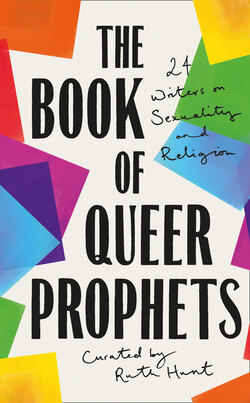

Читать книгу The Book of Queer Prophets - Группа авторов - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

AMROU The Queer Prophet

ОглавлениеI was very excited when asked to contribute to this book, largely because I once actually thought I was a queer prophet. I’m not being ironic. At the height of a nervous breakdown when I was twenty-four, I believed, quite literally, that I must be a prophet.

Some context: growing up in Bahrain, I was taught in the school’s daily Islam lessons to count sins on my left shoulder and good deeds on my right, and to ensure that my left side wasn’t heavier – because if it was, by the time that I died, I’d end up in a cesspit of flames and torture for eternity. Cute, right? Unfortunately, by the age of eight, I had a massive crush on Robin Hood – the cartoon fox – and by eleven, I had formed an attraction to an actual male human – Macaulay Culkin in Home Alone. My homosexuality, as I was taught by instructors (not by the Quran, I should add), would result in an infinite number of sins that would be insurmountable.

The punishments of hell were described to us in intimate detail. While water in heaven was a redemptive, cleansing element, in hell we’d be forced to drink and bathe in boiling water. ‘Close your eyes and imagine the heat on your skin and in your stomach,’ our teacher would tell us. I fully internalised the belief that Allah was a force who would want me to burn for who I was, and this seeped into every part of me. So, by the age of thirteen, I fully renounced Islam and stopped speaking Arabic, because I felt that these cultures would be inhospitable to my queer identity.

Home life with my parents became so traumatic that I looked for ways to leave early. At the age of sixteen I applied for a scholarship to boarding school; by the time I went to university, I was barely in contact with my family. When I started as a student at Cambridge, it was the first time in my life that I was finally, completely, outside any form of parental surveillance, and it gave me the freedom I so yearned for throughout my teenage years.

As if the part that lay dormant inside me was acting on autopilot, I almost immediately organised a student drag night, where I began to form a community of fellow queers that allowed me to find a sense of self. Being in drag was the most powerful I had ever felt. Everything in my life that I had been taught to see as my weaknesses – such as my femininity – suddenly became my strength. I had never felt more like myself – I was totally and utterly hooked. Upon graduating, I decided to try and make it as a drag queen in London, a decision which catalysed a crisis among my Muslim relatives, who said they would denounce me if I continued. According to my mama, I was ‘the source of [her] life’s unhappiness’. As my drag profile grew, so did my family’s resentment, and they turned their backs on me for bringing ‘nothing but shame’ upon them.

While my family tried fervently to suppress my queerness, the London drag scene was its own kind of hyena pit, particularly because it was dominated by white queens; this was accompanied by the endemic racism within the gay community (get on Grindr and it’ll take you around thirty seconds to find a profile that stipulates ‘No Asians’ as a sexual preference). I began to feel as if my queer identity could only operate alongside whiteness, and hence I held the assumption that my being a drag queen was a gift offered to me only by the West (in my early drag career, I only ever dressed as white women from Western pop-cultural contexts). And so I fragmented – my queer identity was severed from my Arab heritage and my racial identity felt erased in the queer spaces I operated in. I was too gay for Arabs and too Arab for gays. I split. The floating parts of my unstable identity could find no singular root, and so I stumbled straight into a nervous breakdown. And one that was alarmingly trippy in character.

The first panicked episode took place on a double-decker bus in London, which I had boarded at 3 p.m. for absolutely no reason. I sat on the top floor by the middle, and there were only a couple of other people on the bus with me. To my left was a young female, headphone-wearing student, sleeping against the window, her jaw half open. A few seats behind me was a large man who I realised was snorting a bit of cocaine on a key – he saw that I saw and gave me a ‘whatever gets you through the day’ look. No judgement here, hun. As the bus started its route I felt a slight tingle around the rim of my face and my head felt very light, as if it might float off at any point. My stomach went fluttery; less like butterfly wings and more like a million locusts flapping their way out. The visual field around me became distorted and eventually, my entire surroundings looked flat, like a 2-D drawing on an extremely thin piece of paper which could rip at any moment. It felt so real that I became panicked that this tear was going to suddenly appear and in an instant there would be no one and nothingness. As my panic intensified, I was eventually thrust back out of the matrix and into the 4-D world I had almost evaporated out of. When I looked around me, I realised that the comatose student and the highly alert businessman were gone and that I was in Penge, the final stop of the London bus I had aimlessly taken.

The frequency of these ‘visions’ grew rapidly, and with little else keeping me tied to reality, I began to take to heart what they were trying to tell me. It was as if my feelings of displacement and not belonging were being actualised. I felt an acute sense of comfort that whatever ‘it’ was that had been guiding me towards these experiences knew that I didn’t belong in this world either. It was as if every instance of not belonging had culminated in this very simple solution – of course I don’t belong in this world. It isn’t real. This rip in the surface of life, whatever it might be, had to be a wormhole to the real, to a site of new dimensions where my belonging could not be called into question. I just had to get to it. I tried closing my eyes during these episodes, hoping that when I opened them I would no longer be me, but a different kind of being in a different kind of place, perhaps even a starfish or an octopus, or something fluid and teeming with multiplicity.

These holes in reality, if I could only find them, seemed to open up the possibility of parallel universes living right under our noses, and I felt a physical pull towards them, as if they were caressing my hair, whispering in my ear a secret I couldn’t quite make out. Maybe this is Allah trying to tell me something? Maybe this is some version of Allah I’d never known about, ushering me towards a path that would provide the solution to all the world’s woes? In a period of my life where I felt so rudderless, this quest to find the rips gave me direction. I began to assume that I must be a prophet who had been gifted with some semblance of a key that would unlock the truth.

Unfortunately, no such key presented itself, and I eventually had to seek medical attention to help me out of my dissociation. The whole episode forced me to acknowledge just how separate my queer identity was from my Muslim heritage, and what the consequences were of having identities so at war with themselves. This intense fragmentation caused me to question the very fact of my being real. And so, to avoid another month of believing I was a prophet – and one with absolutely no clue what their prophecy was – it felt essential that I try to bridge the gap between these disparate parts of myself.

On my re-readings of the Quran, I came across this passage about Allah. It says that Allah is the ‘One who shapes you in the womb as He Pleases’ (Quran 3:6), and that ‘of His signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth and the differences of your tongues and colours’ (Quran 30:22). When I read this, it was the first time in my life that I felt connected to the Quran without having an urge to repel it. I could just hold the book as though it was meant to be in my hands, like a calm, sleeping kitten. There it was, in this ancient ‘evil’ text, the idea that variance and difference among human bodies was all part of Allah’s plan. Perhaps Allah views human beings in the same way I used to think about marine aquatics – as a collection of ever-changing, different bodies, all coexisting as a formless mass unified by light and love. I had only ever pictured Allah as a fascistic punisher who built the world on strict, rigid lines – but the more I discovered about Islam, the less this seemed to be the case.

Rather than being the autocratic religion it has often been painted as, Islam is much freer and open to diversity of interpretation than I realised. This is particularly evident in the case of the ancient Islamic tradition called ijtihad. This essentially refers to the circles of critical thinking and independent discussion that for centuries addressed questions in Islam. Until the tenth century, Muslims were encouraged to exercise autonomy of thinking and to contest the Quran, so that each and every Muslim had their own, independent relationship with the text. The entire point was to allow a multiplicity of experiences and perspectives to inform the practice of Islam. The Quran, in fact, is much more like a collection of poems than a literal series of commandments; its purposeful ambiguity is intended to encourage a diverse range of interpretations. But, as with everything else in the world, cisgender heterosexual men soon dominated the practice, and ijtihad was prohibited in the tenth century, meaning that Islam became more restrictive in the way that people understand it today. Passages like The Story of Lot, which textually seem far more likely to be warnings against rape and inhospitality, could be co-opted by conservative Islamic practitioners into an unequivocal condemnation of homosexuality, leading to the kind of religious institutional homophobia that has scarred my life. It’s not Allah who forbade my queer identity, but the people who ignored the well of alternative potentials in the Quran.

The more I rummaged, the more magic I discovered. Sufism, for instance, is a rich and spiritual sect of Islam that has many affinities with queer identity. As a queer person, I believe almost dogmatically in difference, in the idea that every single person is unique, with their own innate sense of self, and that it is this difference which brings all of us together as one. Sufism, in many ways, is based on a similar belief. It’s a branch of Islam in search of a metaphysical and profound personal dialogue with Allah. In Sufism, every single Muslim has their own individual relationship with Allah; Allah is not a singular hegemonic force that controls us all, but something we can each find individually and on our own terms. While I had grown up to perceive Islam as ascetic and austere, I completely missed an entire genealogy of the faith that directly resonated with me. I had deified the Western literary greats like Oscar Wilde for their queer magic, and completely skipped over the writings of Sufists, like thirteenth-century Persian poet Jalaluddin Rumi, whose dazzlingly spiritual poems are burning with homoerotic desire. It was all there the whole time. Just waiting for me.

Prayer methods in Sufism can be wonderfully poetic, and also intrinsically queer. There is a glorious Sufi sect in which men dress in skirts and spin around and dance as a way to fuse their souls with Allah (the infamous whirling dervishes). YES, THAT’S CORRECT. MALE MUSLIMS WEARING SKIRTS. So while I’d gone about believing that Allah and every relative of mine was prepared to have me burned for my gender identity, there were actually male Muslims wearing dresses and dancing with Allah – and they actually got rewarded for being pious! I mean, I’m basically doing that every time I perform in drag – maybe it’s not so transgressive after all!

When I learned about Sufist whirling dervishes, YouTube (of all places) provided the place where I could more directly see myself. I couldn’t believe the footage I was seeing – men, wearing billowing white skirts that would outdo Kim Kardashian on her wedding day, being celebrated by Muslim people in the audience as they limped their wrists and twirled to the sound of an imam singing the Quran. Here was a version of drag in the most Islamic context; for the first time ever, I actually identified with Muslims on the screen in front of me, each of whom was searching for meaning through costume, music and ritual. Each time I perform, I’m also searching for a transcendental connection with a higher power, channelled through the collective queer energy that comes from the audience. Whenever I get into drag – the quiet ritual of meticulously applying make-up and building a new self – I feel like I did as a young child praying. Islamic prayer is a very charged experience, in which you quietly allow your body to find Allah through movements and mantras. Every time I block out my brows and tell myself in the mirror, ‘you’re fierce’, I feel an affinity with these Islamic practices.

When I am in my full Arabian get-up in front of an audience, I sometimes like to sing in Arabic, acting as a vessel for the beautiful queer feminine energies in Islam, feeling the spiritual power of what it means to be queer and to have a room of many different people celebrating this. It is a kind of religious experience, a room united in the celebration of difference; when a show goes really well, it gives me a kind of faith. A faith that Allah’s plan was for me to twirl onstage in a skirt so that I could eventually find not only myself, but Allah, like many Sufist Muslims had been doing centuries before me.

The most radical thing I discovered in my re-readings of the Quran was about sin. For as long as I remember, I had believed that each sin committed was worth ten points, while each good deed was only worth one, meaning that there were about a trillion times more points on my left shoulder than on my right (somewhat spookily, all chiropractors comment that my left side is much harder to adjust than my right). This, however, was completely wrong. Sins are only worth one point – it is good deeds that are worth ten.

The negative cycles of thought that had come to govern my brain seemed also to have polluted my memories. Islam, particularly, had been reduced to something I only ever thought of as bad. Every neurological pathway that started with Islam always led to feelings of shame and worthlessness and an image of eternal incineration. This clouded the nuance and truth of my religion – and it was these nuances that needed to be rescued, and which ultimately helped me to heal. Allah might not have been a punitive dictator taking relish in my misery. What if Allah was a force that wanted me to do good? What if Allah wanted us to find out that the good was always worth more?

In a way, I kind of think I’m still a prophet. Not in the ‘everyone needs to convert to my way of thinking’ prophet – though hop aboard by all means! – but more that Allah has, in a sense, spoken directly to me. It’s as if Allah threw me into my psychotic breakdown so that I’d be forced to search for an answer to help me escape it. And it was having to return to Allah’s Quran, which is teeming with queerness, that remedied the anguish deep inside me, and which brought my fragmented selves into harmony.

Queer people of faith are ripped apart in all directions. But it is in the delicate art of re-seaming these wounds that transcendence abounds.