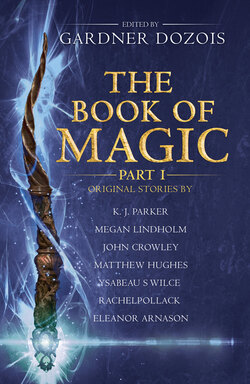

Читать книгу The Book of Magic: Part 1 - Группа авторов - Страница 10

The Return of the Pig

Оглавление[NOSTALGIA; from the Greek, νοστουάλγεα, the pain of returning home]

It was one of those mechanical traps they use for bears and other dangerous pests—flattering, in a way, since I’m not what you’d call physically imposing. It caught me slightly off square, crunching my heel and ankle until the steel teeth met inside me. My mind went white with pain, and for the first time in my life I couldn’t think.

Smart move on his part. When I’ve got my wits about me, I’m afraid of nothing on Earth, with good reason; nothing on Earth can hurt me, because I’m stronger, though you wouldn’t think it to look at me. But pain clouds the mind, interrupts the concentration. When it hurts so much that you can’t think, trying to do anything is like bailing water with a sieve. It all just slips through and runs away, like kneading smoke.

Ah well. We all make enemies. However meek and mild we try to be, sooner or later, we all—excuse the pun—put our foot in it, and then anger and resentment cloud the judgment, and we do things and have things done to us that make no logical sense. An eloquent indictment of the folly of ambition; one supremely learned and clever intellectual does for another by snapping him in a gadget designed to trap bears. You’d take the broad view and laugh, if it didn’t hurt so very, very much.

What is strength? Excuse me if this sounds like an exam question. But seriously, what is it? I would define it as the quality that enables one to do work and exert influence. The stronger you are, the more you can do, the bigger and more intransigent the objects you can influence. My father could lift a three-hundredweight anvil. So, of course, can I, but in a very different way. So: here comes the paradox. I couldn’t follow my father’s trade because I was and still am a weakling. So instead I was sent away to school, where what little muscle I had soon atrophied into fat, and where I became incomparably strong. The hell with anvils. I can lift mountains. There is no mountain so heavy that I can’t lift it. Not bad going, for a man who has to call the porter to take the lids off jars.

The mistake we all make is to confuse strength with security. You think: because I’m so very strong, I need fear nothing. They actually tell you that, in fourth year: once you’ve completed this part of the course you should never be afraid of anything ever again, because nothing will have the power to hurt you. It sounds marvelous, and you write home: dear Mother and Father, this term we’ll be doing absolute strength, so when I see you next I’ll be invincible and invulnerable, just fancy, your loving son, etc. We believe it, because it’s so very plausible. Then you get field assignments and practicals, where you levitate heavy objects and battle with demons and divert the course of rivers and turn back the tides of the sea—heady stuff for a nineteen-year-old—and at the end of it you believe. I’m a graduate of the Studium, armed with strictoense and protected by lorica; I shall fear no evil. And then they pack you off to your first posting, and you start the slow, humiliating business of learning something useful, the hard way.

They mention pain, in passing. Pain, they tell you, is one of the things that can screw up your concentration, so avoid it if you can. You nod sagely and jot it down in your lecture notes: avoid pain. But it never comes up in the exam, so you forget about it.

All my life I’ve tried to avoid pain, with indifferent success.

My head was still spinning when the murderers came along. I call them that for convenience, the way you do. When you know what a man does for a living, you look at him and see the trade, not the human being. You there, blacksmith, shoe my horse; tapster, fetch me a pint of beer. And you see me and you fall on your knees and ask my blessing, in the hope I won’t turn you into a frog.

Actually they were just two typical Mesoge farmhands—thin, spare, and strong, with big hands, frayed cuffs, and good, strong teeth uncorrupted by sugar. One of them had a mattock (where I come from, they call them biscays), the other a lump of rock pulled out of the bank. One good thing about the murderer’s trade—no great outlay on specialist equipment.

They looked at me dispassionately, sizing up the extent to which pain had rendered me harmless. My guess is, they hadn’t been told what I was, my trade, though the scholar’s gown should have put them on notice. They figured I’d be no bother, but they separated anyway, to come at me from two directions. They hadn’t brought a cart, so I imagine their orders were to sling me in a ditch when they were all done. One of them was chewing on something, probably bacon rind.

The thing about strictoense—it’s actually a very simple Form. They could easily teach it in first year, except you wouldn’t trust a sixteen-year-old freshman with it, any more than you’d leave him alone with a jar of brandy and your daughter. All you do is concentrate very hard, imagine what you’d like to happen, and say the little jingle: strictoenseruit in hostem. Personally, I always imagine a man who’s just been kicked by a carthorse, for the simple reason that I saw it happen to my elder brother when I was six. One moment he was going about his business, lifting the offside rear hoof to trim it with his knife. His concentration must have wandered because, quick as a thought, the horse slipped his hold and hit him. I saw him in the split second before he fell, with a sort of semicircular dent a fingernail deep directly above his eyebrows. His eyes were wide open—surprise, nothing more—and then he fell backward and blood started to ooze and his face never moved again. It’s useful when you have a nice, sharp memory to draw on.

If they’d come along a minute earlier, I’d have been in no fit state. But a minute was long enough, and strictoense is such an easy Form, and I’ve done it so often; and that particular memory is so very clear, and always with me, near at hand, like a dagger under your pillow. I tore myself away from the pain just long enough to speculate what those two would look like with hoofprints on their foreheads. Then I heard the smack—actually, it’s duller, like trying to split endgrain, when the axe just sinks in, thud, rather than cleaving, crack—and I left them to it and gave my full attention to the pain, for a very long time.

Two days earlier, we all sat down in austerely beautiful, freezing cold Chapter to discuss the chair of Perfect Logic, vacant since the untimely death of Father Vitruvius. He’d been very much old school—a man genuinely devoted to contemplation, so abstract and theoretical that his body was always an embarrassment, like the poor relation that gets dragged along on family visits. Rumor had it that he wasn’t always quite so detached; he’d had a mistress in the suburbs and fathered two sons, now established in a thriving ropewalk in Choris and doing very well. Most rumors in our tiny world are true, but not, I think, that one.

There were three obvious candidates; the other two were Father Sulpicius and Father Gnatho. To be fair, there was not a hair’s weight between the three of us. We’d known one another since second year (Gnatho and I were a year above Sulpicius; I’ve known Gnatho even longer than that), graduated together, chose the same specialities, were reunited after our first postings, saw one another at table and in the libraries nearly every day for twenty years. As far as ability went, we were different but equal. All three of us were and had always been exceptionally bright and diligent; all three of us could do the job standing on our heads. The chair carries tenure for life, and all three of us were equally ambitious. For the two who didn’t get it, there was no other likely preferment, and for the rest of our lives we’d be subordinate by one degree to the fortunate third, who’d be able to order us about and send us on dangerous assignments and postings to remote and barbarous places, at whim.

I don’t actually hate Sulpicius, or even Gnatho. By one set of perfectly valid criteria, they’re my oldest and closest friends, nearer to me than brothers ever could be. If there’d been a remotely credible compromise candidate, we’d all three have backed him to the hilt. But there wasn’t, not unless we hired in from another House (which the Studium never does, for sheer arrogant pride); one of us it would have to be. You can see the difficulty.

The session lasted nine hours and then we took a vote. I voted for Gnatho. Sulpicius voted for me. Gnatho voted for Sulpicius. In the event, it was a deadlock, nine votes each. Father Prior did the only thing he could: adjourned for thirty days, during which time all three candidates were sent away on field missions, to stop them canvassing. It was the only thing Prior Sighvat could have done; it was also the worst thing he could possibly do. For all our strength, you see, we’re only human.

So there I was, a very strong human with a bear trap biting into my foot.

I’ve always been bad with pain. Before I mastered sicut in terra, even a mild toothache made me scream out loud. It used to make my poor father furiously angry to hear me sniveling and whimpering, as he put it, like a big girl. I was always a disappointment to him, even when I showed him I could turn lead pipe into gold. So the bear trap had me beat, I have to confess. All I had to do was prise it open with qualisartifex and heal the wound with vergens in defectum, fifteen seconds’ work, but I couldn’t, not for a very long time, during which I pissed myself twice, which was disgusting. Actually, that was probably what saved me. Self-disgust concentrates the mind the way fear is supposed to but doesn’t. Also, after something like five hours, judged by the movement of the sun, the pain wore off a little, or I got used to it.

That first stupendous effort—grabbing the wisp of smoke and not letting go—and then fifteen seconds of total dedication, and then, there I was, wondering what the hell all that fuss had been about. I stood up—pins and needles in my other foot made me wince, but I charmed it away without a second’s thought—and considered my shoe, which was irretrievably ruined. So I hardened the sole of my foot with scelussceleris and went barefoot. No big deal.

(Query: why is there no known Form for fixing trivial everyday objects? Answer, I guess: we live such comfortable, over-provided-for lives that nobody’s ever felt the need. Remind me to do something about it, when I have five minutes.)

All this time, of course, it had never once occurred to me to wonder why, or who. Naturally. What need is there of speculation when you already know the answer?

My mother didn’t raise me to be no watch officer; nevertheless, that’s what I’ve become, over the years, for the not-very-good reason that I’m very good at it. A caution to those aspiring to join the Order: think very carefully before showing proficiency for anything; you just don’t know what it’ll lead to. When I was young and newly graduated, my first field assignment was identifying and neutralizing renegades—witchfinding, as we call it and you mustn’t, because it’s not respectful. I thought: if I do this job really well, I’ll acquire kudos and make a name for myself. Indeed. I made a name for myself as someone who could safely be entrusted with a singularly rotten job that nobody wants to do. And I’ve been doing it ever since, the go-to man whenever there’s an untrained natural on the loose.

(Gnatho is every bit as good at it as I am, but he’s smart. He deliberately screwed up, to the point where senior men had to be sent out to rescue him and clear up the mess. It had no long-term effect on his career, and he’s never had to do it since. Sulpicius couldn’t trace an untrained natural if they were in the same bath together, so in his case the problem never arose.)

No witchfinding job is ever pleasant, and this one … I’d spent five hours in exquisite pain on the open moor, and I hadn’t even got there yet.

I tried to make up time by walking faster, but I’m useless at hills, and the Mesoge is crawling with the horrible things, so it was dark as a bag by the time I got to Riens. I knew the way, of course. Riens is six miles from where I grew up.

Nobody who leaves the Mesoge and makes good in the big city ever goes back. You hear rich, successful merchants waxing eloquent at formal dinners about the beauties of the Old Country—the waterfalls of Scheria, the wide-open sky of the Bohec, watching the sun go down on Beloisa Bay—but the Mesoge men sit quiet and hope their flattened vowels don’t give them away. I hadn’t been back for fifteen years. Everywhere else changes in that sort of time span. Not the Mesoge. Still the same crumbling dry-stone walls, dilapidated farmhouses, thistle- and briar-spoiled scrubland pasture, rutted roads, muddy verges, gray skies, thin, scabby livestock, and miserable people. A man is the product of the landscape he was born in, so they say, and I’m horribly aware that this is true. Trying to counteract the aspects of the Mesoge that are part and parcel of my very being has made me what I am, so I’m not ungrateful for my origins; they’ve made me hardworking, clean-living, honest, patient, tolerant, the polar opposite, the substance of which the Mesoge is the shadow. I just don’t like going back there, that’s all.

I remembered Riens as a typical Mesoge town: perched on a hilltop, so you have to struggle a mile uphill with every drop of water you use, which means everybody smells; thick red sandstone town walls, and a town gate that rotted away fifty years ago and which nobody can be bothered to replace; one long street, with the inn and the meetinghouse on opposite sides in the middle. Mesoge men have lived for generations by stealing one another’s sheep. Forty makes you an old man, and what my father mostly did was make arrowheads. Mesoge women are short and stocky, and you never see a pretty face; they’ve all gone east, to work in the entertainment sector. Those that remain are muscular, hardworking, forceful, and short-tempered, like my mother.

The woman at the inn was like that. “Who the hell are you?” she said.

I explained that I was a traveler; I needed a bed for the night, and if at all possible, something to eat and maybe even a pint of beer, if that wouldn’t put anybody out. She scowled at me and told me I could have the loft, for six groschen.

The loft in the Mesoge is where you store hay for the horses. The food is stockfish porridge—we’re a hundred miles from the sea, but we live on dried fish, go figure—with, if you’re unlucky, a mountain of fermented cabbage. The beer—

I peered into it. “Is this stuff safe to drink?”

She gave me a look. “We drink it.”

“I think I’ll pass, thanks.”

There was a mattress in the loft. It can’t have been more than thirty years old. I lay awake listening to the horses below, noisily digesting and stamping their feet. Home, I said to myself. What joy.

The object of my weary expedition was a boy, fifteen years old, the tanner’s third son; it was like looking into a mirror, except he was skinny and at his age I was a little tub of lard. But I saw the same defensive aggression in his sneaky little eyes, fear mixed with guilt, spiced with consciousness of a yet-unfathomed superiority—he knew he was better than everybody else around him, but he wasn’t sure why, or how it worked, or whether it would stunt his growth or make him go blind. That’s the thing; you daren’t ask anybody. No wonder so many of them—of us—go to the bad.

I said I’d see him alone, just the two of us. His father had a stone shed, where they kept the oak bark (rolled up like carpets, tied with string and stacked against the wall).

“Sit down,” I told him. He squatted cross-legged on the floor. “You don’t have to do that,” I said.

He looked at me.

“You don’t have to sit on the cold, wet floor,” I said. “You can do this.” I muttered qualisartifex and produced two milking stools. “Can’t you?”

He stared at me, but not because the trick had impressed him. “Don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said.

“It’s all right,” I said. “You’re not in trouble. It’s not a crime, in itself.” I grinned. “It’s not a crime because it can’t happen. The law takes the view—as we do—that there’s no such thing as magic. If there’s no such thing, it can’t be against the law.” I produced a table, with a teapot and two porcelain bowls. “Do you drink tea?”

“No.”

“Try it; it’s one of life’s few pleasures.”

He scowled at the bowl and made no movement. I poured myself some tea and blew on it to cool it down. “There is no magic,” I told him. “Instead, there are a certain number of limited effects which a wise man, a scholar, can learn to do, if he knows how, and if he’s born with the ability to concentrate very, very hard. They aren’t magic, because they’re not—well, strange or inexplicable or weird. Give you an example. Have you ever watched the smith weld two rods together? Well, then. A man takes two bits of metal and does a trick involving fire and sparks flying about, and the two bits of metal are joined so perfectly you can’t see where one ends and another begins. Or take an even weirder trick. It’s the one where a woman pulls a living human being out from between her legs. Weird? I should say so.”

He shook his head. “Women can’t do magic,” he said. “Everybody knows that.”

A literal mind. Ah well. “Men can’t do it either, because it doesn’t exist. Haven’t you been listening? But a few men have the gift of concentrating very hard and doing certain processes, certain tricks, that achieve things that look weird and strange to people who don’t know about these things. It’s not magic, because we know exactly how it works and what’s going on, just as we know what happens when your dad puts a dead cow’s skin in a big stone trough, and it comes out all hard and smooth on one side.”

He shrugged. “If you say so.”

Hard going. Still, that’s the Mesoge for you. We esteem it a virtue in youth to be unimpressed by anything or anyone, never to cooperate, never to show enthusiasm or interest. “You can do this stuff,” I reminded him. “I know you can, because people have seen you doing it.”

“Can’t prove anything.”

“Don’t need to. I know. I can see into your mind.”

That got to him. He went white as a sheet, and if the door hadn’t been bolted on the outside (a simple precaution), he’d have been up and out of there like an arrow from a bow. “You can’t.”

I smiled at him. “I can see you looking at a flock of sheep, and three days later half of them are dead. I can see you getting a clip round the ear from an old man, who then falls and breaks his leg. I can see a burning hayrick, sorry, no, make that three. Antisocial little devil, aren’t you?”

The tears in his eyes were pure rage, and I softly mumbled lorica. But he didn’t lash out, as I’d have done at his age, as I did during this very interview. He just shook his head and muttered about proof. “I don’t need proof,” I said. “I’ve got a witness. You.” I waited three heartbeats, then said, “And it’s all right. I’m on your side. You’re one of us.”

His scowl said he didn’t believe me. “All right,” I said. “Watch closely. The little fat kid is me.”

And I showed him. Simple little Form, lux dardaniae, very effective. One thing I didn’t do quite right; one of the nasty little escapades I showed him was Gnatho, not me. Same difference, though.

He looked at me with something less than absolute hatred. “You’re from round here.”

I nodded. “Born and bred. You don’t like it here, do you?”

“No.”

“Me neither. That’s why I left. You can too. In ten years, you can be me. Only without the pot belly and the double chin.”

“Me?” he said. “Go to the City?”

And I knew I’d got him. “Watch,” I said, and I showed him Perimadeia: the standard visitor’s tour, the fountains and the palace and Victory Square and the Yarn Market at Goosefair. Then, while he was still reeling, I showed him the Studium—the impressive view, from the harbor, looking up the hill. “Where would you rather live,” I said, “there or here? Your choice. No pressure.”

He looked at me. “If I go there, can my mother and my sisters come and visit me?”

I frowned. “Sorry, no. We don’t allow women, it’s the rules.”

He grinned. “Yes, please,” he said. “I hate women.”

Gnatho was skinny at that age. My first memory of him was a little skinny kid stealing apples from our one good eating-apple tree. They were my apples. I didn’t want to share with an unknown stranger. So I smacked him with what I would later come to know as strictoense.

It didn’t work.

And then there was this huge invisible thing whirling toward me, so big it would’ve blotted out the sun if it hadn’t been invisible, if you see what I mean. I didn’t think; I warded it off, with a Form I would come to call scutumveritatis. I felt the collision; it literally made the ground shake under my feet.

We stared at each other.

I remember quite vividly the first time I looked in a mirror, though of course it wasn’t a mirror, not in the Mesoge; it was a basin full of water, outside on a perfectly still day. I remember the disappointment. That plump, foolish-looking kid was me. And I remember how Gnatho, intently staring at me, lost his seat on the branch of the tree, and fell, and would almost certainly have broken his neck—

I handled it badly. I sort of grabbed at him—adiutoremmeum, used cack-handedly by a ten-year-old, what do you expect?—and slammed him against the trunk of the tree on the way down. The rough bark scraped a big flap of skin off his cheek, and he has the scar still. Stupid fool didn’t think to use scutum, he just panicked; he was so lucky I was there (only if I hadn’t been, he wouldn’t have fallen). But he thought I toppled him out of the tree on purpose and gave him the scar that disfigured him. I showed him my memory when we were eighteen, so he knows the truth. But I think he still blames me, in his heart of hearts, and he’s still scared of me, in case I ever do it again.

There were arrangements. I had to go and see the boy’s parents—long, tedious interview, with the parents scared, angry, shocked, right up until I introduced the subject of compensation for the boy’s unpaid labor. The Order is embarrassingly rich. In the City, ten kreuzers a week will buy you lunch, if you aren’t picky. In the Mesoge it’s a fortune. I’m authorized to offer up to twenty, but it’s not my money, and I’m conscientious.

I walk whenever I can because I have no luck at all with carts and coaches. The horses don’t like me; they’re sensitive animals, and they perceive something about me that isn’t quite right. I cause endless problems to any wheeled vehicle I ride on. If it’s not the horses, it’s a broken axle or a broken spoke, or the coach gets bogged down in a rut, or the driver falls off or has a seizure. I’m not alone; quite a few of us have travel jinxes of one sort or another, and it’s better to be jinxed on land than on sea, like poor Father Incitatus. So, to get to the Mesoge, I take a boat from the City down the Asper as far as Stark and walk the rest of the way. Trouble is, rivers only flow in one direction. To get back from the Mesoge, I have to walk to Insuper, get a lumber barge to the coast, and tack back up to the City on a grain ship. I get seasick and there’s no known Form for that. Ain’t that the way.

From Riens to Insuper is seventeen miles, down dale and up bloody hill. Six miles from Riens, the road goes through a small village; or you can take the old cart road up to the Tor, then wind your way down through the forestry, cross the Blackwater at Sens Ford and rejoin the main road a mile the other side of the village. Going that way adds another five miles or so, and it’s miserable, treacherous going, but it saves you having to pass through this small, typical Mesoge settlement.

Just my luck, though. I dragged all the way up Tor Drove, and slipped and slithered my way down the logging tracks, which were badly overgrown with briars where the logging crews had burned off their brush, only to find that the Blackwater was up with the spring rain, the ford was washed out, and there was no way over. Despair. I actually considered parting the waters or diverting the river. But there are rules about that sort of thing, and a man in the running for the chair of Perfect Logic doesn’t want to go breaking too many rules if there’s any chance of being found out; and since I was known to be in the neighborhood …

So, back I went: up the logging trails and down the Drove, back to where I originally left the road—a journey made even more tedious by reflecting on the monstrously extended metaphor it represented. I reached the village (forgive me if I don’t say its name) bright and early in the morning, having slept under a beech tree and been woken by the snuffling of wild pigs.

I so hoped it had changed, but it hadn’t. The main street takes you right by the blacksmith’s forge—that was all right, because when my father died, my mother sold it and moved back north to her family. Whoever had it now was a busy man; I could hear the chime of hammer on anvil two hundred yards away. My father never started work until three hours after sunup. He said it was being considerate to the neighbors, all of whom he hated and feuded incessantly with. But the hinges on the gate still hadn’t been fixed, and the chimney was still on the verge of falling down, maintained in place by nothing but force of habit—a potent entity in the Mesoge.

I had my hood pinched up round my face, just in case anybody recognized me. Needless to say, everybody I passed stopped what they were doing and stared at me. I knew nearly all of them that were over twenty.

Gnatho’s family were colliers, charcoal-burners. In the Mesoge we’re painfully aware of the subtlest gradations of social status, and colliers (who live outdoors, move from camp to camp in the woods, and deal with outsiders) are so low that even the likes of my lot were in a position to look down on them. But Gnatho’s father inherited a farm. It was tight in to the village, with a paddock fronting onto the road, and there he built sheds to store charcoal, and a house. It hadn’t changed one bit, but from its front door came four men, carrying a door on their shoulders. On the door was something covered in a curtain.

I stopped an old woman, let’s not bother with her name. “Who died?” I asked.

She told me. Gnatho’s father.

Gnatho isn’t Gnatho’s name, of course, any more than mine is mine. When you join the Order, you get a name-in-religion assigned to you. Gnatho’s real name (like mine) is five syllables long and can’t be transcribed into a civilized alphabet. The woman looked at me. “Do I know you?”

I shook my head. “When did that happen?”

“Been sick for some time. Know the family, do you?”

“I met his son once, in the City.”

“Oh, him.” She scowled at me. Lorica doesn’t work on peasant scowls, so I hadn’t bothered with it. “He still alive, then?”

“Last I heard.”

“You sure I don’t know you? You sound familiar.”

“Positive.”

Gnatho’s father. A loud, violent man who beat his wife and daughters; a great drinker, angry because people treated him like dirt when he worked so much harder than they did. Permanently red-faced, from the charcoal fires and the booze, lame in one leg, a tall man, ashamed of his skinny, thieving, no-account son. He’d reached a ripe old age for the Mesoge. The little shriveled woman walking next to the pallbearers had to be his poor, oppressed wife, now a wealthy woman by local standards, and free at last of that pig. She was crying. Some people.

Some impulse led me to dig a gold half-angel out of my pocket and press it into her hand as she walked past me. She looked around and stared, but I’d discreetly made myself hard to see. She gazed at the coin in her hand, then tightened her palm around it like a vise.

I was out of the village and climbing the long hill on the other side a mere twenty minutes later, by my excellent Mezentine mechanical watch. There, I told myself, that wasn’t so bad.

Once you’ve experienced the thing you’ve been dreading the most, you get a bit light-headed for a while, until some new aggravation comes along and reminds you that life isn’t like that. In my case, the new aggravation was another flooded river, the Inso this time, which had washed away the bridge at Machaera and smashed the ferryboat into kindling. The ferryman told me what I already knew; I had to go back three miles to where the road forks, then follow the southern leg down as far as Coniga, pick up the old Military Road, which would take me, eventually, to the coast. There’s a stage at Friest, he said helpfully, so you won’t have to walk very far. Just as well, he added, it’s a bloody long way else.

So help me, I actually considered the stage. But it wouldn’t be fair on the other passengers—innocent country folk who’d never done me any harm. No; for some reason, the Mesoge didn’t want to let me go—playing with its food, a bad habit my mother was always very strict about. One of the reasons we’re so damnably backward is the rotten communications with the outside world. A few heavy rainstorms and you’re screwed; can’t go anywhere, can’t get back to where you came from.

So, reluctantly, I embarked on a walking tour of my past. I have to say, the scholar’s gown is an excellent armor, a woolen version of lorica. Nobody hassles you, nobody wants to talk to you, they give you what you ask for and wait impatiently for you to finish up and leave. I bought a pair of boots in Assistenso, from a cobbler I knew when he was a young man. He looked about a hundred and six now. He recognized me but didn’t say a word. Quite good boots, actually, though I had to qualisartifex them a bit to stop them squeaking all the damn time.

The Temperance & Thrift in Nauns is definitely a cut above the other inns in the Mesoge; God only knows why. The rooms are proper rooms, with actual wooden beds, the food is edible, and (glory of glories) you can get proper black tea there. Nominally it’s a brothel rather than an inn; but if you give the girl a nice smile and six stuivers, she goes away and you can have the room to yourself. I was sleeping peacefully for the first time in ages when some fool banged on the door and woke me up.

Was I the scholar? Yes, I admitted reluctantly, because the gown lying over the back of the chair was in plain sight. You’re needed. They’ve got trouble in—well, I won’t bother you with the name of the village. Lucky to have caught you. Just as well the bridge is out, or you’d have been long gone.

They’d sent a cart for me, the fools. Needless to say, the horse went lame practically the moment I climbed aboard; so back we went to the Temperance for another one, and then the main shaft cracked, and we were ages cutting out a splint and patching it in. Quicker to have walked, I told him.

“I know you,” the carter replied. “You’re from around here.”

There comes a time when you can fight no more. “That’s right.”

“You’re his son. The collier’s boy.”

Most insults I can take in my stride, but some I can’t. “Like hell,” I snapped. I told him my name. “The old smith’s son,” I reminded him. He nodded. He never forgot a face, he told me.

Gnatho’s father, in fact, was the problem. Not resting quietly in the grave is a Mesoge tradition, like Morris dances and wassailing the apple trees. If you die with an unresolved grudge or a bad attitude generally, chances are you’ll be back, either as your own putrifying and swollen corpse or some form of large, unpleasant vermin—a wolf, bear, or pig.

“He’s come back as a pig,” I said. “Bet you.”

The carter grinned. “You knew the old devil, then.”

“Oh, yes.”

Revenant pests don’t look like the natural variety. They’re bigger, always jet-black, with red eyes. They glow slightly in the dark, and ordinary weapons don’t bite on them, ordinary traps can’t hold them, and they seem to thrive on ordinary poisons. Gnatho’s dad had taken to digging into the sides of houses—at night, while the family was asleep—undermining the walls and bringing the roof down. That wouldn’t be hard in most Mesoge houses, which are three parts fallen down from neglect anyway, but I could see where a glowing spectral hog rootling around in the footings wouldn’t help matters.

I know a little bit about revenants, because my grandfather was one. He was a bear, and he spent a busy nine months killing livestock and breaking hedges until a man in a gray gown came down from the City and sorted him out. I watched him do it, and that was when I knew what I wanted to be when I grew up.

Granddad died when I was six. I remember him as a big, cheerful man who always gave me an apple, but he’d killed two of our neighbors—self-defense, but in a small community, that really doesn’t matter very much. The scholar sat up four nights in a row, caught him with a freezing Form (in quo vincit, presumably) and left him there till morning, when he came back with a dozen men, stakes, axes, big hammers—all the kit I tended to associate with mending fences. The only bit of Granddad that could move was his eyes, and he watched everything they did, right up to when they cut off his head. Of course, what I saw wasn’t my dear grandfather, it was a huge black bear. It was only later that they told me.

I don’t know if embarrassment can kill a man. I could have put it to the test, but I got scared and dosed myself with fonslaetitiae, which takes the edge off pretty much everything.

No chance, you see, of anonymity once I got back to the village. Old Mu the Dog—his actual name, insofar as I can transcribe it, is Mutahalliush—was mayor now; my last mental image of him was his face splashed with the stinking dark-brown juice that sweats off rotten lettuce, as he sat in the stocks for fathering a child on the miller’s daughter, but clearly other people had shorter memories or were more forgiving than me. Shup the tanner was constable; Ati from Five Ash was sexton; and the new smith, a man I didn’t know, was almoner and parish remembrancer. I gave them a cold, dazed look and told them to sit down.

I think it was just as bad for them. See it from their point of view. One of their own, a kid they’d smacked round the head with a stick on many occasions, was now a scholar, a wizard, able to kill with a frown or turn the turds on the midden to pure gold. We kept it formal, which was probably just as well.

The meeting told me nothing I didn’t know already or couldn’t guess or hadn’t heard from the carter, but it gave me a chance to do the usual ground-rules speech and impress upon them the perils of not doing exactly as they were told. It was only when we’d been through all that and I stood up to let them know the meeting was over that Shup—my second cousin; we’re all related—asked me if I knew how his nephew had got on. His nephew? And then the penny dropped. He meant Gnatho.

“He’s doing very well,” I told him.

“He’s a scholar? Like you?”

“Very like me,” I said. “He’s never been back, then.”

“We didn’t know if he was alive or dead.”

Or me, come to that. “I’ll tell him about his father,” I said. “He may want to—” I paused, realizing what I’d just been about to say. Pay his respects at the graveside? Which one? A revenant’s remains are chopped into four pieces and buried on the parish boundaries, at the four cardinal points. “He’ll want to know.” And that was a flat lie, but I have to confess I was looking forward to telling him. As he would have been, in my shoes.

Gnatho’s dad wasn’t the sharpest knife in the drawer when he was alive. Dead, he seemed to have acquired some basic low cunning, though that might have been the pig rather than him. It took me three nights to catch him. He didn’t come quietly, and God, was he ever strong. By the time I finally brought him down with posuiadiutorem, I was weak with exhaustion and shaking like a leaf.

Have I misled you with the word pig? Dismiss the mental image of a fat, pink porker snuffling up cabbage leaves in a sty. Wild pigs are big; they weigh half a ton, they’re covered in sleek, wiry hair, and they’re all muscle. Real ones have the redeeming feature of shyness; they sit tight, and if you make enough noise walking around you’ll never ever see one, unless you actually tread on its tail. If you do, it’ll be the last thing you ever do see. The kind, brave noblemen who come out and kill the damn things for us will tell you that a forest pig is the most dangerous animal in Permia, more so than wolves or bears or bull elk. Real pigs are a sort of auburn color, but Gnatho’s dad was soot black, with the unmistakable red eyes.

Once you have your revenant down, you talk to him. I stood up, my legs wobbling under me, and approached as near as I dared, even with a double dose of lorica. “Hello,” I said.

Paralyzed, remember? I was hearing his voice inside my head. “I’m the smith’s boy.”

“That’s right, so you are. You went off to be a wizard in the City.”

“I’m back.”

He wanted to acknowledge me with a nod of the head, but found he couldn’t. “What’s going to happen to me now?”

“I think you know.”

I sensed that he took it resolutely—not happy with the outcome, but realistic enough to accept it. “The pain,” he said. “Will I feel it?”

This is a gray area, but I have no doubts about it myself. “I’m afraid so, yes,” I said. I didn’t add, It’s your fault, for coming back. You don’t score points off someone facing what he was about to go through. “You’ll still be alive, so yes, you’ll feel it.”

“And after,” he said. “Will I be dead?”

I hate having to tell them. “No,” I said. “You can’t die. You just won’t be able to control your body any more. You’ll still be there, but you won’t be able to do anything.”

I felt the wave of sheer terror, and it made me feel sick. To be honest with you, it’s the worst thing I can think of—lying in the dark ground, unable to move, forever. But there you go. It’s not like you decide to be a revenant, and experienced professionals advise you as to the potential downside. It just happens. It’s sheer bad luck. Also, of course, it runs in families, and thanks to a thousand years of inbreeding, the Mesoge is just one big family. I really, really hope it won’t ever happen to me, but there’s absolutely nothing I can do to prevent it.

“You could let me go,” he said. “I’ll move far away, somewhere there’s no people. I won’t hurt anybody ever again. I promise.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “If my Order found out, it’d mean the noose.”

“They’d never know.”

Indeed; how could they? I would go back to the City, swear blind the pig was too strong for me, they’d send someone else, by which time Gnatho’s dad would be long gone (though they always come back; they can’t help it). And I’d lose my reputation as an infallible field agent, which would be marvelous. Everybody wins. And I sometimes can’t help thinking about my granddad, still awake in the wet earth; or what it would feel like, if it’s ever me.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It’s my job.”

We cut him up with a forester’s crosscut saw. If you aren’t familiar with them, they’re the big two-handed jobs. Two men sit on either side of the work; one pushes and one pulls. I took my turn, out of some perverse sense of duty, but I never was any good at keeping the rhythm.

I left my home village with mixed feelings. As I said before, once you’ve been through the experience you’ve been dreading for so long, you feel a certain euphoria; I’ve been back now, I won’t ever have to do it again, there’s a giant weight off my shoulders. But, as I walked up that horribly tiring long hill, I caught myself thinking: no matter how hard I try, this is where I started from, this is part of who I am. I think the revenant issue is what set me thinking that way. You see, revenancy is so very much a Mesoge thing. You get them in other places, but wherever it’s been possible to trace ancestries, the revenant always has Mesoge blood in him, if you go back far enough. God help us, we’re special. Alone of all races and nations, we’re the only human beings on Earth who can achieve a sort of immortality, albeit a singularly nasty one, born of spite and leading to endless pain. Reliable statistics are impossible, of course, but we figure it’s something like one in five thousand. It could be me, one day; or Gnatho, or Quintillus, or Scaevola—learned doctors and professors of the pure, unblemished wisdom, raging in the dark, smashing railings and crushing windpipes. And, as I said, they always—we always—come back, sooner or later. They—we—can’t help it.

Gnatho, a far more upbeat man than I’ll ever be, used to have this idea of finding out how we did it, why it was just us, with a view to conquering death and making all men immortal. I believe he did quite a bit of preliminary research, until the funding ran out and he got a teaching post and started getting more involved in Order politics, which takes up a lot of a man’s time and energy. He’s probably still got his notes somewhere. Like me, he never throws anything away, and his office is a pigsty.

The river had calmed down by the time I got to Machaera, and the military had been out and rigged up a pontoon bridge; nice to see them doing something useful for a change. A relatively short walk and I’d be able to catch a boat and float my way home in relative comfort.

One thing I’d been looking forward to, a small fringe benefit of an otherwise tiresome mission. The road passes through Idens: a small and unremarkable town, but it happened to be the home of an old friend and correspondent of mine, whom I hadn’t seen for years: Genseric the alchemist.

He was in fifth year when I was a freshman, but for some reason we got on well together. About the time I graduated, he left the Studium to take up a minor priorship in Estoleit; after that he drifted from post to post, came into some family money, and more or less retired to a life of independent research and scholarship in his old hometown. He inherited a rather fine manor house with a deer park and a lake. From time to time he wrote to me asking for a copy of some text, or could I check a reference for him; alchemy’s not my thing, but it’s never mattered much. Probably it helped that we were into different disciplines; no need to compete, no risk of one stealing the other’s work. Genseric wasn’t exactly respectable—he’d left the Studium, after all, and there were all sorts of rumors about him, involving women and unlawful offspring—but he was too good a scholar to ignore, and there was never any ill will on his side. From his letters I got the impression that he was proud to have been one of us but glad to be out of the glue-pot, as he called it, and in the real world. Ah well. It takes all sorts.

As with the things you dread that turn out to be not so bad after all, so with the things you really look forward to, which turn out to disappoint. I’d been picturing in my mind the moment of meeting: broad grins on our faces, maybe a manly embrace, and we’d immediately start talking to each other at exactly the same point where we’d broken off the conversation when he left to catch his boat twenty years ago. It wasn’t like that, of course. There was a moment of embarrassed silence as both of us thought, hasn’t he changed, and not in a good way (with the inevitable reflection; if he’s got all middle-aged, have I too?); then an exaggerated broadening of the smile, followed by a stumbling greeting. Think of indentures, or those coins-cut-in-two that lovers give each other on parting. Leave it too long and the sundered halves don’t quite fit together anymore.

But never mind. After half an hour, we were able to talk to each other, albeit somewhat formally and with excessive pains to avoid any possible cause of disagreement. We had the advantage of both being scholars; we could talk shop, so we did, and it was more or less all right after that.

One thing I hadn’t been prepared for was the luxury. Boyhood in the Mesoge, adult life at the Studium, field trips spent in village inns and the guest houses of other orders; I’m just not used to linen sheets, cushions, napkins, glass drinking vessels, rugs, wall hangings, beeswax candles, white bread, porcelain tea-bowls, chairs with backs and arms, servants—particularly not the servants. There was a man who stood there all through dinner, just watching us eat. I think his job was to hover with a brass basin of hot water so we could wash our fingers between courses. I kept wanting to involve him in the conversation, so he wouldn’t feel left out. I have no idea if he was capable of speech. The food was far too rich and spicy for my taste, and there was far too much of it, but I kept eating because I didn’t want to give offense, and the more I ate, the more it kept coming, until eventually the penny dropped. As far as I could tell, this wasn’t Genseric putting on a show. He lived like that all the damn time, thought nothing of it. I didn’t say anything, naturally, but I was shocked.

Over dinner I told him about my recent adventures, and then he showed me his laboratory, of which I could tell he was very proud. I know the basics of alchemy, but Genseric’s research is cutting-edge, and he soon lost me in technical details. The ultimate objective was the same, of course: the search for the reagent or catalyst that can change the fundamental nature of one thing into another. I don’t believe this is actually possible, but I did my best to sound impressed and interested. He had shelves of pots and jars, two broad oak benches covered with glassware, a small furnace that resembled my father’s forge in the way a prince’s baby son resembles a sixteen-stone wrestler. He couldn’t resist showing me a few tricks, including one that filled the room with purple smoke and made me cough till I could barely see. After that, I pleaded weariness after my long journey, and I was shown to this vast bedroom, with enough furniture in it to clutter up the whole of a large City house. The bed was the size of a small barn, with genuine tapestry hangings (the marriage of Wit and Wisdom, in the Mezentine style). I was just about to undress when some woman barged in with a basin of hot water. I don’t think I want to be rich. I’d never get any peace.

I woke up suddenly, feeling like a bull was standing on my chest. I could hardly breathe. It was dark, so I tried lux in tenebris. It didn’t work.

Oh, I thought.

My fault, for not putting up wards before I closed my eyes. There’s an old military proverb; the worst thing a general can ever say is: I never expected that. But here, in the house of my dear old friend— My fault.

I could just about speak. “Who’s there?” I said.

“I’d like you to forgive me.” Genseric’s voice. “I don’t expect you will, but I thought I’d ask, just in case. You always were a fair-minded man.”

The illusion of pressure, I realized, wasn’t so much the presence of some external force as an absence. For the first time in my life, it wasn’t there—it, the talent, the power, the ability. Virtusexercitus, a nasty fifth-level Form, suppresses the talent, puts it to sleep. For the first time, I realized what it felt like being normal. Virtus isn’t used much because it hurts—not the victim, but the person using it. There are other Forms that have roughly the same effect. He’d chosen virtus deliberately, to show how sorry he was.

“This is about the chair of Logic,” I said.

“I’m afraid so. You see, you’re not my only friend at the Studium.”

I needed to play for time. “The bear trap.”

“That was me, yes. Two cousins of my head gardener. It’s a shame you had to kill them, but I understand. I have the contacts, you see, being an outsider.”

You have to concentrate like mad to keep virtus going. It drains you. “You must like Gnatho very much.”

“Actually, it’s just simple intellectual greed.” He sighed. “I needed access to a formula, but it’s restricted. My friend has the necessary clearance. He got me the formula, but it came at a price. Normally I’d have worked around it, tried to figure it out from first principles, but that would take years, and I haven’t got that long. Even with the formula I’ll need at least ten years to complete my work, and you just don’t know how long you’ve got, do you?” Then he laughed. “Sorry,” he said. “Tactless of me, in the circumstances. Look, will you forgive me? It’s not malice, you know. You’re a scholar; you understand. The work must come first, mustn’t it? And you know how important this could be; I just told you about it.”

I hadn’t been listening when he told me. It went straight over my head, like geese flying south for the winter. “You’re saying you had no choice.”

“I tried to get it through proper channels,” he said, “but they refused. They said I couldn’t have it because I wasn’t a proper member of the Studium any more. But that’s not right, is it? I may not live there, but I’m still one of us. Just because you go away, it doesn’t change anything, does it?”

“You could have come back.” They always do, sooner or later.

“Maybe. No, I couldn’t. I’m ashamed to say, I like it too much here. It’s comfortable. There’re no stupid rules or politics, nobody to sneer at me or stab me in the back because they want my chair. I don’t want to go back. I’m through with all that.”

“The boy at Riens,” I said. “Did you—?”

“Yes, that was me. I found him and notified the authorities. I had to get you to come out this way.”

“You did more than that.” I was guessing, but I had nothing to lose. “You found a natural, and you filled his head with spite and hate. I imagine you appeared to him in dreams. Fulgensorigo?”

“Naturally. I knew they’d send you. You’re the best at that sort of thing. If it had just been an unregistered natural, they could have sent anyone. To make sure it was you, I had to turn him nasty. I’m sorry. I’ve caused a lot of trouble for a lot of people.”

“But it’s worth it, in the long run.”

“Yes.”

Pain, you see, is the distraction. As long as I could hurt him, in the conscience, where it really stings, I was still in the game. “It’s not, you know. Your theory is invalid. There’s a flaw. I spotted it when you were telling me about it. It’s so obvious, even I can see it.”

I didn’t need Forms to tell me what he was thinking. “You’re lying.”

“Don’t insult me,” I said. “Not on a point of scholarship. I wouldn’t do that.”

Silence. Then he said, “No, you wouldn’t. All right, then, what is it? Come on, you’ve got to tell me!”

“Why? You’re going to kill me.”

“Not necessarily. Come on, for God’s sake! What did you see?”

And at that precise moment, my fingertips connected with what they’d been blindly groping for: the bottle of aqua fortis I’d slipped into the pocket of my gown earlier, when we were both blinded by the purple smoke. I flipped out the cork with my thumbnail, then thrust the bottle in what I devoutly hoped was the right direction.

Aqua fortis has no pity; it’s incapable of it. They use it to etch steel. People who know about these things say it’s the worst pain a man can suffer.

I’d meant it for Gnatho, of course; purely in self-defense, if he ambushed me and tried to hex me. Pain would be my only weapon in that case. I had no way of getting hold of the stuff at the Studium, where they’re so damn fussy about restricted stores, but I knew my good friend Genseric would have some, and would be slapdash about security.

The pain hit him; he let go of virtus. I came back to life. The first thing I did was lux in tenebris, so I could see exactly what I’d done to him. It wasn’t pretty. I saw the skin bubble on his face, pull apart to reveal the bone underneath; I watched the bone dissolve. You have to believe me when I say that I tried to save him, mundus vergens, but I just couldn’t concentrate with that horrible sight in front of my eyes. Pain paralyzes, and you can’t think straight. It ate deep into his brain, I told him I forgave him, and then he died.

For the record; I think—no, I’m sure—there was a flaw in his theory. It was a false precept, right at the beginning. He was a nice man and a good friend, mostly, but a poor scholar.

As soon as I got back to the Studium, I went to see Father Sulpicius. I told him everything that had happened, including Genseric’s confession.

He looked at me. “Gnatho,” he said.

I shook my head. “No,” I said. “You.”

He frowned. “Don’t be silly,” he said.

“It was you.”

“Ridiculous. Look, I can prove it. I don’t have clearance for restricted alchemical data. But Gnatho does.”

I nodded. “That’s right, he does. So you asked him to get the data for you. He was happy to oblige. After all, he’s your friend.”

“You’re wrong.”

“Genseric had to find the natural. You’re hopeless at that sort of thing; Gnatho’s very good at it. If you’d been able to, you’d have done it yourself. But you had to leave it to Genseric.”

He took a deep breath. “You’re wrong,” he said. “But assuming you were right, what would you intend to do about it?”

I looked at him. “Absolutely nothing,” I said. “No, I tell a lie. I’d withdraw my name for the chair. Just as you’re going to do.”

“And let Gnatho—”

Oh, the scorn in those words. He’d have hit me if he’d been able. He’s always looked down on Gnatho and me, just because we’re from the Mesoge.

“He’s a fine scholar,” I said. “Besides, I never wanted the stupid job anyway.”

The boy from Riens duly turned up and was assigned to a house. He’s settled in remarkably well, far better than I did. Mind you, I didn’t have an influential senior member of Faculty looking out for me, like he has. He could go far, given encouragement. I hope he does, for the honor of the Old Country.

I’m glad I didn’t get the chair. If I had, I wouldn’t have had the time for a new line of research, which I have high hopes for. It concerns the use of strong acids for disposing of the mortal remains of revenants. Fire doesn’t work, we know, because fire leaves ashes; but if you eat the substance away so there’s absolutely nothing left— Well, we’ll see.

He’ll be back, my father used to say, like a pig to its muck. I gather he said it the day I left home. Well. We’ll see about that, too.