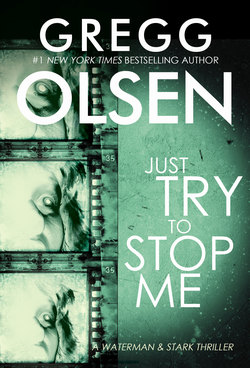

Читать книгу Just Try to Stop Me - Gregg Olsen - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOURTEEN

Birdy watched from the sofa where she was reading the front page of the Port Orchard Independent. It was the usual—someone complaining that not enough was being done to repair a downtown restaurant that had burned and remained an eyesore, a listing of some potential names for the mayor’s spot, and a human-interest story about a llama rancher from Olalla. Elan was down the hall in front of the mirror fiddling with his hair.

“She must be special,” she called out, looking up from the paper.

The teenager cocked his head and grinned.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

Birdy smiled back. “Elan, you’ve been spending more and more time getting ready to go out the door.”

He stepped out into the hallway, all white teeth and dark wavy hair. Elan wore a light blue T-shirt with some kind of a graphic design, though it was too abstract for Birdy if she’d been asked to describe it later. Which she hoped she never would. Around his neck was a silver chain that he always wore, but it sparkled more and Birdy wondered if he’d actually polished it. He had on dark dyed jeans. On his feet were black boots that made him look even taller than his 5-10 frame. With his mane of dark hair and his dark eyes, he was undeniably a good-looking kid.

Although, when she thought of it, Birdy could see that the boy had ebbed into a young man in the months since he came to live with her. They were a family, though their connection was fragile at first. The awkwardness of their relationship had dissipated following the disclosure that she was his sister, not his aunt as he’d always believed.

She’d always be Aunt Birdy, however, which made her very, very happy.

“Yes, so yeah, I’m kind of seeing someone,” he said. “It isn’t a big deal. You’ve met her already.”

Birdy folded the thin, little newspaper and set it on the coffee table as Elan stuffed his hands deep into his pockets and slumped into the chair across from her.

“I have?” she asked, a little surprised. “News to me. Where? When?”

Elan scraped his fingers through his hair again.

He must really like her, she thought.

“That time when you dropped off my lunch, which by the way still ranks as one of the most embarrassing moments ever visited upon a nephew/brother. Like ever.”

Every now and then Elan would tease her like that. He’d called her Aunt/Sister Birdy a time or two, though mostly Aunt Birdy, thankfully so, the preferred name he offered when speaking to others about her. She didn’t mind. It had been a lot for Birdy, her sister, and Elan to deal with. The woman at the center of the long deception, Birdy’s mother, Natalie, had remained inflexible about rectifying that discrepancy on the family tree.

He was her grandson and that was that.

“I thought we agreed to get over that lunch thing,” she said, smiling.

Elan fiddled with his phone. “Yeah. Sorry. But really, it isn’t just me. Most kids would rather starve than have their mom or aunt or sister come to school with a Tupperware lunch container.”

The Tupperware was a total mistake. No doubt about that. Nothing said dork like Tupperware.

“You’re avoiding the question,” she said. “Who’s the girl?”

“Amber Turner,” he said, looking right into Birdy’s eyes for a flash of recognition.

“I’m sorry? Who?”

Elan sighed. “Aunt Birdy, Amber’s the girl that’s one level above me, popularity-wise, but we’ve really been having a good time hanging out. She’s the one that you thought had the cool hair.”

A flash of recognition came to her.

“The one with the long, red hair?”

He smiled. “Yes, that one!”

“She seemed nice. Pretty too.”

Elan made a disgusted face. It was exaggerated and meant to poke at something Birdy had told him one time when they walked down to the café at Whiskey Gulch and talked about life, girls, life and girls.

“As my aunt told me, pretty doesn’t matter,” he said. “Smart does. She’s smart too.”

Just then Birdy knew she could not love that boy any more if he’d been her own son. He teased her. He listened to her. That meant everything to Birdy.

“She’s picking me up tonight,” he said. “Going to hang out at the bowling alley. She’s not only smart and pretty, Amber has a car, too.”

“That makes her a total catch,” Birdy said.

Elan grinned. “That’s just what I thought.”

“Bring her in to say hello,” Birdy said.

Elan shoved his phone into his pocket. “We’re not serious, Aunt Birdy. We’re just hanging out.”

“Sure, but you took more time on your hair just now than I do before speaking at a forensics convention.”

Twenty minutes later, Birdy was in the kitchen fiddling with the ancient electric oven that had long threatened to give up the ghost and finally had. She surveyed the element to see if she could make do with it for another week. It had been hit or miss on its thermostat settings so much so that she’d relegated all of her cooking to the microwave. And that work-around had brought more than one disaster at mealtime. The broccoli casserole was a complete failure, though Elan insisted that no matter how she cooked it—microwave or conventional oven—it would have been an epic fail.

“No one likes broccoli,” he told her. “At least no one I know does.”

“I do,” she’d answered back. “Do I count?”

“Yeah, I guess.”

She heard Amber’s car pull up, and Elan called out good-bye.

“Don’t be late,” Birdy said. “If you are you’ll have to eat broccoli casserole every night for a week.”

“That’s cruel and unusual punishment, and you know it,” Elan said as the front door slammed shut.

Birdy considered bowling cruel and unusual punishment, but it was better than hanging around the mall or even worse, on some remote Kitsap beach doing what teenagers do.

Alone and thinking of bowling, the forensic pathologist’s thoughts rolled back to a decades-old murder that occurred at the Hi-Joy Bowling Alley at the base of Mile Hill in Port Orchard. It was one of the cold cases she’d added to a file box she called the Bone Box—cases that others had deemed unsolvable. She didn’t feel that way. She was certain that a cold case was only a cold case until someone turned up the heat. She kept the Bone Box in her home office.

The victim in the Hi-Joy murder case was a thirty-one-year-old janitor named Jimmy Smith. It was a brutal crime—occurring long ago. Before Birdy was even born. Yet it resonated with her when she first took her job with Kitsap County. It had been the kind of messy case that brings the victim into the autopsy suite piece by piece. Literally. Jimmy had been killed with a hatchet.

Birdy studied those old crime-scene photos, the imagery of the brutality rendered in gorgeous black and white. She saw the force with which the assailant had struck the victim. She could see he’d been right-handed. That he was taller than the victim. That whoever had killed Jimmy had done so in a rage.

At first authorities suspected a robbery gone wrong—but the till was full and Jimmy’s wallet hadn’t been taken from his jeans pocket. It had long been suspected that the crime scene had been tampered with and that the man behind the murder was the chief of police. The evidence left at the scene was circumstantial at best—a shoe print matched the size of the chief’s. Later his wife told investigators that he’d come home with bloody clothes.

It was the way things were handled at the time. The facts about the chief that had emerged over time were troubling. He’d been the only one to secure the evidence, elements of which swiftly went missing. And later, adding credence to the rumors of his potential involvement, he was convicted some years later of sexual assault and sent to prison.

Birdy wondered about two things as she gave up on the dying and possibly dangerous oven. She wondered why it was that her personal frame of reference for every little thing seemed to tie into murder? It was a bowling alley, a place of smelly shoes, rock and roll, and over-foamed beers. That’s what most people thought. Not her. A park on a sunny day? That’s where a girl had been raped. A shopping center she passed by occasionally in Tacoma? That’s where a little boy went missing before a K-9 team found his body in a culvert two miles from the scene.

She couldn’t answer exactly why it was that she often thought in those terms. Occupational hazard maybe? Sometimes she tossed it all off as something vague, that the tendency to imprint on things in a dark way was just how she was wired. Somehow she always could see the undertones of the grim under the sparkling veneer of pretty.

And the other question that weighed on her mind just then? Exactly what time did the appliance store open the next morning?