Читать книгу Occupy Antigone - Группа авторов - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Antigone’s Transformed Heritage The Limits of Logic: Heidegger’s and Brecht’s Interpretations of Antigone

ОглавлениеFreddie Rokem (Tel Aviv University)

There is (probably) no other literary work in the Western canon that has inspired such a complex and multifaceted tradition of stage productions, adaptations, rewritings, canonized translations, as well as philosophical, psychoanalytical, political, ethical and activist readings as Sophocles’ Antigone. Perhaps only Oedipus the King and Shakespeare’s Hamlet can compete; but not really, at least judging from the constantly growing number of interpretations of Antigone since the turn of the millennium. The conflict between Antigone and her maternal uncle Creon concerning the burial of Antigone’s brother Polyneices after the end of a cruel and devastating civil war, has given rise to a complex, intertextual web of interpretations both on the page and on the stage, where drama, theatre, and performance, on the one hand and philosophy and theory, on the other, interact on a number of levels.1

In what follows I will zoom in on two particular moments of the multifaceted tradition of Antigone readings and productions, during and directly after the Second World War, focusing on the almost contemporaneous, but indeed quite different interpretations of Sophocles’ play: first by Martin Heidegger in his seminar on Hölderlin’s poem The Ister, which he conducted at the University of Freiburg, in the summer of 1942, after his resignation as rector – and not published (in German) until 1984. This particular interpretation was partly based on his previous readings of Sophocles’ play – which includes a detailed interpretation of Hölderlin’s 1804 translation of Antigone – but in this context Heidegger adds some quite remarkable reflections on war and violence. And second, by examining Bertolt Brecht’s adaptation of Hölderlin’s translation, which Brecht directed in Chur, in Switzerland in 1948, six years after the Heidegger seminar and three years after the end of the Second World War. After having spent fifteen years in exile, Antigone – a play about the aftermath of war – was Brecht’s first assignment for the German language stage after the war, leading the following year, in 1949, to the much more known production of Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. Both these Brecht productions, in different ways taking the spectators directly into the ’heart’ of the ’experience’ of war were important steps towards the establishment of the Berliner Ensemble. Soon after his return to Berlin, Brecht also published the book Antigonemodell 1948 in collaboration with Caspar Neher, the scenographer of this production and a close friend since their school days in Augsburg. It was edited (redigiert) by Ruth Berlau, whom Brecht had met in Denmark, during his exile there. She also photographed all of the scenes of the performance that were published in the so-called Modellbuch.

In their foreword to this book, which was to become the first in a series of such publications, laying the basis for an innovative approach to the documentation of Brecht’s own theatre productions and for the understanding of the epic theatre, Brecht and Neher somewhat laconically stated that "[t]he Antigone story was picked for the present theatrical operation as providing a certain topicality of subject matter and posing some interesting formal questions",2 stressing in particular the ways in which the theatre – and this play in particular – reveals "the causality at work in society [my emphasis, FR]",3 adding that, "[e]ven if we felt obliged to do something for a work like Antigone we could only do so by letting the play do something for us".4 It is important to pay attention to how they formulate the dynamics of their engagement with Sophocles’ play, revealing how the "causality" or logic of society is constituted. And only after "letting the play do something for us" will they be able to do something in return for the play. So what does the play do for us? What is the inner logic of Sophocles’ tragedy that enables this reciprocal ’doing’ or ’negotiation’ with this ancient text?

Antigone is a play depicting the anxieties and the threats of a post-war situation, when guilt and responsibility have to be confronted and when there are winners and losers, as well as perpetrators and victims who cannot always be clearly distinguished. For the production in Chur, Brecht composed a short Vorspiel, a prelude, which, as the signboard (fig. 1) written with capital block letters above the stage indicates, takes place in Berlin, an early morning in April 1945 at the time when a new day breaks. In this short scene with two unnamed sisters returning from the air-raid shelter discovering traces of someone who has entered their home, leaving food for them. Brecht’s wife Helene Weigel, who played the First Sister in the dark coat and will then play Antigone in Sophocles’ play and Marita Glenk as the Second Sister in the white coat, who will then be Antigone’s sister Ismene in the play itself, immediately following the Vorspiel, realize – when it is already too late – that it is their brother who has made a short visit to their home, bringing the much needed food.

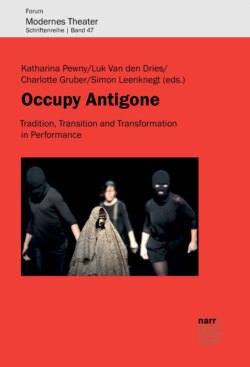

Fig. 1

Bertolt Brecht’s Antigone (1948) in Chur, Switzerland. Credits: Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Bertolt-Brecht-Archiv Theaterdoku 318/317, © R. Berlau/Hoffmann.

As their happiness from this unexpected fortune was growing, they hear a scream from the outside and an SS officer who can also be seen in the photo enters the room and interrogates them about the identity of the man that had been seen coming out through the door of their house and who had then been killed by hanging. The two sisters deny that they recognize this dead soldier – who is actually their brother – just as Mutter Courage denies knowing her own son Swiss Cheese when he is brought onto the stage on a stretcher after he had been executed for having stolen the cash-box of the Finnish Regiment. In Mutter Courage the mother bargains too long for the life of her son, trying to sell her wagon. And after the soldiers have left with her dead son, Courage/Weigel opens her mouth in what has become her renowned silent scream. In Brecht’s Antigone, the sisters are not given any opportunity to prevent the execution of their brother. In Sophocles’ original play, however, as opposed to the two situations of denial for the sake of survival that Brecht presented, Antigone never denies that she has buried her brother, creating a stark contrast between the Vorspiel and the ancient tragedy.