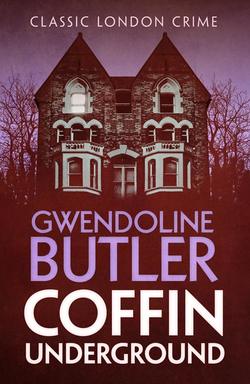

Читать книгу Coffin Underground - Gwendoline Butler - Страница 7

Chapter One

ОглавлениеThe house stood by the church and by the church was the churchyard which the house had done its share to fill. More than its share, in truth.

There was already another body about to take up residence but no one knew about that yet.

The past, of course, was different.

In the last century, when the house in Greenwich was only a few years old, a visitor from abroad had brought cholera with him from India, which had spread through the district after killing him. A lot of new graves appeared in St Luke’s churchyard at this time.

Nor had the house, No. 22, Church Row, ceased in its work of filling graves. In addition to what you might call the average statistical supply of family bodies, inhabitants of the house, dying in the usual way from old age, childbirth or the poor medicine of the period, the house picked up other victims. It attracted the blast from a bomb dropped by a Zeppelin in World War One and from a landmine in the second great war. Neither was a direct hit, but each time there were many casualties in the house, which seemed to fill up for the occasion of a calamity as if it knew one was coming and wanted to do its best. Or worst. In 1917 when the Zeppelin hung over Greenwich the house was crowded with a party of young soldiers, home from the trenches and celebrating the twenty-first birthday of the son of the house. As it turned out he would have been safer in the trenches. (His twin sister survived the blast but the house got her in the end, because she died, with her parents and younger sister, in the great influenza epidemic of 1918.) In 1941 the house was used as a hostel for nurses working in the nearby Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, the owner being abroad on war service and his wife and family evacuated. Most of the nurses were killed, and of those that died, some, being local girls, were interred in one great grave in St Luke’s.

A quiet time set in for No. 22, Church Row after the war. It had had enough. Or it was resting.

In 1972 the then owner of the house, a career diplomat, was abroad with his family (he came back the next year, and then in 1975 left for New York), and the house was let to three students in the University of London, who were enrolled in Goldsmiths’ College at New Cross. They were quiet, unobtrusive lads, not much seen and no trouble to anyone.

Since the other inhabitants of the street did not see them regularly, they were not at first much missed. No one saw them come in, no one saw them go.

But they did go somewhere because they were never seen alive again, leaving a lot of blood behind in the house. Blood on the stairs and in the kitchen on the ground floor. So it was told.

In 1978 a policeman called John Coffin, now a Chief Superintendent, moved into Church Row, and heard all the stories about the house and treated the superstition with the contempt it deserved.

He was able to do so, of course, since he was not living at No. 22 (although he knew the present owners) but at No. 5, well away from any dangerous emanations.

It was Mrs Brocklebank, who cleaned his house and also did for No. 22, who told him the saga. She could even add to the story, and did, the moment she saw her chance.

‘Oh, come on now, Mrs B. It’s all rubbish. Houses can’t do that sort of thing. You mustn’t be superstitious. And as for the students, was there really any blood? I heard they just moonlighted, left without paying their rent.’

‘Never been seen again, though, have they?’

‘Well, I don’t know about that.’ He did not know the details of the case, if indeed there had been one. He seemed to remember there was some puzzle about the three students. Or was it just one of them?

But for Mrs Brocklebank the blood was an indelible part of the story. Literally so.

‘Every time I clean that house on the anniversary of the disappearance there is blood on the front step. I have to scrub it away.’

‘Oh, Mrs B.’

‘Never really get it off. It’s always there. Faintly. But worse on that day.’

‘Did you see the blood in the house yourself, then?’

‘Well, no. Wasn’t working for Mrs Pitt then, was I? In the soap factory, Deller’s, I was, before I decided to better myself. But we all heard. Everyone knew about it.’

She admired her new employer. You’d never know he was a policeman, she told herself.

He was a tall man, thinner than he had been, thinner perhaps than nature intended, a long face with fair hair just beginning to show traces of grey. He had never been good-looking but experience, life itself, had drawn on his face the lines which gave him distinction. His eyes still had the hopeful look which had been his as a boy. If you did not have hope in the world of London streets in which he had grown up, you had nothing, and never would have. It was this look which had drawn Mrs Brocklebank to tell him about the blood. Tell him, she’d advised herself. Get if off your chest.

Coffin deliberately went to take a look at the step of No. 22 one day, and it was true there was a string of faint stains that could have been blood on the two shallow stone steps to the front door. But they could have been a lot of other things as well.

No. 22 was a quiet dark house of three storeys, possibly a shade gloomy but otherwise unremarkable, and identical to the house where he had recently moved into the top flat.

Nothing in it, all rubbish, he thought. Just a house that has got a bad name. And he thought of all the other such houses there were. Blythswood Square; Rillington Place; The Priory, Balham.

But he was interested enough to make some inquiries about the case of the missing students.

His opportunity came when he had to deal with a local sergeant about another case. A violent criminal, William Howard Egan, had just come out of prison after serving his term and was known to be looking for revenge on the informer who had helped to put him there. The fact that this informer was his son-in-law, Terence Place, was not going to stop him. Both hunter and hunted were believed to be hiding in South London, and they might be in Greenwich. John Coffin had been the detective on the case. Threats had been made against him too by Egan. He was taking a personal interest.

‘I don’t think Billy Egan’s here, but that isn’t to say he won’t be, or isn’t, he was always a cunning bastard. He has a taste for this part of the world, so he might be back. I’ll keep my eyes open. You can count on me.’

‘Thanks, Bernard.’ Coffin took his chance. ‘What’s this tale I hear about three students going missing from a house in Church Row? Anything in it?’ He remembered a bit himself, but not the details.

The sergeant was an older man, passed over for promotion, but content to be what he was, and a great well of information about the district, which he transmitted only when it suited him, it was his property. He had lived in this part of South London all his life. Bernard Jones had known John Coffin when he was a humble detective, well before he had shot up the ladder so successfully. He was far too tactful to dwell on this, or even to mention it. It coloured their relationship, though, loading it with memories of old cases, old criminals and older colleagues.

The two men were having a sandwich and a cup of tea in the police canteen in Royal Hill police station where Jones was based. He didn’t want to talk about students, missing or not, he wanted a gossip.

About crime in his patch.

‘Been fairly quiet here lately. Two bodies found roped together in the river. Black man, white woman. The forensics say it could be suicide. Old man found dead in the street. Been dead over a week when found on a main road. Can you beat it? I suppose they thought he was put out for the dustmen. Two dead babies in a suitcase. No, nothing special.’

Or gossip about old friends.

‘So Dander slipped off the side.’

‘Yes.’ Coffin looked serious. Commander Dander had been his patron and friend. ‘And I didn’t even know he was ill till he went. Very sudden. Heart. Still, it wasn’t a bad way to go.’

‘What he would have wanted.’

‘Don’t know about that.’ Coffin remembered his Dander. ‘If he’d had what he wanted, I think he would have lived for ever.’

‘Hard on his wife, though.’

‘Which? Dying suddenly or living for ever?’

‘With Charley Dander I should think living for ever would be the worst punishment.’

‘Did you know he had three wives?’ said Coffin. ‘We none of us knew till they all turned up at the funeral. All divorced and all hating the sight of each other.’

‘I bet they were lookers. Dander knew how to pick them.’

And leave them, thought Coffin, a man loyal to his mates but not to his women.

‘I hear you’re living in Church Row?’

Coffin nodded.

‘Nice houses, but a bit near the churchyard for my taste.’ So the sergeant, who knew everything, had heard the tales about the powers of No. 22.

‘I’m the other end.’

‘Just as well.’

‘So I’ve heard.’

The sergeant laughed.

Coffin tried once more: ‘What’s this tale about three students disappearing from a house in the Row, leaving a lot of blood behind and never being seen again?’

The sergeant sighed. ‘That old tale going round again? They didn’t disappear. Or not for long. There was a bit of blood about, though. What happened was, the three of them had a fight, got a lot of blood on the furnishings and lost their nerve about the damage they’d done. I think they did drop out of sight for a few days, but not more. The College soon got on to them.’

‘I’m beginning to remember some of the details myself now. It’s coming back. There was something later about one of the students, though, wasn’t there?’

Bernard Jones picked up his sandwich, inspecting it. ‘They put less and less ham in these every day, I say. But they say they don’t. More if anything. One day I’ll measure.’

‘Yes, that’s the scientific approach.’

The sergeant ate the sandwich in three great mouthfuls, talking between bites. ‘Something about one of the students, Malcolm Kincaid. He was a chemistry student. A year after he graduated he was found dead in Greenwich Park. His body was lying tucked away in some bushes. Killed himself. Left a note saying he was going to do it. He did it with cyanide, he’d managed to lift a quantity from the lab where he was working. It’s a quick death. The medical evidence was that he died almost instantaneously.’

‘So what?’ It was obvious there was something.

‘Nothing to show how he’d taken it, no container, no poison, although he’d stolen a good five grams. In the form of potassium cyanide which would have gone down better if dissolved in liquid. Caused a lot of worry, that did.’

‘But he left a note saying he was going to kill himself?’

‘Oh yes, it was there with him. And he had the motive. That came out: girl trouble and money worries. He was a bit of a depressive too. Yes, he meant to do it.’

‘So what was the worry?’

‘Looked as though someone else had been there. He was all neat and tidied up. When you take cyanide you don’t die that way.’

Coffin thought about it. ‘Interesting. What happened then?’

Bernard shrugged. ‘A verdict of suicide was reluctantly arrived at.’

‘When was this?’

Bernard worked it out. ‘About three years ago. Just over.’

‘One of life’s little mysteries,’ said Coffin.

Then the talk turned to other things, and he buried the story of Malcolm Kincaid, student, at the back of his mind.

One of those puzzles you think about in the middle of the night and can never decide on an answer. It could go in the drawer with Mr Qualtrough of Men-love Gardens East, and where was the axe that killed the Bordens?

He thought a bit about William Egan the grudge-bearer, and kept on his guard, but there was no sign of him. Nor any movement in the undergrowth of the local criminal jungle that might show his passage. Once or twice he thought he saw Mrs Brocklebank, that conveyor of news around the town, giving him a thoughtful look as if she knew something he did not, but that probably meant nothing more than that she was news-gathering.

He liked the new flat in Church Row, where over the roofs and through the trees he could see the top of the clipper, the Cutty Sark. At the moment the trees blocked his view, but in winter when the leaves had thinned he would be able to see the intricate rigging of the ship. He liked that thought. Living here was bringing him back to an area he had known as a boy and where he had worked at the beginning of his career. It was a part of London for which he retained an affection. For ten years he had been living away from the suburb, he had moved off deliberately, there were mixed memories, some good and just a few downright painful, but now he was glad to be back. It felt like home. It was amazing how life stitched itself together again into a piece if you gave it a chance.

Every time he walked down Church Row on the way to work, he took a look at No. 22. It had been empty for some months since the last tenants had left. Then one day he saw the windows had been washed and plants put in the window-boxes. It was spring, they were daffodils. Yes, said Mrs B., the owner and his family are coming back. Edward Pitt had retired from the FO; he had been working at the United Nations. John Coffin was looking forward to meeting him again, a friendly, vital man, as he recalled. The whole family was interesting. People said they were artistic and amusing. They had a few critics too, but that was understandable. There had been ‘family’ problems, whatever that meant, but even the easiest of families did not always see eye to eye. Interesting to watch how they got on in No. 22, where by all accounts they had never lived much. He might find out what they knew of the story of the three students. He looked down at the front steps. No real sign of blood.

Blood.

He had got his life settled: he had got someone reliable to clean his place in Mrs Brocklebank, who, he now realized, ‘did’ for most of the road, and who had really acquired him rather than the other way round; and he had arranged for two newspapers to be delivered daily, and had settled on a milkman who also sold bread and eggs. You could live on bread, milk and eggs if you had to. Everything was in train. The only drawback was that Mrs Brocklebank would not iron his shirts. Or anything of his.

‘I do Brock’s and that’s my lot.’ It was the first time he had realized there was a living Mr Brocklebank; he had supposed her to be a widow. She had the vigorous healthy look of a woman who lived for herself alone.

He tried drip-drying his shirts himself, but he liked the cuffs ironed. He tried ironing them himself. It was easy if you didn’t scorch them. He did scorch them. Quite often. Too often.

He sought help.

Mrs Brocklebank surveyed the burnt offerings without sympathy. ‘It’s quite simple if you keep the heat on the iron adjusted.’

‘I do keep it adjusted. But it leaps up.’

‘I’m not a laundress myself.’ She considered; Coffin waited hopefully. ‘I suppose you could try Sarah Fleming. Sal has a good hand with the iron, she ought to have with the practice she gets looking after that brood of hers, and she’s usually glad to earn an extra pound or two.’

He left the arrangements to her, with the result that she took away his washing on a Monday and it reappeared, neatly packaged and with the bill, on his doormat every Wednesday. Mrs Brocklebank acted as banker.

Occasionally messages came back through Mrs B.

‘Sal says you need a new blue shirt. The cuffs are frayed and it’s not worth the trouble of ironing.’

Sal obviously had high standards. He bought a couple of new blue shirts.

‘Sal says could you try not to get lipstick on your collar.’ This message was delivered with a slight smirk. ‘She says it’s hard to get off.’

‘It’s red ink,’ said Coffin, lying.

Living as a bachelor, and at the moment wifeless, he was not celibate. But he felt it was his business and not Sarah Fleming’s. Sal, he decided, could look after her own affairs, if she had any apart from laundry, and leave his alone. Old witch.

Two weeks had passed. There was no news of either William Egan or his son-in-law but the daughter had taken herself off to Spain. It might mean something, or it might mean no more than that she had had enough of both father and husband. The general feeling was that she had a right to such a reaction.

But the Pitts had arrived home and No. 22 was looking lively. Windows opened to let the sun in, new curtains and a big car parked outside the door. John Coffin had not met them again yet, but had seen them once or twice as he passed and given a wave. Whether he was remembered or not he was unsure, but diplomacy and good manners prevailed, so that he got a wave back. Edward Pitt was tall and handsome, every bit the diplomat. With white hair he looked older than he probably was, just as his wife looked younger. Irene Pitt was still youthful, a pretty, curly-haired woman with bright eyes and skin with a shine on it. But the beauty of the family was the daughter, a slender, leggy creature of fifteen years. She had joined a smart London girls’ school and disappeared on the train every day to her studies. There was a younger boy who had been recruited to the local public school, and heaven help him there, said Mrs Brocklebank. She added the information that Mr Pitt, although retired from the Foreign Service, was going to join the foreign bureau of a London newspaper, and that Mrs Pitt, who was an economist, intended to find some work too. She was a lot younger than her husband. There were also a dog and a cat to join the household but they were at present in quarantine.

That concluded her head count, but she added the news that the Pitts would be giving a party for friends and neighbours to celebrate their return.

Nothing was said about the bad character of the house, but Coffin felt it hung there like a grim smile on the face of a friend.

No sign anywhere of William Egan, but his son-in-law had been spotted once down by the river. He had got on a bus and disappeared in the direction of Woolwich before he could be stopped.

The contact who claimed to have seen him, a GBH man of many violent episodes and many incarcerations, now going straight, said he was just standing by the river staring at the Cutty Sark.

Thanks,’ said Coffin over the telephone to Bernard Jones. ‘I’ll keep my eyes open for him myself. I think I know his face. Red hair with a matching moustache on Place, as I remember, and a bit of a bent nose.’

‘You’ve got the man. And it was his wife who bent the nose. With her handbag. Like father, like daughter.’

Bernard Jones was his hot line to what was happening inside Greenwich; it was always useful to have one, especially as he himself had more than one case on his hands. Crime was really bubbling in South London.

His career was at an interesting point. He had recently been appointed to head a small group of detectives based in South London and charged with the overall investigation of all serious crimes in the area. The Tactical Activity Squad it was called, known as TAS. It was a period when such bodies bearing impressive initials were appearing on all sides. He and TAS were a part of the times. He was assisted by a chief inspector, who was his deputy, and by a very young and sharp inspector, and by three even younger detective-sergeants. He found himself relying more and more on Inspector Paul Lane. The authority of TAS overrode the local CID structure, which had lately been the subject of an inquiry. He was well aware that he and his team were not popular and that to see him rubbed out by a man of known violence would cause very few tears.

‘Thanks, Bernard. What about a drink at the Painted Parrot at the weekend?’ An arrangement was made. It was Wednesday and he was home early for once.

He went to look out of his window. Not very likely that either Egan or his son-in-law, Terry Place, would be walking down Church Row, but you never knew. His luck might be in.

Round the corner from Queen Charlotte’s Alley came a girl, tall and slender, with bright auburn hair tied in a ponytail with a white bow; she was pushing a pram and was accompanied by a young boy who was holding her hand. He was hanging on to the skirt of a small girl. Behind them came a youth, also red of hair, clearly related, carrying a bundle.

There was something about that bundle that looked familiar to John Coffin.

The whole procession came to a stop outside No. 5. Then the lad approached the house, and he heard the bounding of feet up the stairs and the noise of something bouncing against his front door.

He counted up to ten, then went to look.

Yes, his washing. The girl pushing the pram was Sarah Fleming. She had a bright, clever face, with the promise of beauty, she looked about sixteen, but was no doubt older. Her clothes were simple, jeans and a shirt, but she wore them with style, yes, that was it, she had style.

And if the rest of the bunch, the little ones, were not her own offspring, then they were her brothers and sisters.

Queen Charlotte’s Alley was a short cul-de-sac bounded at the end by Deller’s soap factory. Deller’s no longer made soap on the premises; thus the air was not so noisome as previously, but it was still a working concern with heavy lorries rumbling in and out of the yard all day. Queen Charlotte’s Alley was not a quiet street, and never had been throughout its two hundred years of life, because the little workmen’s cottages had housed the large families of the times, many of whom had worked in the foundry which had stood on the site where Deller’s was built. In those days there had been access straight through from the alley.

Now there was only one large family in the street and that was the Flemings. The other houses, and there were but six, were nearly all occupied by young couples who liked to say they had bought an eighteenth-century house in Greenwich and were renovating it. Which usually meant putting in a new kitchen and a bathroom and brass fittings on the front door. There were a couple of elderly survivors from the old days, living on in their unreconstructed cottages. The Fleming family belonged in this party since the house had been rented by the family for at least three generations. To their despairing landlord they seemed like sitting tenants in perpetuity.

‘I don’t like you doing his washing.’

‘Oh fiddle. The money’s good.’ She was more or less working her way through the Polytechnic A-levels course, with a firm eye on Oxford. She was bright and knew it. ‘Old Brocklebank did us a good turn. Besides, I only take it down the laundrette, and then iron it. He could do it himself if he thought about it.’ From John Coffin she had earned enough money to buy two books she badly wanted: she created a kind of study for herself in a corner of the kitchen, with a table and bookshelves where she could work in peace. Like everything Sal did, it had a kind of imaginative elegance.

Now she was setting the table for a meal, moving briskly about. A kettle was humming on the old gas stove with a big brown teapot hung over the spout to get warm. In a little while there was toast on the table, a pot of jam, and a row of six cups to fill.

‘Call the kids.’

‘We’re here waiting, Sal,’ said a soft small voice.

‘Yes, you are, Weenie, but not the others.’

Weenie was the little girl whose skirt had been so firmly grasped. Food was Weenie’s delight, she was always hungry.

‘They’re under the table, Sal.’

Weenie lifted the cloth to reveal her three brothers crouched there. Their ages went up in steps. Then there was a big gap until Sal and her sibling, Peter. Mr Fleming had been away at sea for a good spell after their births, then he came back and the family progression started again. Mrs Fleming never seemed to get the hang of birth control, to Sal’s fury. Even in those days, she had known what would be best for the family. Less of them, far less. Preferably just her and Peter.

At the table, watching them eat, she felt this even more strongly. They were a responsibility.

‘You certainly eat well, Weenie, but you don’t grow on it.’

Something had gone wrong with the genes, she felt, when it came to Weenie and the others. She and Peter were all right. She knew herself to be clever and there were times when she felt beautiful, and Peter was certainly good to look at and he was very practical if not scholastically inclined. But the others, well, it was hard to be sure, she was watching them and trying to make up her mind. Not like me, she felt.

She knew she was doing what was right, but she didn’t have to like it. The little ones could go into care, the social worker had said when their parents died, but Sarah had turned this down. It wasn’t that she loved them so much, probably she didn’t, but she had the feeling that there was something strange and secret about them as a family that was better kept private. So a special arrangement had been made with the social services.

‘Give me some money,’ she had said, ‘we’ve got the house. We’ll manage, thank you.’

They were a burden she had hoisted on her own back and it was heavy there.

Weenie, Tom, Lester, and Eddy.

‘Where have you boys been putting your feet? Black marks all over the carpet,’ she said, then pressed on without waiting for an answer. ‘Your turn tomorrow,’ she said to Peter. ‘I’m at the Poly.’

She had had to leave school before her A-levels, but she was continuing her studies at the Local Polytechnic College. It was her intention to get a place at Oxford. Balliol, she believed, would suit her as it seemed a radical place. She was left-wing in her politics.

He grunted assent; he never argued with her.

‘The Pitts are back,’ he said. By which he meant he would rather be with them than her, wanted to be invited by them and hadn’t been.

‘I noticed.’

‘Nona’s home.’ But he hadn’t seen her. That was what he meant.

‘Three years is a long time, Pete.’ A long time for a girl like Nona; she had been twelve when the two had been inseparable and Peter only fifteen. Now she was fifteen, nearly sixteen. She would have changed. Sal knew how a girl could change. Especially a girl with Nona’s background. But Peter had not changed. People like Peter don’t. They become what they have it in them to become at an early age and stay that way. Possibly for ever.

‘You couldn’t expect things to be the same.’

‘It was her mother’s fault. I blame her. Everyone knows she was having an affair with that MP. And because Mr Pitt was angry he took it out on me.’

It hadn’t been the way it was, and she thought he knew it, but she could sympathize with his anger. Compared with the Pitts, what did he have?

‘Nona was only a kid,’ was all she said.

He was silent. Then he said: ‘That chap you’re doing the washing for is a policeman.’

‘I know.’

It was the only thing she had against him.

John Coffin, policeman, was not someone she wanted to work for. Why couldn’t he be a dustman or a bank clerk?

There was a telephone call for John Coffin when he got home from work that night. He was early, for once, and the telephone sounded within minutes of his arrival, as if it had been ringing at intervals hoping to get him.

‘John? Bernard here.’ The sergeant’s voice was urgent. ‘There’s been a body found. You’ll hear about this through channels, but I’m telling you now. I don’t know how you’ll get the message but take it seriously. If I were you I’d get down there now and see what they’ve got. Go through the Wolsey Road entrance to the Park.’ And he rang off.

A green and wooded hill stretches down Greenwich Park towards the river. The ground is uneven with many little dips and hollows. The body of Malcolm Kincaid, the suicide, had been found in one such. John Coffin had walked home that way after parking his car in the garage he rented. He enjoyed the walk but felt alone on it, undressed. Every other walker seemed to have either a dog or a child. Perhaps he might get a dog. Except for his sister Lætitia, his life was empty of close personal relations at the moment. Lætitia, a long-lost sister who had come back into his life some years ago, was a joy. But she was rarely in the same country he was or indeed in any country for long. As well as a rich and itinerant husband, she had a successful career as a lawyer which seemed to involve a great deal of travelling.

There was their other sibling, of course, related by half blood through their mother to them both. But at the moment he or she was more hypothetical than real because they had not managed to track him down. Or her. It was strange to think that his mother had given birth to yet another child about whom he had known hardly anything until Lætitia had told him. But she had their mother’s word for it. ‘Born between you and me and given for adoption,’ Lætitia had said.

Their mother seemed to shed children like lost parcels.

As he walked down the hill towards Church Row he had seen a police car speeding up the hill. Trouble somewhere, he had thought, dragging his feet free from a patch of wet tarmac that lay across the pavement. Now he knew what it meant and where to go.

In through the gate, along the path towards the chestnut walk, always the ground rising. A small crowd of people standing watching from a distance, barriers being put into position and the whole area corded off.

Yes, he was here in good time.

He was known; his rank and his position smoothed the way.

Among the trees was a thicket of shrubs with a small path which led to a tiny brick pavilion with a bench in it.

Crouching against the bench as if he was praying was the figure of a man. His back was towards Coffin.

He walked right up to him and stared in the dead face. Eyes open, mouth twisted.

‘Good Lord.’ Not the face he had expected.

‘Know him, sir, do you?’

Oh yes, I know him, and you know I know him.

‘It’s Billy Egan.’ William Howard Egan, who had come out of prison eager to revenge himself on those who put him there. His son-in-law first and then John Coffin. Or possibly the other way round; on that point one had never been quite sure.

And now he was dead himself. Only a few weeks out of prison and murdered.

He looked as though he had been garrotted: there was blood in his mouth and coming out of his ears. Even bloody tears around his eyes.

But in addition, he had been stabbed many times. Cut and slashed as by a madman.

‘I suppose we ought to start looking for Terry Place,’ said Coffin.

On his way home he saw that the steps of No. 22 had been newly washed. Mrs Brocklebank at it again, he thought.