Читать книгу Howl on Trial - Группа авторов - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

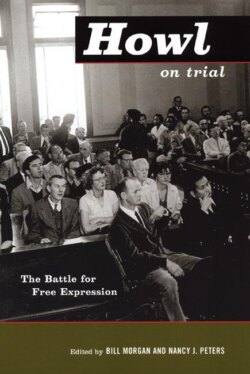

The Struggle for Free Expression

Оглавление1821. Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure by John Cleland, 1749. This is the first-known U.S. obscenity case involving a book, a novel about a the life of a prostitute. Charges were brought in Massachusetts against the book’s U.S. publisher, Peter Holmes, who was convicted for corrupting, debauching, and subverting the morals of youth. It was finally cleared in 1966.

1842. The first federal obscenity law was passed, as the U.S. Tariff Act, which prohibited imports of obscene material from foreign countries and empowered U. S. Customs to seize offending books. This law was largely ignored.

1865. Sending obscene publications through the mail was made a criminal offence; this gave U.S. Postal authorities the power to censor, although they rarely did so.

1873. This is the momentous date when censorship got out of hand. Spearheaded by Anthony Comstock, the first federal anti-obscenity law was passed, a law that prohibited sending through the mail anything that had to do with sex (not just obscenity). State legislatures used it as a model for similar laws; the amalgam of all these laws came to be known as the Comstock Laws.

1881. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman was banned in Boston for sexually explicit language; the expurgation of offending passages was demanded. The poem was later published intact in Philadelphia.

1890. The Kreutzer Sonata by Leo Tolstoi. Forbidden by the U.S. Post Office. Theodore Roosevelt declared Tolstoi to be a “sexual and moral pervert.”

1892. Salome by Oscar Wilde. Banned in Boston.

1915. Hagar Revelly by Daniel Carson Goodman. Warning the young of the dangers of vice, this book was attacked by Comstock because some of the vices were described. The publisher Mitchell Kennerly courageously defended the book and was acquitted. Federal Judge Learned Hand made the first legal challenge here to the Hicklin Rule.

1920. Ulysses by James Joyce. The book was published in installments,beginning in 1918, in Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap’s The Little Review at the Washington Square Bookstore in New York. Copies were seized and burned by U.S. Post Office in 1920. Sylvia Beach published Ulysses in Paris at Shakespeare & Co. in 1922, but Ulysses was forbidden entry into the U.S. Not cleared until 1933.

1922. Mademoiselle de Maupin by Théophile Gautier. Bookstore clerk Raymond D. Halsey was nabbed in 1919 by Sumner’s Society for the Suppression of Vice, tried for selling an obscene book, and acquitted. He then sued the Society for false arrest and malicious prosecution. The New York Court of Appeals read the book, which Gautier had frankly declared in his introduction made light of fornication, adultery, and homosexuality. The court decided in Halsey’s favor. This important case established the precedent that literary experts could offer testimony in support of a book to guide the judge in assessing community opinion.

1927. Elmer Gantry by Sinclair Lewis. Banned in Boston because it depicted an “obscene” clergyman.

1927. The Thousand and One Nights. Seized by U.S. Customs as obscene.

1928. The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall. Cited by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice for pleading tolerance of homosexuality, the book was seized in raids on the publisher’s office and Macy’s book department. The book was cleared in a courtroom victory in 1939.

1929. Candide by Voltaire. This classic was seized by U.S. customs as obscene on its way to a Harvard literature class. (It had been imported without hindrance for the preceding 170 years.) In 1944, the U.S. Post Office demanded that a mail order catalog omit this book. (All the works of Voltaire have been banned at one time or another, many of them burned.)

1929. Confessions by Jean Jacques Rousseau. Banned by U.S. Customs as obscene and injurious to public morality.

1929. Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence. Written in 1928; although acclaimed as a literary masterpiece, the book was banned in England and in the United States for over thirty years.

1930. Amendment of U.S. Tariff Act of 1842 at last allowed a number of classics into the country, including Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, Abelard’s Letters to Heloise, Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders, and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

1930. An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser and The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway banned in Boston.

1933. Ulysses by James Joyce. After Random House’s four-year battle to publish the book, a landmark case (United States v. One Book Called “Ulysses”) was decided by the Federal Court in New York. Judge John. M. Woolsey wrote an eloquent and erudite opinion that esteemed the book as a work of art. He did not apply the Hicklin Rule, and judged the book not by its effects on children but on the average person and held that a work could not be judged on individual passages taken out of context. This effectively ended the Hickin Rule at the federal level.

1934. Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller. Published in Paris in 1934, this book was banned in the U.S. for twenty-seven years. Brought to trial in 1953, the U.S. Customs ban was upheld by the court. Not cleared until 1961.

1946. Action was brought against Kathleen Windsor’s restoration-era bodice ripper Forever Amber. The judge found it “conducive to sleep, but not to sleeping with a member of the opposite sex.”

1946. Memoirs of Hecate County by Edmund Wilson. Banned in several U.S. cities. The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice brought suit against Doubleday, and the New York court found the book obscene. Memoirs of Hecate County then became the subject of the first U.S. Supreme Court obscenity case, heard in 1948. The justices split four to four, Felix Frankfurter abstaining because he knew the author personally. The earlier conviction was then upheld by New York Court of Appeals, which extended the ban through the 1950s.

1948. William Faulkner. Several novels banned in Philadelphia.

1954. Wonder Stories by Hans Christian Anderson stamped “For Adult Readers Only” in Illinois to prevent children from reading smut.

1954. Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio was finally cleared by U.S. Customs.

1957. Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg. This is the earliest application of the Roth standard (Roth v. United States). Book dealer Samuel Roth had been prosecuted in New York for distributing such magazines as American Aphrodite and Photo. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld his conviction, but created an important new standard. Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. concluded that obscenity was not protected by the First Amendment but that literature was. The test of obscenity now became “whether to the average person, applying contemporary standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to the prurient interest.” The Roth case was argued in the U.S. Supreme Court in April 1957, just after Howl was seized, and decided in June, two months before Howl was tried. The Roth decision enabled the ACLU to argue that Howl as a whole had literary merit and did not appeal to prurient interest.

1960. Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D. H. Lawrence. With this book, Barney Rosset at Grove Press began a long, costly campaign to clear outlawed works of significant literature. The importance of the case Grove Press v. Christenberry [the Postmaster General] is that it served as a platform for judges in the District Court and the Court of Appeals to emphasize the importance of artistic merit and the desirability of expressing controversial ideas in a free society.

1961. Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller. Argued by First Amendment lawyers Edward de Grazia and Charles Rembar, the Miller case was finally won, and the book published by Grove Press. The decision was the high benchmark of First Amendment protection of literature: No book should be banned unless it was utterly without social importance. (This led to subsequent arguments that even hard-core pornography could be construed as important.)

1966. Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs. Maurice Girodias published the first edition in Paris in 1959; the book was proscribed in the U.S. In 1962, after Tropic of Cancer was cleared, Grove Press published Naked Lunch. It was challenged and found obscene in Boston in 1965, but the Massachusetts Supreme Court reversed the finding the following year.

1973. Miller v. California. This is the present standard, reflecting the more prohibitive direction the Supreme Court took in the Nixon years. Under the Miller Test, to be obscene, a work’s main theme must be prurient, it must offend contemporary community standards, and it must lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. This last point has been called the “SLAPS test.” Community standards here replaced national standards, and the court attempted to remove hard-core pornography from First Amendment protections.

1978. F.C.C. v. Pacifica Foundation. The Court held that the F.C.C. could create time, place, and matter restrictions on literary and other material to be broadcast. For example, Ginsberg’s “Howl” was among the works restricted to the early morning hours when children would presumably be asleep.

1997. Reno v.ACLU. The Supreme Court struck down the 1996 Communications Decency Act, ruling that it was an unconstitutional attempt to control communications on the Internet. The decision found that the law was too vague in defining obscenity.

1998. National Endowment for the Arts et al. v. Finley et al. The Supreme Court upheld a “decency” standard for NEA grants.

1999–. ACLU v. Ashcroft. Since the 2002 COPA [Child Online Pornography Act] victory of the ACLU in the Supreme Court, cases that concern the government’s attempt to restrict access to “obscene” material on the Internet are still being contested. The ACLU is representing plaintiffs who publish literary and educational materials online, including Salon.com magazine, Powell’s Bookstore, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti/City Lights Books. The language of some of the laws’ propositions could prevent access by everyone (not just children) to educational material on AIDS, for example, or to works of literature. The plaintiffs further assert that reliance on “community standards” improperly allows the most conservative communities to dictate what should be considered indecent. Under present law, Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” could be subject to censorship once again if offered on City Lights’ web site.