Читать книгу Crime of the Century - Gregory Ahlgren and - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER III

ОглавлениеThe flight of the Spirit of St. Louis has been forever imprinted in the American psyche. An event which now seems commonplace was wondrous and daring in 1927. After 33 and onehalf hours in the air, Lindbergh touched down at Le Bourget field in Paris. The flight shrunk the oceans and all of humanity and it coalesced American pride in its emerging technological power.

In 1990, "Dear Abby" devoted a special column to people who remembered the Lindbergh landing. "I was a student at the Sorbonne," a reader wrote, "when the radio announced that Lindbergh had been sighted over Ireland and would be landing in Paris in a few hours. A classmate and I took a bus to the airport. We were among the thousands of spectators restrained behind a wire fence. When Lindbergh landed, the crowd pushed the fence over and ran out on the field. The police had to rescue him from his enthusiastic admirers."

Another wrote, "I was at the theater when an announcement was made at intermission that Lindy had landed safely in Paris. Everyone cheered and left the theater to join a wild celebration in the streets, dancing and hugging strangers! The next day, Lindy was honored with a huge parade down the ChampsElysees. It was one of the highlights of my life. I am 93 now, and an American citizen living in New Jersey."10

His reception throughout France, Europe and particularly upon his return to the United States was no less enthusiastic. His first night in Paris, Lindbergh slept at the home of the United States Ambassador to France. Soon after, he met the President of France, addressed the French Assembly, was received by King George V of England, and given accolades the world over for his feat.

To get him home, and America wanted him home fast, President Calvin Coolidge dispatched the United States cruiser Memphis under the command of Admiral Guy Burrage to Cherbourg where it picked up Lindbergh and his plane. The Secretary of War, Dwight F. Davis, had already arranged to promote Lindbergh to the rank of Colonel in the Air Corps Reserve, a title Lindbergh would cling to in the ensuing years.

He was exceedingly tall, and his height seemed to amplify his solitary nature. He captured the imagination of a nation with his stoical and fearless nature, and he appeared bright, even if he was somewhat aloof and lonely. He was quiet and reserved, not given to boastful behavior. He was, in short, a person whom everyone could romanticize as the adventurer, who embodied all that we wanted him to embody. He became an American Hero.

The country could forgive him his idiosyncrasies. It would shower him with admiration, pridefully boast to the world of his name, and, in his presence, defer to him. This would later include law enforcement officers who were involved in the investigation into the disappearance of his first born son. As America's Hero he quickly became acclimated to deferential treatment.

When he stepped off the ship at Alexandria, he was met by his mother. She had been brought to Washington as the guest of President and Mrs. Coolidge. From there he joined a parade which led him to a huge stage erected at the Washington Monument. Waiting on the stage was the President of the United States, who gave a long speech extolling the virtues of a young man who, only a few days earlier, had been a virtual unknown.

Lindbergh responded with these words. "On the evening of May 21, I arrived at Le Bourget, France. I was in Paris for one week, in Belgium for a day and was in London and in England for several days. Everywhere I went, at every meeting I attended, I was requested to bring home a message to you. Always the message was the same. `You have seen,' the message was, `the affection of the peoples of France for the people of America demonstrated to you. When you return to America take back that message to the people of the United States from the people of France and of Europe.' I thank you." And Lindbergh sat down. It is the shortest known response ever given to a Presidential speech.

Lindbergh was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and for the first time in an action unconnected with war, the Congressional Medal of Honor, the United States' highest award for bravery for a person serving in the Armed Forces. The French presented him with the French Legion of Honor, and the British with the Air Force Cross. He received thousands of offers to endorse products, lucrative job offers, gifts, proposals for marriage, and several million letters, telegrams and cables.

On June 13th he traveled to New York City and was given a parade attended by what is still believed to be the largest crowd in New York City history. Some four and one half million people turned out to see him in the motorcade. In a speech at City Hall, Mayor James J. Walker looked up from his script at the end of his long discourse and said, "Colonel Lindbergh, New York City is yours I give it to you. You won it."

The Wright Aeronautical Corporation had assigned a corporate public relations specialist named Dick Blythe, along with an assistant, Harry Bruno, to handle the Colonel's public relations, and to help sort through the offers which were pouring in. Lindbergh had signed contracts with Mobile Oil, Vacuum Oil, AC Spark plugs, and Wright before departing. Each contract averaged $6,000 and the companies were now cashing in. Each could have afforded to pay him much more after the flight, and many more wanted his endorsement. On June 16, 1927 he was awarded the Orteig Prize and given the $25,000 at a small ceremony. Interestingly enough, Raymond Orteig's committee had to bend the rules to present the money. The published rules had stated that in order to qualify, sixty days had to lapse between the time the entry was received and the time the flight took place. It had not. Even though the rules had been well publicized in advance everyone had agreed that they could overlook it "in this case." After all, Lindbergh was special.

He wrote an account of his flight called We, which earned him $100,000 in royalties. In the summer of 1927 he was also paid to take a crosscountry tour. Flying the Spirit of St. Louis he made stops in all 48 states, flying through all weather conditions and missing only one date in Portland, Maine. In every location he was mobbed, particularly by women. He was, after all, perceived to be the most eligible bachelor in the world, though anyone who took the time to inquire further found that Lindbergh held most women in disdain.

Harry Guggenheim, who had established the Foundation for Aeronautical Research, was the financial backer of Lindbergh's crosscountry flight. Known as "Captain Harry," Guggenheim was a wealthy philanthropist who was more than willing to provide Lindbergh a safe haven from the crowds and press by offering him a permanent room at his mansion on the north shore of Long Island. There Lindbergh rubbed elbows on a regular basis with influential people such as Thomas Lamont, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. the publisher George Palmer Putnam, Herbert Hoover, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., and a banker named Dwight Morrow.

These were the power elite of society mostly Republicans. Dwight Morrow was also the Ambassador to Mexico and a prominent Republican whose name was already being touted as a possible Presidential nominee. When Ambassador Morrow invited Lindbergh to come to his home in New Jersey and later to Mexico, Lindbergh readily accepted.

Morrow's New Jersey home was a sprawling manorial mansion in Englewood. He was married, and the father of a son and three daughters, one of whom was Anne Spencer Morrow.

Lindbergh used the invitation to Mexico to promote a South American tour, and to begin it, announced that he would fly nonstop from Washington to Mexico City in December of 1927.

Upon arrival Lindbergh found that Morrow had arranged a greeting by the President of Mexico and he was widely feted wherever he went. He stayed at the Ambassador's home during the Christmas holiday with his mother, who had also been invited by the Morrows, and who had reluctantly come.

While staying there he spent time with the three daughters. It was reported that he got along very well with Constance, who was younger than Anne and still attending an exclusive boarding school, Milton Academy, in Milton, Massachusetts.

Anne arrived from Smith College shortly after Lindbergh's arrival. In 1927 she was twenty-one years old. She was intelligent and sensitive but also extremely shy and introverted. Although she was not quite sure of herself around Lindbergh, she was definitely attracted to him.

In her diaries, Anne wondered whether Lindbergh would be more attracted to her older sister Elisabeth, or her younger sister Constance, with whom he seemed more at ease and able to engage in conversation. The pair seemed to have developed a natural rapport.

Dwight Morrow invited him to spend more time with them at their summer home off the coast of Maine. Later that year Lindbergh quietly began courting Anne Morrow. He asked her to go flying with him and this became his regular method for seeing her. Anne's diaries reveal mixed emotions about Charles Lindbergh and she wrote that he was "terribly young and crude in many small ways."11

Lindbergh maintained his tumultuous relationship with the press. He responded angrily at several newspaper accounts which reported that he was "getting a swelled head," and in a huff declared that henceforth he would only see reporters when it had to do with aviation.

Unless of course it furthered his own interests, as it did on October 3, 1928 when he released to the press a telegram he had sent to Herbert C. Hoover, then the Republican nominee for President:

The more I see of your campaign the more strongly I feel that your election is of supreme importance to the country. Your qualities as a man and what you stand for, regardless of party, make me feel that the problems which will come before the country during the next four years will best be solved by your leadership.

The newspapers continued to track Lindbergh's activities, reporting on his flights to further causes in aviation. They also tracked the possible link between Charles and the Morrow daughters. At the end of April, 1929, the New York Times had daily stories on the fact that Mrs. Morrow and her daughter Anne were on their way north by train, traveling from Mexico to New Jersey. What did not receive much attention however, is that Constance Morrow had received a letter at the Milton Academy threatening violence against her unless a ransom was paid. She was also instructed not to tell the police. The amount demanded as payment was $50,000 the same amount which, almost three years later to the day, would be asked for the Lindbergh baby. The official records of the Milton, Massachusetts Police Department reveal that on April 24, 1929 at 10:20 p.m. "A.H. Weed, 150 School Street brought to station a letter received by Constance Morrow, Milton Academy, demanding money under threats of violence. Miss Morrow lives at Hathaway House. Sergeant Shields sent to detail Officer Lee guard Hathaway House tonight. Mr. Weed will bring letters to station tomorrow after he had had a copy of it made."12

Two weeks later a followup letter arrived instructing her to put the $50,000 in a certain size box and to place it in the hole in the wall behind a nearby estate. By this time the police were involved and the whole Morrow family, including future inlaw Lindbergh, knew of their involvement. An actress placed an empty box in the designated hole and the police staked it out. No one picked up the box.

Charles Lindbergh and Anne Spencer Morrow were married May 27, 1929 in a small ceremony at the Englewood, New Jersey home of the Morrows. They left for what they had hoped would be a quiet honeymoon on a yacht moored off the east coast. But Charles Lindbergh was the most famous man in America, and now there was a Mrs. Lindbergh. The media attention focused on the couple. Anne's diaries are particularly revealing about their relationship.

Although there is no doubt she was infatuated, there are many indications that she considered Charles her intellectual inferior. She expressed disgust with his "school boy pranks," which he continued to pull on a regular basis. She also chafed at the role of his faithful companion, there only to service his needs. It did not go unnoticed that Anne was expected to learn new skills in order to fly with Lindbergh and that she was the one carrying equipment from the plane when they landed while he remained the focus of attention.

Lindbergh himself certainly had a strange way of describing his courtship, marriage and relationship with Anne, the person with whom he had decided to spend the rest of his life. In his autobiography he wrote:

On May 27, 1929, I married Anne Spencer Morrow. From the standpoint of both individual and species, mating involves the most important choice of life, for it shapes our future as the past has shaped us. It impacts upon all values obviously and subtly in an infinite number of ways.

One mates not only with an individual but also with that individual's environment and ancestry. These were concepts I comprehended before I was married and confirmed in my observations over the years that followed. 13

This rather clinical description of "finding a mate," contrasts markedly with Anne's poetic descriptions of life, her trials, aspirations, hopes and dreams for the world. Anne Morrow was a deeply sensitive and caring person, who experienced and suffered much in her life.

After their brief honeymoon, Charles and Anne went to work promoting aviation. Charles taught Anne to fly. She also took courses on navigation, learned how to operate a wireless from a plane, and flew with him on many crosscountry flights. Harry Guggenheim announced that he had placed Lindbergh on a retainer for $25,000 for the Guggenheim Aeronautical Foundation so that Lindbergh could promote air travel as a safe, efficient, and effective means of transportation.

In the fall of 1929 Anne's suspected pregnancy was confirmed by her doctor. Nevertheless, Charles expected Anne to continue to accompany him on flights around the country. Lindbergh had announced to the press, with whom he had grown aloof and curt, that he and Anne would break the record for a transcontinental flight between Los Angeles and New York. He had a new plane specially built in California, which he and Anne picked up. They named the plane Sirius, after the bright star in our galaxy.

While in Los Angeles, he introduced Anne to Amelia Earhart at the home of Mary Pickford. Ever since her flight across the Atlantic in 1928 Amelia Earhart's fame as an aviatrix had grown. Newspapers had given her the nickname of "Lady Lindy," a title which she later confided to Anne she did not care for.

Nor, frankly, did she seem to care that much for Charles Lindbergh. After spending about four days with him and Anne, she told her soon to be husband, George Putnam, that Lindbergh was an "odd character." In Putnam's 1930 biography of Earhart, Soaring Wings: A Biography of Amelia Earhart, Putnam recounts Amelia's story about socializing with Anne and Charles that week at the Hollywood home of Jack Maddux.

Anne, the Colonel and AE (Amelia Earhart) were fellow guests at the home of Jack Maddux in Hollywood. One night they were sitting around close to the icebox. Anne and AE were drinking buttermilk. Lindbergh, standing behind his wife munching a tomato sandwich, had the sudden impulse to let drops of water fall in a stream on his wife's shoulder from a glass in his hand.

Anne was wearing a sweet dress of pale blue silk. Water spots silk. AE observed a growing unhappiness on Anne's part but no move toward rebellion, not even any murmur of complaint. AE often said that Anne Lindbergh is the best sport in the world.

Then Anne rose and stood by the door, with her back to the others, and her head resting on her arm. AE thought, with horror, that the impossible had come to pass, and that Anne was crying. But Anne was thinking out a solution to her problem, and the instant she thought it out, she acted upon it. At once and with surprising thoroughness.

With one comprehensive movement she swung around and quite simply threw the contents of her glass of buttermilk straight over the Colonel's blue serge suit. It made a simply marvelous mess!

Odd indeed. Imagine yourself in such a scene with your spouse. What would your reaction be to such a cruel and embarrassing moment, in front of virtual strangers, in someone else's home? Such were the manifestations of Charles Lindbergh's "practical jokes."

It fitted a typical behavior pattern inherent in all of his "jokes." Lindbergh used his "jokes" to control people whose behavior he wished to alter. He did not want the sergeant to bother him, the cadets to harass him, Love to socialize with women or Gurney to drink alcohol. He performed his jokes to punish them for their behaviors.

It is unknown what prompted him to dump a glass of water on his wife's head in front of Amelia Earhart. But it is known that Lindbergh had an extremely sexist view (even by 1929 standards) of women and accorded them little respect. Anne Lindbergh was not only very bright, she was extremely well educated and clearly his intellectual superior.

Amelia Earhart was more than an accomplished flyer. She was a leading American feminist who promoted her political beliefs by demonstrating that women could perform equally to men.

Anne and Amelia were engaged in an intense discussion. If Lindbergh perceived Anne becoming swayed by Amelia's political belief on women, then the water dumping fits a classic pattern.

Shortly thereafter the new plane was completed, and Anne and Charles left for their return flight across the country. Charles was determined to set the new crosscountry speed record in Sirius. A storm system gathered almost immediately after their departure from California, forcing Lindbergh to fly extremely high over the Rockies and throughout the flight. They had no oxygen with them. Anne was seven months pregnant.

At several points during the flight Anne thought that she would plead with Lindbergh to land the plane, but did not. It was the worst flight she had yet endured with her husband and it caused her to be so sick that when they landed in New York she had to be carried from the plane by stretcher and rushed to the hospital.

Since the press was waiting for Lindbergh at the airport to report on his efforts to break the cross country speed record, Anne's apparent sickness was reported the next day in the newspapers. Lindbergh angrily denied that Anne had been ill, and his office castigated the press for reporting such. However, years later Anne herself admitted in Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead that the flight had caused her great misery, particularly in her condition. Today any physician would strongly advise against an expectant mother, seven months pregnant, flying without oxygen for a prolonged period. Oxygen deprivation to a near full term fetus is quite dangerous.

In May of 1930 Anne moved in with her parents at Englewood to await the birth of their first child. The country, and most certainly the press, was greatly interested in the arrival of the first born of Charles Lindbergh. Several newspaper accounts drew a parallel between awaiting the arrival of the Lindberghs' baby and the British anticipating the arrival of an heir to the throne.

But when the baby, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, III, was born on June 22, 1930 (which was Anne's 24th birthday), the world was kept waiting two weeks before Colonel Lindbergh would release either the name or photographs of the baby. The family reported that both mother and child were doing very well, and that the baby was "normal" in all respects. Later it was disclosed that the child had two overlapping toes on one of his feet, but other than that was "healthy and normal." This description of the baby as "healthy and normal" appears often in published accounts of the baby's birth, during the time of the kidnapping, and of his death. It was often rumored, though never established, that there was something "wrong" with the Lindbergh baby.

Colonel Lindbergh developed a pattern during the beginning of his marriage, and after the birth of his son, which he followed for most of his life. He would travel frequently, spending little time at home. In July of 1930, his business affairs were growing, and he was placed on the "preferred customer" listing at J.P. Morgan's Bank, which enabled him to buy choice stock at below market value. Since his interest in a number of airline companies was growing, a family friend of the Morrows, Manhattan lawyer Colonel Henry C. Breckinridge, became Lindbergh's advisor.

He also struck up an association with Dr. Alexis Carrel, a Nobel scientist and French doctor who was working at the Rockefeller Institute in New York. Lindbergh often joined Carrell at the Institute and helped him develop a perfusion pump to keep organs alive. Its designs were studied later during the development of the artificial heart. Carrel was a strange individual who wore a black hooded robe in the laboratory and insisted that all of his lab assistants do the same. He had won the Nobel Prize in 1912 for his work on suturing blood vessels during surgery instead of destroying them. But as he grew older, his views became more radical, and he wrote papers and published articles on subject matter well beyond his expertise.

In a published book entitled, Man, the Unknown, Carrel postulated that "dark skinned people" were part of the "lesser races" because of their high exposure to sun light, as opposed to the Scandinavian races which did not get exposed to as much light. Lindbergh was fascinated with Carrel's views on these and other subjects, and after he and Anne fled to Europe following the trial of Hauptmann, lived for a time near Carrel's island home off the coast of France.

In the spring and summer of 1931, the Lindberghs prepared for a northern surveying flight to the Orient. It was hoped that by doing so a commercial air route could be developed since this seemed to be the shortest route. For this trip the Sirius was equipped with retractable landing gear and pontoons as most of the landings would be on water.

It was also a route filled with hazards. Water landings, even under the best of circumstances, could be extremely dangerous. Lindbergh was widely criticized for the route he had charted. Several prominent explorers and experts on the Arctic advised him that his "straight line between two points" approach to his charted course was filled with unnecessary risk taking, and that by slightly altering his course he would avoid many of the more extreme hazards. He refused. Risk taking was welcomed by Colonel Lindbergh. Hadn't he, after all, piloted in all sorts of weather, crossed the Atlantic alone, wing walked, completed a double parachute jump on his first leap from an airplane, and survived several crashes? One of the scientists reminded Lindbergh, however, that this time he was taking his wife on the trip.

Of the many dangers encountered several could have been avoided. After departing Point Barrow, Alaska, the northern most point of the trip, he was forced to land due to a fuel shortage. He did so at an inlet called Shishmaref near Nome, and had greatly miscalculated the time of sunset. He set down in near darkness with fog approaching, an extremely dangerous combination for water landings. Not carefully tracking the hours of sunset near the Arctic Circle was a mistake commonly made by inexperienced pilots. Later the Arctic expert and flyer John Grierson publicly criticized Lindbergh in a letter for taking this kind of a risk. He asked why he hadn't checked sunset time at Nome before leaving Barrow. Lindbergh defended himself, but was not convincing in his arguments.

While flying south from the Soviet Union to Japan, Lindbergh had to land between very jagged mountainous peaks in dense fog. For Anne, it was the most terrifying landing she had ever experienced, describing it as "a knife going down the side of a pie tin, between fog and mountain." She wondered whether her husband would then say "It was nothing at all."14

There were three forced landings of this kind during their trip which effectively ended in China. The Lindberghs had been gone since July 31, 1931. Anne missed her baby, who was being cared for by her parents and their staff. When the plane was damaged in China at the beginning of October, she was frustrated and homesick, and wanted to return as quickly as possible. When a cable arrived in Shanghai on October 5, 1931 telling her that her father had died from a brain hemorrhage, Lindbergh canceled the flight, ordered the plane shipped back to San Francisco, and booked passage on the first ship home. They were reunited with their son on October 27th. When Anne Morrow Lindbergh's account of this journey was published in her first book entitled North to the Orient, she established herself as a first rate author. She would go on to become well published.

Dwight Morrow's death at 58 was a shock to his family. Anne wanted to stay with her mother, to be close to the family during a very difficult period. While Anne enjoyed a very close relationship with her mother, this was not the case between Charles and Mrs. Morrow. During his later antiwar and proNazi activities, Anne's mother publicly criticized her soninlaw for his "unAmerican" behavior. Dwight Morrow had once remarked, "what do we know about this young man Lindbergh?"15

Though livable, their new home in Hopewell, New Jersey was not complete. On weekends, the Lindberghs would stay there, along with the Whatelys and the Lindbergh dog. Betty Gow would not accompany them to Hopewell. This was her time off, and it gave Anne a chance to have time alone with the baby.

Lindbergh settled into a routine of traveling into New York City on Monday mornings for his work with the airline. Later in the day Anne and the baby would return to Englewood. Colonel Lindbergh had found that when he stuck to a regular pattern, the press was far less likely to bother him. He closely guarded, and kept secret, any variation in his schedule.

Such was not the case, however, on Monday, February 29, 1932. Charles' telephone call to Anne, instructing her to stay over an extra day, reflected a clear deviation from their usual pattern.

The Colonel himself stayed over Monday night in Englewood. On Tuesday morning he telephoned Anne and told her to stay over in Hopewell one more night, again citing the weather and the baby's cold. He left other specific instructions about the baby, and said that he would drive home to Hopewell from work that evening. According to Anne's testimony at the Hauptmann trial, Charles honked his horn in the driveway upon his arrival at 8:25 p.m. that evening. In a letter the next day to her motherinlaw Anne wrote that, "C was late in coming home."16 The arrival was approximately 35 minutes after Betty Gow had last checked the child.

Lindbergh never explained why he had arrived home late that evening. At the trial he explained his occupation as "aviation" and made vague reference to having been in New York that day on business. No further details or explanation were ever offered by him or elicited on crossexamination concerning his own actions that day.

The situation in Hopewell was ripe for a Charles Lindbergh "practical joke" against Anne. She was alone, cutoff from her mother, family and the other staff at Next Day Hill. Even Betty Gow was not with her. During weekends she alone was responsible for the care of the child.

If Lindbergh had kept to his usual schedule he would have arrived home at approximately 7:45 p.m. That would have allowed him plenty of time to pull in the driveway approximately 100 yards from the road, (but still out of sight of the home) and park his car. Since he was the owner of the house and discovery of his "prank" at that time would not have been damaging to him, and since he knew that no one else was expected, there was no need to park along the road and forsake the easier access the driveway afforded. He would have had plenty of time to remove the child through the window with the warped shutters in preparation for some sort of later dramatic presentation of the child. Perhaps he planned a front door arrival with the announcement, "Look who I had with me in New York all day."

For a person who had made a career of wing walking and hanging from airplanes by his teeth, who was unfazed by a double jump on his first parachute drop, climbing a ladder at night was nothing. For a person who would carry a bed up to a roof at night, carrying a child down a ladder would be easy.

But unlike with the sergeant's bed, this time Lindbergh miscalculated. The ladder broke and the child was dropped to the granite ledge below. The impact crushed his skull, causing instant death.

Lindbergh would have immediately grasped his quandary.

To reveal the truth, to go to the front door and tell his wife, "I was taking our 20 month old child out of his second floor window over my shoulder and down a ladder in a windstorm at night as a joke and I dropped him and here's your dead baby," was unthinkable. He would be a fool, not only in front of his wife and inlaws but in the eyes of the whole world. All he had accomplished for his own reputation would be gone. In one instant he would be transformed from the American Hero to the American Buffoon. Charles Lindbergh would never allow it.

He had begun this prank as a kidnapping and he would see it through as such. There were enough ransom kidnappings that this one would be plausible. He had lived in Mount Rose while supervising the construction of the Hopewell house and knew the woods there. He would drive there, leave the body, and return to play out the role of the father as victim in a real kidnapping.

Lindbergh could have gathered up the body, retreated down the driveway, bundled the body into the rear of the car, backed out of the driveway, and driven off. Once in Mount Rose he would have to leave the body hurriedly. He could not take a chance on any delay which would be occasioned by digging a grave. Nor, since he had not planned on having to dig one, would he have had any shovel or similar implement with him. He could not go too far, as he would want to minimize his own tardiness in arriving home. A half hour delay would be tolerable.

The spot where the body was found was less than three miles south of Hopewell, in the opposite direction from New York City. Lindbergh parked by the side of the road and brought the body a short distance into the woods where he lay the child in a depression on top of the ground.

He could easily return by 8:25 p.m., when he would honk his horn as he drove up the driveway to assure that everyone in the household would notice this arrival.

Lindbergh now merely had to do five things. First, he had to make sure that he did not find the empty crib, for if he did, his past history of pranks and in particular his having previously hidden the child would focus suspicion right on him. This would mean he could not enter the nursery until the child was discovered missing by someone else.

Two, he had to set the time of the "kidnap" so that it occurred when he had an alibi with the person most likely to suspect him: Anne herself.

Three, to complete the kidnap scenario he had to get a ransom note into the nursery. This would be especially hazardous since he could not afford to risk entering the nursery until after the baby was discovered missing.

Four, he had to do something about the "fingerprint problem" once the police were involved. Since the prank had never been intended to go this far he would not have bothered to wear gloves during his initial window entrance to the nursery. But now that the child was dead and he was going to continue with a kidnap story the police would be involved. Lindbergh knew that the first thing they would do would be to dust the note and nursery for fingerprints. He had to make sure that his prints were not on the note he would write, a task he could easily accomplish.

However, the problem with the nursery was more difficult. A dusting of that room would not only reveal the lack of any stranger's prints but would also reveal Lindbergh's on surfaces where they would not ordinarily be expected including the window, windowsill, sash, etc. All such traces would have to be removed. The room would have to be wiped before the police arrived.

Five, he had to consistently play the role of the father as victim and make sure that suspicion focused anywhere but on him.

If he followed those five steps faithfully he would be all right. He had pulled off the other stunts, he had flown blind into blizzards over Chicago and parachuted to safety, he had cut his engine and skimmed the Mississippi before restarting, he had flown solo across the Atlantic, in what, by contemporary standards, was not much more than a motorized hang glider. He could pull this one off too.

The first step, to avoid finding the empty crib, was easy. Upon reentering the house shortly after 8:25 p.m. he immediately realized that the disappearance had not yet been discovered. He went upstairs and washed up. However, even though the bathroom was adjacent to the nursery he did not enter it to "check" on his child.

He returned downstairs where he and Anne ate supper. Afterwards he steered Anne into his study directly under the child's nursery.

It was here at approximately 9:15 p.m., while the wind continued to blow outside, that Charles interrupted the conversation by asking, "What was that?" Anne had not heard anything. The Whatelys never heard anything. Betty Gow never heard anything. The high strung terrier Wahgoosh never barked.

Only Charles Lindbergh claimed to have heard something, a sound he later described alternately as a snapping sound or as wooden crates falling. He knew the wooden ladder lay outside in the mud with a broken rail. He needed to establish the time of the break to a moment when he had an alibi. He did, and the second part of his plan was complete. At approximately 9:20 p.m., Anne and Charles went upstairs where they spoke briefly in Anne's bedroom. Charles left and drew a bath in the upstairs bathroom. Again he did not use the occasion to enter the adjacent nursery. Anne remained in her bedroom writing.

The bath was important for Charles. It allowed him to assure that any remaining tell tale evidence was removed from his person and also gave him additional time to collect his thoughts.

After his bath, Charles descended to his study where he remained alone with his pens, his writing paper and his envelopes. He had to complete the third part: the ransom note. Yet he was in a tough situation because he dared not risk planting the note until after the disappearance was discovered.

At Hauptmann's trial the chief handwriting expert for the prosecution, Albert Osborne, testified that the original nursery note had been written in a disguised hand. Lindbergh wrote the note, disguising his handwriting all the while.

South Jersey was heavily populated by German immigrants. To draw attention away from his household, Lindbergh attempted to make it appear that the note had been written by one. He used some simple German words ("gut" for "good") and phonetically spelled other English words as he believed a German immigrant might pronounce them. A German struggling with the English language often says "d" instead of "th" as the "th" sound does not exist in German. For instance, the English definite article "the" in German is "Der", "Die" or "Das", depending on the gender of the following noun. In conformity with this, the note used the word "anyding" instead of "anything." What is patently false is that the use of a "d" sound instead of the English "th" is an enunciation problem. A German would not spell a word with a "d" instead of a "th"; it is not the case that he thinks that the word is spelled with a "d"; rather he knows it is spelled with a "th" but he simply can not pronounce the "th." The writing of "anyding" is simply the attempt of one trying to imitate a German immigrant's speech.

The European method of placing the monetary symbol "$" after the numerals was also employed. And lastly, Lindbergh used the plural "we" to make it appear that the kidnapping was the work of a gang.

Lindbergh then sealed the envelope, after making sure his prints were not on it or the note, and awaited his opportunity to begin his role as the victim. That opportunity arrived with Betty Gow's 10:00 p.m. entrance to his study asking if he had the child.

It must have been nerve racking, waiting for the knock on the door he knew would come. When it did he sprang into action almost too quickly and thereby almost made a fatal mistake. Fortunately for him, no one at the time noticed.

He quickly bounded up the stairs to the child's room, the note safely hidden on his person. His wife and Betty Gow looked at the empty crib. He knew that it was time to get everyone immediately focused on an outside kidnapping.

At Hauptmann's trial two and onehalf years later Betty Gow remembered, and testified, as to the Colonel's exact first words. "Anne," he said, "they have stolen our baby."

At that point the note had not been placed, let alone discovered or read. Its contents were known only to its author. The note referred to a kidnap gang and specifically used the plural "we." However, Lindbergh's use of the plural "they" before he supposedly found the note never raised any police suspicions.

Lindbergh dashed outside with a loaded rifle to look for the kidnappers. Anne and Elsie searched for the child. Oliver Whately eventually went outside to help and was dispatched into town. By the time Lindbergh came back inside Betty, Elsie and Anne had completed their search and had assembled in the downstairs living room.

It was here that Charles Lindbergh reentered the nursery where he remained alone. The room could be hurriedly wiped down with a handkerchief in less than sixty seconds while Anne, Betty and the Whatelys remained downstairs. Until this point no one else had seen a note, despite the search by Anne, Elsie and Betty Gow. It was here, upon emerging from the nursery, that Colonel Lindbergh called to Betty to come upstairs. She did, whereupon the Colonel showed her an envelope on the sill of the southeast window. At Hauptmann's trial she specifically testified that she had not seen that envelope earlier. The Colonel asked her to go to the kitchen to get a knife and she obliged.

Lindbergh needed someone to see that envelope, and recalling Betty upstairs so that he could tell her to go downstairs to get a knife to open the envelope served that purpose. For reasons of logic, it served no other.

With that one act Charles Lindbergh was home free. The child was gone, the time of the kidnap had been established with Anne as an alibi for Charles, the fingerprints were wiped away, and the ransom note verifying this as a kidnap was written and planted.

All that now remained was to play out the role of the victim, to let events take their course come what may. Lindbergh would become the central power of the investigation, tracking its course and ensuring it did not come back to him. An analysis of the subsequent events reveals that he accomplished this fifth and last goal very well indeed.

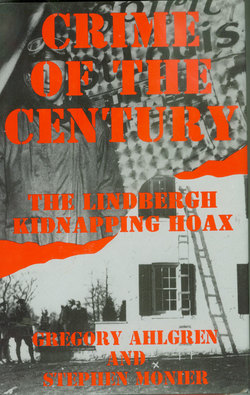

This composite photograph, from the New Jersey State Police archives, displays several items from the "Crime of the Century" (courtesy New Jersey State Police Museum).