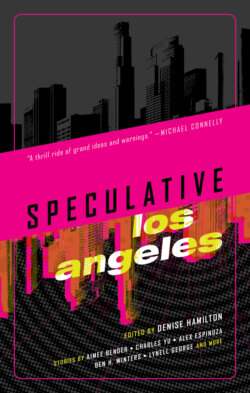

Читать книгу Speculative Los Angeles - Группа авторов - Страница 9

ОглавлениеANTONIA AND THE STRANGER WHO CAME TO RANCHO LOS FELIZ

BY LISA MORTON Los Feliz

At 9:31 a.m. on April 30, 1955, Antonia Feliz discovered a strange man on her land.

She was riding her favorite horse, Balada, along the edge of the river, checking in with her vaqueros and vaqueras, and enjoying the fine spring Alta California morning. The sky overhead was a flawless sapphire, so blue that looking into it was like falling upward into a still sea. The air was scented with sage and lemon blossoms from her orchards, the willows furry with new growth, her cattle grazing contentedly. When she encountered her forewoman, Loo-soo, the dark, muscled Kizh grinned and said, “I think our profits will be very good this year.”

Antonia nodded. “I think they will.” Loo-soo had ridden off then in her electric truck. Antonia preferred horses herself, but the trucks allowed her workers to cover more ground and remove any fallen trees or other large debris.

Loo-soo was right—it would be a good year. Rainfall had been plentiful in the winter, the grazing lands of Rancho Los Feliz were thick and cattle prices were high, and the beehives were already filling up. Her country, Alta California, was at peace with the neighboring United States to the east and Mexico to the south, and her family’s business had prospered under her management. Antonia was thirty-six and had never married, but life had brought her so many other satisfactions that she didn’t miss what she’d never had.

She paused on the hillside, looking down at the river that her Kizh workers called Paayme Paxaayt. She’d heard stories of how it had flooded the Pueblo de Los Ángeles forty years ago, but gazing at its beauty now, at the rippling blue-green expanse crowded with long-necked herons and paddling ducks, it was hard to believe it could ever have been a force of destruction.

As she sat there atop her horse, looking across the river toward Providencia and the low hills beyond, she heard a rustling to her left. A grove of oaks stood there, a stand of mighty survivors several centuries old.

A man staggered out from behind one of the trunks.

He wasn’t like any man Antonia had ever seen: he wore some sort of silvery suit that covered him from foot to neck, with a glass-fronted helmet over his head. At his waist hung a belt studded with instruments—one of which looked like a gun.

Balada neighed and shuffled nervously. “Easy, easy,” Antonia said, patting the horse’s neck.

The man saw her, and although she couldn’t be sure, she thought he tried to talk. He held up his hands, a universal gesture of peace (or surrender), and then reached to latches on either side of the helmet. Undoing the latches, he pulled the helmet free.

Antonia had to restrain a gasp when she saw his face: it was covered in ugly, rippled scars, red and white, and his hair was patchy, burned away. One eye was completely sealed shut; the other fixed on her. “Do you speak English?” he asked, his voice a weathered rasp.

“Who are you? And what are you doing on my land?”

The man looked around. “Your land? I thought … Griffith Park …” He finished the sentence with a groan and then pitched forward.

For a second she was too stunned to move; then she leaped off her mount and ran to where the stranger lay unconscious.

She stood over him for a few seconds, surveying the metallic jumpsuit. Her eyes settled on the belt, on the tool that looked like a gun. She kneeled, used two fingers to gingerly pull it forth from a pocket; she instinctively knew it was a weapon, although she’d never seen its like before.

Running back to Balada, she tucked the gun into a saddlebag, climbed onto her horse, and rode after Loo-soo. She quickly found her tending to a steer that had gotten one leg stuck in a small crevice. Antonia told her forewoman what had happened, and together they returned to the unconscious intruder.

“Chingichnish,” muttered Loo-soo, before asking, “What do we do with him?”

Antonia answered, “He’s a human being, and an injured one. We offer him the same hospitality we would any other visitor.”

Loo-soo used her portable radio to call for help. Two vaqueros rode up, and she directed them to heft the man onto the bed of her truck.

Antonia silently prayed that she hadn’t just made a terrible mistake.

At the hacienda, the vaqueros hauled the man into a ground-floor bedroom while Antonia’s younger brother Abel came over to watch. Antonia telephoned her physician, Dr. Alvarez, and then joined Abel and Loo-soo as they stood over the man.

“What do you think he was doing on our land?” Abel asked.

Antonia felt the subtle assertion of power there—“our land.” Abel always thought he should have been the one placed in charge of Rancho Los Feliz, but he lacked the management skills Antonia had demonstrated since childhood. Abel was handsome, with his gleaming black hair and perfectly trimmed mustache, good at playing the guitar and wooing the pueblo women, but he could barely add two numbers or carry on a civil conversation with an unhappy worker.

Loo-soo asked, “Do you think he’s dangerous?”

“Well,” Antonia said, picking up the saddlebag she’d brought in and opening it to retrieve the gun, “I took this off of him.”

Abel grabbed the weapon, felt its weight, held it up to one eye. “It looks like a gun, but … where is it loaded? I can’t see anywhere for bullets.” After another second, he turned to leave the room. “I’m going to take it outside and try firing it.”

“Abel, no!” Too late; he was gone.

Antonia and Loo-soo exchanged a look as the forewoman struggled to find the words. “Abel is …”

Antonia finished the sentence when Loo-soo couldn’t: “Too often stupid and impulsive.”

Loo-soo continued, “You didn’t answer the question: do you think this man is dangerous? Should we … restrain him?”

“He’s very sick. Even if he wanted to, I don’t think he could do much. I frankly doubt he’ll even survive. Just look at him.” The stranger’s breathing was low but ragged around the edges; he twitched slightly in his unconscious state, Antonia guessed from pain.

“You’re probably right,” Loo-soo agreed.

A huge blast sounded from outside.

Antonia and Loo-soo ran from the house, through the landscaped and tiled courtyard, past the tiered fountain and the intricate wrought-iron gate, to the citrus trees around the front of the house. Abel stood there, staring in wonder at the stranger’s weapon; a hundred feet away, a plate-sized, smoking hole punctuated the trunk of a Valencia orange tree.

Abel looked up from the gun to the tree to his sister. “One shot did that.” He uttered a sharp, shrill laugh that made Antonia’s hair stand on end.

Regardless of what the gun fired or where it had come from, she knew that her brother wasn’t responsible enough to wield that kind of power. Antonia stepped forward, extending a hand. “Give that to me.”

Abel looked like a greedy child as he pulled the gun in toward himself. “No. It’s mine.”

“It’s not—it’s his.” Antonia gestured toward the bedroom where the stranger lay, adding, “What if he wakes up and finds it’s gone? What if he’s got it booby-trapped, or has an even bigger weapon hidden somewhere in that suit?”

Abel couldn’t argue with her logic; he reluctantly placed the gun in her extended hands.

“I’ll hang onto this for now, at least until we know what’s happening with him.”

Abel strode off angrily, leaving Antonia to wonder how long it would be before he tried to steal the gun.

Dr. Alvarez arrived an hour later. Antonia assisted him in removing the unconscious stranger’s silver suit; underneath, he wore a light one-piece stretchy white undergarment, which they also carefully pulled off.

His entire body was covered with scars, some fresh enough to be raw and oozing.

The doctor blanched. “Madre de Dios …” he whispered.

“Have you ever seen anything like this?”

He shook his head. “They look like burn scars, but I can’t imagine what kind of fire would have created those. I’m not even sure how to treat them.” As he rummaged through his travel bag, he asked, “You have no idea where this man came from?”

“None.” Thinking back, Antonia realized there was something else strange about his initial appearance. “He just stepped into view from behind a tree; I don’t understand how I didn’t see him before that.”

Alvarez frowned. “Antonia … for some reason this man makes me think of your father, God rest his soul.”

Antonia knew what the older doctor meant; Alvarez had cared for the Feliz family for forty years, had treated her father after the Invasion of 1943, when the Japanese had landed on the shore just seventeen miles to the west in an attempt to conquer the nation of Alta California before moving on to the United States. Her father had taken a bullet to the chest; he’d been a strong man and had lived another three days—long enough to see the enemy vanquished, their few remaining forces sent home in humiliation—but in the end there’d been no way to save him. Don Alfonso Feliz had died a hero, and had left a will bequeathing control of his beloved business to his then-twenty-four-year-old daughter. Under Antonia, Feliz Agricultural had become one of the most successful companies in Alta California.

“So,” Antonia said to the doctor, as he sat beside his patient, “do you also think this man could be dangerous?”

Alvarez shrugged. “We don’t know anything about him.” He reached into his bag, pulled out a small glass vial. “A sedative. I can give him this; it should ease his pain, and also keep him from regaining consciousness immediately.”

She considered this, and then nodded. “We’ll let him sleep while I make arrangements to hand him over to the authorities.”

Alvarez filled a syringe, injected the man. A few seconds later, his twitching subsided, his breathing became less labored. “Bueno,” the doctor mumbled.

Antonia thanked him, paid him, but knew she’d lied. She had no intention of calling the authorities (what authorities? The local police? Or the national government in Monterey?), at least not right away.

First she wanted a chance to investigate this man’s mysteries on her own.

Thirty minutes later, she stepped down from Balada, threw the horse’s reins around the lowest branch of a cottonwood, and approached the oak grove where she’d first seen her guest.

When she neared the trees her skin began to tingle, as if the air were charged with electricity. She heard a slight buzzing, but couldn’t tell if the sound was real or just in her head. She felt light-headed, a sensation that increased as each step brought her closer to the place where she’d first seen the silver man. Behind her, Balada snorted anxiously, tugging restlessly at the reins.

Antonia reached the tree, more convinced than ever that the man must have been standing there, hidden, for some time before she’d seen him, because she would have noticed any movements.

Then she stepped behind the tree—and froze in shock.

The air—no, everything—behind the tree was torn, split; that was the only way Antonia could describe what she saw. There was her land, the shady grove of oaks to the left, the ground layered in leaves and sprouting weeds, and on her right, cottonwoods and buckwheat that led down to the river … but here, directly in front of her, six feet away, was a rip, a three-foot-wide and six-foot-tall window into some other place. Mesmerized, ignoring both the alarms in her psyche and the increasing nausea in her gut, she stepped forward to peer into the cleft.

She saw an urban nightmare: blocky buildings rose up through ugly vapors, their exteriors cracked and blasted. Nothing grew in that place, not even moss; the only movement was the slight swirl of purplish fog. The sunlight barely penetrated layers of smoke and gas overhead.

It wasn’t only her eyes that were assaulted: she gagged at a smell like burned chemicals and scorched metal. She heard occasional distant blasts.

Once she heard screams. She was thankful she didn’t see what had made those agonized sounds.

That was when she saw something that chilled her entire body: despite the buildings, the obscuring fog, the gloom that resulted from the charcoal-colored clouds overhead, she recognized the land. Here, a slight wrinkle in the topography; over there, the embankment that dropped away, framed in the background by the hills beyond Providencia …

It was her land, her beloved Rancho Los Feliz. “No,” Antonia gasped.

The tingling in her skin gave way to a burning. That was when she staggered back, vomiting into the brush.

When she could stand again, she stumbled over to Balada and rode the horse as hard as she could back to the hacienda. She found Loo-soo and instructed her to assign four workers to guard the oak grove. She asked where Abel was, relieved to hear he’d gone down to the pueblo. She looked in the mirror, and saw, without surprise, that her face had turned as red as if she’d spent the hottest day of the year outside.

Then she called Dr. Alvarez and told him she needed the stranger awake.

She had to tell him to close whatever that hellish door was that he’d opened.

Despite Dr. Alvarez’s efforts to wake him, the man slept for three days. During that time, Antonia saw him begin to recover: the open wounds crusted over, the swelling around the one eye receded, his breathing evened out, the twitching vanished.

Antonia paced. The workers stationed in shifts around the grove had been warned not to enter, and had reported nothing. She herself had ridden out daily to view that awful tear, but it didn’t change. She was only thankful that no one—or nothing—had come through it.

She was at the man’s bedside when he moved, groaned, opened his eyes, and tried to sit up, panicked.

“No, no,” Antonia said, “you are recovering. You’re in my house, where we’ve been caring for you.”

“How long …” His voice, unused too long, grated until he cleared his throat. “How long has it been?”

“Three days.”

He sank back down, accepting the situation. “Thank you.”

Antonia shrugged. “This is how we treat those who fall sick on our land. May I ask your name?”

“Jack Parsons.”

Rising, Antonia said, “I’m happy to meet you, Jack. My name is Antonia Feliz. Would you like something to eat? Maybe some simple broth, until you improve more?”

“Yes, that would be good.”

Antonia rose, went to the kitchen, and returned with a bowl of chicken broth that her chef Manuela had prepared. Jack had managed to sit up in the bed, smiling as she came into the room. “That smells wonderful.”

“Can you feed yourself?”

“I think so.”

As he spooned the broth into his mouth, Antonia studied him. He might once have been an attractive man, although his facial scars made it difficult to know for sure. He didn’t strike her as a soldier; he was middle-aged, of medium height, and there was something inherently smart in the way he studied his environs. She wondered if he’d been a doctor, or a scientist, or if he’d had a family, a wife.

“You must have a lot of questions about me,” he said between spoonfuls.

“Yes, but also about this …” She bent, reached under the bed, removed a wooden box with a small lock, used a key from a pocket in her short jacket to open it, and held up the gun.

Jack stopped eating, his eyes moving from the gun to her face. “Antonia … be very careful with that.”

“My brother fired it, so we know what it can do. Why do you carry it?”

“Purely for defense. I’ve been to some dangerous places.”

As Antonia returned the gun to the box, she half laughed. “Then you don’t come from around here, because the most dangerous place we have is a cantina where my brother drinks too much.”

He took another swallow of soup before asking, “Your name—Feliz—like Los Feliz?”

“This is the Rancho Los Feliz. It has been in my family since 1795.”

“Do you know the names Griffith Park or Los Angeles?”

“I don’t know Griffith Park. But yes, the Pueblo de Los Ángeles is only a few miles to the south.”

Jack finished the bowl and set it down. “What country is this?”

“How could you not know you are in Alta California?”

“Alta California …” Jack smiled and closed his eyes. Within seconds he was asleep.

Antonia was left with nothing but the empty bowl and her questions.

That night, Antonia was awakened by a commotion from outside. She heard raised voices, Loo-soo’s truck approaching, frantic knocking. She grabbed a robe, belted it, and went to the front door. Abel met her halfway, his hair still messy from sleep.

“What is it?”

She answered, “I don’t know,” as she turned on the outside lights and opened the front door.

Loo-soo stood there; behind her, Antonio saw the truck and several vaqueros. “Ramon just got me out of bed. He was on duty outside the oak grove tonight when he heard a strange sound, and then something came out of the trees. He pulled his rifle, but it fell over before he could fire. We think it’s dead.”

“It?”

Loo-soo nodded behind her, her features stony. “Look for yourself.”

Antonia walked to the truck, her chest tightening in dread.

The thing in the back of the truck was small, no more than three feet tall. It was covered in the same thick scars that Jack bore, its rear legs were stubby, the front paws curled into tight claws …

No, not paws—hands. Antonia moved its head slightly toward the light and gasped.

Behind her, Loo-soo asked, “What do you think it is?”

“It’s a child.”

The others around her muttered in surprise. Loo-soo said, “What kind of child looks like that?”

Antonio felt a rush of sympathy for the tiny, scarred thing in the truck. She swallowed it down and turned toward the house and Jack. “That’s what we have to find out.”

Jack awoke the next morning, and this time he was able to eat solid food—a dish of eggs and a common Kizh breakfast. “What is this?” he asked, speaking around the thick porridge. “I’ve never tasted anything quite like it.”

“It’s called we-ch. It’s a local food made from acorns.”

“Weren’t the natives here enslaved by the early Spanish settlers?”

Heat rose to Antonia’s face. “My ancestors did engage in that terrible practice, sí, but that was long ago. Alta California banned slavery in 1843, just seven years after Juan Bautista Alvarado led the revolt that freed us from Mexico. We share the land with the Kizh people now.”

“The ranch bears your name.”

“Yes, but in 1850 we returned Maugna—the original Kizh village here—to them. Those who want to work for me are valued and paid good wages, just as any other worker, and they share in our profits. Why are these things so new to you? You do not come from Alta California, obviously …”

Jack laughed and set his empty plate aside. “Not exactly.” He was searching for words, and Antonia gave him the time he needed. Finally, he looked up at her. “Antonia, you have saved my life and I’m very grateful for your hospitality. That’s all part of why I feel that I owe you the truth, as hard as this might be for you to believe.”

He looked to her for confirmation to continue, and she said, “Jack, I’ve seen that—that place you must have come from.”

“Ahh, of course.”

“I’ve seen your strange clothing, your weapon. And someone else crossed through that portal last night.”

Jack tensed. “Someone else?”

“I think it was a child. It died soon after my vaqueros saw it.”

“Oh.” He took a deep breath. “Antonia, that portal, as you call it, is what we call a TPD—a Temporal Phase Displacement. What you see through it is my world. TPDs allow us to investigate alternate time lines.”

“I’m sorry, I don’t understand.”

“My world was once very much like yours. But at some point, we took divergent paths. I’m guessing technology industries are not very big in your country?”

“No. There is more of that in the United States, but Alta California’s economy is mainly based on agriculture.”

“Imagine a series of clocks lined up in different rooms; each clock is unique, and you can’t see more than one because of the walls, but they all tell exactly the same time. That’s the easiest way I can explain the alternate time lines; they’re all the same place, sitting beside each other but separate, and each developed differently. In my world, we became all about technology. We grew very quickly, and we were poised to expand beyond our world, to move out into the stars, but there was a terrible accident. A group of our scientists lost control of a new form of energy, and it devastated our world. It destroyed the climate, the structures, most of the planet’s life … There are only a few of us left, and we are dying.”

“Like the child …”

“And like me.” Jack looked down, flexed his hands, held the fingers up before his face, and Antonia was shocked to see tears streak down one misshapen cheek. “Although in just the few days I’ve been here, I can feel strength returning.”

Something about Jack’s tone unnerved Antonia; she knew she should have been proud of saving him, bringing him back from death’s edge, but there was a certain calculation in his expression that left her wary. “So your world is as if someone took a right turn instead of a left in the past … ?”

He grinned at her. “Exactly. Is the year here 1955?”

“Yes.”

“And just to the east is the riverbed, yes?”

“Well … yes, but it’s not merely a riverbed. It provides much of our irrigation.”

Jack shook his head in wonder. “And you’re in charge of it all?”

“I took it over after my father died.”

“Are there many women like you? I mean, who are in charge of things?”

Antonia looked at him curiously. “That is a strange thing to ask.”

“Trust me, it’s not that way everywhere. Although I suspect you’d be a remarkable woman in any time line.”

Antonia was surprised to feel heat rush to her face again; Jack saw it and laughed gently; he reached for her hand. Startled, she let him take it.

Jack sighed and gazed out on the bright red bougainvillea and many-armed cacti in multicolored talavera pots that filled the courtyard. He spoke softly, wistfully, as he soaked in the beauty. “My wife is gone, like most of the people in my world. Those of us who were left kept researching and experimenting, and, ironically, we made the most significant discovery in history: that there are infinite time lines, and that we can travel between them.

“The things I’ve seen! I’ve now visited nearly fifty of them. I’ve explored versions of Los Angeles that were uninhabited and wild; I’ve seen others that had been reduced to irradiated desert after a nuclear war. I’ve seen realities where the Japanese annexed this side of the Pacific Rim, from Baja to Canada. I’ve seen one where an attempt to secede from the United States—because yes, in that reality California was part of the US—was quashed and led the state to extreme poverty. I met myself in one reality, but it was a very different me. I’ve seen cities under the sway of religious cults, and I’ve seen cities where a movie business reigns supreme, where a part of Los Angeles is called Hollywood and the world loves their movies. But none of those versions of Los Angeles were as beautiful, as perfect, as this one.”

“We are not so perfect.”

“But you are,” he said. “This whole place looks like a painting. Even your house …”

Antonia glanced around at the stucco walls, the warm colors of linens and draperies. She loved it all, she loved her lands and the people she worked with and her business and her country, but she’d never thought of it as extraordinary in any way.

She also realized she believed him, all of it, as impossible as it seemed. His scars, that dead child, the rift that overlooked a world that held the outlines of her land but was otherwise unrecognizable … what other explanation could there be? “Jack,” she said, drawing his attention back from the courtyard beyond the window, “that … TPD, or whatever you called it … you can close it, yes?”

“Yes. It will close … when I go back.”

“Oh.”

Antonia rose, confused by a rush of emotions. She knew that returning to his world would surely kill him. Did she dare suggest he stay?

She turned to leave the room, but her brother lounged in the doorway so she had to wait for him to step aside. He followed her as she went to the kitchen. “I heard everything,” he said to her, his voice soft but urgent. “Antonia, we have to kill him.”

She turned to face Abel, shocked. “What are you saying?”

“Think: What if he’s lying? What if the sickness from his world is pouring into ours right now, and he knows that? And what if that gateway or whatever it is stays open only as long as he lives? This isn’t just about us, Antonia; this could be our whole world.”

“No, Abel, you’re wrong. We are not getting sick while he is improving. He is not bringing his world to ours, but ours is helping him.”

“We don’t know that.”

“Which is why we are not going to kill a man who may be doing us no harm.”

Abel considered this briefly and then placed a hand on her arm. “At least promise me that you will get him out of here and back to his own world as soon as possible.”

Reluctantly, she agreed.

Abel strode off. As Antonia busied herself making a cup of coffee, she realized her world had changed, thanks to Jack.

The next day, she found Jack walking in his bedroom, slowly but steadily. He’d dressed in the soft white linen shirt and pants she’d laid out for him.

“Antonia … you’ve been very kind—kinder than anyone else I’ve ever known—but I overheard your argument with your brother yesterday, and I think it’s time. Can you take me back to the TPD?”

She nodded, swallowed her disappointment, and left to get a truck. When she returned, she saw that Jack had dressed in the silver suit again. “I’m sorry to ask this, but … my gun?”

Antonia kneeled, pulled out the wooden box, unlocked it, and handed him the weapon. Together, wordlessly, they walked to the truck.

It only took them a few minutes to reach the oak grove. Loo-soo’s vaqueros were still stationed there, but Antonia dismissed them. They seemed relieved to go.

Jack walked forward until he stood before the dark tear, its edges pulsing and shimmering. He removed a device from his belt that looked like a portable radio, and punched buttons on it.

Impulsively, Antonia said, “What if you stay?”

Behind them, someone said, “Oh, that’s sweet.”

Antonia spun to see Abel behind her, a rifle trained on them. “Abel, what … ?”

Her brother’s handsome face turned ugly with fury. “I’m doing what you apparently wouldn’t: making sure this man leaves and doesn’t bring his sickness to our world.”

“Abel, this isn’t necessary—”

“Well, there is one other thing: he’s going to leave that gun before he goes through. I could make good use of that.”

“Good use for what?”

Abel sneered. “Maybe you should just go with him.”

Antonia froze in shock. She opened her mouth to reply, but Jack interrupted: “Antonia, your brother is right—I haven’t been completely honest with you.” His finger hesitated above the device he still held, poised above a red button. “You never asked me why I was here.”

He punched the button.

The world roared. Antonia flinched and clapped her hands to her ears, but there was no way to drown out the terrible sound that nearly forced her to her knees. Behind her, she heard Abel’s rifle go off as he screamed. She looked up and saw that the TPD was widening, expanding, that it was now ten feet … twenty feet … thirty feet wide, one of the oak trees was gone but there were people, not a few as Jack had said but thousands of people in the distance, coming toward them, toward the rift, toward her world.

Antonia understood, then: Jack was a scout. He’d found a new home for the last survivors of his world. They were coming now, bringing their sickness and their science.

“Jack!” she screamed, but then she saw Jack on the ground, dead, the silver suit stained with red where Abel had shot him. Jack couldn’t help her now.

A BOOM told her that Abel had taken Jack’s gun, that he was firing at the wall of people approaching … But even with Jack’s gun, Abel would never be able to hold back this tide.

She wished she’d had some warning; she could have prepared for this. She could have quarantined the refugees until she was sure they weren’t contagious, until she was confident that they wanted only a chance at life, not theft or pillage or conquest. Why hadn’t Jack just asked her? They could’ve worked this out together.

If she’d only had time …

But she knew that time wasn’t hers.