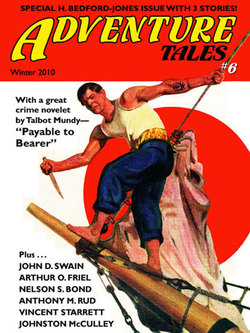

Читать книгу Adventure Tales 6 - H. Bedford-Jones - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMUSTERED OUT, by H. Bedford-Jones

I.

Sergeant Aloysius Larrigan inspected the houses ahead—and hesitated. Before he found name and wealth and fame in California film fields, Aloysius Larrigan had been born and raised in New York. Hence, he knew the metropolis. He knew that behind him on Fifth Avenue were the false jewels; and that here ahead of him was the real thing. Here, half a block off Fifth Avenue, was the house of Jim Bleeker, bunky of Sergeant Aloysius Larrigan.

But the sergeant hesitated, gripping the package a little harder in his hand. Then, mustering up courage, he approached the doorway and rang.

The outer door opened, and a stolid butler gazed at him.

“I—I’ve come to see Mrs. Bleeker,” said the sergeant nervously.

“It’s quite early, sir,” answered the butler, somehow stifling his first instinct of blank rejection. “I hardly think, sir, that Mrs. Bleeker is—”

“Look here!” snapped Larrigan, flushing. “I’ve just landed from France. My name is Larrigan. Jim Bleeker was my bunky—”

“If you’ll step inside, sir,” hastened the butler, changing countenance abruptly. “I’m sure that Mrs. Bleeker will wish to see you.”

Aloysius Larrigan sat himself down between a mounted piece of fifteenth-century armor and a dull-gleaming Rubens. All this, he knew, was the real thing. He had guessed that Jim Bleeker was an aristocrat; but—well, all this was a bit crushing. Before he quite realized it, Mrs. Bleeker, in her widow’s black, was upon him and holding his hand.

“Jim wrote me so much of you!” she was saying quietly. “I’m very, very glad to know you, Mr. Larrigan. I received your letter from Bordeaux, telling me of the final days—I cannot tell you how I appreciated the sweetness of that letter.”

Aloysius Larrigan blushed fearfully. He stammered something and fell silent.

“You must stay for luncheon—but how long shall you have in the city?”

“No time at all, ma’am,” returned Aloysius. He displayed his package. “We’re going through town to be mustered out, and then I have to hit for California. I’ve got important business there, you see—a lady I’ve not seen for a year, and also business. I just got permission to run up here with this.”

He thrust forward the package, all his carefully rehearsed speech and actions gone to the winds.

“You see, Mrs. Bleeker, Jim made me promise to bring these things here myself. They are just the little things; well, you’ll see. He thought maybe you would like to have them. I have to be back in half an hour.”

Mrs. Bleeker took the package, bit her lip very hard, and then threw back her shoulders and looked Aloysius Larrigan in the eye. He realized that hers was a peculiar bravery—the courage of deep things, of rare blood, of a sensitive, inner grief that was tearing her very soul before his eyes.

He felt tongue-tied and extremely uncomfortable, far different from the easy assurance habitual to him.

“Wait just a minute, please,” she said, and left him.

He waited, gazing at the velvet hangings, the deep softness of everything around him, feeling himself frightfully out of place. The knowledge that he was an American soldier, and as good as any man alive, did not help him.

Then he smiled grimly at the thought of how little the studio directors knew about the furnishings of an aristocratic home! All the studio men knew about was the flashy emptiness of the newly rich and the professional decorator.

Mrs. Bleeker was before him again.

“I’m more sorry than I can tell you, Mr. Larrigan, that you have to run away so quickly. When you get settled in California, will you please send me your address? One does not know what unforeseen emergencies may arise.”

Aloysius promised.

Mrs. Bleeker produced a little morocco case.

“I would like you to have this,” she said quietly, very steadily. “I brought it to Jim once; he always wore it. There’s no other man I could give it to, Mr. Larrigan—but if you would accept it, you would give me great pleasure.”

Larrigan gazed at the scarf-pin, an abalone blister mounted in gold.

It came to him that this was a very precious tribute, a tribute from the woman’s heart, meaning more than words could say.

Jim Bleeker had other friends, of course—wealthy friends, college friends, all that a man of his standing would have. But he, Larrigan, had been Bleeker’s bunky in France, had watched Jim Bleeker die, had been more to Jim Bleeker than any man alive.

And this was a tribute, the most precious heart-gift he would ever know.

“I—I’d be very glad,” he said, stumbling over the words, cursing himself because he could not express the thing that was in him, the feeling that gripped him in that moment of revelation. “ I’ll be wearing cits in a couple of days. I—I sure appreciate this very deeply, Mrs. Bleeker.”

“There’s no other man I could give it to,” she said again very softly.

This was all. He was thankful that his face seemed quite unknown to her.

II.

Reever Keene was home again—Reever Keene, the great; Reever Keene, the man who had snapped asunder his fabulous contract a year ago in order to enlist as a private; Reever Keene, whose pictures were the greatest drawing-card in every theater of the country!

He had sent no notice of his coming, but the studio knew of it and was ready. As the Overland drew in, sixteen automobiles were waiting, and these automobiles were the cream of motion-picture motordom. All Los Angeles knew that the aluminum car with purple trimmings was Reever Keene’s; that his director owned the pea-green Twin Duplex striped with canary; that his leading lady had paid eleven thousand dollars for the screaming blue-and-gold roadster, and so forth.

But a terrible thing happened at the station—a thing which, fortunately, was kept out of the papers by influence. As one of the lesser lights of filmdom grasped the hand of the great Keene he gave a raucous laugh.

“For Heaven’s sake, Reever! Where’d you get the abalone sparkler? Wow! Look at it, folks; pipe the—”

Reever Keene’s fist smashed him square in the mouth.

The press-agent wanted to use the story, of course; but Reever Keene took the press-agent by the nape of the neck and kicked him hard. Influence did the rest—advertising influence. The story was killed.

“I can’t understand what’s got into Keene,” said the director, riding back to the studios with the president of the company. “And look at the face of him! We’ll have to paint him an inch deep to disguise that brick-red tan and make him come out like the old screen idol! Fortunately his profile is all right still.”

The president grunted. He was a wise man, or he would not have been in his present position.

“Keene takes up his contract where he left off,” he returned. “That’s all I’m worrying about! Let Keene run the whole damned place if he wants. If you’d gone into the army, my son, instead of sitting on your draft-proof job, the Lord knows you’d be a damned sight better director!”

The director looked at his leather puttees and said no more.

“Where’s Lola?” asked Reever Keene, driving to the studios in his own car once more, his leading lady and chief supports gathered around him. “Thought she might be around?”

“She’ll turn up at the studios,” was the response. “Working on a location near Santa Monica to-day. They’ll be back for dinner. We’re having a real celebration, old boy!”

“Lola’s awful proud of that sparkler you gave her,” simpered the leading lady. “Heaven knows it was a beaut!”

Reever Keene shivered a little. He was not sure why he shivered; nor was he sure why the warmth and cordiality of his reception at the studio left him cold and hard.

He had not thought it would be this way. He had looked forward to falling right back into the old rut, among the old friends, and he had anticipated swaggering like a good one—all kinds of publicity in it! But, somehow, he found himself landing with a horrible jar. He was damned glad, he reflected, to be done with the bare simplicity of the soldier’s life, with the saluting and uniforms and general prophylaxis; and yet—

Homesickness had glamoured all the old life, but now that he was back in it, the glamour seemed unaccountably like tinsel. The directors, for instance, even his own director and old crony, with their puttees and riding-breeches, general superiority, and bustling business—well, maybe it was the puttees that grated. Keene had saluted leather puttees until he was heartily sick of it; but that was another story altogether.

He wondered inwardly if he had ever been like the men now around him—good fellows, of course, but abominably artificial. These fancy tailored garments, these amber cigarette-holders and sodden cigarettes without a bite, these flashing jewels, and, worst of all, this breezy talk that moved in perpetual high lights—

What the devil was the matter with him, anyhow? Maybe it was because Lola had not come yet.

Well, Lola came, with a stifled shriek and a tiny Peke, and flung herself at him. Good Heaven! Keene had been away from studio paint so long that her appearance frightened him. And had he really picked that engagement ring, that diamond like a walnut? Yes. He remembered hideously the glee with which he had nonchalantly signed that five-thousand-dollar check, and the delight with which he had seen the check pictured in the papers.

“You’ve been away a hell of a long time, old sport!” and his director clapped him on the back. “But now you’re back to the life—the only life, boy!”

“Right you are!” cried Reever Keene, bracing his shoulders. “Let’s have a drink!”

III.

The fact that Reever Keene, home from the army, insisted on working with an abalone blister in his scarf, was an idiosyncrasy good for three-day comment in the press. And the press-agent sighed for the lost opportunities that were closed to him simply by the stubborn deviltry of Keene. Nobody knew what had got into the screen star. He had changed. The abalone pin, for instance, was a sore subject with him.

He never wore any of his former loud attire, and had discarded all his jewelry, which formerly flashed in the cabaret lights of Los. He even wore that abalone pin stuck in the front of his dress shirt, for a society picture; and when the director expostulated, Keene bluntly told him to go to hell—which was no way to treat a famous director.

Then somebody in the scenario department—that is, somebody in the orange-hued flivver class—had an inspiration. He wrote a story about that abalone pin. Keene, according to his contract, had the say about what film stories were to be accepted for his use; and he went into closed session with the scenario department, and there was evolved a scenario which made the director gasp. But the scenario went through; it had to go through, with Keene backing it.

“What’s come over him?” said the president to the director. “He used to get stories written by his friends, turn down everything from the department, make us pay five hundred dollars for the stories—and then split with his friends. That’s the old stall; what’s this new wrinkle?”

“Damned if I know,” groaned the director. “It’s got society stuff in it, and only last week he said he’d never touch society stuff again. And there ain’t any punch, not a bit; it’s one o’ them bleedin’-heart things, and it ain’t got—”

“It’s got Reever Keene in it,” snapped the president, “and that’s enough to put it across anywhere. Do you get me?”

The director departed, weeping.

Worse was to come, however. Reever Keene sold his gorgeous car, and showed up with a plain green-black affair—not even a victoria top to it! Lola refused to ride in the wretched thing, and Keene swore; and the end of this matter was a fine quarrel which the press-agent featured without the least opposition.

And then came the first of the month and the new story.

The story was a society story, right enough. For three days. the company was on location at the Billingkamp residence—you remember, of course, Billingkamp’s Canned Soups—and the exteriors were gorgeous affairs.

The trouble was that Reever Keene had been reading some highbrow stuff, and insisted on wearing his silk hat without any of the rakish tilt which is so fetching to the screen folk; and he insisted on throwing out the beautiful white roadster with red upholstery which the director had provided, and used his own sobersides of a car—and other things like that.

In between times the quarrel with Lola was deftly adjusted, the date was set for the wedding, and duly featured by the press-agent.

After that the company came back to the studio, the remainder of the picture being interior sets—and then the trouble really began. Reever Keene had instructed the property-men about the drawing-room set; the director had done likewise. Props, seeing himself between the devil and the deep sea, provided both sets, and left the principals to scrap it out. Which was wise.

Reever Keene took one look at the director’s set, and ordered it off the stage. The director was inspecting Reever Keene’s set, and Keene met him in the act.

“My Lord!” said the director. “I don’t know anything about motion-pictures; I’m just a poor simp who’s spent all his life in the game. Look—for the love of Heaven, look!”

“Get down to cases, you,” growled Keene. “Never mind the high-art stuff, now. Just be sensible and tell me what’s wrong!

The director swallowed hard and waved his hand at the set. It had been assembled with a good deal of trouble. There was an imitation Rubens; there was a real set of imitation armor that looked from the camera considerably like fifteenth century. The rest was deeply rich velvet and hangings.

“As man to, man,” said the director, “I’ll put it to you, Keene. How do you think this dark stuff is going to take? All to the bad! It can’t be done, man! You’ve got to have contrast. Now, can’t you realize that this picture has got to show a society home? A real swell home. None of your junk, but stuff that spells money. They eat it, the people do!”

“If you knew the money we’d spent on this set,” began the property-man plaintively. But Keene interrupted.

“What would you suggest, then?”

“Just what I ordered set up!” returned the director. “Statuary. A nude on the wall. Some o’ this here lacquered Chinese furniture—we got Bent’s whole store to draw on, and you know the best people ain’t buying anything else but lacquered, which shows up like real money. Then that high-colored rug, and so forth. It’ll be toned down fine in the film, Keene.”

“Maybe so, maybe so,” said Reever Keene.

“And then these here costumes. I been reading over your directions.” The director tapped the papers in his hand, with growing boldness. “I notice you got white neckties with evening clothes; you know’s well as I do they don’t make contrast. Then you got the society dames ordered to cut out the low-neck stuff—What the hell gives you such a notion of society, anyhow? Don’t you know they run around half naked? And no jewels. My Lord! If I was to run out such a picture the society papers would give me plain hell!”

“If you had ever read them at all,” said Keene dryly, “you’d see they do that, anyhow.”

A few minutes later the president sent for Reever Keene.

“Take a cigar, Reever,” he said genially. “Now, we’ll have to cut out this fussing between you and Bob, see? He’s a damned good director; I’m not paying him twenty-five thousand dollars for nothing.”

“Let him mind his own business, then,” said Keene, a little white around the jaw. “I’ve got a good picture, and he’s not to spoil it.”

“Sure not,” agreed the president affably. “But see here, now. He’s contracted to put out your pictures, ain’t he? All right. And he’s got the say.”

“In other words,” said Keene slowly, “I’ll have to stand for his directing in this picture, eh?”

“Sure. His contract is up in three months. If you want, I’ll put you in charge of your own directing after that.”

“Then stop work on this picture until he’s out of it.”

“Can’t do it; Reeve—we’re a week behind on the next release, and it’s got to be rushed. That’s why I’m putting it up to. you straight to work in with him now, and we’ll work in with you later, see?”

Reever Keene nodded curtly.

“I’ll try,” he said. “ But—I won’t promise.”

“The hell he won’t!” laughed the president later, when he was recounting the conversation to the director. “Like the rest of them—throwing a big bluff so he can strut around the Screen Club and tell how he handed it to me! Well, that’s one way of managing these here stars, believe me! This guy’s getting more money than the President of these here United States. Is he going to chuck his job?”

“Not him,” said the director confidently. “Besides, he’s under contract to us, and if he broke the contract—”

“He’d be finished, absolutely!” declared the president. “He’s no fool!”

The president was playing both ends against the middle, which is a wise game—sometimes.

IV

Reever Keene had been too long in the movie game, and was taking too much money out of it, to have any artistic temperament—that is, when he was on the lot. Movie folk have to keep their temperament out of business.

Still, when Keene saw what his director was doing to the abalone-pin story, and realized that he could not prevent its being done, he boiled with inward and suffocating rage. After three days he was so stifled with fury that he was ready for an outbreak.

He had put Jim Bleeker into that story, and when he saw how the director was handling Jim Bleeker, despite all protests, his fury became white-hot.

On the fourth morning he drove to the studio without opening his private mail. Once in his dressing-room, he glanced over the letters while he was making up; but, for him, that mail resolved itself into just one letter. He propped it in front of him and read it over again:

DEAR MR. LARRIGAN:

Within a few days I am leaving for Europe to take part in reconstruction work. I could not leave without writing you to express anew my very deep appreciation of all your thoughtful kindness to Jim. I know from his letters what your friendship meant to him, and I have learned from other comrades of your great devotion toward the end. Thanks seem but a little thing to offer; yet, believe me, my thanks and appreciation come from the soul.

I know nothing of your financial position or status in civil life, and I do not wish you to think that I am insulting so deep and pure a thing as your friendship with Jim. However, I am enclosing a card from my attorneys, who are fully instructed to honor it in any way. If you should ever be in need of advice or aid, it will give me great happiness to know that you will make use of this card as though it had been handed you by your friend,

JIM BLEEKER

“Bless her sweet heart,” muttered Reever Keene, tearing the card across and tossing it into his waste-basket. He smiled a little, as he thought of his twenty thousand dollars in cash, buried where no one would ever detect it; and of the Kansas oil stock, held by a friend, which brought in itself a comfortable income. Everybody in the business thought that Reever Keene blew all he had, like every one else; but Aloysius Larrigan knew better.

He read the letter again, fingering the blister pearl in his scarf, and forgetting his make-up completely. Once more he was standing in that house, half a block off Fifth Avenue; once more he was living through that moment when Mrs. Bleeker had handed him that scarf-pin, with her quiet, steady voice, and her brave, stricken eyes.

The thought of it made him sit very quiet, staring at the letter. In all his life he had never experienced a moment such as that; no not even when Jim had died, beside him! It had been a moment of the spirit; a moment of absolute integrity, of purity, of unsullied sweetness.

That moment had assoiled many long-soiled years. It had grown upon Larrigan ever since, had grown larger, had grown to mean much more than he had dared admit. Now this letter had come to bring it before him again in all its larger aspects.

He made up mechanically and went out on the lot; for an hour he acted mechanically, obeying the director without protest, without thought. Then, during a change in the set, he went to his dressing-room.

Lola was there, standing at his table, reading the letter. Something went cold inside Reever Keene, and he stepped forward as if to take it from her. But she turned upon him, a flood of passion in her face.

“Well,” she observed with a sneer, “I guess I got your number now, Mr. Larrigan! Lady signs herself Jim Bleeker, does she? Maybe we’re goin’ to hear a lot of things that happened—”

“You’re making a mistake, Lola,” said Reever Keene.

“Mistake, am I?” She shook the letter at him with sudden passion. “Maybe I don’t know a chicken’s writing when I see it, huh? Well, if you think I’m a fool, this ends it! You can go along with your Jim Bleeker all you damn please! When you get ready to talk turkey to me—”

Lola drew off the walnut diamond and laid it, very carefully, on the corner of the dressing-table under Reever Keene’s nose. The whole action was very statuesque and very dramatic; at least, was so intended.

An instant later Lola uttered a despairing shriek. Reever Keene had seized the walnut diamond and had hurled it through the open window—hurled it with a swing that sent it glittering through the air to Heaven only knew where!

“Ends it, eh?” snapped Keene. “Then I’m blamed glad of it! So-long!”

Lola fainted as he vanished, and immediately the dressing-corridor was filled with figures answering her final dramatic shriek. Reever Keene went outside and climbed into his plain green-black car and drove down the street to his lodgings.

Once there, he wiped the paint from his face, with a curse, and began to pack up his things. He paid his landlady. He burned Mrs. Bleeker’s letter over the oil- stove. Then he threw his stuff together in the rear of the car, and drove down to the bank, where he drew what money he kept deposited there.

This finished, he went to the central gasoline station and turned over his car to be filled with gas and oil, and to be loaded with sundry extra five-gallon cases of the same.

While he was watching these affairs being brought to conclusion he heard a wild hail and saw the president’s car stopping at the curb, and the president himself descending, red and perspiring of face.

“Hey, Keene!” demanded the magnate heatedly. “ What the devil’s struck you? They said you blew out o’ the studio like a wild man and quit work! Get on back there—”

“Go to hell!” snapped the star. “I’ve quit being Keene. I’m Aloysius Larrigan, see? And don’t get fresh, you!”

“What! Where you going?”

“I’m going to Kansas, where I got business,” retorted Larrigan. “Hurry up with them two cans of oil, over there! And blow up the extry tires while you’re about it, partner.”

The president seized him by the arm.

“Look here, you!” he exploded violently. “Are you quittin’ on the job—quittin’?”

“I am,” said Larrigan coldly.

“By Heaven, if you bust this contract I’ll see to it that you never get another job in front of any damned camera in the world!” raved the other. “I’ll—”

“You,” said Larrigan, “and your contract, and your seventeen companies, and your directors, and your money, and your whole damn camera battery, and your entire double-dashed motion-picture industry—go to hell! I’m done! Mustered out!”

He shoved a greenback at the gasoline, dealer, climbed into his car, and went. The president gazed after him with eyes of dulled, glazed despair.

“Bein’ in the army—that’s what done it for him—ruined the best star in the whole damned works!” he murmured dismally. “Damn the Kaiser!”