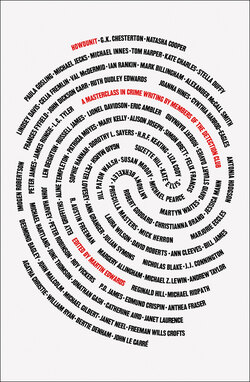

Читать книгу Howdunit - Группа авторов - Страница 20

Putting Murder on the Page Ann Granger

Оглавление‘How do you write a book?’ an earnest woman once asked me. I gave the usual reply: plots, characters, etc. A puzzled frown appeared on her brow. ‘No,’ she said, ‘I meant, how can you put it all together?’ She mimed writing with a pen.

I had been expecting the often-asked ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ But she wasn’t worried about that. I realized she thought of ‘a book’ as a sort of mental Meccano structure. Perhaps, in some ways, it is. But I confess that, at the time, I was stumped as to how to reply in a single sentence.

Writing crime fiction is a slippery subject to pin down. No two writers go about it in the same way. How can we? The books themselves vary so much. One of the attractions of writing mystery/crime has always been, for me, that it is an umbrella covering such a variety of topics, interests, historical periods, and so on.

So, once our thought processes start jogging along, what happens next? Our books are all different. We are all different. We work in different ways.

The only explanation that I can give as to how write a book is to say that it begins by growing in my mind. That does sound rather uncomfortable, if not downright dangerous. But what starts as a germ of a plot with its characters, theme, and so forth does finally threaten to take over and exclude all else. So discipline is very important. Be in charge of the book and don’t let the book become your master.

I must add that writers tend to think a lot before they write anything. Some people might go for long walks, in order to be undisturbed when working out ideas or seeking the right turn of phrase. I’ve been told the poet Wordsworth (though not, of course, a crime writer) used this method, rushing back home to write down the resulting verse before he forgot it again. I’ve had some brilliant ideas in the middle of the night and forgotten them by morning. Or I’ve switched on the light and jotted them down, only to be disappointed when reading the scrawl by the cold light of day. Agatha Christie recommended doing the washing-up as a way of concentrating the mind. Or perhaps the creative activity takes place while staring into space – my own specialty.

There is no guarantee some brilliant idea will come to mind. But, like Mr Micawber, I hope something will turn up.

I have heard of writers who produce a minimum number of words each and every day, come rain or shine. If that is what works for them, excellent. It wouldn’t work for me. I should probably begin each day by binning every word I’d written the previous one.

There are the meticulous planners, whom I admire greatly but couldn’t emulate. There are others who sketch out a plot in general terms, perhaps under headings. Then there are those who know where the starting point is and can see the finishing post in the distance, but don’t know exactly how they are going to get there and so scramble over the obstacles as they go along, in a sort of literary Grand National course.

I start by jotting down a few general notes. I have a location in mind and a set of characters. I work on the principle that if a development in the plot comes as a surprise to me, then, with any luck, it will surprise the reader. I do know the identity of the victim when I begin, and I know the identity of the murderer. If you have created distinctive characters they will helpfully make their own contribution to the mix. ‘Distinctive’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘odd’. A few odd characters are nice, but a complete cast of oddities is confusing. Nor is it enough for a character simply to be eccentric. There has to be some form of reason at work, however bizarre.

It can help to make a few practical notes concerning the colour of a character’s hair or eyes, and also about age. Write down his or her date of birth. Bear in mind, if possible, where your plot is in terms of the working week. Offices and some businesses tend to be closed at the weekend after Saturday lunchtime. If a suspect or a witness is at work, it is no use your detective going to his house during the day.

Setting is important, and I have spotted a few useful locations for scenes of crime while travelling on trains, gazing at the passing countryside. I think to myself, ‘I could put a body there!’

Some years ago I went to the Chelsea Flower Show on a particularly wet day. Everyone there had crowded into the main marquee in a free-for-all. Who, in those circumstances, would be interested in a couple of strangers? Each person there was looking out for him or herself. I thought to myself that a murder could be committed there and no one would notice. The victim, mortally stricken, couldn’t collapse on the ground at once, not in that press. He would slump, allowing the murderer to grasp him and propel him towards the exit, telling everyone who might show surprise that someone had fainted and ‘needed some air’. The surrounding crowd would recognize an emergency and part just enough to allow assailant and victim through.

I went home and wrote a novel called Flowers for His Funeral in which the murder takes place very much in that way.

Make sure you have enough plot. This will probably mean at least one, even two, subplots. But be careful that minor characters don’t become more interesting than the main ones.

I have learned to watch out for a few things over the years. A single page may prove to be a minefield strewn with repetitions and contradictions. Reading aloud is very helpful here. A repeated phrase, for example, may not leap out on the computer screen. But if you have used one, or given the same adjective more than once in a single passage, you will hear it at once if you listen when it’s read aloud.

A section of dialogue can also benefit from being subjected to this test. Speech patterns are important and all the characters should not sound the same.

In my early days I read whole chunks of the day’s output into a tape recorder and played it back. Hearing your voice reciting chunks of your own prose comes as a bit of shock. I remember one of my offspring, on wandering into the room when the tape was running, saying unkindly that I sounded as if I am doing an impression of the Queen’s Christmas speech. I don’t record passages now, but I still read a page or two aloud, when it seems helpful.

When writing my early books, I found myself occasionally in danger of becoming addicted to a particular consonant, especially when thinking of names for characters. Possibly I am alone in that. I know I once wrote a whole chapter in which all the characters, including the corpse, had a name beginning with the same letter. Luckily, I realized in time but it was an alarm bell, and I still watch out for it.

Whether aloud or silently, always read through carefully more than once. Familiarity can be a trap here. You can find yourself skimming over whole pages, the text flashing by in a blur. So it helps to put the finished work aside and go away physically. Go on holiday, tackle the garden; just take yourself away from the work itself. Believe me, it’s much easier to spot the mistakes or glitches after a break away from your creation.

Ronald Knox’s ‘Ten Commandments’ for writing a detective novel date from the 1920s and offer limited assistance for the twenty-first century author. Natasha Cooper draws on experience as an editor and reviewer, as well as from her career as a novelist, in her ten practical tips for crime writers of today.