Читать книгу Black Panther and Philosophy - Группа авторов - Страница 8

ОглавлениеIntroduction A Few Words from the Wakandan International Outreach Centre

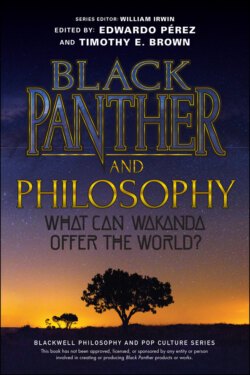

Edwardo Pérez and Timothy E. Brown

When the character of Black Panther first appeared in Fantastic Four no. 52 in July 1966, legendary creators Stan Lee and Jack Kirby didn’t just write a story about another hero with extraordinary powers, they birthed the first Black superhero. For Lee, “it was a very normal thing,” because “A good many of our people here in America are not white. You’ve got to recognize that and you’ve got to include them in whatever you do.”1

While it might’ve seemed normal to Lee, Black Panther’s (and Wakanda’s) significance cannot be overstated. After all, the first Black superhero isn’t just a Black superhero, he’s the King of an African nation endowed with otherworldly powers, and Wakanda isn’t just an African nation, it’s the most advanced civilization the Earth has ever seen. Indeed, it shouldn’t be lost on us that when Black Panther was introduced (during the Civil Rights era of the 1960s) the thought of a Black President – or an advanced, futuristic African society – would have been, well, unthinkable for too many people.

Perhaps Stan was being modest. Or, perhaps Stan was just being Stan, using his platform, his voice, and his characters to tackle the issues of society in a way only superheroes in comics can. Indeed, one of the most noteworthy columns Stan published, tackling social issues, was a “Stan’s Soapbox” in 1968 that began with the following statement:

Let’s lay it right on the line. Bigotry and racism are among the deadliest social ills plaguing the world today. But, unlike a team of costumed super-villains, they can’t be halted with a punch in the snoot, or a zap from a ray gun. The only way to destroy them is to expose them – to reveal them for the insidious evils they really are.2

And ended with the following words:

[…] Sooner or later, we must learn to judge each other on our own merits. Sooner or later, if man is ever to be worthy of his destiny, we must fill our hearts with tolerance. For then, and only then, will we be truly worthy of the concept that man was created in the image of God – a God who calls us ALL – His children.3

It’s a powerful column, one that not only resonates with the issues of today’s world, but that also reflects the message of Ryan Coogler’s 2018 film: that we are all “one single tribe.”

Of course, to be fair, Black Panther isn’t a perfect hero and Wakanda isn’t a perfect nation. T’Challa recognizes this in the film and so do the contributors of this volume, who analyze the character of Black Panther and the nation of Wakanda (seen in the film and comics) with a critical, philosophical eye, tackling issues of racism, colonialism, slavery, sexuality, feminism, politics, morality, spirituality, Afrofuturism, technology, and the wonders of vibranium with a mixture of insight and humor that not only reflects the nature of this philosophical series, but that also honors the tradition Stan (and Jack) started all those years ago.

Yibambe!

Ed and Tim

Notes

1 1. Joshua Ostroff, “Marvel comics icon Stan Lee talks superhero diversity and creating Black Panther,” Huffington Post, September 1, 2016, at https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2016/09/01/stan-lee-marvel-superhero-diversity_n_11198460.html.

2 2. Stan Lee on Instagram: “Stan’s Soapbox, 1968,” at https://www.instagram.com/p/CBBlrsOp3Ox/?hl=en-gb.

3 3. Lee.