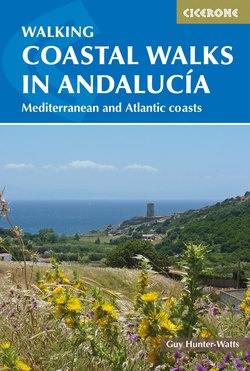

Читать книгу Coastal Walks in Andalucia - Guy Hunter-Watts - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Approaching Puerto de Málaga (Costa del Sol, Walk 23)

Talk to most people about the coast of Andalucía and they’ll picture the small swathe of seaboard that runs from Torremolinos to Estepona, the heartland of what is commonly sold as the Costa del Sol. First associations are of crowded beaches, busy coastal roads and blocks of holiday apartments. Few will conjure up visions of the mighty chain of mountains, the tail end of the Sierra Subbética, which rises up a few kilometres back from the sea. Nor do they tend to evoke the wilder beaches of the Costa de la Luz or the footpaths that run just a few metres from the Atlantic surf.

Since Iberian times these coastal paths have seen the passage of livestock, charcoal, fruit and vegetables, dried fish, ice from the high sierras, silks and spices from distant lands, contraband coffee and tobacco along with muleteers and shepherds, itinerant workers, fortune seekers and armies on the march. Ancient byways have a logic of their own and when researching this book I was constantly struck by a sense of Times Past, and not only when a section of ancient paving or cobbled path suggested Roman or Arabic origins. This sense of history, and of continuity, gives nearly all the walks described in this book an added appeal. It’s as if these ancient byways serve to reconnect us with something that has been around since time immemorial but which we rarely get the chance to experience.

If the areas described in the book share a common historical thread the different parts of the Costa have their own unique character. The cliffs, pine forests and marshlands close to Vejer are very different in feel to the wooded slopes of the Algeciras hinterland with its unique canuto (gorge) ecosystem. The lunaresque landscapes of the Sierra Bermeja stand in marked contrast to the forested mountainsides behind Marbella and Mijas, while the cliffs and crumpled massif of the sierras between Nerja and Almuñecar have a beauty all of their own, as do the mineral landscapes of Cabo de Gata. Each region is described in greater detail in its corresponding section but – rest assured – there’s superb walking in every one of them.

There are many terms to describe a protected area in Andalucía: Unesco Biosphere Reserve, Parque Natural, Paraje Natural and so on. All seven coastal regions described fall into one of these categories apart from the Sierra de Mijas which is soon to gain protected status. If all of these areas now have some form of waymarking in place, this only partially covers the routes described in this book and in many cases marker posts are damaged or missing. But with the map sections and walking notes, and the GPS tracks if you use them, you’ll have no problems in finding your way.

The walks in this book are generally one of three types. There are walks which link different coastal villages, others which are circular itineraries which involve some walking at the ocean’s edge, and a third group of inland circuits and gorge walks just a few kilometres back from the sea. At some point during all of the walks you’ll be treated to vistas of the Atlantic or the Mediterranean.

Seven coastal regions

The different walking areas are arranged in seven sections which correspond to the different Natural Parks and protected areas, or combinations of them. In just a few instances the walks described fall just outside official park boundaries, while the Sierra de Míjas will soon be officially declared a protected area. At the beginning of each chapter you’ll find a more detailed overview of each area. The brief description that follows will give an idea of the kind of walking and terrain you can expect to encounter. The first two Natural Parks are on the Costa de la Luz, the next three are on the Costa de la Sol.

La Breña y las Marismas

Walkway leading to La Playa de Zahora near Cape Trafalgar (Costa de la Luz, Walk 5)

The five walks listed are all close to the towns of Vejer, Conil, Los Caños de Meca and Zahara de los Atunes. Most walks follow footpaths very close to the ocean apart from the Marismas circuit, a marsh walk just a few kilometres inland, and the Santa Lucía circuit which is a fifteen-minute drive from the ocean and explores the hills north of Vejer. Gradients are generally gentle in the coastal hinterland while sea breezes help make even summer walking enjoyable.

Los Alcornocales y del Estrecho

The five walks described are close to Los Barrios, Pelayo, Bolonia and Gibraltar. I’ve listed a Gibraltar walk in a southern Spanish walking guide because it’s a stunning excursion and easy to access. Three walks follow footpaths along the ocean’s edge while the other two, which involve more climbing, introduce you to the beautiful southern flank of the Alcornocales park and its unique canuto ecosystem.

La Sierra Bermeja y Sierra Crestellina

Casares seen from the east (Costa del Sol, Walk 13)

Of the five walks listed, two lead out from Casares, one from close to the village and another from a point just north of Manilva while the Pico Reales circuit involves a short drive north from Estepona. Although all walks lie a few kilometres inland you can expect incredible views of the Mediterranean, Morocco and Gibraltar. Be prepared for sections of steepish climbing on all walks although none are graded ‘difficult’.

La Sierra de las Nieves

Of the six walks described one leads out from Marbella and two from El Refugio de Juanar while three hikes begin in the pretty mountain village of Istán. Most walks involve steep sections of climbing though two are quite short in distance. The magnificent Concha ascent is one of the few walks within these pages for which a head for heights is required and there are a couple of points where you’ll need to use your hands as well as your feet.

La Sierra de Mijas

The six walks described begin in the villages of Mijas, Benalmádena, Alhaurín de la Torre and Alhaurín el Grande and lead you to the most beautiful corners of the compact, yet stunningly varied landscape of the Sierra de Mijas. All walks involve sections of steep climbing, while all are easy to follow thanks to the recent waymarking of the local PR and GR footpaths.

La Sierra de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama

Looking north into the Higuerón gorge (Costa Tropical, Walk 30)

The villages of Cómpeta, Canillas de Aceituno and Frigiliana are all situated high on the southern flank of the Sierra de Almijara on the Costa Tropical. All three look out to the Mediterranean and their history and economy have always been inextricably linked to that of the coast. The Maroma ascent, the Imán trail and the Blanquillo circuit are big, full-day walks, the exhilarating gorge walk just inland from Nerja is not be missed while the La Herradura circuit leads you past two of the Costa Tropical’s most beautiful beaches.

Níjar-Cabo de Gata

The volcanic landscapes of the Cabo de Gata region on the Costa de Almería are unique to southern Spain and walks here have a haunting beauty all of their own. In all but the summer months you can expect to meet with few other walkers and the small coastal villages of Agua Amarga, Las Negras and San José have a great range of accommodation for all budgets. The best time of year to be here is spring, when the desert-like landscapes briefly take on a hue of green while in winter this is the region of Andalucía where you’re most likely to see warm and sunny weather.

Plants and wildlife

Two major highlights of any walk in southern Spain come in the form of the flowers and birds you see along the way.

Andalucía is among the best birding destinations in Europe and ornithological tourism has grown rapidly in recent years. The best time for birdwatching is during the spring and autumn migrations between Europe and North Africa, but at any time, in all parks covered in this guide, you can expect rich bird life. As well as seasonal visitors there are more than 250 species present throughout the year.

The marshes close to Barbate is one of the best sites in southern Spain for observing wading birds, both sedentary and migratory, while at the eastern end of Andalucía the salt flats of the Cabo de Gata Natural Park provide a superb observatory for wader and duck species such as ibis, spoonbills and coots as well as greater flamingos.

(clockwise from top) Griffon Vulture, Bee-eater and Crested Lark (images courtesy of Richard Cash of Alto Aragón)

One of Europe’s most remarkable wildlife events are the annual migrations across the Strait of Gibraltar. This offers the chance to observe thousands of raptors including Egyptian, griffon and black vultures; golden, imperial, booted and Bonelli’s eagles; honey buzzards and harriers as well as storks and smaller passerines. The birds circle up on the thermal currents then glide between the two continents. The migration into Spain takes place between February and May while birds heading south can be seen from August through to late October.

If you’d like a list of the more common species, visit www.cicerone.co.uk/803/resources.

For further information about birding resources and organised birding tours and walks, see Appendix B (Useful contacts).

Wildflowers in spring

The southern coastline also offers rich rewards for botanists. Forty per cent of all species found in Iberia are present in Andalucía and many of these grow in the coastal region. The annual wildflower explosion in late spring is as good as any in southern Europe, especially in areas where the rural exodus has ensured that much of the land has never seen the use of pesticides. For a list of 300 of the more common species, with common and Latin names, visit www.cicerone.co.uk/803/resources.

Vertebrates are less easy to spot but are also present. Along with the grazing goats, sheep, cattle and Iberian pigs you may see squirrels, hares, rabbits, deer, wild boar, otters and mongoose. Ibex (Capra pyrenaica hispánica) are making a rapid comeback in many of the regions described here, especially so in the Sierra de Tejeda and on the southern flank of the Sierra de Ojén. And on the Gibraltar walk you’ll certainly have close encounters with Barbary apes as you follow the high ridgeline from O’Hara’s Battery.

Close encounter of the bovine kind in the Breña forest (Costa de la Luz, Walk 4)

Andalucía has a long roll call of reptiles. Of its many species of snakes just one is poisonous, the Lataste’s viper, which is rarely seen in the coastal areas. Iberian and wall lizards are common, as are chameleons, while the much larger ocellated lizard can often be seen near the coast and especially along the ramblas (dry river beds) of Cabo de Gata.

Appendix E (Further reading) includes details of guidebooks that will help you to identify the plants and wildlife of Andalucía.

Andalucía over the years

Anyone who’s travelled to other parts of the Iberian Peninsula will be aware of the marked differences between the regions of Spain and its peoples. If Franco sought to impose a centralist and authoritarian system of government on his people, the New Spain, ushered in with his departure and the advent of liberal democracy, actively celebrates the country’s diverse, multilingual and multi-faceted culture.

But if Spain is diferente, as the marketing campaigns of the 90s and noughties would have us believe, then Andalucía is even more so. It is, of course, about much more than the stereotypical images of flamenco, fiestas, castanets, flounced dresses, sherry and bullfighting: any attempt to define what constitutes the Andaluz character must probe far deeper. But what very quickly becomes apparent on any visit to the region is that this is a place of ebullience, joie de vivre, easy conversation and generous gestures. The typical Andalusian’s first loves are family, friends and his or her patria chica (homeland), and it’s rare to meet one that isn’t happy to share it all with outsiders.

What goes to make such openness of character is inextricably linked to the region’s history and its geographical position at the extreme south of Europe, looking east to Europe, west to the Atlantic and with just a short stretch of water separating its southernmost tip from Africa. This is a land at the crossroads between two continents, at the same time part of one of the richest spheres of trade the world has ever known: the Mediterranean Basin. Visitors from faraway places are nothing new!

Roman ruins on the Atlantic Coast near Tarifa

A thousand years before Christ, the minerals and rich agricultural lands of Andalucía had already attracted the interest of the Phoenicians, who established trading posts in Málaga and Cádiz. But it was under the Romans, who ruled Spain from the 3rd century BC to the 5th century AD, that the region began to take on its present-day character. They established copper and silver mines, planted olives and vines, cleared land for agriculture and built towns, roads, aqueducts, bridges, theatres and baths while imposing their native language and customs. Incursions by Vandals and then Visigoths ended their rule, but its legacy was to be both rich and enduring.

The arrival of the Moors

If Rome laid the foundations of Andalusian society in its broadest sense, they were shallow in comparison to those that would be bequeathed in the wake of the expeditionary force that sailed across the Strait in 711 under the Moorish commander Tariq.

After the death of the Prophet, Islam had spread rapidly through the Middle East and across the north of Africa, and the time was ripe for taking it into Europe. Landing close to Gibraltar, Tariq’s army decisively defeated the ruling Visigoths in their first encounter. What had been little more than a loose confederation of tribes, deprived of their ruler, offered little resistance to the advance of Islam across Spain. It was only when Charles Martel defeated the Moorish army close to the banks of the Loire in 732 that the tide began to turn and the Moors looked to consolidate their conquests rather than venture deeper into Europe.

A first great capital was established at Toledo, and it became clear that the Moors had no plans to leave in a hurry: Andalucía was to become part of an Islamic state for almost eight centuries.

The cathedral of Santa Maria in Ronda which has an Arab minaret as its bell tower

Moorish Spain’s Golden Age took hold in the 8th century, when Jews, Christians and Moors established a modus vivendi the likes of which has rarely been replicated, and which yielded one of the richest artistic periods Europe has known. Philosophers, musicians, poets, mathematicians and astronomers from all three religions helped establish Córdoba as a centre for learning second to no other in the West, at the centre of a trading network that stretched from Africa to the Middle East and through Spain to northern Europe.

However, the Moorish Kingdom was always under threat, and the Reconquest – a process that was to last more than 800 years – gradually gained momentum as the Christian kingdoms of central and northern Spain became more unified. Córdoba fell in 1031, Sevilla in 1248, and the great Caliphate splintered into a number of smaller taifa kingdoms.

The Moors clung on for another 250 years, but the settlements along la frontera fell in the early 1480s, Ronda in 1485, Málaga and Vélez in 1487, and finally Granada in 1492. The whole of Spain was once again under Christian rule.

Spain’s Golden Age

If ever anybody was in the right place at the right time – that’s to say in the Christian camp at Santa Fe when Granada capitulated – it was the Genoese adventurer Cristóbal Colon, aka Christopher Columbus. His petition to the Catholic monarchs for funding for an expedition to sail west in order to reach the East fell on fertile soil.

The discovery of America, and along with it the fabulous riches that would make their way back to a Spain newly united under Habsburg rule, was to usher in Spain’s Siglo de Oro or Golden Age. Spain’s Empire would soon stretch from the Caribbean through Central and South America and on to the Philippines; riches flowed back from the colonies at a time when Sevilla and Cádiz numbered among the wealthiest cities in Europe. The most obvious manifestation of this wealth, and nowhere more so than in Andalucía, were the palaces, churches, monasteries and convents that were built during this period: never again would the country see such generous patronage of the Arts.

However, by the end of the 16th century Spain’s position at the centre of the world stage was under threat. A series of wars in Europe depleted Spain’s credibility as well as the state coffers: by the late 17th century Spanish power was in free fall. It remained a spent force into the 19th century, and yet further violent conflict in the early 20th century led to General Francisco Franco (‘El Caudillo’) sweeping into power in 1936.

Franco’s crusade

Franco’s ‘crusade’ to re-establish the traditional order in Spain – the Spanish Civil War – lasted three years, during which an estimated 500,000 Spaniards lost their lives. The eventual victory of the Nationalists in 1939 led to Franco’s consolidation and centralisation of power and the establishment of an authoritarian state that remained until his death in 1975.

A monument to victims of the Civil War close to Ronda

Franco had hoped that King Juan Carlos, who he’d appointed as his successor prior to his death, would continue to govern much in his image; but the young king knew which way the tide was running and immediately began to facilitate the creation of a new constitution for Spain and, along with it, parliamentary democracy. Andalucía, as was the case for several other regions of Spain, saw the creation of an autonomous Junta, or government, based in Sevilla.

The 80s, 90s and noughties were very good years for Andalucía, during which it saw its infrastructure rapidly transformed. New roads, schools, hospitals and hotels were built, along with a high-speed train line from Sevilla to Madrid. The huge construction boom put money into many a working person’s pocket; Andalucía had never had it so good.

Tourism continues to be a major motor of the Andalusian economy, along with the construction industry, fuelled by ex-pats setting up home in the south and other foreigners buying holiday homes and flats. But the economic downturn has hit the region hard and Andalucía currently has an unemployment rate among its adult workforce of almost 35% – the highest in Spain – while among young people that percentage is almost double.

However, at the time of writing (spring 2016) there are signs that the building industry – a major part of the region’s beleaguered economy and a yardstick for the rest of the economy – is beginning to recover, and that a naturally optimistic people are beginning to believe that the worst is behind them. ¡Viva Andalucía!

Getting there

The rocky eastern flank of La Crestellina (Cost del Sol, Walk 12)

By air

For walks on the Atlantic Coast the best choice of airports are Sevilla, Jerez and Gibraltar. The latter two are also within easy range of the western Costa del Sol while Málaga is the better choice for walks close to Marbella, Mijas and the Costa Tropical. Málaga also has charter flights from all major cities in the UK as well as scheduled flights with British Airlines and Iberia. The nearest airports to Cabo de Gata, at the eastern end of Andalucía, are those at Granada, Almería and Murcia.

By car

Car hire in Spain is inexpensive when compared to that in other European destinations, and all the major companies are represented at all airports. Prices for car hire from Málaga tend to be lower. Public transport is surprisingly limited in the coastal area so hiring a car will make trip planning much easier, especially when trailheads are away from the village centres.

By train and bus

None of the seven regions described have direct access to the rail network. It is possible to travel by train to Jerez, Cádiz, Málaga or Almería and then travel on by bus or taxi to the different parks. Bus transport along the Atlantic Coast is more limited than that along the Mediterranean Coast while this is even more so within Cabo de Gata.

When to go

As a general rule, the best time to walk in Andalucía is from March through to June and from September to late October. This is when you’re likely to encounter mild, sunny weather: warm enough to dine al fresco yet not so hot as to make temperature an additional challenge. Wildflowers are at their best in late April/early May and this is the time when many walking companies plan their walks.

Most walkers avoid July and August when temperatures regularly reach the mid to high 30s, making walking much more of a challenge. That said, if you limit yourself to shorter circuits, get going early and take plenty of water you can still enjoy walking in high summer.

If you’re prepared to risk seeing some rain then winter is a wonderful time to be out walking, especially from December to February when rainfall is generally less than in November, March and April. ‘Generally’ means exactly that: rainfall statistics for the past century confirm winter’s relative dryness – although the past two decades, with two prolonged droughts followed by some unusually wet winters, provide no steady yardstick on which to base your predictions. The most obvious choice for winter walking is Cabo de Gata: it’s one of the driest areas in Europe and has many more hours of winter sunshine than other areas in southern Spain.

When planning excursions to the Atlantic Coast close to Tarifa it’s always worth checking to see if levante winds are expected. When the wind is blowing hard through the Strait, beach walking can become a real battle against the whipped up sands.

It’s always worth checking out one of the better wind websites like www.windguru.cz

Accommodation

La Plaza de España, Vejer de la Frontera (Costa de la Luz, Walk 3)

If Andalusian tourism was once all about traditional beach and hotel tourism the past 30 years have seen a huge growth in the numbers of visitors who come to discover its walking trails. Villages just back from the coast tend to be the best first choice when it comes to small hotel and B&B style accommodation where prices are generally low in comparison to the hotels of the coastal resorts. As a rule of thumb, for €50–€70 you should be able to find a decent hotel room for two with its own bath or shower room, and breakfast will often be included.

The contact details of recommended hotels, hostels and B&Bs in and around the villages where walks begin or end are listed, by region, in Appendix C. All of the places have been visited by the author and all are clean and welcoming. Most listings offer breakfast as well as evening meals while some can also prepare picnics given prior warning.

Nearly every hotel in Andalucía is listed on www.booking.com, where, in theory, you’ll always get the lowest price. Bear in mind, though, that by contacting the hotel directly you’ll be saving them the commission they’d pay to the website, so they’re sometimes happy to cut out the third party and offer a lower price. Hotels may also have special offers posted on their own websites. However, both booking.com and TripAdvisor (www.tripadvisor.co.uk) can be a good starting point if you wish to read about other guests’ experiences at any given place.

Hotels in Andalucía make extensive use of marble. It’s a perfect material for the searing heat of the summer, but in winter marble floors can be icy cold. Pack a pair of slippers: they can be a godsend if travelling when the weather is cold. And when sleeping in budget options during cold weather it’s worth ringing ahead to ask the owners if they’d mind switching on the heating before your arrival. Remember, too, that cheaper hostels often don’t provide soap or shampoo.

When checking in at hotel receptions expect to be asked for your passport. Once details have been noted down, Spanish law requires that it’s returned to you.

Eating out in southern Spain

The footpath as you approach the Tajo del Caballo (Costa del Sol, Walk 24)

Although it may not be known as a gourmet destination, you can eat very well in Andalucía if you’re prepared to leave a few of your preconceptions at home. Much of the food on the menu in most mountain village restaurants is stored in a deep freezer and microwaved when ordered – the exceptions to the rule being the freshly prepared tapas that you’ll see displayed in a glass cabinet in nearly every bar and restaurant. These can provide a delicious meal in themselves.

A tapa (taking its name from the lid or ‘tapa’ that once covered the jars in which they were stored) has come to mean a saucer-sized plate of any one dish, served to accompany an apéritif before lunch or dinner. If you wish to have more of any particular tapa you can order a ración (a large plateful) or a media ración (half that amount). Two or three raciónes shared between two, along with a mixed salad, would make a substantial and inexpensive meal.

When eating à la carte don’t expect there to be much in the way of vegetables served with any meal: they just don’t tend to figure in Andalusian cuisine. However, no meal in southern Spain is complete without some form of salad, which is where Andalusians get their vitamin intake. And fresh fruit is always available as a dessert.

Bear in mind that there’s always a menú del día (set menu) available at lunchtime – even if waiters will try to push you towards eating à la carte – and as a result of the recent economic downturn many restaurants now also offer the menú del día in the evenings. Although you have less choice – generally two or three starters, mains and desserts – the fact that set menus are often prepared on the day, using fresh rather than frozen ingredients, means this can often be the best way to eat.

Expect to pay between €8 and €10 for a three-course set menu which normally includes a soft drink, a beer or a glass of wine. When eating à la carte in most village restaurants you can expect to pay around €20–€25 per head for a three-course meal including beverages, while a tapas-style meal would be slightly less. Tipping after a meal is common although no offence will be taken should you not leave a gratuity when paying smaller sums for drinks at bars.

The southern Spanish eat much later than is the custom in northern Europe. Lunch is not generally available until 2.00pm and restaurants rarely open before 8.00pm. A common lament among walkers is that breakfast is often not served at hotels until 9.00am, although village bars are often open from 8am. If you’re keen to make an early start, pack a Thermos. Most hotels will be happy to fill it the night before, and you can always buy the makings of your own breakfast from a village shop.

Breakfasts in hotels can be disappointing, so I often head out to a local bar. Most serve far better coffee than you’ll get at a hotel, freshly squeezed rather than boxed orange juice, and una tostada con aceite y tomate – toast served with tomato and olive oil – can be a great way to start your walking day.

When shopping for the makings of your picnic, be aware that village shops are generally open from 9.00am–2.00pm and then 5.30pm–8.30pm. Many smaller shops will be happy to make you up a bocadillo or sandwich using the ingredients of your choice.

Language

Visitors to Andalucía often express surprise at how little English is spoken, where even in restaurants and hotels a working knowledge of English is the exception rather than the norm. In addition, the Spanish spoken in southern Spain – Andaluz – can be difficult to understand even if you have a command of basic Spanish: it’s spoken at lightning speed, with the end of words often left unpronounced.

Appendix D offers translation of some key words that you may see on signs or maps or need to ask directions but it’s worth picking up a phrasebook before you travel – and be prepared to gesticulate: you always get there in the end.

Money

Most travellers to Spain still consider that the cost of their holiday essentials – food, travel and accommodation – is considerably lower than in northern Europe. You can still find a decent meal for two, with drinks, for around €30; and €60 should buy you a comfortable hotel room for two.

Nearly every start point village in this guide has an ATM, and where this is absent you’ll generally be able to pay in shops, restaurants and hotels with a credit card (although you may be asked for some form of identity that matches the name on your card). Be aware that you’ll often be asked for your credit card details when booking a hotel room by phone.

Communications

While most of Spain now has good mobile coverage for all major phone operators, there are still a few gaps in some of the coastal valleys – which is exactly where many of these walks will be taking you! Even so, it’s always wise to have a charged phone in your daypack, preloaded with emergency contact numbers (see Appendix B, Useful contacts).

Wifi coverage is available in most hotels and is nearly always free of charge for patrons.

What to take

Cairn at the summit of La Concha (Costa del Sol, Walk 20)

The two most important things to take with you when you walk in Andalucía are:

water – always carry plenty of water. During the warmer months the greatest potential dangers are heat exhaustion and dehydration. Wear loose-fitting clothes and a hat, and keep drinking.

comfortable, broken-in walking boots – no walk is enjoyable when you’ve got blisters.

With safety in mind, you should also carry the following:

hat and sun block

map and compass

Swiss Army Knife or similar

torch and whistle

fully charged mobile phone (even though coverage can be patchy in the mountains)

waterproofs, according to season

fleece or jumper (temperatures can drop rapidly at the top of the higher passes)

first aid kit including antihistamine cream, plasters, bandage, plastic skin for blisters

water purifying tablets

chocolate/sweets or glucose tablets

handheld GPS device (if you have one)

Maps

Under each general section I’ve recommended the best map available for the area, Appendix B includes the full contact details of companies from which you can buy these maps. All of the Spanish retailers will send maps contra reembolso (payment on receipt) to addresses within Spain.

In Andalucía the best places to order maps are LTC in Sevilla (www.ltcideas.es/index.php/mapas) and Mapas y Compañia in Málaga (www.mapasycia.es); in Madrid the best places are La Tienda Verde (www.tiendaverde.es) and Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica (www.cnig.es). In the UK the best place for maps, which can be ordered online, is Stanfords (www.stanfords.co.uk).

Staying safe

When heading off on any walk, always let at least one person know where you’re going and the time at which you expect to return.

Log the following emergency telephone numbers into your mobile:

112 Emergency services general number

062 Guardía Civil (police)

061 Medical emergencies

080 Fire brigade

In addition to the usual precautions you would take, there are a few things to remember when walking in Andalucía:

Water – be aware that in dry years some of the springs that are mentioned in this guide can slow to little more than a trickle or dry up altogether. Always carry plenty of water. I’d also recommend keeping a supply of water purification tablets in your daypack.

Fire – in the dry months the hillsides of Andalucía become a vast tinderbox. Be very careful if you smoke or use a camping stove.

Hunting areas – signs for ‘coto’ or ‘coto privado de caza’ designate an area where hunting is permitted in season and not that you’re entering private property. Cotos are normally marked by a small rectangular sign divided into a white-and-black triangle.

Close all gates – you’ll come across some extraordinary gate-closing devices! They can take time, patience and effort to open and close.

Using this guide

Waymarking for the local network of footpaths

The 40 walks in this guide are divided into seven sections, each covering a different coastal region of Andalucía. For each region there is a mixture of half-day and full-day walks that will introduce you to the most attractive areas of the particular park and lead you to its most interesting villages. The route summary table included as Appendix A will help you select the right routes for your location, timeframe and ability.

The sections begin with a description of the area, including information about its geography, plants and wildlife, climate and culture. This is followed by details of accommodation, tourist information and maps relevant to the walks described in the section.

The information boxes at the start of each walk provide the essential statistics: start point (and finish point if the walk is linear), total distance covered, ascent and descent, grade or rating, and estimated walking time. They also include, where relevant, notes on transport and access, and en route refreshments options (not including springs). The subsequent walk introduction gives you a feel for what any given itinerary involves.

The route description, together with the individual route map, should allow you to follow these walks without difficulty. Places and features on the map are highlighted in bold in the route description to aid navigation. However, you should always carry a compass and, ideally, the recommended map of the area; and a handheld GPS device is always an excellent second point of reference (see ‘GPS tracks’, below).

Water springs have been included in the route descriptions but bear in mind that following periods of drought they may be all but non-existent.

Rating

Walks are graded as follows:

Easy – shorter walks with little height gain

Easy/Medium – mid-length walks with little steep climbing

Medium – mid-length walks with some steep up and downhill sections

Medium/Difficult – longer routes with a number of steep up and downhill sections.

If you’re reasonably fit you should experience no difficulty with any of these routes. For walks classed as Medium/Difficult, the most important thing is to allow plenty of time and take a good supply of water. And remember that what can be an easy walk in cooler weather becomes a much more difficult challenge in the heat. This rating system assumes the sort of weather you’re likely to encounter in winter, spring or autumn in Andalucía.

Time

These timings are based on an average walking pace, without breaks. You’ll soon see if it equates roughly to your own pace, and can then adjust timings accordingly. On all routes you should allow at least an additional hour and a half if you intend to break for food, photography and rest stops.

Definition of terms

The terms used in this guide are intended to be as unambiguous as possible. In walk descriptions, ‘track’ denotes any thoroughfare wide enough to permit vehicle access, and ‘path’ is used to describe any that is wide enough only for pedestrians and animals.

You’ll see references in many walks to ‘GR’ and ‘PR’. GR stands for Gran Recorrido or long-distance footpath; these routes are marked with red and white waymarking. PR stands for Pequeño Recorrido or short distance footpath and these routes are marked with yellow and white waymarking.

The Gibraltar ridgeline seen from the Mediterranean Steps (Walk 10)

GPS tracks

The GPX trail files for all of the walks featured in this guide are available as free downloads from Cicerone (www.cicerone.co.uk/803/gpx) and via the author’s website (www.guyhunterwatts.com). On both websites simply request the GPX files for the book via the Contact page.

By using a programme such as Garmin’s BaseCamp you can download the files to your desktop, import them into the programme and then transfer them to your handheld device. You can download Basecamp for Mac and PC at www.garmin.com/garmin/cms/us/onthetrail/basecamp.

GPX files are provided in good faith, but neither the author nor Cicerone can accept responsibility for their accuracy. Your first point of reference should always be the walking notes themselves.

The path leading up to the Pico de Mijas (Costa del Sol, Walk 22)