Читать книгу Where in the World is the Berlin Wall? - Группа авторов - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

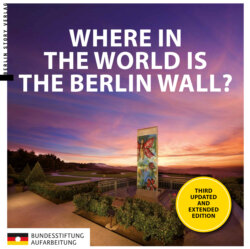

SO WHERE WAS THE WALL?

ОглавлениеThe images from the night of 9th-10th November 1989 are equally as iconic in world history as those from 12th-13th August 1961.

The crowds of people streaming through the open border crossings, sitting and dancing on the crest of the Wall, are as much a part of the public’s memory as the people standing frozen in front of the rolls of barbed wire in 1961 or the residents jumping out of the windows on Bernauer Straße, who saw these lethal jumps as the only way to get to the West and thus to freedom.

Although it was by no means a forgone conclusion to SED rulers in the GDR that the Wall and the border would remain open, deliberations were already being made on 10th November as to what should happen to this “historical monstrosity”. Whilst Willy Brandt – then the reigning mayor of West Berlin – called for sections of the Wall to be preserved as a memorial in his speech in front of the Schöneberg City Hall, others were already thinking of turning the Wall into a business. And so, on 10th November 1989, the first enquiries were sent from Bavaria to the GDR government offering cash in return for “unwanted pieces of your border fortifications no longer needed”.4 Finally, on November 14th, 1989, a business consultant approached the GDR’s Permanent Mission in Bonn and recommended - since the trade in parts of the Berlin Wall could no longer be stopped – that the GDR side should nevertheless consider “with all its ambivalence” that the “trade will be made with sections of the Wall, no matter where they come from. I consider it therefore all the more reasonable to make money from it.”5

Almost overnight, the Wall became a highly sought-after object, a trophy of the Cold War, an export hit and a symbol. If, during its 29 years in existence, the Wall had simply been a symbol of the Socialist system’s inhumanity and oppression, it had become a symbol of civil courage and the will for freedom overnight. No other construction in Germany, and perhaps Europe, had such grave consequences on so many people in the second half of the 20th century. No other construction from this period became a symbol of oppression and dictatorship, contempt for basic human rights and, finally, for taking hostage of millions of people by a regime formed on injustice. After the Fall of the Wall, no other construction went from being a symbol of oppression and contempt for mankind to a symbol of the will for freedom and civil courage.

In the weeks and months after the Wall fell, requests from all over the world for pieces of the Wall increased and on 7th December / 4th January 1990, the GDR government, under Hans Modrow, decided to sell it. It was hoped that selling the Wall would help save the GDR economy which was heading towards bankruptcy. With offers of up to 500,000 Deutsche Mark per section6, these hopes were warranted.

Since the political development by the end of 1989 had already shown that the SED regime could no longer be saved, and, furthermore, that not only the Berlin Wall, but the entire Inner-German border had been opened, dismantling what was once the most heavily guarded border was at the top of the agenda.

It was immediately suggested that at least part of the costs of dismantling the fortifications should be financed by selling the Wall.

The GDR government launched an information campaign around Christmas 1989 to outline the reasons for the sale of the Berlin Wall to the angry and rattled people in the GDR. The campaign aimed to pick up points made in the letters of complaint received by the government and justify the sale of the Wall to which the government saw no alternative.

Anger at the sale of the Wall was directed at the government who had locked in its citizens for decades, ruthlessly shot at escapees and who now wanted to sell this “Wall of shame” – at which people had been murdered – in order to make money. The government used three arguments to justify selling the Wall to the western World:

1) The GDR’s need for foreign exchange,

2) the Wall is public property and, therefore

3) any profit made by the sale would go to the entire GDR population, Social projects, for example, would therefore benefit from such a sale.

Irrespective of any further reservations about the sale of the Wall, the border troops in Berlin-Mitte – whose job had been to protect the Wall and prevent anyone penetrating the border until December 19897 – began work on dismantling the Wall in January 1990. It started with particularly sought-after parts, which had been painted by mural artists. The majority of the concrete sections were crushed and used, amongst other things, for road and motorway construction.

In less than a year, that which once had once separated people along a 156-kilometres-long border and was made up of 54,000 concrete segments – each 2.6 tonnes in weight and 3.2 metres in height – had all but disappeared from the city landscape. Other objects to disappear included hundreds of kilometres of barbed wire and strips of lighting, equipment used to harness guard dogs and 186 watch towers from which guards had shot live-ammunition.

The desire for the city to return to some sort of normality after the long years of division was quite understandable. In 1990, very few could have imagined that there would one day be calls for the city and its people to make their wound visible once more. Removing the Wall from the city completely seemed a suitable way to overcome the division and its consequences as quickly as possible.

It was not only visitors to Berlin, whose interest in the Wall was warranted, who were increasingly perplexedly and asking: “So, where was the Wall?” At the same time, people had to accept that the notion of what the Wall had meant to the city and its people had faded considerably.