Читать книгу Curriculum - Группа авторов - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеArt School is a framework that brings established artists to work with students in both primary and secondary school settings through the organisation of workshops and artist-in-school residencies. I initiated the project in 2014 to explore the interfaces between schools and contemporary art by inviting students and artists to work collaboratively. This book, Curriculum, is a means of encountering Art School obliquely; texts intersect with projects along shoots and tendrils in a topical thicket formed around art and education. The texts contained within do not set out to accomplish the exhausting task of providing documentation and analysis of these projects. Instead, they work outwards to parallel each contributing writer’s interests in these subjects, leaving Art School’s timeline to be traced through a collection of annotated visual material, and the partnerships and affiliations that supported its evolution, detailed in the book’s acknowledgements section. This introduction sets out the foundations on which Art School is based and still operates, particularly in this mode of reflection, and draws attention to the energy that it has generated.

Although its scale is hard to define and its edges are uncertain, I will begin by attempting a quantitative summary. Since its inception, Art School has developed through fifteen projects conducted in Ireland. It has grown through the participation of thirty-three artists, over eight hundred students between the ages of six and eighteen, approximately seventy school teachers and staff, twenty primary and secondary schools, three third-level institutions, three national art centres, four county council arts offices and one national art biennial, and it has gained the support of a variety of regional and national arts and culture institutions in the process. I could go on in terms of videos made, tunnels drilled, strong men produced, gut bacteria cultured, mermaids dredged up and other aspects of the project’s ecology, but I’ll leave those ends loose, to be touched upon later on in this book.

In terms of its form, beyond the residencies and workshops at its core, Art School embraces mutation. It has grown to include exhibitions, publications, presentations, limited-edition posters and even an artist-led chat show. It develops by multiple stakeholders and agents conversing, proposing and negotiating, and is informed by each of its contexts, giving it a porous consistency, ready to mulch in and ferment on location.

Art School’s energy is often provocative. Operating outside the constraints of the formal curriculum and enjoying freedom to experiment, the projects conducted under the aegis of Art School have addressed issues that are topical, pressing and often difficult to discuss. As students encounter artistic production through these subjects, they come to understand that art is much more than aesthetics, and can provide an opportunity to actively reassess a variety of concerns and find new ways of engaging with the world.

The time frames of projects vary considerably, as Art School does not adhere to a single format; workshops and residencies can take place over days in quick succession or extend across months. The day-today logistics of each project are negotiated on a case-by-case basis depending on the time and resources of both Art School and the school that is hosting it. Projects often begin with a site visit, where I have a chance to meet students, teachers, principals and other staff to work through the logistics and ambitions of the project across the table from each other. Following this, I often invite along the artist (or artists) to visit the school, so that they can be introduced to the students with whom they will work, plan their project, consider spaces they are curious to inhabit and enquire about other resources that they might be able to activate.

Given that Art School’s modus operandi is constantly changing, writing proposals has always been an integral aspect of its adaptive architecture as an independent framework. Art School evolves through each proposal, via a new concept that responds to the specific context in which the project is to be set. These have included Other? Other* Other!, which explored otherness in the months following the Marriage Equality Act of 2015,1 and The Masterplan, which investigated the changes occurring in Grangegorman, an area of Dublin undergoing rapid urban renewal.2 Continually working to define the ambition of these projects has kept questions about the potential (perhaps occasionally elusive) role of art in relation to education close at hand.

Art has long had a place in school education, playing an important role in developing the skills, creative expression and imagination of students in the classroom. But the emphasis of art in the classroom setting often remains focused on cultivating a student’s capacity to master established representational techniques and to develop a command over a particular medium. By contrast, Art School draws its inspiration from the active practices of contemporary artists who operate in a variety of media and engage with contemporary social, political and environmental issues such as climate change, urban regeneration, social dilemmas, protest, educational reform, abortion, teenage identity crises, migration, immigration and gender politics.

For example, during her residency at Killinarden Community School, artist Sarah Browne initiated an enquiry into knowledge transferal by showing students a hundred-year-old photograph of students learning to swim on dry land. This led to a discussion about how learning takes place—how it is mediated through mimicry, sensory experience, listening and demonstrating. The students then split into groups, each deciding on something they would like to learn and something to ‘unlearn’ (for example, the students voiced a desire to learn ‘how people come up with ideas’ and to unlearn ‘how to use social media’). These aims were printed in poster format, and formed the beginning lines of a pantoum, which subsequently led to the development of a video work titled How to Swim on Dry Land that was exhibited in Rua Red as part of It’s Very New School in 2017. In support of these sessions, Browne screened video documentation of other artists’ work, including Seven by Mika Rottenberg and Jon Kessler.3 This work involved participants being subjected to intense heat in a sauna-like container and pedalling exercise machines, wearing very little clothing, and producing sweat as the product of this labour. While this video was playing, I remember one of the students turning to me and asking, ‘Are we allowed to be watching this?’ This response made evident what was coming to mind for many of the other students, between scenes of skin, sweat and exertion. Screening this video in the classroom allowed space for thinking through associations between imagery, desire, objectification, competitive self-improvement and capital—an important and evocative knot to untangle in the context of this residency and beyond.

Processes like this might initially appear as unsettling within the context of education, as it is so often understood. Yet, inviting students, teachers and artists to open up and work on such subjects together through Art School has been an overwhelmingly affirmative experience. Perhaps this enthusiasm is a reflection of the challenging times in which we live and our growing sense that conventional modes of learning must adapt and change. Over the years that Art School has been active, it has operated against a backdrop of social, political, economic and environmental change which has manifested in both positive and negative ways in Ireland, as well as on a global scale: social reforms in Ireland, for instance, have extended the rights of women and LGBTQ+ people while, at the same time, a housing crisis has led to a catastrophic rise in homelessness;4 and the climate crisis has sparked a surge of resistance in defence of the interconnected nature of life on our planet, particularly among the young. Contemporary art offers a mode of interrogating these momentous changes, often in ways that are free from the constraints which become embedded within a formal curriculum. The support that Art School has received from arts organisations is also a sign of the growing recognition of the potential of art. There has been an expansion of interest in arts-in-education programming in Ireland, as evidenced by the Arts in Education Charter,5 the National Arts in Education Portal,6 modulating support structures within the Arts Council (Ireland’s major arts funding body),7 and, more recently, Creative Ireland.8 Indeed, the initial stages of Art School were supported by the Wicklow County Arts Office’s fledgling arts-in-education programme, Thinking Visual.9 This interest in the role of art within educational reform extends into popular culture and media as well, with The Sunday Times devoting a full spread to the Art School exhibition It’s Very New School in 2017.10

When introducing the Art School framework to an artist, I emphasise that the goal is to develop workshops and residencies where they can continue their own practice, based on their own research, their own working methodologies and their own beliefs. They do not have to ‘perform’ the role of the artist. Nor should they distil their practice into a format that can be easily evaluated or appraised in order to be legitimised within the school. In fact, the artists whom I have invited to work within Art School are not selected because of previous experience of working in schools. Instead, I approach each artist based on my interest in their current practice and recent exhibitions, sensing that the ways in which they work—or the themes that they explore—will resonate with students within a school setting. For the artist, whose projects and working practice constitute their professional identity, this process of shifting their interests towards the context of the school can be challenging. Nevertheless, the ongoing experience of Art School demonstrates that artists can occupy the space between the independence of their individual practices and the constraints that are embedded in the lived, experienced environment of a school.

The students’ role (and experience) is crucial to the unfolding of each encounter. While they are invited into the unique world of each artist’s practice, students are encouraged to become critically engaged co-producers. This means that artists and students might reciprocally influence each other in ways that have the potential to extend beyond the time they spend together. The nature of this co-production and the relationship between students and artists vary from project to project. Usually an open dynamic has been initiated through a specific moment which served as an icebreaker. I can recall a change in students’ expressions when one of the artists informed them that they were terrible at drawing, and yet that they were artists as well! Or when another artist told the students that they really should go to visit IMMA (the Irish Museum of Modern Art) because, as the people of Ireland, they owned it. I remember a moment when a student’s infant simulator cried out during a performance of John Cage’s 4’33”, its robotic cry followed by muffled laughter as we all tried to focus on the remaining period of ‘silence’.11 Or the look of astonishment and excitement on a group of students’ faces when Maria McKinney described how she made a sculpture to be placed on an Aberdeen-Angus bull using more than 7,000 artificial insemination straws woven together like a corn dolly or a St Brigid’s cross. Every project generated a moment in which the students’ expectations shifted, and in which they realised that there was potential to develop something new, something unknown and not predetermined. The group dynamics during Art School sessions often surprised teachers who sat in to observe them, as quieter students often became actively involved, and different teams of students formed as they negotiated the new activities that they were working to accomplish together. As projects often shifted outside of the classroom—incorporating corridors, gymnasiums, playing fields and other shared spaces—the students’ sense of involvement and ownership grew even stronger, as they experienced what it felt like to perform these actions with the eyes of other students and school staff upon them.

The attitude of the hosting school is also decisive in the formation of each project. As places of learning charged with delivering knowledge and assessing understanding, schools have to be organised. Learning is to be quantified and measured, and there is considerable pressure to achieve year-on-year improvement. Creativity and innovation are sincerely declared as educational values, but they are difficult to instil—let alone to measure. Projects with indeterminate outcomes are therefore both an opportunity and a challenge. The teachers, special needs assistants, principals and school staff do much to set the atmospheres for these projects; they create the time and space for them to happen, and build a mood of anticipation. This is challenging, as there is no simple procedure for schools to open their doors to processes that are not laid down in the neatly tabulated curriculum and the routines of the academic calendar: Art School projects can spill outside the classroom and take root in different parts of the school; they might draw resources in terms of the time and attention of teachers and staff; and they might activate subjects and concepts that are not easily addressed.

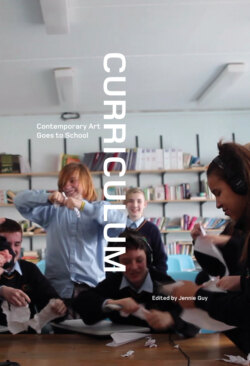

Curriculum—this book—is a means of continuing to evolve the collaborative research and production supported by Art School between 2014 and 2020. In each essay, a different writer approaches a distinct aspect of Art School, whether a specific set of workshops, a single artist’s work or a theme extrapolated from a cluster of projects. Along with these essays, the book includes a collection of annotated visual material which provides a glimpse of different Art School projects as they took place. Most of these images are stills taken from video that I captured while working with the artists in the schools; thus, they provide an active trace of the interaction between artists and students, as well as a sense of the school environments in which these projects took place.12 The images also present several projects that do not feature explicitly in the essays, but that formed part of Art School nonetheless.13 This intertwining of texts, images, projects, works, themes and authors reflects the collaborative working process of Art School itself.

The thirteen texts in Curriculum are as varied as the projects they discuss: some authors have responded in fiction or through dialogue, while others provide vivid contextualisation of the artists and projects. The brief given to the authors was not to document the projects in detail, but to approach them as points set along longer trajectories interweaving art, education and art education. In this way, specific encounters— actual exchanges in Irish schools—are opened up to both global and local considerations: some authors compare Art School projects to initiatives in other places (and other times), while other authors consider how these works resonate in the settings in which they were produced. Moreover, sharing the open-ended spirit of Art School itself, the authors were encouraged to approach the projects as active references rather than as finished products or as case studies that could be analysed and replicated. Considered together, these essays constitute a space of production in themselves—where new questions can emerge and resonate between writers and concepts, and where affinities among the insights gained through Art School can rise to the surface.

The book begins with Nathan O’Donnell’s essay ‘The Outline as Weapon’. O’Donnell directly confronts the unwieldy subject of art in education, discovering a means of contextualising Art School through a consideration of the artist’s outline as a structural (and structuring) device. The essay reveals the outline to be both a fragile bureaucratic artefact as well as a powerful negotiating tool for establishing complicity, depending on how it is used. The text questions the disciplinary prerequisites that are often mistakenly projected onto artists working in educational settings. Through this process, O’Donnell establishes a more nuanced perspective concerning the migration of instincts and resources that accompanies and supports this field of practice.

In ‘We Want to Learn How People Exist’, Rowan Lear delves into her own memories of school, bridging from recollections of the gymnasium (‘I once lost a long swathe of skin to a gym hall floor’) to a work developed by artist Sarah Browne in collaboration with students at Killinarden Community College. Retaining a focus on the architecture of the gym hall, Lear’s contribution considers movement, bodies, collision, injury and collaboration. Lear treats Browne’s video work How to Swim on Dry Land as a lens through which to observe the effects of order and disorder that contemporary art can have in educational settings.

Andrew Hunt’s essay ‘Image of the Self with and Amongst Others’ echoes the title of Mark O’Kelly’s residency with Transition Year students at Our Lady’s School in Terenure, Co. Dublin.14 The text highlights a series of paradoxes that emerge via a communally developed painting produced as this project’s primary outcome. By exploring how the medium of painting is reactivated as it is integrated in social and community processes, Hunt draws attention to preconceptions concerning labour, the artist’s studio and the commodification of art.

Helen Carey’s text examines independent curatorial practice through the trope of ‘the field’, charting a relationship between less certain territories and more established institutions. The essay questions how the independent curator can reveal the kinds of lived knowledge that emerge within this tension, focusing on socially engaged practice and considering how to establish projects that activate both the independent and the institutional sides of this divide. ‘In the Field’ concludes with a brief encounter with It’s Very New School (2017), an exhibition at Rua Red Arts Centre that covered four years of Art School projects.

Hannah Jickling and Helen Reed’s contribution, ‘Weird Science’, oscillates between the authors’ own experiences working in schools in Canada and their engagement with Maria McKinney’s workshop series Birds of Prey, developed with students at St Mary’s National School in Maynooth. The authors characterise schools as a space of ‘joy, subversion, control, kindness, chaos, bullying and friendship’, and thus a productive environment for experimentation and intervention. Jickling and Reed chart McKinney’s curiosity in developing artworks for (and with) animals, passing through considerations of genetics and breeding before linking back to issues of children’s taste as explored in their own work Big Rock Candy Mountain.15

Juan Canela’s contribution considers The Masterplan, a two-stage project featuring John Beattie and Ella de Búrca’s work with primary school students in the Dublin 7 Educate Together National School, and Karl Burke and Naomi Sex’s introduction of Transition Year students from St Paul’s CBS Secondary School to the facilities and teaching in Dublin School of Creative Arts, TU Dublin. Embedded in a neighbourhood that is currently undergoing rapid redevelopment, the project speculates on how (and even if) individuals from different communities might become more aware of each other, looking particularly at the affinities between younger school students and the resources of a nearby university. Canela uses the project as a lens to scrutinise methods that might empower neighbours to explore the strengths that arise through proximity. The essay questions compliance and non-compliance, considering how local residents might have an active voice within the process of urban regeneration.

‘Dear Revolutionary Teacher…’ emerges from a dialogue between curator Sofía Olascoaga and artist Priscila Fernandes. Initiated via Fernandes’ work A friend in common, commissioned for the Art School exhibition It’s Very New School in 2017, the text delves into the history of Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia’s Modern School (Escuela Moderna), a primary school for children and their parents that existed between 1901 and 1909 in Barcelona. Linking back to Fernandes’ ongoing research into this subject, the text invites the reader to reflect on the continued currency of Ferrer’s ideas by reading a series of fictitious letters that the educationalist could have written and received from artists of the day, including Van Gogh and Matisse.

Daniela Cascella’s ‘How Many Elsewheres? (For Four Voices)’ proposes a labyrinthine exploration of sound and listening as a new means of coming to know what it is to be in school. Cascella’s four voices follow auditory traces that transform the potential of the classroom and the relationships that it seeks to contain, drawing inspiration from two series of workshops led by the artist Sven Anderson in Co. Wicklow. The text recalls the spatial deviations, divisions and cuts of Gordon Matta-Clark as it considers a semi-permanent outdoor sound installation developed by Anderson with Transition Year students in Blessington Community College, which prompted the exclamation: ‘WE MADE A HOLE IN THE SCHOOL!’

Matt Packer writes about I Sing the Body Electric, a series of workshops developed in collaboration with curators Clare Breen, Orlaith Treacy and Maeve Mulrennan with students from three West Limerick National Schools as part of the 38th EVA International festival in 2018. This Art School project explored the possibility of integrating workshops focused on curatorial practice (as opposed to artistic practice) within a primary school setting. Packer considers how the project coincided with EVA’s own historical approach to integrating educational initiatives, alongside education and outreach programmes developed by other art institutions and biennales abroad.

Alissa Kleist investigates the potentially subversive role of artists within sites of education, sensing their freedom to move beyond ‘an exchange that ends in a form of closure’ towards one of ‘inconclusive interaction that does not necessarily seek resolution’. Kleist’s text discovers a series of workshops led by artists Hannah Fitz, Jane Fogarty and Kevin Gaffney, with primary school students in Tisrara, Brideswell and Feevagh National Schools in Co. Roscommon. Kleist trains her focus on the prominent role played by animals within Gaffney’s workshops and broader practice, discovering that the artist can literally ‘Play Like Coyote’, as the essay’s title suggests.

Sjoerd Westbroek takes the writers’ brief to its logical conclusion, positioning himself within the experiential framework explored in this book. ‘Exercising Study’ develops through Westbroek’s engagement with a series of cues sent to him by artist Rhona Byrne, developed in an exchange related to Art School workshops led by Byrne with Transition Year secondary students in Blessington Community College in Co. Wicklow and primary school students in Gaelscoil de hÍde and Scoil Mhuire National Schools in Co. Roscommon. Branching off to intersect with workshops led by Elaine Leader with Transition Year secondary students in Blessington Community College, the text weaves these two artists’ works around the experience and conditioning of physical space. The text probes the differences between learning and studying, thoughts that were triggered when accidentally overhearing a fellow train passenger declare ‘I want to study, I do not want to learn’ while rereading Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s book The Undercommons.

By drawing attention to the temporal dynamics of the classroom, Annemarie Ní Churreáin considers both the potential and the responsibility encountered by artists working in schools. ‘Art, the Body and Time Perspective(s) in the Classroom’ advances through Art School residencies and workshops developed by Vanessa Donoso López, Jane Fogarty, John Beattie and Ella de Búrca, considering how these artists approach time in their work with younger audiences. The essay draws from Lopez’s work with primary school students in Gaelscoil de hÍde and Scoil Mhuire National Schools in Co. Roscommon, Fogarty’s anthro-geological project with primary school students in Feevagh and Tisrara National Schools in Co. Roscommon, Beattie and de Búrca’s compositional and performance studies with primary school students in the Dublin 7 Educate Together National School, and a collaborative production by Beattie, de Búrca and myself for the exhibition It’s Very New School (2017) in Rua Red.16 The essay integrates experiences gained through Ní Churreáin’s practice as a poet working in schools, questioning the outsider’s role in researching the mechanics of time as they influence education.

Curriculum draws to a close with Clare Butcher’s ‘Preparatory Gestures for a Future Curriculum’. Butcher’s text contemplates an artist residency in Blessington Community College led by artist Sarah Pierce. Pierce’s workshops evolved through an exploration of Bertolt Brecht’s Lehrstücke, a form of experimental theatre that dissolves the boundaries between actors and audience to explore the revolutionary potential of the medium. Butcher’s text engages with Pierce’s instincts to embed a type of performative pedagogy within the group of students themselves, questioning whether it is possible to measure or evaluate a work of art that is registered in the bodies and the lived experience of those who were both its producers and its primary audience. The work converges on resolutions but not on a final product. Butcher’s rumination on The Square—the central black square at the heart of Pierce’s residency—serves as an apt parallel to the trajectory of Art School itself. Being situated in a mode of continuous rehearsal provides a powerful sense of freedom and agency.

I hope that this book’s title—Curriculum—helps to ensure that it will find its way to a variety of readers who might encounter these essays as a means of seeing how contemporary art can be brought to a school context in order to question the structures through which we choose to teach and to learn. To me, these essays suggest ideas that extend beyond the classroom—and outside of the realm of formal education—and towards different situations in which contemporary art can instigate change. As it builds through these texts, the curriculum that the book encounters (if indeed it does discover such a structure) is transitory, and always in flux. It emerges not from a universal enquiry, but through the specificity of individual practices that converged within real spaces, led by the instincts and interests of students who were only encountering these ways of working and thinking for the first time.

This book owes immense gratitude to all of the students, artists, teachers, principals, school staff and other supporters who contributed to Art School projects as they formed; to the writers and other contributors who have put so much energy into this book; and to the Arts Council of Ireland and the Arts Office of Wicklow County Council for generously funding this book’s production.

1Following a constitutional referendum in Ireland, the legal right for same-sex couples to marry was introduced in November 2015.

2Grangegorman is a new urban quarter being created in Dublin’s north inner city.

3Mika Rottenberg and Jon Kessler presented Seven, a live artwork incorporating seven participants and a video installation, at the Nicole Klagsbrun Project Space in New York as part of Performa 11, 2011.

4The Eighth Amendment to the Irish Constitution, giving an equal right to life to both the unborn and the mother, was repealed following a referendum held on 26 May 2018 allowing abortion services to be made available in Ireland. In terms of the homelessness crisis, it is not unusual for the children who have taken part in Art School projects to be living in temporary emergency accommodation.

5The Arts in Education Charter was launched in 2012 as a collaborative initiative of the Department of Education and Skills (DES) and the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht (DAHG). For more information see education.ie, Publications, Policy Reports, Arts in Education Charter (PDF).

6The Arts in Education Portal was launched in 2014, extending from the Arts in Education Charter and providing an online resource showcasing arts-in-education projects in Ireland. To access the portal, see artsineducation.ie.

7Creative Ireland is an integrated cultural programme launched in 2016, promoting participation in cultural activity on a variety of scales. For more information see creativeireland.gov.ie.

8The Arts Council in partnership with the Department of Education and Skills and the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht launched the Creative Schools initiative in 2019, as a flagship initiative integrated in the Creative Ireland programme. For more information see artscouncil.ie, Arts in Ireland, Young People, Children & Education, Creative Schools.

9The Thinking Visual programme initiated by arts officer Jenny Sherwin supported Art School residencies and workshops at multiple schools in Co. Wicklow between 2014 and 2018. For more information see wicklow.ie, Arts, Heritage & Archives, Arts, Programmes & Initiatives, Thinking Visual.

10Cristín Leach, ‘Lessons for Us All’, The Sunday Times, 19 March 2017.

11An infant simulator is an electric doll that teenagers are given in school to look after for a number of days. This is intended to give a sense of the responsibility of being a parent, though their efficacy in deterring pregnancy has been questioned.

12Many of the videos from which the still images used in this book were extracted can be viewed online at artschool.ie.

13Projects that appear in the visual material but do not feature in the essays include Bead Game (realised in collaboration with Fiona Hallinan) and the permanent artwork Your Seedling Language (by Adam Gibney for St Catherine’s National School in Rush, Co. Dublin).

14Transition Year is a one-year school programme that can be taken in the fourth year of secondary school in Ireland and in which multiple extracurricular subjects and projects are introduced to students. It is optional in most schools and compulsory in others, while in some schools it isn’t feasible, and is skipped.

15Big Rock Candy Mountain is a public artwork by Hannah Jickling and Helen Reed sited in an East Vancouver elementary school, produced by Other Sights for Artists’ Projects.

16This piece for the exhibition It’s Very New School at Rua Red Arts Centre consisted of a sound installation and a floating shelf which held a series of custom-made books. The books’ spines were imprinted with a selection of students’ poetic answers to the questions ‘What is school for?’, ‘What was school for?’ and ‘What will school be for?’, creating an overlap between the universal and the individual, and reminding the spectator that any one question can have a universe of answers.