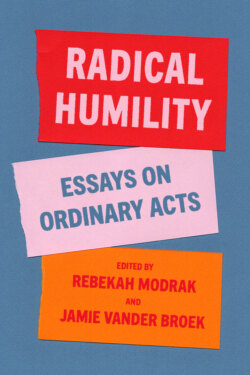

Читать книгу Radical Humility - Группа авторов - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

AN INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеSarah Buss

This collection began with the summer residency featured in the first essay. In July 2016 Rebekah Modrak left behind a world permeated with the value of self-promotion, to live among people whose habits of mind and deed directed their attention—and the attention of others—away from themselves. There, in Aurora, Nebraska, she observed humility as a way of life.

What, exactly, did she observe? The essays that follow are a response to Modrak’s decision to invite people from a wide range of backgrounds to reflect on the nature and value of humility. Perhaps more importantly, most of these reflections describe specific contexts in which humility has played a key role. These contexts include hospitals, universities, and libraries; restaurants and restaurant kitchens; makers’ spaces and the spaces where athletes compete. They include friendships and the relationships between the frail and the healthy.

The variety of styles and the many different perspectives represented in these essays provide us with an antidote to any temptation we may have to make easy generalizations about the issues they address. Nonetheless, several themes emerge. In this introduction, I will call attention to a few of these themes, hoping that the readers will treat my brief observations as a prompt to draw their own connections and raise their own questions.

Humility is commonly contrasted with arrogance and pride. Arrogance is clearly a vice: the vice of assuming that one is superior to, and more important than, others. But what about pride? We encourage our children to be proud of themselves; defenders of equal rights often march under the banner of “pride.” In short, as several of the essays suggest, though a person cannot be both arrogant and humble, there is an important sense in which someone can be proud and humble at the same time.

This point is closely related to another: humility is not servility. To refrain from regarding oneself as superior to others is not to regard oneself as inferior. As Aaron Ahuvia and Jeremy Wood note, hierarchical societies value this deferential stance—at least in those who are at a lower level in the hierarchy. But we no longer see things this way. We do not think that this sort of deference is compatible with self-respect. It is widely assumed that if we value ourselves properly, we will interact with one another as equals.

This having been said, it would be a mistake to conclude that the disposition to defer to others is no longer one of the things we value in valuing humility. As several of the essays in this collection stress, to be humble is to appreciate one’s fallibility. It is to know how little one knows. Indeed, as Troy Jollimore and Charles M. Blow remind us, humility involves acknowledging that some people are one’s superiors in knowledge, given their experience and training. And it involves being disposed to learn what one can from these people. To be humble is to appreciate that when one disagrees with someone, it may not be this other person who is confused and mistaken. We need not deny that all people are created equal in order to concede that some people’s opinions have more to be said for them than others.

I mentioned experience as well as training. A humble person is not only prepared to learn from those with greater expertise. She is also deeply aware of how much can be gained by engaging nonexperts with an open mind and heart. As both Jollimore and Agnes Callard explain, it was this awareness that drove Socrates to seek out others in his quest for wisdom. In different ways, Eranda Jayawickreme and Melissa Koenig and Valerie Tiberius also call our attention to what we miss, and what significant benefits we forego—whether in business or in personal relations—when we presume to know more than the people with whom we interact. Koenig and Tiberius draw a further connection between being open to learning from others and being less prone to treating them in ways that do more harm than good. When, for example, we do not seriously account for the fact that someone’s cares and concerns may be very different (and no less important) than our own, even our benevolent impulses can have harmful effects on those we are trying to help.

Of course, sometimes other people need to learn from us. And having the courage of one’s convictions is just as important as being prepared to modify one’s convictions in response to one’s interactions with others. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche points out that few great deeds would be done, and few great works of art would be created, if people never closed their minds to the many reasons they have for questioning the value of what they are doing. Rick Boothman illustrates this point with his story of how—in the face of powerful opposition—he quit his job as a lawyer defending hospitals against malpractice suits, convincing a major hospital system to incorporate greater humility into the practice of medicine. And Callard stresses the need to combine humility with self-confidence when she notes that the person who is eager to learn from others must rely on the fact that these others have confidence in their own beliefs. In order to expand our knowledge, we must start somewhere. A situation in which everyone suspends her judgments about everything is at least as bad as a situation in which everyone is confident that she has no reason to question her convictions.

Though, as Koenig and Tiberius stress, many of our mistakes reflect the fact that we lack adequate concern for the perspectives of others, our failures can yield lessons in humility even when they cannot be attributed to any such insensitivity. When we fail to achieve our goals, we are often prompted to reconsider how our interests and concerns relate to the interests and concerns of others. In his essay Mickey Duzyj recounts the trajectories of athletes whose public failures—and even humiliations—prompted them to reject their self-involved ambitions and devote themselves to improving the lives of others. As many studies have shown, people who thus redirect their attention and efforts usually end up living far more fulfilling lives as a result.

The connection between being less self-absorbed, on the one hand, and being more generous, on the other, is the theme of Ruth Nicole Brown’s homage to her remarkable Aunt Dottie. Ami Walsh, Kevin Hamilton, Lynette Clemetson, and Jamie Vander Broek each also stress the extent to which a humble person—and as Vander Broek notes, a humble institution—will move into the background in order to enable others to move into the foreground. More particularly, Walsh and Clemetson highlight the humility involved in encouraging people to tell their own stories. And Vander Broek and Hamilton stress the value of supporting the efforts and inquiries of others in ways that involve helping them to follow their own lead.

In effect, this is another respect in which humility involves deference. The same point is central to Gilbert Rodman’s discussion of the way that a just copyright law would facilitate the recognition of artistic contributions that are too often left in the background. In speaking of the indignities of aging, Russell Belk also reminds us how easy it is to treat certain people as unworthy of respect and concern. If, he claims, we are to avoid contributing to the humiliations of those who are old and sick, we must cultivate the qualities identified with humility. This involves, among other things, not privileging the perspective of those who are young and healthy—not treating this perspective as more authoritative, more worthy of being taken seriously and accommodated.

Not only can a humbling experience have a valuable effect; it can also be valuable in itself. This is possible, at any rate, if one’s identity is not tied up with impressing others with one’s knowledge or talents or skills. In short, if one is truly humble, then failure—even public failure—need not be a blow to one’s self-esteem. For this reason, a humble person can adopt a less defensive posture in her relation to others—and even a more playful attitude toward her attempts to realize her goals. Nadia Danienta and Aric Rindfleisch illustrate this point in discussing people who experiment with 3D printing, and who delight in their failures as well as their successes. Humility, these people teach us, is freeing.

Failure is not the only spur to humility. Gaining a deeper appreciation of the fact that we are just one among many can be as simple as appreciating how connected we are to others. To incorporate the sense of oneself as part of a complex web of mutual dependence is to become more humble. At the same time, this humility enhances one’s ability to form bonds with others. In short, retreating from the center of things—both in reality and in one’s self-conception—is inseparable from forging connections that expand the boundaries of one’s self. Several essays in the collection allude to this phenomenon in one way or another. (See, especially, the essays by Jennifer Cole Wright and Ruth Nicole Brown.)

In 1950 a Gallup Poll asked U.S. high school students the question: “Do you think you are an important person?” Only 12 percent of respondents said yes. When the same question was posed in 2006, more than 80 percent said “yes.” This dramatic shift corresponded to a dramatic increase in the value U.S. educators attributed to cultivating self-esteem. These trends raise many questions. Here I will simply note that there is ample evidence that the increase in self-esteem has corresponded to a decrease in humility. The greater tendency to think well of oneself has corresponded to the tendency to think more of—and about—oneself than one thinks of—and about—anyone else.

In her essay Wright offers us a compelling description of what has been lost: not only the benefits that humility confers on us, but also—and more importantly—the distinctive benefit that consists of relating to oneself and the world with humility. In the poem near the end of the collection, Tyler Denmead wonders whether, given his privilege as a white man, he can possibly realize this ideal. Is it really possible to de-center oneself so radically? In seeking an answer to this question, we might start by turning to the last essay in the collection: Kevin Em’s brief account of his transition from the tech world to the world of the restaurant (and then hospital) kitchen. Like Modrak’s summer journeys to Nebraska, this was a transition to a place of greater humility. It was occasioned by Em’s failure to achieve his earlier professional goals. And it was made possible by new connections and dependences, which were, in turn, strengthened by the humility they inspired. Em offers us a portrait of what it is like to be less visible to others, even as one is more attuned to their needs and desires. He describes the greater freedom and generosity that accompany these other changes, and the pride he feels in relating to himself and others in this way. Together with the other essays, this final story prompts us to ask: how might we combine these ingredients in our own lives?