Читать книгу America - Группа авторов - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE OUTSKIRTS OF THE CITY

By

Marie Darrieussecq

Translated by

Penny Hueston

Iwas born in Bayonne, in the French Basque Country, so for a long time I daydreamed about going to Bayonne, New Jersey. In March 2019, my daughter and I were staying at a friend’s place on the forty-third floor of a tower in Brooklyn; our trip to New York was a present to my daughter for her fifteenth birthday. We were hypnotized by the extraordinary view of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. And every morning, on the other side of the Hudson, a broad, pale smudge lit up beneath the rising sun. Bayonne. I didn’t have binoculars, but I could make out a port area, warehouses, silos, and two very big bridges straddling the water like skeletal dinosaurs.

The geography of New York City is complex. The satellite images show landmasses that seem to have been carved out of the sea with a knife. Bayonne is on a peninsula, Manhattan is an island, and Brooklyn is the western tip of Long Island. There are islands everywhere. In some places, a sandy strip runs along the coast, like on Long Beach or on Fire Island. And, directly opposite, on the other shore of the Atlantic, is the other Bayonne.

One evening, Antoine, a friend of a friend, attended a lecture I gave at New York University, and we discovered that we shared a taste for what are known as “non-places,” places on the periphery. He had been living in New York for twenty years but had never been to Bayonne—why bother? Using the pretext of a promotional flyer he had received that very morning, he thought it would be amusing to attend the grand opening of an enormous supermarket over there. We were to meet at the Hoboken train station, from where we’d head to Bayonne by car. My daughter raised her eyebrows, but the prospect of seeing Manhattan from the other side—and her kindness in indulging her mother’s whims—meant that we set off early and in a good mood.

Hoboken is lucky enough to have the PATH train, which crosses the Hudson in fifteen minutes. The neighboring Jersey City became gentrified through the same public-transport magic and now resembles Brooklyn with its brownstones and its hipster city center. But it takes more than an hour to get from Manhattan to Bayonne. A proposal for a ferry, which would take ten minutes from one side of the river to the other, has been agreed on, and, if all goes to plan, the service could start operating as early as September 2020.

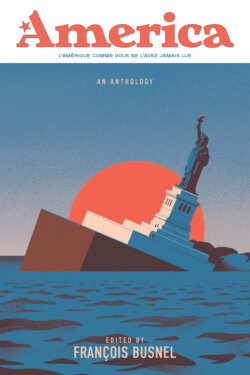

You begin to understand Bayonne when you realize that the Statue of Liberty has its back to the place. You can see only the crown on top of her green copper hair, her face turned toward Manhattan. Bayonne’s small city center is made up of pretty streets, neat rows of modestly proportioned, almost identical wooden houses in pastel shades. All of a sudden there’s a colorful, sixties, Florida-style building that jars with these East Coast surroundings. The public high school, like a huge gothic mansion, is an impressive sight. The public library is housed in a beautiful colonnaded building that dates back to 1904. And then, at the end of the city’s few streets, two colossal bridges sever the space. Light pours forth, the sky is vast, but every walkway is a dead end, cut off by the water. The streets peter out into indeterminate areas, where we drive past gigantic warehouses.

It’s very cold. Wire fencing everywhere. No one around. The chemical factories seem deserted, as if they were operating of their own accord, enormous pipes, pumps, winches, nuts and bolts the size of our heads. At the base of some massive spherical silos, a man in overalls, alone, rails against God. Endless oil tanks lined up ad infinitum. Hummocks of gravel and other materials. A strong sulfurous smell lingers, just as in the much smaller port of my birthplace. We can see only a few workers in fluorescent vests on a military frigate in the dry dock. An abandoned mobile home, covered in brambles, strewn with old domestic items, seems to belong in the opening scene of a David Lynch film. Imagine Twin Peaks without the mountains or the forest, and with the sea instead, broken up by a military-industrial port. It’s as if Bayonne has been breached by a dream fault line that makes strange places accessible.

We pluck up our courage to push open the door of “Starting Point,” which, indeed, turns out to be the departure point for this expedition. We have been wandering around for a little while beneath the vast pylons of a metal bridge that is mind-bogglingly high. From the outside, Starting Point is nothing more than a sign on an off-white, windowless shed. Pole dancing, maybe? A brothel for sailors? We enter a friendly restaurant-bar, open in the middle of the afternoon, where overweight families are eating fried food and old men are watching a football match on the TV.

We gather by the bar. A Budweiser in front of him, Francis Murphy is waiting for his washing to finish its cycle in the laundromat next door. He’s immediately amused by the fact that I was born in Bayonne, France. This anecdote will be my passport everywhere in the city—if in fact I need one, because everybody is extremely welcoming. “Bayonne ham!” Francis exclaims. “Nice and sweet.” He used to be a chef and can’t speak highly enough of the ham from my Bayonne. In the past he found some in Weehawken, not far from here, in a deli that has since closed down. Francis used to work at the Chart House, an upscale restaurant with a view across to Manhattan. The Chart House burned down. Francis launches into a complicated explanation of electrical fires.

I don’t know if Murphy is his real surname, but that’s what he’s called by his buddy, who is as Irish as he is, and who is laden with green scarves he’s selling for St. Patrick’s Day. The two friends have red faces and cube-shaped heads and are downing as many Buds as I am Cokes. Francis is around sixty. He had another buddy here, a native of Tromsø. Tromsø, in Norway, is inside the Arctic Circle. “Well, it turns out that it’s warmer there than in Bayonne, New Jersey. It can get down to minus ten degrees here,” Francis declares, and when I realize he means degrees Fahrenheit, I agree with him: that’s really cold, the equivalent of twenty-three below in degrees Celsius. “It’s because of our geographical position,” he says, “right at the end of the landmass. Because of the sea and the wind. Everything is flat here.”

Bayonne, at the very end of the world, and at the very end of the wind. Francis’s retired buddies have all left the city to go farther south. “You only need to go as few as a hundred miles down this fucking icy coast to find some warmth,” he tells me. Soon, he’s going to move to Atlantic City, the casino town. “I want to gamble myself to death!” Francis used to love Bayonne. But the new bridge has changed everything; Francis’s world has gone, because the rest of the world has arrived, and Francis seems to blame the bridge for exposing the city to people from everywhere else: “The newcomers,” he explains, “haven’t got a clue about the spirit of Bayonne. There are a lot of Spanish, and a real lot of people from the Middle East. Not so many Syrians, no, because of the war, but Egyptians, yes. It’s changed everything.”

“But aren’t you all immigrants here?” I ask.

“We’re all Irish,” he says proudly. “And Italians and Polish as well. And it was the Dutch who founded the city. And, of course, before that, there were the Indians,” he adds, lost in thought now.

We fall silent for a moment. As is often the case when I’m in the United States, I try to imagine the place emptied of concrete and asphalt, populated by nomads and bison.

So it was not the Basque people who founded this city. The name refers only to the idea of a bay, Bay-On. In fact, two large bays and a stretch of water surround it: Newark Bay, New York Bay, and the peculiarly named Kill Van Kull, the strait onto which our little bar, Starting Point, would look out, if it had windows. The demographic details from Wikipedia, which I consult in English so I can present them to Francis, reveal that people of Hispanic origin make up 25 percent of the population, that indeed there are quite a number of Egyptians, and that the city is rather youthful, with an average age of thirty-eight in a total population of 62,000. We also discuss the meaning of the surprising municipal flag, which I have seen flying everywhere alongside the American flag: it looks like a French flag with a boat in the middle, except that the colors could be from Holland in former times. In any case, the famous Bayonne Bridge was for many years the longest steel arch bridge in the world, before it was superseded by four other bridges. It connects New Jersey with Staten Island and, from there, New York.

New York? Francis never goes there anymore. He used to go when he was young, and it was affordable. “I was a hippy.” He had long hair and headed off on his motorcycle to Grateful Dead concerts. Francis is angry as he brings up the long years of redevelopment on the bridge, which have recently made life hell for the city’s inhabitants. “Bayonne was an island,” insists Francis against all the geographical evidence, “but the bridge turned it into a peninsula.”

Perhaps the island he persists in describing to me is a metaphorical one. I am probably underestimating the poetic capabilities of this Trump voter. “It’s a city of fucking Democrats here. I love Trump! Yes, he’s a multimillionaire, but he didn’t take money away from anyone! I blame taxes! Taxes, taxes!” For ten minutes, Francis and I perform a play for which the script is already written. He knows it and he’s enjoying himself; I know it and I’m bored. Fortunately, he’s keeping an eye on his watch, so he can check his laundry. “I hate Clinton,” he says to me out of the blue. “I hate her! We want her executed!” He’s spluttering. “You’re French, you know: I want her guillotined.” And, all at once, I see pure hatred in the eyes of this ordinary man.

Finally, I manage to turn toward the young barman, a very attractive young man with beautiful tattoos. He tells me laconically that he was also born in Bayonne. “Welcome!” He smiles, as if to apologize for Francis, and offers us three Cokes.

So Bayonne, New Jersey, is not famous for anything, apart from the fifth-longest steel arch bridge in the world. And perhaps apart from its monument to the victims of September 11, recommended to us by the young barman. It is very difficult to locate, right at the end of the port area, well beyond Starting Point, and just before the golf course, which is open only in good weather. “Nobody here but me,” says the caretaker of the golf course inside his little heated shed, which looks like a mini Swiss chalet. The clubhouse, on top of an artificial hill, looks like a Bavarian castle crossed with a Breton lighthouse. “Nobody here but me” could be the motto for the whole area, or the motto for us lost travelers.

The monument is a giant drip of nickel suspended inside a tall brick frame, the interior of which looks as if it has been torn away. It’s something of a monstrosity, more than one hundred feet tall, resembling at best a tear, and at worst a saggy scrotum. This Tear Drop Memorial, also known as the Tear of Grief, has been the object of much derision. A plaque informs us that the monument, the work of the Georgian artist Zurab Tsereteli, dedicated “To the Struggle Against World Terrorism,” was a gift to the American people from Vladimir Putin, who traveled here for the unveiling on September 11, 2006, accompanied by Bill Clinton. Part of the tragicomic story behind this monument, which in the end I find moving, is connected to its initial homelessness. A New York Times article from September 16, 2005, recounts how Jersey City declined the offer when approached about the monument. It was supposed to be installed in Exchange Place, the district right opposite Ground Zero on the other side the river, but it was considered “too big” (not to mention too ugly). Several municipalities on the Jersey Shore passed the buck, until the city of Bayonne volunteered to take it. The mayor of Jersey City didn’t hesitate to say, “Be my guest!”

“It’s a weird city,” says the guy at the bar of the Broadway Diner, where we’re sheltering to get warm, a long way from Broadway in New York. “Half of this vast land was won on the water. Those Dutch and their polders. And it’s a city you can never leave. It’s a black hole. I’ve traveled all over the US, and there was someone from Bayonne everywhere I went. It’s like the locals try to get away, but they inevitably come back. You see all those big cargo ships leaving, but you can never leave. I’m stuck here too. I’m a fireman, signed on for five years, but even then, I’m sure I won’t be able to leave.” A huge green neon light above our heads promises “The World’s Best Pancakes.” I ask the guy if he’d like to order anything, but he sticks with his coffee. “Call me Jimmy,” he says, offering me his hand. I’m amazed that everyone here knows the other Bayonne. “It’s because there’s an exchange between the public high schools in the two cities. I went to the Catholic high school here. They’re both good schools, we’re lucky. But people here are weird, weird . . .” Jimmy repeats. “For example, a lot of them believe the water is contaminated with some sort of slow poison or hypnosis drug. And they’re not necessarily wrong: with all the industrial chemicals, what exactly is coming out of the tap? And the rest of New Jersey makes fun of us. There’s that awful joke: ‘When you date someone from Bayonne, leave him or her alone.’ And when I was little, I used to watch a cartoon that was supposed to be funny—this was on national television—and one of the characters would say, ‘Smells like Bayonne!’ Tomorrow is the anniversary of the founding of the city—at the town hall. One hundred and fifty years on March 10. Are you coming?” But tomorrow is actually when I have to go back to France. Jimmy gives a shrug.

The two charming waitresses want to introduce us to a young girl they have gone to find at the back of the room. It turns out she is the German language assistant at the high school. There’s a moment of confusion when we try to explain that German and French are not exactly the same. But the simple fact that we are European elicits enthusiasm. It’s impossible to imagine this scene across the river in New York, or in any city accustomed to tourists. I chat with the waitresses. “You speak the most beautiful language in the world,” one of them says to me over and over. She speaks five languages, but not French or German, even though she has a German passport; she’s Turkish, born in Germany, emigrated here. Her female colleague is Puerto Rican; the cashier is a Chinese woman. Antoine, my daughter, and I eat a lot of pancakes with a lot of maple syrup, and order hot chocolates, which arrive crowned with whipped cream, in half-liter cups. “In France, you eat like birds!” laughs the waitress. Jimmy has to leave. We shake hands effusively. When we go to pay, we discover to our surprise that he has picked up the tab.

We decide to drop by the supermarket that has just opened, a Costco starting up in the same semi-deserted area where the ferry terminal will be built. It is quite simply the biggest supermarket my daughter and I have ever seen. America, the greatest country in the world. Costco sells every conceivable product wholesale: groceries, clothes, toiletries, household appliances. For a start, the mayonnaise comes in three-liter jars, the cereal boxes sell by the dozen, and the shoppers all come in large sizes too. Neither the bodies nor the clothes resemble those in New York. The megamarket is clean, brand-new, the employees are smiling in their red T-shirts. The unemployment rate in Bayonne is 4 percent and rents are much lower than in New York, even if the real-estate pressure is increasing. My daughter is playing with a plush bear that is much bigger than she is; there are a dozen or so in a giant tub.

In the car, we listen to Elysian Fields. In 2000, in another time and in another world, before September 11, 2001, this rock band from Brooklyn wrote dreamy, cool songs for an ethereal voice. One song, called “Bayonne,” seems oceans away from my own birthplace, better known for its bawdy festive songs.

The illuminated skyline of Manhattan rises slowly before us, along the winding roads we take to leave the port. There is nowhere else in the United States where I have felt so intensely the sensation of being “on the edge.” Not exactly at the margins, because the people from Bayonne are neither poor nor disadvantaged, even if it seems they are inclined to be melancholic. But they are from the other side, the opposite shore, not even in the suburbs. They are at the end of the world, although the world is right in front of them. They make me think of the global destiny of all Earthlings: spinning around on a planet situated on the edge of the Milky Way—a luminous spiral that leaves us so far away on the outskirts that we see it as a ribbon—stuck on its shining periphery, far from the center.