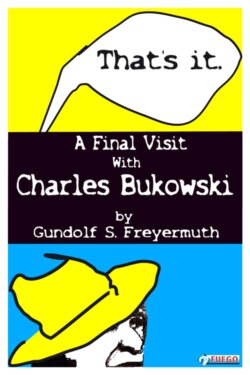

Читать книгу That's It. A Final Visit With Charles Bukowski - Gundolf S. Freyermuth - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVI

“Like a spider spins a web.”

- Bukowski on Writing -

“‘The sun is in agonyeee in Saint Louiiiie’, or something weird like that I used to put into my early poems. You know, I would write a poem, most of it would be me, but then I threw them a line they wanted: Suck on that! ‘Cause I knew that the editors liked their poetry a little bit poetic and not so hard like my lines. So I gave them ... I mean, most of the lines were mine. I would just throw them a little bait. Which I shouldn’t have done. But I did. And then I got rid of the poem. So ... That’s it?”

“I haven’t asked a single question yet ...”

“Okay, go on ...”

We are sitting in the little yard Charles Bukowski calls his “garden of Eden.” A few feet away the silhouettes of two wooden boxers driven by the wind are attacking each other. The toy is Michael Montfort’s birthday present for Bukowski. The old man watches the restless fight and grins.

“I bet the next thing you want to know is why I write?” he says. “Yeah? Of course, I thought so ... I do it for the same reason now I did it then. So that I don’t go totally mad. The reason is the same. But now I get paid for it. And then I didn’t.”

“For me to get paid for writing is like going to bed with a beautiful woman,” he once noted, “and afterwards she gets up, goes to her purse and gives me a handful of money. I’ll take it.”

“All that money,” I ask, “is it really good for what you write?”

“Of course, it’s better. I’d rather have a little,” Bukowski says. “I starved many, many years. I starved, and starved, and starved. I mean, it’s alright. But it’s wearing. You get thin, and your teeth fall out. I could just pull my own teeth out of my mouth. Just pull one out and throw it on the floor. Starvation. Then all parts weaken.” He pauses. “Okay, I starved. I don’t mind not starving. I put in my time on that. I don’t feel guilty.”

“You said you wrote in order not to go mad ...”

“Not going crazy. Yeah ...”

“And?” I ask: “Did it help?”

“You think I am crazy? That it did not help?” He chuckles. “Think, if I hadn’t written all that! I mean, I’d probably be in some padded cell. I think so. It’s a relief ... That’s it? No?”

He takes a deep breath and points to Michael Montfort who whirls around us letting the motor of his camera whirr.

“If he says something interesting,” Bukowski says, “just pretend that it was me ...”

“Sure,” I nod. “On the other hand, it’s not that important. I will make up the quotes anyhow.”

“Oh well,” Bukowski says, “it’ll be fine with me. But listen, just in case you can’t come up with something, I’ll tell you a story about writing ...” With a tired gesture, he chases a fly off the age marked back of his hand: “Once I was starving, in a shack in Atlanta. I didn’t have a typewriter. But I found a little stub of a pencil, and with that stub of a pencil there were newspapers on the floor. I wrote on these edges of the newspapers; that was all the paper I had. So I knew, nobody would ever read what I wrote, but I had to write. It was like a spider spins a web, you know. So, I am a natural born writer. I wanna write. It’s a thing I can’t explain. It’s deep in me. There is nothing I can do about it; except do it; and then I’m relieved ...”

“Do you still remember what you have written then?”

“In that shack? Oh, no ...! Not a word ...”

“I once knew a writer who in 1940, on his flight before the Nazis, had been kept prisoner in a French camp,” I relate: “There he wrote his poems just like you - with the stub of a pencil on scraps of paper. And half a century later, when he was almost ninety and blinded of old age, the recovered texts were archived, and there was nobody who could read his hand writing ...”

“Well, there you go,” Bukowski says, “makes no sense to keep stuff like that ...”

“The story isn’t over yet: The old man - his name was Hans Sahl, I met him in New York - still knew each line by heart. ‘What one has written with the stub of a pencil on notepaper for which one had to trade in two cigarettes in the camps,’ he said, ‘something like that one will not forget.’”

“Good,” Bukowski says without a smile. “He is lucky. ‘Cause I forget everything I write.”

“Isn’t that the reason why we write something down?”

“Yeah. It’s easier to forget. People ask me about words in my books. I say: ‘What? Did I write that?’ I think it’s best that you clean it out so that you can write the new thing. It’s like a new beginning ...”

For a moment Bukowski moves sinuously in the garden chair. Then he reaches for his straw hat, which protects him against the California sun, and tilts it at an obtuse angle almost covering his eyes.

“That’s it?” he asks.

“I wonder how often I will let you say ‘that’s it’ before I say ‘yes.’”

“Yeah, I wonder too ...,” Bukowski laughs good-humoredly: “What now? Hemingway?”

“Not yet. He is my last resort. If I can’t think of anything else.”

“Well,” Bukowski says, “there we have something really great to look forward to.”