Читать книгу Inspector Ghote, His Life and Crimes - H. R. F Keating - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

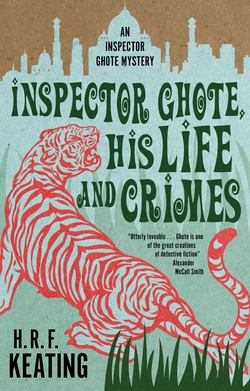

AUTHOR’S NOTE His Life and Crimes

ОглавлениеInspector Ghote came to life one day in 1963. I was sitting in my study, in the red armchair by the window – I have told this story so many times that some of it must be true – reading a geography book. I had decided that my next detective novel was to take place in India, a country I had never set foot in, and I was hard at work mugging up some facts.

Up until that moment I was convinced that my reason for taking this odd and even hazardous step was a strictly commercial one. American publishers had rejected my previous four titles as being ‘too British’. So how to avoid that stigma, and enter the lush transatlantic pastures? India seemed one answer, especially as I had had it in mind to write a crime story that would be somewhat of a commentary on the problem of perfectionism, and one of the few notions I had about India was that things there were apt to be rather imperfect. Good symbolic stuff.

Then, out of nowhere, into my head there came this man. Or some parts of him. A faintly worried face. Certainly, a pair of bony shoulders. A certain naïvety, which should enable him to ask the questions about the everyday life around him to which my potential readers might want answers. And he also brought with him a name: ‘Inspector Ghosh’. Oh, gosh, he would keep saying, wide-eyed.

It was only when I sent the outline of my Inspector’s adventure to a friend, an Englishman just back from Bombay, that I learnt that Ghosh is a Bengali name. It would be as unsuitable for a Bombay detective, at the other side of the Indian sub-continent, as Ivan Ivanovitch would be for a Parisian sleuth. He suggested the similar, but appropriate Maharashtrian name of Ghote. So, from birth we had advanced to christening or, more correctly, to the naam-karana, the name-giving ceremony.

At that point, however, I saw Ghote’s life as being a short one, a single book’s span. My speciality in 1963 was detective novels without a running hero, but with in each a different, more or less exotic background. There had been a coach-and-four trip, Zen (if in an English country house bleakly devoted to further education), the playing of croquet and a provincial opera venture. I saw India as just one more in that series. But the book, called of course from that running-thread of perfectionism The Perfect Murder, unexpectedly won the Gold Dagger award for 1964, and an Edgar Allan Poe award in America where, yes, it did get published. Ghote was granted an indefinite extension of life.

So in 1966 he underwent Inspector Ghote’s Good Crusade, in which he investigated the murder of an American philanthropist, was harassed by a fearful squad of Bombay street urchins, was grossly deceived when he gave all he had saved for a refrigerator to the apparently poverty-stricken ‘paramour’ of a fisherman and learnt (alongside, I hope, the reader) that giving is not always a straightforward business. He also solved the case. This was something he was contracted with his public to do, and because of that I was beginning to realise he would have to lose a little of his naïvety. Or, rather, he would have to develop an inner toughness and shrewdness not at first apparent.

I once heard the distinguished and delightfully reticent novelist, V. S. Naipaul, pronounce – in answer to a television interviewer who had asked what was the most important quality a novelist needed – the one word ‘Luck’. I think he was right. Certainly, it was my immense luck that the man who entered my head that day as I sat in my armchair proved to be a person with enough of myself in him to be able to turn this way and that, confronted by new aspects of life, and find new things in himself to match up to them.

So, in 1967 it was Inspector Ghote Caught in Meshes, when he looked at life as a tugging of different loyalties and became involved for the first and only time in something approaching the espionage novel. In 1968 it was Inspector Ghote Hunts the Peacock, where he came to London and discovered not only who had murdered a distant relation of his wife, a young woman known as ‘the Peacock’, but also the pluses and minuses that go with a sense of pride (Pride = peacock. Geddit?).

It was in the course of this book that I hit on a nasty little snag which I had in my innocence – or indeed sheer ignorance – created for myself. Needing a name for the wife I found that Ghote had, or had to have, while writing The Perfect Murder, I had chosen at random the pretty ‘Protima’. Only to be told later by one of the kindly readers who send me what I call ‘But’ letters – Dear Mr Keating, I much enjoyed … But I must point out an error … – that Protima is a Bengali name. So in Hunts the Peacock I boldly stated that Maharashtrian Ghote had, unusually, married a Bengali.

It was twenty years later, while I was writing the script for the film of The Perfect Murder with the director, Zafar Hai, that I learnt there is in fact a Maharashtrian version of the name, Pratima. So in the film Ghote’s wife is a Maharashtrian, as different from a Bengali as Spaniard from German, and is deliciously played as such by Ratna Pathak, the wife of Naseeruddin Shah, our star. So is the film-Ghote not the book-Ghote? Knotty philosophical point. Certainly, in Naseer Shah’s performance he is very much the Ghote I had in mind. Or perhaps the Ghote I had inside, because Naseer said once that he had been given the clue to the man by looking in the eyes of his creator.

But there is a complication, or even two: a radio-Ghote and a TV-Ghote. In 1972 I was asked (I think) to write a radio play about Ghote and produced Inspector Ghote and the All-Bad Man, followed by Inspector Ghote Makes A Journey and Inspector Ghote and the River Man. Feeling with the latter that I could not see the situation sufficiently without being able to describe its setting as well as entering into Ghote’s head, I began to write in narrative form before making it into radio dialogue. That torso tale, completed, is one of the stories here. In the second play I had Ghote coming to London a second time, as a planted stowaway among a party of illegal immigrants; and in a television play I wrote in 1983 (a semi-pilot for an abortive series), Ghote came to London yet again as a paying guest in the home of an ancient British Raj couple.

There was, too, an earlier television appearance in a version of Hunts the Peacock written by the Irish playwright, Hugh Leonard (who kept Ghote mercifully as he is in the book), with my hero acted by Zia Moyheddin. (Incidentally, he gave Ghote a moustache, which he just has in Inspector Ghote Goes By Train, but which he has never had at all by the time of the following books.) Now did he, my Ghote, book-Ghote, come to London more than once? His other visits certainly do not seem to be in my mind when I embark on the business – absurdly daring if you let yourself think about it – of holding in my head that whole different world in which there is a person called Ghote who has a wife called Protima, perhaps Pratima, and a son called Ved.

Here again we are back to complications. How old is Ved? Seen first in The Perfect Murder, he was big enough to sleep in a bed. When filming the scene in which Protima accuses Ghote of leaving her to cope on her own with a suddenly fever-ridden Ved – as an illustration to a BBC documentary about myself and the Bombay police – he appeared to be as old as ten or eleven (the only boy we could easily get hold of). But in the film of The Perfect Murder, because Naseer and Ratna Shah had a charming baby about a year old, Ved slid rapidly back to early infancy. Just one in 1988, but ten in 1974?

Whereas I can keep Ghote himself more or less stationary in age (though what exactly that age is depends, I suspect, as much on who is reading about him as on who writes about him) and I can keep his Protima ever elegant, ever her same self, a small boy must grow. So as the years pass my book-Ved gets bigger, though not by quite as much as the passing years dictate. If he did, his poor father would reach the early retirement age of the Indian Police Service much too soon for me, and the ore I mine so happily would abruptly prove exhausted.

It was shortly after Inspector Ghote Hunts the Peacock – to abandon the chronological complications – that I happened to write a short story called ‘The Justice Boy’ for a contest for British writers organised by that splendid American publication, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Set in an English prep school, it won the second prize, running-up to that Golden Age great Christianna Brand. As a consequence Fred Dannay, the other half of the pseudonymous Ellery Queen who then edited the magazine, wrote to me asking if I had any more stories.

So, in response, Ghote was set to begin a parallel life at shorter length and the story I eventually sent was the one that opens this volume, ‘The Test’. It illustrates the amount of Harry Keating that there is in Ganesh Ghote (although he had not in fact discovered his first name as early as this), because the incident in which the small Ved is overcome by horror when he thinks his father has vanished happened to me when I was much that age and my mother, not usually a practical joker, took it into her head to hide from me.

However, Ghote did not live any more of his life in short stories for a year or two after that first small, but quite characteristic, appearance. Instead there was Inspector Ghote Plays A Joker, in which he solved the murder of a rajah who, unlike my mother, was an inveterate practical joker. Hovering, as it were below the surface here, there were thoughts about games and games-playing in life.

Then there was Inspector Ghote Breaks An Egg, which took him out of Bombay to a small town in Maharashtra. This was one of the problems I faced: not to use and re-use the same setting, especially as my knowledge of never-visited Bombay was still confined to what I was able to discover about it from books, from the occasional Indian art-film featuring the city, from scraps of friends’ talk, from TV glimpses and from the pages of the Sunday edition of the Times of India, which I had begun to take. But in any case half my research went not outward, but inward. And there I discovered for my pages things about violence, the evil of violence and the good that sometimes cannot be brought about without it.

It was not until the end of 1971 – when I was asked by a friend, Desmond Albrow, then editing the Catholic Herald, to write a Christmas story for him – that short-story Ghote came to life again. The story, called variously ‘Inspector Ghote and the Miracle Baby’ or just ‘The Miracle’, is the second in the pages ahead. In it I incorporated – rather impudently, since I was writing for a religious paper – a quality I had had to give to Ghote which is not particularly characteristic of Indian police officers, or of most Indians. I made him an unbeliever. Since I had arrived at that state myself, I found I could not – seeing Ghote as I do from an angel-over-the-shoulder position – enter properly into his mind if it was to be filled with simple belief. Imagine, then, my dismay when at last I got to India three years later, met Bombay CID officers and saw almost invariably under the glass tops of their desks a picture of a god. Imagine, too, my slightly lesser dismay when I realised their desks had the glass tops necessary in a stickily humid climate, as Ghote’s had never had.

Short stories about Ghote were not exactly pouring from my pen, principally because there was hardly anywhere for them to be published. So he continued his life in books. In 1971 it had been Inspector Ghote Goes By Train, when I was able to make use of the mountain of Indian train lore I had accumulated – the extraordinary Indian railway system sets people a-writing and a-filming by the score – and send him (possibly moustached) all the way from Bombay to Calcutta and back, beset as ever with the difficulties that are a condition of his existence but triumphing finally, if not always to the complete satisfaction of his superiors.

Indeed in the next of his adventures, Inspector Ghote Trusts the Heart, in which he is put temporarily in charge of a child-kidnapping case – I had read a three-line story in The Times about the son of a rich man’s chauffeur in Japan snatched in mistake for his own boy – he ends in terrible hot water for having continued to hunt for the victim unofficially, and successfully: for, in fact, trusting his heart over his head.

One other short story then followed, written originally with an airline while-away in mind, though it eventually appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine: ‘The Hooked Fisherman’, as Fred Dannay (who never could resist altering a title) called it in place of my ‘The Not So Fly Fisherman’. I had hoped that with its gentle knocking of the bucket-shops which got round the law – as it then stood – about cheap seats, BOAC would lap it up. But airlines stick together and my ingenious use of the cover of the Bombay telephone directory, a volume I had discovered in my local library, never entertained any in-flight passengers.

One more book carried Ghote onwards before I too, became a passenger to Bombay. This was Bats Fly Up for Inspector Ghote, a consideration of suspicion, suspiciousness and its consequences – good and bad – occasioned by dinner-party talk with a senior Pakistani Customs official in London. It begins with a wild inaccuracy. As I had already hinted at in ‘The Miracle Baby’, I put poor Ghote on anti-pickpocketing duty. But this, I was soon to discover, was as unlikely as detaching a Scotland Yard Murder Squad man to move on the traffic.

Then one morning, some time in 1974, I got a letter from Air India saying they had heard of this author writing about Bombay without ever having seen the sub-continent, so would I like a flight there in exchange for whatever publicity there was to be made? Immediate reaction: marvellous, now at last I can overcome the financial difficulties of staying in India for adecent period. Subsequent reaction: Oh God, but what if those real smells, those real crippled beggars, those real lepers so appal me that I can no longer write about their city? A justifiable fear. Holding imaginary worlds in your head is achancy business at best.

But I thought eventually that it would be chicken indeed to turn down such an offer. So on 12 October 1974, with eight novels, three radio plays and four short stories about Inspector Ghote behind me, I set foot for the first time on Indian soil. On landing, I had intended to say, if possible not aloud, ‘One small step for Harry Keating, a giant stride for Inspector Ghote.’ But instead, struck as if by an immense hot, damp wash-cloth by Bombay’s post-monsoon humidity, all that emerged was amuttered ‘Cripes.’

However, I spent three splendid weeks thereafter learning alot, mopping up atmosphere, filling notebook after notebook and finding there was not so much to correct in my notion of the city – only, rather, things to enhance what I had managed to put into my subconscious and thence onto the pages. Everything was more than I had believed. The colours were brighter. The clamour was louder. The rich were richer. The poor were, yes, poorer and occasionally more outwardly wretched than I had been able to conceive of. Yet I was able to accept that. My fears had proved grou dless. I credit the power of the imagination. I had seen in my mind’s eye the worst, if not quite the whole, already. I suffered no crippling culture shock.

In fact, I followed up that first visit with another soon afterwards. I had had the temerity to put to BBC Television the idea of making adocumentary about this writer who had, for so long, chronicled the life of a Bombay detective without ever having seen his stamping ground, and who now at last was doing so. The BBC had taken up the idea, but tactfully left me to make my first visit unencumbered. Now, seven months later, we pretended to maks that visit again. In between and during filming, I filled yet more notebooks. And I had abonus. As a strand in the documentary, we filmed the work of the Bombay police as it really was. So I got to see, amid much else, the office, the ‘cabin’ of the head of Crime Branch CID, Ghote’s boss. I got to interview him, too, and Deputy Commissioner Kulkarni said, on air, ‘I would like to have Ghote on my team. He has the essential quality of being able to put himself into the mind of the criminal he is seeking.’ Delicious praise.

But some of Ghote’s everyday circumstances did have to change as a result of what I saw. His boss’s rank shot up from Deputy Superintendent to Deputy Commissioner. His desk had mysteriously become glass-topped, losing the whorled, scratched and ink-stained top it had had as at the opening of the story ‘The Not So Fly Fisherman’, relic of school desks where I had sat learning amongst other more forgettable things the elements of English composition.

Ghote’s home, too, had to undergo a sea-change. In my earliest days with him I had read of houses in Police Quarters somewhere. But what I had failed to realise was that in incredibly crowded, sea-surrounded Bombay, where property values now compare with Manhattan, police officers, however high their rank, live in flats. So the house Ghote once occupied became for a while simply a ‘home’ and eventually took on bit by bit the characteristics of a flat, such as the ones in which flattered – and flattering – Crime Branch inspectors had entertained me.

So, how would all I had learnt affect what I was to write about Ghote after India? I worried. So I decided to try my unprentice hand on a short story. ‘Inspector Ghote and the Noted British Author’ has in it a version of a case Crime Branch was handling at the time of my visit, with the addition of a visiting author (one of the Bombay papers had described me with the delightful expression of the title) who makes more of a nuisance of himself than I hoped I had done, and is rather fatter than I hope I was.

When I had written some dozen pages of the story and Ghote was still in that cabin I now knew so well, receiving orders, I began to realise that visiting the scene of the crime has its pitfalls as well as its perks. I had put into those pages every detail of that big room, the positioning of the chairs in front of the desk (significantly different in Indian offices, but …), the map on the wall and what it showed, even the names of the police dogs on the duties-board. And it was then that I understood that absence from the scene can be a help to the writer; automatically cutting down the dross that obscures the picture. I had to go back and be pretty severe with the blue pencil. But in the story I was now able to show a side to Ghote, until then not in evidence, that he shares with real-life Indian police officers, the ability to obtain answers at the end of a fist. Or of an open slapping hand. It is something he and I do not have in common.

I gave the first post-India novel a background I had scented long before but had hung back from using till I had had a chance to see the real thing – Bombay’s film world, the filmi duniya as, picking up a few words of Bombay Hindi (a fearful bastard language), I had learnt to say.

Luckily, I had had an introduction to a film distributor who in turn introduced me to one of the superstars of the Bombay studios. Thus when Inspector Ghote became infected with an echo version of the dizzying ambition that is apt to afflict quite ordinary men and women who get caught up in the swirling spiral of stardom, I had in Filmi, Filmi, Inspector Ghote plenty of circumstances to place him in. He goes, for instance, to a star’s party – ‘Come. Come, Mr Keating,’ my star had said to me. ‘A small party, sixty-eighty people’ – and that affair is truthful to reality in every particular. On the other hand, when the star in the book is late for the auspicious ceremony that starts a film, the mahurrat, which must be held to the minute, it was my idea to have the clock stopped in the studio. And afterwards I think – I think – I heard this was done in reality.

Bit by bit, then, Ghote was learning about himself and about life. Or I was learning about Ghote. Sometimes a lot, sometimes just an extra detail, such as the chewy paans that can (filled with aphrodisiac and thus called ‘bed-smashers’) cost as much as a hundred rupees. They are to be found in the story I wrote for broadcasting in 1976, ‘The Wicked Lady’. Originally this was to be a pilot for a series where the authors would interrupt just before the dénouement and invite listeners to guess who done it. Shamelessly, I had pinched a plot from Agatha Christie and Indianised it. The series was abandoned, so I turned the tale into a straight story. It proved to be the last about Ghote for some years, while instead I contributed tales about a charlady sleuth, Mrs Craggs, to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Back in his novel life, in Inspector Ghote Draws A Line, the poor fellow – in the unlikely disguise of Dr Ghote, research scholar – is sent to the home of an ancient and cantankerous judge deep in the Indian countryside when the aged relic is threatened with assassination. There my alter ego came to ponder (with the reader?) at what point and how firmly you should say, ‘Thus far and no further’.

Ghote also makes a fleeting appearance, the most fleeting appearance possible, in The Murder of the Maharajah, a book set in 1930. In its last lines the Maharajah’s umbrella-toting schoolmaster expresses a hope that if he is ever to have a son to add to the tally of his numerous daughters that boy will become a police officer. It is then revealed that his name is Ghote. Safe to write this much pre-history. But later, when I came to set down incidents from my hero’s childhood, I am not sure that I didn’t occasionally add confusion to what is called in India his ‘bio-datas’.

Two more book-length accounts add to the picture before Ghote appeared in a short story again. In Go West, Inspector Ghote he found himself ordered off to America, California even, and discovered that that extraordinary part of the world is a place steeped in a mysticism which strongly contrasts with materialist Bombay. He only solved the locked-room murder when he admitted to the existence of that mystical phenomenon translocation of the body (instantaneous travel, if you like, often over hundreds of miles). Atheist with all the ardour of the convert that I am, this was something that I had had to acknowledge as likely when during my first visit to India I met the representative of a pharmaceuticals firm. He had hailed me out of the darkness of the evening, recognising me from smudgy newspaper photos, and then recounted to me unabashed stories of a friend capable of summoning out of the very air money and sweets and more. Why should he have told me tarradiddles? He was a serious fellow, and not unscientific. (His job I borrowed for one of the suspects in ‘The Wicked Lady’.)

In The Sheriff of Bombay, which appeared in 1984, Ghote encountered his most harassing experience ‘till date’, as we say in India. He met sex. This was something I had not been able to bring myself to put into his world before, but during my second visit to Bombay I had been asked by one of the Crime Branch inspectors if I would like to see ‘the Cages’, the red-light area of Bombay regularly produced as one of the city’s sights, along with the Hanging Gardens (cover for a huge reservoir on top of Malabar Hill) and Elephanta Island. I had thought it my duty to succumb. The so-called cages – they are in fact no more than the barred windows behind which the girls display themselves – proved both sordid and lively, depending on the way I looked on them. So when ten years later I felt ready to use what I saw that night, The Sheriff of Bombay (that name I had seen on a plaque in the stern splendour of Bombay’s Gothic-style Old Secretariat) taught Ghote, myself – and, I trust, my readers – that much in life can appear either black or white according to the way it is seen.

Now, for some reason or another, I entered on a whole spate of short stories about the man who over the space of some ten years had come to occupy such a deep niche in my mind. Frequently now, seeing some sight or hearing a few words that particularly caught my attention, I would ask, ‘How does Ghote react to that?’ and know the answer. Some such questions have already resulted in books or stories. Others lie waiting, either like the pearls maharajahs were apt to hide away too long in the dark strongrooms of their palaces only to fade into colourlessness, or else perhaps to prove ever-shining diamonds.

In answer to a request from the editor of the magazine of the Townswomen’s Guilds, Ghote had an encounter with a party of ladies touring India and demonstrated that latent toughness that gives the tale its title, ‘The Cruel Inspector Ghote’. I think that quality came to Ghote’s surface when it lodged itself in my mind as I read a life of Rudyard Kipling, which pointed out that in The Jungle Book fatherly Baloo the Bear is wholesomely strict with young Mowgli. Then, in answer to a request for something filmable from a charming young woman rejoicing in the typically Indian nickname of Pooh, I wrote ‘Murder Must Not At All Advertise, Isn’t It?’. It was a passing tribute to my predecessor in detection, Dorothy L. Sayers, and set in the Bombay advertising world where Pooh Sayani made her living. In it, of course, was a charming creature called Tigga.

Although no film eventuated, the story, which shows a Ghote who has now just about got the balance between softness and shrewdness right, winged its way across the Atlantic to see the light of day there, complete with the third or fourth villain I had called Budhoo. So I crossed out that name in the long list I have in the front of my alphabetical notebook of things Indian. Ghote, lucky fellow, must have learnt the infinite complexities of Indian nomenclature as he grew up. But somehow he has been slow in passing on his knowledge to me, though nowadays, with care, I think I get most names right.

At much this time, too, I transcribed one of my old radio plays into short-story form, making The All-Bad Man into ‘The All-Bad Hat’. The story sums up, I think, where Ghote had got to by 1984. I also contrived, when the Police Review asked members of the Crime Writers Association for stories with a police setting, to get into words a small project I had long meditated – a story to be told purely in telephone conversations. ‘Hello, Hello, Inspector Ghote’ is my tribute to the magnificent imperfections of the Bombay telephone system, now considerably improved as Ghote notes in his 1988appearance, Dead on Time.

In 1986 Ghote experienced existence in what, I suppose, has been his most comprehensive coming-to-life yet. In Under A Monsoon Cloud, I set out to consider the theme of anger, a quality which, looking back, I see was something in others which Ghote had singularly failed to come to terms with. But anger had also given him on more than one occasion an impetus helping an essentially nice man to take the sharp action which often brings about success in an ugly world.

So I recalled an episode I had been told by a former Commissioner of the Bombay Police, for whom I had felt bound to write a disclaimer as a preface to Inspector Ghote Trusts the Heart, which featured in a rather poor light such a Commissioner. Mr S. G. Pradhan, with immense kindness, had contacted me in Bombay and given me several hours of his time, for much of it explaining complications of Indian police life which I found dauntingly difficult to get into the pages of an onward-pressing story. One particular illustration he used certainly lodged in my mind. It concerned an officer of great promise who in a moment of rage had killed a subordinate. Now was the time to regurgitate those facts-from-life as fiction-facts in the life of Inspector Ghote.

In the story that unwound itself in my head as a consequence of a similar rash act on the part of Ghote’s admired superior, ‘Tiger’ Kelkar, Ghote finds himself arraigned before a disciplinary tribunal. Conducting a defence of himself – as well as considering whether he ought to defend himself at all – I found he was bringing to the surface his whole attitude to life. ‘What good would I be as a security officer?’ he demands of his wife in the dark of the marital bedroom when the idea of resignation is in the air. ‘Oh, I could do that job all right, but what satisfaction would be there?’ (The phrasing comes from a notebook I have kept for twenty years, labelled and re-labelled ‘A Little Book of Indian English’.) Then he flares out: ‘It is not as if I have not been a good officer. Have I taken bribes? … Have I toadied and treated reverently superior officers? No, I have never so much as held open one car door to them. Have I had suspects beaten up even? … Did I buy my posting to the CID? And now am I to lose everything after I have sweated every ounce of my blood?’

It was while I was in hospital having a ruptured knee-tendon hooked back into place and dealing, a little bad-temperedly, with my editor’s queries about the next Ghote novel, The Body in the Billiard Room (in which in the appropriately lingering Britain-of-the-1930s atmosphere of Ooty hill station Ghote finds himself harassed, as it were, by the shade of Agatha Christie and solves a murder in more or less the manner of a Great Detective), that I conceived the notion of the short story I called ‘Nil By Mouth’. Those words, odd when you come to think about them, I saw day after day above the beds of patients about to go to the operating theatre, and from the fascination the phrase exercised over me grew that quite intricate little tale. It shows once more, at one and the same time, the just-tough Ghote – tough enough by now to defy at least hospital authorities – and the perhaps too-easily-moved Ghote.

Ghote’s major adventures appear at about yearly intervals, giving me time between books sometimes to embark u asksd on ashort story such as ‘APresent for Santa Sahib’, another Christmassy tale.

A gap between books was the origin, too, of ‘The Purloined Parvati and Other Artefacts’, though its deeper beginning-point lay in a visit I paid to an extraordinary private museum when I was attending, as chairman of the Society of Authors, the conference of our Indian sister organisation in Jaipur. I said to myself (as the enthusiastic owner took me round, together with a solemnly appreciative lady from UNESCO), that somehow I must give the place a parallel, scarcely exaggerated existence in fiction. Some eight years later Inspector Ghote, standing outside the little Press hut I had noticed during the filming of The Perfect Murder, was able to set out on that brief morning’s work. It enabled him to bring to the fore a capacity for critical judgement that had lain underneath the almost totally uncritical attitude he had possessed when authority figures had pronounced at the start of his career.

This capacity for objective judgement he retains, if sensibly inside his head, when in Dead on Time he dares to assess as mighty a figure as the Director General of Police for the State of Maharashtra. There he comes to terms, too, with his own attitude to the ever-pressing minute in time-ruled (though often time-flouting) Bombay, seeing that pressure in contrast to the almost timeless life of India’s villages. And it is in one of those, I discovered as I planned the book (or Ghote brought reminiscently to mind as he lived its events, as he does again in my final little tale ‘Light Coming’, where he is something of an authority figure himself), that Ghote had experienced various formative happenings. His life began there. Or did it begin one day as I was sitting in that red armchair in my study?

H.R.F Keating

1989