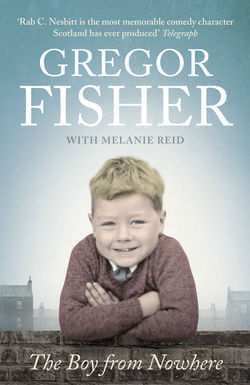

Читать книгу The Boy from Nowhere - Gregor Fisher, Melanie Reid - Страница 8

CHAPTER 1 The Curly-Haired Boy in the Corner

Оглавление‘I have always depended on the kindness of strangers’

Blanche DuBois in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire

Thump.

Pause.

Thump.

Pause.

Thump.

Three thumps – never more, never less. No cheery ‘Hallooo!,’ no cry of ‘That’s me, Cis,’ just three dictatorial thuds on the bedroom floor with his foot. John Leckie wanted his breakfast. After a lifetime working the night shift, this was the signal to his wife in the kitchen below to say that he had woken up. It was 5pm, and Cis would prepare tea, toast and marmalade and take it upstairs. Mr Leckie ate upstairs and then came down: a tall, stern, well-built man, ready to go to work. The child, sitting silently, for it was best to keep quiet, would look up and see the great long legs of his boiler suit appearing down the stairs.

John Leckie was, it’s fair to say, as much a creature of routine as he was a man of few words. There was no conversation. He put a long, dark trench coat over his overalls, clapped his grease-stained engineer’s bonnet on his head and picked up the lunchbox Cis had prepared earlier. His lunch, his ‘piece’, was a thing of precise wonderment. It stayed exactly the same for nigh on 50 years: an ancient little Oxo tin containing sugar and loose tea, mixed before it went in, and cheese sandwiches in waxed bread paper, made with the well-fired top of the loaf. John Leckie was as set in his ways as he was undemonstrative. Leckie would nod to his wife and leave for the night shift in the great engineering works in the city. Nor were things much different when he returned home in the morning, weary and grimy. He came in, said little or nothing, took off his overalls, ate the meal Cis had prepared for him and climbed the stairs to bed. Soon it would be time to bang on the floor again for breakfast. Such was the unflinching, unchanging traffic of his life.

At weekends, John Leckie, in an old shirt and trousers and tank top with holes in it, would sit, not in an armchair but on a wooden slat-backed kitchen chair by the fire, his legs spread wide on the hearth, both hugging and hogging the heat. It was always cold in the 1950s. He would spend hours sitting there, hour after hour, in his own silent, still world, staring at the fire. No radio. No books. No conversation. He ignored anyone else who might be in the room. On the mantelpiece were his smoking paraphernalia, neatly arranged – a box of Capstan untipped full strength and the occasional half-smoked cigarette, extinguished early and saved. He would take the tobacco out and re-roll it. There were no matches – he made tapers from tightly rolled sheets of newspaper. When he stood up to smoke, which was frequently, he lit the taper from the fire and put it to the cigarette. The taper was carefully stubbed out and propped at one side of the fire to be re-used. He’d smoke his cigarette standing over the fire, and then sit down again. Occasionally he coughed. And if he needed to fart, he simply lifted one cheek of his backside and farted. No apologies. No glance around. ‘This is my house,’ announced the fart. ‘I’m the main man here.’ It was a thing of wonder to the little boy who observed. And Mr Leckie would continue to sit there, legs astride the fire, coal bucket sitting beside him. Eventually the fire would start to burn lower.

‘Cis,’ he would call in the direction of the kitchen.

Not a question, an order.

‘Uh-huh?’

‘Coal.’

And she would leave off what she was doing and come through to load coal upon his fire to keep him warm, while he sat there, unmoving. If he did speak, when she had done as he asked, it would only be to criticise the quality of the fuel she had put upon the fire.

‘There’s too much dross in that.’

The small boy remembered the day he arrived at John and Cis Leckie’s house, at the tail end of 1957. It all seemed so simple, back then. He was only three years old and Cis was his mother. Of this he had no doubt. He remembered the day he arrived there because it was snowy and they drove him up to where she lived, at the very top of the hill. He needed a pee and they had to stop the car on the slope. He remembered the pattern his pee made in the snow. He was a sturdy, smiley little chap with heart-melting blond curls and bright blue eyes. That first night, when her husband was at work, Cis carried the child outside to the loo because in 1950s Scotland most people still had outside toilets. The house sat high up to the south above Glasgow and it was a cold, frosty night – he could see the city lights twinkling and he thought he’d died and gone to heaven.

Safe, really safe, in Cis’s arms, looking at the lights.

He’s outside, pacing the decking, smoking a Gauloise. It’s Stirlingshire, Scotland, May 2014, and he’s on a flying visit from his home in France. Restless, wary, but eager, he really wants to talk. This has been a long time in the brewing, more than 60 years.

‘It’s really quite complicated, my story,’ says Gregor Fisher, actor, comic legend, man o’pairts. He pauses. ‘I just remember thinking that it was like trying to sort out a pile of spaghetti, or finding the ends of a tangled ball of wool. I didn’t know how to get to the bottom of this, or if I ever would, actually.’

It was a great place to grow up, that house at the edge of the village of Neilston in Renfrewshire, where there was countryside, animals, freedom, friends, mischief – affection and laughter. The family had an acre of land, once a market garden, up there on the hill, and the new child was the prince of all he surveyed. Some would say kindly that it was an eccentric house, others, more judgemental, that it was like Steptoe’s yard. Hens pecked around the back door, the odd goose waddled across the yard, a friendly old dog mooched. Primitive but of its era, the kitchen housed a deep Belfast sink that had a big, wooden step on the floor in front of it, so that Cis, who was not much more than five feet tall, could reach into the water. There was also a very old black range, with a built-in oven and hob. Later, in a nod to the 1960s, it would be taken out and replaced by a Baby Belling: a two-ringed cooker. In the living room was John Leckie’s open fire, with chipped tiles around it and a back boiler to heat the water. The fire was his territory; Cis stoked it, but he controlled it. It heated the house and provided any hot water there was. You got scrubbed in the big sink in the kitchen but you had to book a bath and they didn’t happen very often.

And if a bath was deserved, Cis used the poker to flick the lever at the back of the fire so the heat would be diverted to the boiler. At night she would load the fire with dross, or slack – the powder left at the bottom of the coal bunker – to keep it going, and it was her job to revive it first thing in the morning before anyone else was up. There was no other heating, but nobody ever thought there was anything odd about that, it was just the way it was. You came down in the morning, you got dressed in front of the fire. Sometimes Cis would stand, back to the flames, and lift up her skirt behind her to get a heat. A fleeting luxury.

‘Ah, that’s nice!’

Back then Scotland was a thoroughly tough country. It’s hard for us, from the comfort of the twenty-first century, to grasp just how tough it was. The gap between rich and poor was vast. As the Historiographer Royal, T. C. Smout, put it, simply and bluntly, the expectations of the working class were a hard life, a poor house and few material rewards. And, we can add, an early death. Basically, this meant 85 per cent of the population. By the 1950s, things were starting to improve, but everything was relative. John Leckie’s family, it must be said, were much better placed and more prosperous than many. They owned their sturdy, detached stone-built house; they could grow food and keep poultry to supplement their diet. Nevertheless, life, for them all, was a serious business. In working Scotland, pre-antibiotics, pre-welfare reform, you didn’t ask for anything. You sought to survive.

Gregor Fisher, the little boy with the winning blue eyes, landed lucky. Here, his was to be a stable childhood, in a society marked by thrift, hard work, regular church-going and what today’s children would regard as sensory deprivation, if not neglect: no television, few toys or holidays, even fewer luxuries, old-fashioned rules of discipline. Waste was unheard of, everything old. Wooden furniture. A 1930s brown sofa with a lever that, when pulled, lowered one end, turning it into a daybed. His new mother’s wooden carpet sweeper, circa 1925, with metal wheels, did its best on the old rugs laid on top of the linoleum floor. ‘Wax cloth’, his mother called the lino. There was a single light bulb hanging from a wire in the middle of the living-room ceiling; if you left it on when you went out of the room there was hell to pay. Always there was a dog that his mother was looking after for some old lady or other who was unwell; or somebody had died and left a dog and Cis, out of the goodness of her huge heart, would take the creature on.

She had a soft spot for animals and she loved her hens. There were lashings of fresh eggs; Gregor remembers yolks like Belisha beacons. At certain wintry times of the year the hens were invited in the latch door at the side of the house and took up residence in the kitchen. A hen that was sitting on eggs, or a nest of chicks, would be kept either side of the range in a cage, and when the chickens got bigger and it was still cold outside, they would perch on the top of the kitchen door. Cis would put sheets of newspaper underneath the door to catch their droppings, but woe betide anyone who forgot and came down in the morning with bare feet.

When Gregor arrived, John Kerr Leckie was 56, and Cis about 50. They had a grown-up family – Margaret, 29, who was a schoolteacher, and Una, 23, who was a school secretary. At that time, the daughters were unmarried and still living at home, but out working every day. The little boy slept at first in bed with his mother when John Leckie was away at work; he remembers the bliss of sleeping in the big, warm bed, safe in her arms, and then, in the morning, when she got up, he used to roll into the cosy nest where her body had been. That was the best moment of all. There in the cocoon he knew for sure that everything was right in the world. Before long, though, before he was old enough for school, his new sisters decreed he should have a room of his own. There was a deep walk-in cupboard upstairs, under the coomb of the roof, with an internal window into their bedroom. It was wide enough to fit a single bed in, so the girls papered it with cowboy wallpaper and after a couple of nights of protest – ‘I want to sleep with Mummy!’ – he realised having his own room was actually quite nice.

There was no heating in the bedrooms; horsehair mattresses on the beds too. No insulation in the roof or the walls. When it got really cold, coats were piled on top of layers of blankets. Gregor had so many blankets he was riveted to the bed with the weight, and piled on top of them was a moth-eaten fur coat of his mother’s to keep him even cosier.

We forget how events of the twentieth century shaped lives, altered personalities. Conditioned by decades of consumerism and relative affluence, we are fast losing the ability to grasp how little ordinary people in those days possessed. Cis and her husband had lived through the Great War, the Depression and the Second World War. Prudence and austerity had defined their lives, were set in their bones.

In an era when people aged fast, where no glossy magazines existed to proclaim that 50 was the new 30, Cis and John Leckie looked and dressed like Gregor’s grandparents. It meant nothing to him. In the early days he did not understand that Cis was physically too old to be his birth mother. Why should he? He was too busy surviving on instinct, this child who was as pretty as pie. Butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth, he was quite simply the curly-haired boy in the corner; his life revolved around him. He knew his name was Gregor Fisher and Cis Fisher was his mother, except she was married to John Leckie, so she was called Cis Leckie. She was still his mother, nevertheless. He called her Mum, that’s just how it was. There were some unexplained things when he was growing up, but he didn’t ask any questions, he just accepted that was the way it was. As far as life was concerned, he and his mother were. He knew she was different from his pals’ mothers, but he didn’t care. What mattered was that she adored him. He had what he craved; he was content. Looking back, he realises just how lucky he was to find her – ‘Like so many things in my life, it was meant to be.’

They brought out the joy in each other. He and Cis would constantly set one another off laughing. They laughed when she put him to bed at night, giggling about all kinds of nonsense; they would sing songs and do silly things together. She gave him unconditional love and attention. Maybe she just had a bottomless love for waifs and strays. Whatever the reason, her love saved Gregor Fisher, forged him and still sustains him. He openly acknowledges that he couldn’t live without what he got from her, nor would he have achieved what he has. And today, when he talks about her, it is the closest he comes to tears.

Cis can be described as an ordinary, extraordinary woman, or perhaps an extraordinary, ordinary woman. She was just one of hundreds and thousands of wee West of Scotland ladies who were the cement and the oil and the glue and the lifeblood of their families. Every day she wore a wrap-around pinny and coiled her long hair in a bun under a hairnet. Her red hair was going grey. She had a jam jar with red hair dye in it, and Gregor remembers watching her dip her comb in it and spread it into her hair, then shape it into a bun. Her diminutive size belied her determination and strength of personality.

Cis was a full-time housewife. The only time she sat down, Gregor remembers, was with him on her knee to listen to Listen with Mother on the wireless or when she read The People’s Friend. She carried the coal and went for the food, cooked, washed, cleaned, fetched her husband’s cigarettes. She got up early and set the fire before any of her family came downstairs. No one ever went hungry in Cis’s house, and food is a great way of doling out love. She had a routine of big family suppers late at night: scones, cheese on toast and cups of tea. The family could tell the day of the week by the main meal: one day they had stew, then there was mince, on a Friday there was fish. Every Friday afternoon Cis and Gregor, in the days before he went to school, would catch the bus to Shawlands in Glasgow to get Scotch mutton pies from Short’s in Skirving Street for Saturday and fresh butter in a pat from Henry Healy’s, the City grocer.

Cis’s sister, Aunt Agnes, conveniently lived in Shawlands too, in what the little boy considered rather an exotic, tenement flat. Best of all, she had a piano, which Gregor was mad for, and for him it was the highlight of a Friday afternoon, going thump, thump, thump on the keys, because somehow music was in his blood but he didn’t know it then.

So there was never any choice about what was for supper, nor were those the days of sweet potato with cumin and rocket and a poached egg on top. Plain food, plain lives, few expectations … there was no experimentation whatsoever. It was mince, stew, big pots of really good soup and baking. Gregor enjoyed his food. His mother made rhubarb tarts and apple tarts, she did a top-class fry-up and she also made the best shortbread he could ever hope to taste. Plainly, she and her sisters were a family of bakers, for Aunt Agnes had been at one time industrious enough to start up her own bakery shop.

But this was an extremely male-dominated society. Women like Cis, fathered by and wedded to the stern Presbyterian working men Scotland excelled in, were fantastically strong copers, but they kept their emotions in check. Life taught them not to expect too much. They kept house at a time before bathrooms or washing machines or detergents; they raised children on meals magicked from very small incomes; they toiled from early to late as slaves to men like John Leckie – and he was a saint compared with most men, for he did not drink. Women like Cis were not schooled in any kind of delicate niceties and displays of emotion; kissing and hugging were unheard of. Hers was a loving household but one devoid of displays of physical affection. Until her old age, even a pat on the head was a very unusual thing.

Decades later, when Gregor went into show business, everyone was hugging and air-kissing each other all the time – the whole luvvie thing. Recalling this, he flaps his hands in comic revulsion. ‘Christ, I couldn’t cope, I couldn’t bear it! It was like, “What are you doing? Get away from me! There’s a barrier here, can’t you see it? Come on, what’s going on? I’m a Scotsman. Please don’t do that, you’re making me feel very uncomfortable.”’

At the time, locked in the intensity of his one-to-one relationship with his new mother, Gregor had little or no concept of the needs of other members of the Leckie family. All children, but especially needy ones, are entirely self-centred. Instinctively, they manipulate the person who gives them most succour and affection. From his perspective, he clung to Cis for emotional and physical survival. Looking back, he realises he caused tensions but he now understands why.

I don’t think I was a very nice little boy. To be honest, I think I was a right little pain in the arse. Looked nice, you know, lots of nice blond curls and all the rest of it; nice to look at, but not nice to spend any time with – the little shit in the Ladybird shorts. I don’t think the rest of the family liked me very much because I was so desperate to gather in every bit of affection that Cis could give me.

Though loved and secure, he was at the same time an outsider who watched and remembered. When John Leckie was around it was best for Gregor to play in the corner. In the silence he absorbed and listened. The other male role model in his life at that time was Uncle Wull, a man every bit as eccentric as John Leckie, both of them rich fodder for the child who would one day put their idiosyncrasies to good use. Wull was a bit simple. Gregor liked him. Cis’s half-brother, he was much older and illegitimate – her mother had had a child out of wedlock that nobody knew about. Cis and her siblings didn’t know of his existence until much later, when Granny died, and he was then taken under Aunt Agnes’s wing. During the week he lived with her in town and went to work at the Parks Department in Glasgow; on weekends he always came to stay at Neilston to be fed and looked after by Cis.

Wull would be classified as special needs now. Back then he was just a bit different and everyone accepted it. He was kind to young Gregor too. Wull mostly communicated by grunting. He’d take out a 10-shilling note and make lots of guttural noises, showing the note to the boy before he folded it up, reached over and squeezed it into his hand. Gregor knew not to say anything – it was between the two of them, an unspoken West of Scotland thing, ‘Don’t tell your mother.’ According to family legend, Wull only spoke once or twice. Every year, when the relatives arrived on their annual visit to Aunt Agnes from the Borders, Wull would open the door and distinctly grunt: ‘Are ye back again?’

He was once handed a box of Milk Tray and Aunt Agnes said to him, ‘Remember and give your cousin one.’ And the cousin got one, just one chocolate. No one else got any. That was Wull; he was very literal.

People would find him jobs. Cissie used to send him across the road to Miss McMaster’s, an old, retired matron, and he would cut her hedge for her. He cut it with a manual hedge trimmer, a vicious-looking machete-like blade on a pole, which he would flail around wildly, grunting. He was good at that job.

Uncle Wull was small, square-jawed. He didn’t impress John Leckie, who sat in his usual spot by the fire and ignored him, dismissed him with his silence. Wull didn’t seem to notice. Both men had idiosyncratic toilet habits, which fascinated the small boy. Way before his time John Leckie was the master of recycling. After he had been to the outside loo, he would come back in, carrying the pieces of newspaper used to wipe himself, and throw them on the living-room fire because he didn’t want to block the plumbing. And he wouldn’t waste money using Izal toilet paper. That was the way he lived.

Sometime in the 1960s the family abandoned the outside loo and had a bathroom and a toilet installed inside the house, which caused a lot of excitement. That was when the bath arrived, insisted on by the girls. All the new facilities were on the ground floor, but upstairs there was still nothing. Gregor watched, wide-eyed with glee, as Uncle Wull would come gingerly downstairs in the morning, carrying a large Ostermilk tin in front of his body.

‘Full to the brim of pish.’

That was just the way it was, no questions asked. The child stored away the cameos and memories with relish. Besides, at that point in his life Gregor had decided he was going to be a church minister, opening his heart to the frailties of all mankind when he grew up. Apart from John Leckie, who never left the fire, the entire family was very churchy. Gregor’s big sister Margaret certainly was, in a vaguely intellectual way, to the extent that she would attend lectures by the famous Scottish theologian Professor William Barclay. There would always be a copy of Life & Work, the Church of Scotland magazine, lying about the house. The Leckies’ home was next door to the manse, where the minister Robert Whiteford and his family lived. Reverend Whiteford, a striking man with a big shock of hair, cut an imposing figure to a small boy. Two of his four children, John and Bobby, were the same age as Gregor, who often played with them in the large manse garden. They had bikes and he didn’t, although he was desperate for one, and he once got into terrible trouble with Mrs Whiteford for stealing one.

‘It was Bobby’s bike. I took it for a joy ride and then parked it at my house, intending to keep it. It was lunacy – because we were near neighbours, but I thought I would never be discovered.’

Religion was an optionless situation. Gregor attended Sunday school and he went to church; he loved Robert Whiteford who, although he didn’t understand half of what he was talking about, gave a very good blessing too.

Gregor Fisher lifts his hand and his diaphragm and slows his voice to its strongest and ripest. ‘“The blessing of God Almighty, Father, Son and Holy Ghost be with you this day and for evermore.” And I went “Ooh” and shuddered. I thought it was all rather fabulous. I think I’d have made a good Catholic, actually – do y’know what I mean? It was the theatricality of it that got me. I just thought it was “Oh, this is marvellous! Gimme some of that!”’

On the wall in the Sunday school there was a big picture of a kindly Jesus in white robes. Gregor loved the robes and the queue of all the children of the world in their national costumes snaking off into the distance, waiting for their chance to sit on Christ’s knee. In the picture he was holding a little black child and Gregor decided that this was what he wanted to do when he grew up: be a missionary. That was the job for him, thank you very much. He started praying to be allowed to be one. Gregor was for a while very busy with his prayers.

I was usually asking things like, please make me as good-looking as Bobby Thorpe or somebody else who was the leader of the gang, because that’s what I wanted to be. I seemed to take to prayer. Did a lot of it. I think there was plenty of guilt involved when I was a child, I always felt guilty about something. Hellish guilty about the fact that I wasn’t very good at school or even Sunday school … you had to learn by rote the Beatitudes, or the Ten Commandments, and you would get a little badge. The Reverend Whiteford would test you on this – it was almost Victorian.

So those were abiding memories, walking up the hill to church holding Cis’s hand. With her faith, and her Sunday hat and her huge heart. She was the patron saint of lost people, blessed were those she found. Cis looked after the simple Wull; certainly she rescued Gregor, and she also rescued old dogs and nurtured chickens by the fire. She would never see anyone, or anything, in trouble.

Some family secrets remain buried forever, with the complicity of everyone involved. Others, however, are shared at a certain point. It was inevitable that there would come a time when Gregor would question why his mother was so old and where, if she hadn’t given birth to him, had he come from, that day in the snow? Given the bond between them, this was always going to carry a lot of emotional freight. When it did happen, it was devastating, leaving both in distress. This was the only time Gregor ever rejected his mother; shut her out from him, closed the door on her love.

It was during one of those scones-and-jam family suppers when the mood had lifted because Mr Leckie had gone to work. There must have been a christening in the family because it was the subject of discussion. Churches, godparents, babies … Cis, Margaret and Una chatting.

Out of the blue, Gregor, unthinking, opened his mouth.

‘Where was I christened?’

An awkward, loaded silence fell over the room; an ear pop of tension. Sensing something, and never slow at coming forward, Gregor repeated his question. Immediately the subject was changed. One of his sisters offered him another scone, his mother chipped in with a change of subject. ‘Uh-oh,’ he thought. Preoccupied with himself, like all 14-year-olds, he picked up on the evasion, the awkwardness in the room. There was a mystery, some secret being withheld from him. Something that pertained to him, which everyone else was party to.

Nothing more was said and he went to bed as usual. Then came a knock on his door – an unusual occurrence because it was the sort of household where no one locked or knocked on doors. His mother came into the room.

‘You’re adopted,’ she said.

She stood there awkwardly, looking at him, unsure what to do next. It was the classic, blunt-edged West of Scotland way of doing things. In the 1960s no one was schooled in communication and child psychology; no one read manuals on how to discuss sensitive issues with children. Unlike today, there weren’t numerous books and websites on how to deal with an adopted child. There were few social workers, hoops to jump through or guidelines to follow. What followed was a moment of most extraordinary drama. Cis was not given to physical demonstrativeness, but she reached out with her hand and patted her beloved son on the head.

Not once. Twice.

A single pat was unheard of. Two was a sign of almost uncontrollably high emotion. Cis was obviously as moved as she was uncomfortable.

‘We look after you now, you know. We wanted you, we love you,’ she muttered.

And she turned and left the room.

We’re on our first expedition together, Gregor Fisher and me. A most unlikely Johnson and Boswell, more Dastardly and Muttley. It must surely be a comedown for him – usually he’s in a Mercedes. This time he’s in my silver VW Polo; a man both cheery and wary, a passenger I barely know. I wonder what he’s thinking. I know more about his ancestors than him, the living flesh and blood. Some months ago he had approached me out of the blue, through a mutual friend, because he wanted, finally, to pin down the story of his life.

We’re heading up the hill into the village of Neilston, me driving, him navigating.

Gregor is telling me about what happened when Cis died, in 1983.

‘She left me some money.’

He is silent for a bit.

‘I’ll never forget it – it said in her will, “I leave so much to my daughters and I leave so much to Gregor Fisher, who lived with me.”’

His voice catches. I suddenly realise he’s crying.

‘Why did they have to say that? “To Gregor Fisher, who lived with me”.’

Tears are running down his cheeks. She was his mum but he wasn’t her son. Even beyond the grave he wasn’t allowed to be her son. The authorities wouldn’t even give him that comfort: a rejection from the woman who never rejected him.

‘It’s just legal language,’ I say, desperate to console him. ‘Bloody lawyers, they have to say these things just so. A technicality.’

He’s wiping his face with a hankie.

‘I know that, I just can’t forget it,’ he says. ‘Gets me every time.’