Читать книгу Araby - Gretta Mulrooney - Страница 10

ОглавлениеTHREE

I spent a few days with my mother after her return from hospital. She seemed hale and hearty. On the first evening back she headed for the roses with the secateurs, saying that they were getting blowsy. I shopped in Fermoy and bought her a packet of sanitary towels, knowing that she’d be too embarrassed to ask for them herself and wouldn’t mention such an item to my father. She threw them into the kitchen cupboard, saying that I’d had no need to get them ould yokes, wasn’t it all sorted now.

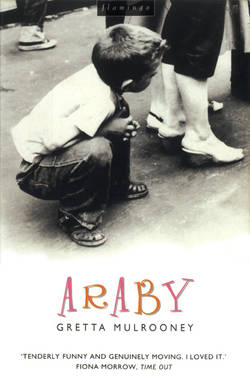

She and my father settled into their routines; feeding and cleaning out the hens, tending the vegetable patch, weeding flowers, collecting juicy nettles for the two rabbits, Collins and Dev. My mother did a good deal of pointing and instructing with her blackthorn stick while my father pulled his old beret down and wielded the hoe. She had started a small herb garden and picked a daily clump of rosemary to put in her pocket. Rolling it through her fingers she sniffed deeply, smiling; it smelled, she said, of Araby.

‘Do you still miss London?’ I asked her as she watered her busy Lizzies. This was a question I would normally avoid, dreading the tale of loss and loneliness that would pour out. But the frightened look in her eyes when Dr O’Kane approached her hospital bed had touched me and I’d felt protective towards her. I suppose I was trying to reassure myself as much as discover her feelings.

She picked off dead leaves, rolling them in her fingers. ‘Some mornings I’d give me right arm to hop on a bus and stop at Rossi’s café for egg and chips.’

‘You could have egg and chips in Fermoy.’

‘It wouldn’t be the same. Yeer father would be worrying at me to get home and there’s no bus.’

‘This is what you always said you wanted when you were in Tottenham; a cottage and half an acre.’ For years she’d complained about the traffic and the noise and the smallness of her garden. I remembered her standing at the back door in the summer, looking out on the patch of drying lawn and saying wistfully that it would be a fine day to be in Kinsale.

‘So I did, so I did.’ Her martyr’s voice took over. ‘Of course I only came here because yeer father was so keen. He had his heart set on it and I couldn’t disappoint him.’

This self-deception left me breathless, even though I’d heard it before. As I recalled, she had been the one to promote the idea; she had bought copies of the Irish papers to look at property. I felt the old familiar guard coming down, the one I’d carefully constructed over the years to protect myself from her manipulations and the webs of illusion that she spun.

‘’Tis terrible lonely here sometimes,’ she said.

‘You could get to know people if you tried; there’s the church.’ I heard my tone; even and dry, distancing myself and warning her to back off. This was a record that we’d played many times before and the lyrics were always the same.

‘Oh, I can’t be doing all that at my age, I’m an old woman.’ On cue, she changed the subject. ‘Do ye ever see the beardy fella?’

‘No.’

‘I wonder is he still there. Do you think would he remember me?’ She looked across the fields, twirling a flower by its stem.

‘I’m sure he would, yes.’ I watched her, knowing that she would carry her discontent wherever she went. I thought of those lines from Much Ado About Nothing; ‘one foot in sea and one on shore’. If she ever reached Heaven there would be a honeymoon period when she would cultivate her preferred saints. Then she would start to find fault with the harps and the constant Glorias, declaring that they were splitting her skull. Saint Peter would be accused of giving her dirty looks.

Back in London I resumed work. At first I phoned each night, then settled back into my usual once weekly call. I was having some tiles replaced on my roof and I watched the workman scale his ladder, thinking that if my mother was here she’d have picked an argument with him before the day was out, alleging that he was hammering too loudly or that he’d scraped the paintwork or knocked over one of her flower-pots. I’d lost count of the number of people she’d fought with, relishing the injection of some drama into her slow-moving days. A plumber who’d come to fix the toilet in Tottenham had been convicted of blasphemy when he’d gestured with his hammer at the picture of the Saviour with the crown of thorns and the moving eyes, asking if it gave us the creeps on dark nights. She had issued many a personal fatwah in her time.

Eight weeks after my return, in the middle of November, I came in one evening and found a message from my father on the answerphone. He shouted slowly, saying that he hoped I would get this but he didn’t understand if he’d waited long enough after the signal. He wondered could I come over. My mother wasn’t well but she wouldn’t let him call the doctor and he was beside himself with worry. Her appetite was gone, he added. He was making this call while she was asleep. She was sleeping a lot, day and night.

I was there the following afternoon. When I walked into the kitchen a sharp blade of shock knifed my chest. She was sitting in the Captain’s chair she’d bought from Snakey Tongue, looking into the distance. She had lost a lot of weight from her face and arms but her stomach was bigger than ever. Her hair was greasy and she was wearing an old apron covered in food stains. Her bare feet looked blueish in faded slippers. When I greeted her she looked up at me and focused but her eyes were lifeless. I’d spent enough time around sick people to know that look; in that moment I realized that she was dying. I bent to kiss her and a rank smell wafted upwards.

‘Have you not been feeling well?’ I drew a chair up.

My father was hovering in the background. ‘Will I just feed the hens and make the tea?’ he asked.

I nodded when my mother didn’t reply. ‘You don’t look too good,’ I said, taking her hand. Her nails were long and dirt-grimed.

‘No, I’m not meself at all. I don’t think I’m well.’ Her voice was low and tired.

‘Why won’t you see the doctor?’

‘Sure he only pokes me about.’

‘Yes, but you really should let him check you.’

She tightened her grip on my hand. ‘Ye won’t put me in a home, will ye?’ she whispered.

I felt a momentary impatience that I quelled. There was no pretend drama now, the question shivered with real fear. ‘Of course I won’t. What makes you think of such a foolish thing?’

‘Yeer father can’t manage. He won’t be able to look after me. Sure he’s full of aches and pains himself.’

‘Listen, you won’t be going into any home. There’s no chance of that. All right?’ I stroked her hand, feeling the veins under the papery skin.

She nodded meekly and her gaze wandered away again, as if she had lost interest.

‘I’m going to ring the doctor,’ I told her. ‘Have you been bleeding at all?’

She shook her head. ‘Just terrible tired. All the grub tastes like ashes.’

My father was throwing grain to the hens. The arthritis in his joints made his movements jerky. He looked as if a strong wind would blow him over.

‘She’s not good,’ he said to me.

‘No. Why didn’t you tell me sooner?’

‘Ah, you know your mother. She has me beat. She wouldn’t go to her hospital appointments, then she put a stop on the doctor. He came one day and she wouldn’t see him, told me to say she was asleep. I was terrible embarrassed with him driving out from Fermoy and all. She’s frightened of going back into hospital. It’s because of Nana.’ His voice was cracked with fatigue.

My grandmother, her mother, had died in hospital after a stroke. I took a handful of the grain and sprinkled it on the ground. A hen strutted and pecked by my feet. My mother loved her hens, just as her mother had. She would stand at the hen-house door, talking to them, calling them her doteys, clucking to them and asking them to lay her beautiful speckledy eggs.

‘I’ve been trying to get her to eat but she won’t. She takes a few mouthfuls. I can’t wash her properly with the old arthritis, I’m frightened I’ll let her fall. I wanted to ring you a couple of weeks ago but she sprang the old tears on me.’ He made a gesture of exasperation and scratched his thin, still sandy hair.

He’d never been able to deal with her if she cried. A blank, terrified look would come on his face and he would slope away to his woodwork or his vegetables.

‘I’ve told her I’m calling the doctor. I’ll do it now.’

He looked relieved. ‘Ah good. She’ll take it from you, she knows you’ve got sense.’

I rang the doctor, a man called Molloy, and caught him just before evening surgery. I’d never met him so I explained who I was.

‘My mother is very ill, I’d like you to visit immediately,’ I said.

He sounded truculent. ‘She’s been very naughty, missing appointments. We haven’t been able to monitor her.’

I bridled at that word, naughty, reducing her to less than adult. What did he know about my mother’s fears? ‘I realize that she has avoided medics but I’m worried about her. She’s lost a lot of weight very suddenly.’

‘No cancer was found in the tests,’ he said quickly and I thought he sounded defensive. He would know that I was a physiotherapist, my mother would be sure to have told him, and I guessed that he was wary of another professional.

‘No, I know that the original tests were clear. Can you come tonight?’

‘Yes, very well. You’ll be there?’

I confirmed that I would. I went into my mother to tell her. My father had given her a cup of tea and she was holding it, untasted, in her lap.

‘I’m mucky, Rory,’ she said. ‘Look at me, I haven’t even had a cat’s lick for a week. What will the doctor think at all?’

I smiled. ‘A cat’s lick’ was the name we’d always given to a quick rub of a flannel on the face.

‘Would you like to have a bit of a clean-up?’ I asked her. ‘I’ll wash your hair for you too. You’ve always liked your hair to look nice.’

I didn’t want Molloy turning his nose up at my mother; I wanted her to have dignity as he probed. I wasn’t sure how she would react to my suggestion. This was the moment when my mother needed a daughter and I wished for a sister to leave delicate tasks to. I was used to manipulating the limbs and kneading muscles of both sexes, but I had never been in the bathroom at the same time as my mother and the barrier of propriety was a strong one.

‘’Tis a fine state I’m in when me son has to help me wash,’ she said but she nodded her agreement.

She let me lead her to the bathroom, walking slowly and giving little groans. Inside she held onto the sink.

‘That was my life-blood draining away when I bled,’ she said flatly.

I smoothed her hair back, paralysed by this sudden insight. She knew the symptoms of cancer; a woman who lived across the road in Tottenham had died of it and my mother had watched her waste away. She had always said the word in a hushed tone, as if to invoke it might bring its wrath on her. I didn’t know what to say. I took the coward’s way out.

‘You’re not well at all, Mum, that’s for sure.’

‘I should have had that operation, years ago.’

‘Maybe. But that’s past now.’

‘Oh everything’s past now.’

There was a silence. My eyes were heavy.

‘Shall we do your hair first?’ I asked gently, pulling up the chair that they threw towels on.

‘I couldn’t be climbing on that,’ she said fearfully in a child’s voice, clutching my arm.

My heart juddered. ‘No, no. No climbing. You can sit on this and rest your head back, like at the hairdresser’s.’

She acquiesced and I helped her lower herself down. I wetted her hair and poured on shampoo, lightly massaging it in. Her temples had become concave and I imagined that if I pressed too firmly my fingers would penetrate her scalp. Strands of hair came out on my knuckles, threading them together. Her hair had been a source of huge pride, thick and wavy into old age. She would often say that it had drawn many compliments in her youth, a honey-coloured delight. For years she had kept it long because she hated hairdressers. They pulled you about, she said, and made an eejit of you. Her scalp was sensitive and the slightest tug on her hair hurt her; she didn’t like anyone touching it. It was still well-coloured with little grey but as I witnessed how thin it had become tears filmed my eyes. This was the first time I had washed my mother’s hair and it was slipping away, swirling into the plughole. Her head seemed weightless in my hands and the brown furry ball webbing my nails emphasized that she was giving up, letting her pride and joy go without a fight. Any hope that I had trickled away with the soapy water. I wanted to weep but I reached for a towel, passing it unobtrusively across my eyes before wrapping it carefully around her head.

‘Now,’ I said, sitting her up as you would a child, ‘was that okay? I didn’t hurt, did I?’

‘No, ye’re very good. The water was lovely.’

‘I was better than those old jades of hairdressers, then?’

She nodded but I didn’t raise a smile. I helped her unbutton her cross-over apron and she stood up so that I could turn the chair around. I soaped a flannel and she ran it around her face and neck and under her arms. The tops of her arms, where there used to be solid quivering fat, were wasted. I turned away and fiddled with the soaps and shaving gear on the shelf behind me, rearranging them. She ran out of energy half way, leaning against the sink rim, so I rinsed the flannel and went back over her skin, wiping away the soap. Her large stomach, slightly exposed beneath the apron, was a yellowy colour. She said that she could manage her other bits herself so I ran fresh water.

‘Shall I help you with your knickers?’ Although she thought of me as a medic, we’d never been in this kind of personal territory before. I hovered, unsure.

‘Just slide them down for me.’

She eased them from the top and I pulled them slowly by their elasticated hems. Then I left her to see if I could find fresh clothes. In the bedroom I searched the chest of drawers and collected clean underwear and a cotton dress. When I got back to her she was resting in the chair, the damp flannel in her hands.

‘All done?’

‘All done,’ she said, ‘mission accomplished.’

Putting her clean knickers on was the hardest part of dressing. It hurt her to raise her legs so I had to carefully lift each foot and manoeuvre the voluminous Aertex garment she liked up her calves and thighs. She moved them upwards, leaning against me, her head pressed to my chest.

‘Do ye remember the time we were on the bus and ye suddenly told me ye’d no underpants on?’ she asked, steadying herself with her arms around my waist.

‘Yes. How old was I?’

‘Oh, four I think. We were after coming out in a hurry. Ye were always difficult about letting me dress ye, ye’d want to do it yeerself. Ye never wanted to hold me hand in the street. Ye called out about the pants in a loud voice. I was mortified.’

In the kitchen I dried her hair, kicking the clumps that fell to the floor under the seat so that she wouldn’t see them.

‘Where’s yeer father?’ she asked, sounding worried.

‘He was with the hens and then he was going to get some turf in.’

‘’Tis getting chilly outside, he doesn’t want to be catching cold.’ She pressed the palms of her hands together. ‘I hate it when the evenings draw in, the place is terrible lonely. Call him in, will ye.’

I went to the door and saw that he was opening the gate for the doctor’s car.

‘Dr Molloy’s here,’ I told her.

‘I can’t go to hospital, I’ve no clean nightdress.’

‘That’s no reason not to go to hospital. If you’re ill, you need to find out what’s the matter and Molloy is only a GP. You need the expertise in hospital.’ I crossed to her. ‘You won’t stay in there, you’ll come home again.’

‘Are ye sure, Rory?’

‘I’ll bring you home myself.’ I kissed her forehead. Now she smelled of peach soap and the talcum she’d asked me to sprinkle over her arms.

Dr Molloy was business-like, which I was grateful for. I was ready to step in if he started taking her to task for misbehaving but when he saw her he just asked her how she was feeling. He spent two minutes examining her, glancing at her stomach, then straightened. He was going to ring for an ambulance, he told her; she must go into hospital that night. She said nothing. My father sat down beside her and said she must try to eat something; how about a bit of an egg custard? The doctor used the phone and I saw him to his car.

‘She’s dying,’ I told him.

He swung his bag onto the passenger seat. ‘It doesn’t look good. Rapid, whatever it is. I can’t say more till the hospital takes a look.’

He accelerated away, his lights fading into the gloom. Once his car had gone there was silence. The faint barking of the ratty dog from up the road floated on the evening air. I bent down to sniff a late rose that my mother had bought on a trip to the garden centre three years ago. I picked a few twigs of rosemary to put in her pocket, hoping that they would make her think of exotic places in the hospital’s antiseptic confines. Turning to the house, I opened the kitchen door. My parents were sitting side by side, hands clasped, looking into the fire.

Nectar

My mother believed in Santa until she was fifteen. When a parlour maid in Youghal laughingly revealed that he was a fiction she cried herself to sleep.

She was born near Bantry, the third of six children. Her father drank and died – I never knew whether from a pickled liver or something else – when she was seven. Her mother struggled to bring her children up on a paltry widow’s pension, doing odd jobs locally and bartering eggs for milk and butter. I’d always had the impression that my mother had been frightened of her father; he was an unpredictable, boisterous man from what she said, although she rarely spoke of him. I suspected that he had been a wife beater. My mother placed great value on the fact that my father was teetotal and of a placid temperament.