the Game - Gregg Swain - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| CHAPTER 2 Mr Babcock Invents Mah-Jongg™ |

A chance meeting on a train in Oregon in 1917 led to the Mah Jongg craze of the 1920s. Joe and Norma Babcock met Anton and Helen Lethin and discovered that they shared a great deal in common. Both couples were newlyweds and both were booked on the Siberia Maru bound for Shanghai, China. Joseph Park Babcock had been a representative of the Standard Oil Company in Soochow for the previous five years. Anton Lethin had a position with the International Correspondence School in Shanghai. The couples formed a lasting friendship on their journey.

One windless day on the Yangtze, aboard a listless houseboat, Babcock observed boat crewmen playing a game with intricately carved tiles. Fluent in the local dialect, he learned the game in detail. The more he played the game, the more he became convinced of its sales potential back in the United States.

Left The arbiters of Mah Jongg’s rules are here, with Joseph Babcock squarely in the middle.

On one of their trips to Shanghai, the Babcocks introduced “Mah Jongg” to the Lethins, who struggled with it at first. The game’s rules were complex and not written down, and the tile designs were in Chinese. Babcock wrote simplified rules and added Western indices to the tiles. Lethin now saw the game’s potential, but neither man could finance a business so Lethin approached his boss, Albert R. Hager. When the game received rave reviews from the expatriate community in Shanghai, the Mah-Jongg Company of China was formed. Patent and trademark applications were filed in the United States.

Babcock contracted W. A. Hammond’s lumber company to ship sets to San Francisco, where the game’s sales were good but not great. Setting his sights higher, Babcock recruited a Mr Dyas to pitch Mah Jongg to Parker Brothers. George Parker tried a test run through several New York department stores but sales were disappointing, so Parker declined. Hammond, meanwhile, used marketing promotions in West Coast department stores. Players got free lessons and bought sets, Chinese clothing and decorations. The campaign sparked excitement. Everyone wanted this new game. Newspapers picked up the story, sales skyrocketed, and George Parker took notice. He bought the trademark and copyright from Babcock’s company. Unfortunately, the Mah Jongg wars would soon come to a head.

Above This photograph was taken by Edward Steichen (1879–1973) for Vogue, c. 1925. The caption read in part: “Close-up of the hands of model and writer Ilka Chase as she plays with mah-jongg tiles: rope of pearls wrapped around one wrist; on the other arm an emerald and diamond bracelet (the emerald conceals a timepiece), and a diamond bracelet; an emerald-cut diamond ring; all from Cartier.”

Babcock’s Mah-Jongg Sales Company of America had signature designs, including the Green Phoenix and Red Dragon and One Dots with “Free Mah-Jongg” in the center. This version has continuous Flower tiles with Chinese scenes.

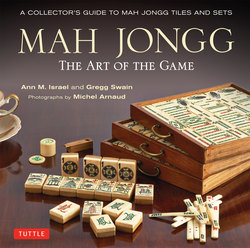

Babcock’s “Style No. 8,” set in a rosewood box, which retailed for $100. The top features eight-petaled rosettes, brass handles, and butterflies, and its sides depict Chinese coins. An ivory button opens the door of the box. No detail was overlooked in the design and manufacture of a set meant to have a place of honor in the home.

Right In addition to a Mah Jongg box, a radio set was a must-have in any well-appointed parlor. These women are learning how to play the game by listening to the instructions on the new electronic marvel.

Advanced players objected when novices made cheap quick wins, thwarting high-scoring wins, so various rules were devised to prevent cheap wins. Many competing books and rules confused and discouraged new players. Auction Bridge and Mah-Jongg Magazine, Vanity Fair, and the Herald-Tribune published polls to determine the most favored rules. The publisher of Auction Bridge, John H. Smith, formed the Standardization Committee of the American Official Laws of Mah-Jongg, consisting of Mah Jongg authors Robert Foster, Lee Hartman, Milton Work, Joseph Babcock, and Smith. The poll revealed three rule sets at the top: Mixed Hand (the Chinese rules), Cleared Hand (a hand must include tiles of no more than one suit), and One Double (minimum high score required). The three were incorporated into the Official Laws, but it was too late. The enthusiasm for Mah Jongg was fading.

After the initial craze ended, Mah Jongg evolved into many different national and regional variants. Were it not for Babcock, this enduring game might never have spread so far and wide.

This “Tuxedo” set has wooden tiles covered by a thin wafer of French Ivory laminate. If the name of that swanky enclave in Upstate New York could not give the game cachet, then certainly the brass plaque, placed by Parker Brothers, would.

Overleaf Many companies tried to compete with Babcock. These are some of their books of rules. A British version of Babcock’s ubiquitous Red Book of Rules is at lower right, along with clippings of his syndicated column “Mah-Jongg” from the Wichita Beacon in 1924.

Detail of the lid of a box of game cards made by Deshler Imports of Shanghai.