Читать книгу Paul Klee and His Illness - H. Suter - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

Оглавление‘This star teaches bending’ is the telling title of a work on paper which Paul Klee completed in the year of his death. This brilliant artist lived the last few years of his life in Bern, but they were years which were overshadowed by a dark star. In 1935 Klee suffered a variety of setbacks and became seriously ill. Although he never recovered from this illness, he always maintained his love of life, facing his suffering with a trenchant ‘so what?’ But by 1940 he had to accept that there was no hope of a cure or any improvement in his health. The star had taught him to bend to the blows of fate.

Paul Klee died in 1940 at the age of 60. He died of a mysterious disease which at the time remained undiagnosed: the symptoms included changes to the skin and problems with the internal organs. It was only 10 years after the artist’s death that the illness was actually given a name in writings about Klee. The art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler wrote in a publication: ‘His health was undermined for years by a terrible disease - a kind of skin sclerosis, which in the end was to carry him (Paul Klee) off’.1 Four years later, the Klee biographer Will Grohmann wrote in his 1954 monograph: ‘[…] it turned out to be a malignant disease (scleroderma), a drying-out of the mucous membranes which was little known in medical circles. After five years it spread to his heart and led to his death’2. We still have no idea where Kahnweiler and Grohmann got this information. It is strange that the diagnosis appears in neither the correspondence between the two married couples, Paul and Lily Klee and Will and Gertrud Grohmann,3 nor in Lily Klee’s memoirs4 which were written from 1942. The illness is also not identified in the notes published by Felix Klee, Paul and Lily’s only son, on his parents.5 Today it is no longer possible to ascertain where the diagnosis of ‘scleroderma’ for Paul Klee’s illness originated,6 and more recently the diagnosis has been called into question in medical circles.7

Fig. 5. Lily Klee-Stumpf, 1906

Fig. 6. Paul and Lily Klee with Bimbo the cat, Bern, 1935

In 1979, Professor Alfred Krebs, who at that time was Professor of Dermatology and Venereology at the University of Bern Skin Clinic, instigated research into Paul Klee’s illness. We talked to the artist’s son8 (see above) and the descendants of the now deceased doctors in Bern who treated Paul Klee or who were close to him: General Practitioner, Dr. Gerhard Schorer9 and his locum, Dr. Max Schatzmann,10 his boyhood friend, associate professor Dr. Fritz Lotmar,11 and his consultant, Professor Oscar Naegeli.12 We also spoke to Sister Virginia Bachmann, head of the Clinica Sant’ Agnese in Locarno-Muralto,13 where the artist died on June 29, 1940. As patients’ records are only kept for 10 years, there was little hope that, nearly 40 years on, any trace of his medical history would remain, and unfortunately this was the case. So I had further lengthy conversations with Felix Klee14, Max Huggler15 and other people who knew the artist personally16 or who could possibly contribute something with regard to his illness.17 Professor Krebs got in touch with the management of the Tarasp sanatorium in Unterengadin,18 where Klee went for treatment in 1936. He also checked the archives at the Bern Dermatology Clinic, where the painter consulted with Professor Oscar Naegeli in the same year.19 We made enquiries at the Institute for Diagnostic Radiology at Bern University to find out whether Paul Klee had undergone any tests or X-rays. However, as expected, there was no evidence of any medical records, X-ray pictures or analyses.20 I contacted both the administration and a former chief physician at the ‘Centre Valaisan de Pneumologie’ in Montana, as well as the local government of Montana and the canton administration in Sion to find out whether there was a patient file on Paul Klee for the year 1936 - he was recuperating at the ‘Pension Cécil’ in Montana at that time. I was informed that this pension was separate from the lung sanatorium, and it was not possible to track down any medical records for Paul Klee.21 Ms. Diana Bodmer, the daughter of Dr. Hermann Bodmer, who was the last doctor to treat the artist in Locarno, was also unable to bring us any further forward.22

The only piece of laboratory evidence that we have is the result of a urine test carried out at the Clinica Sant’ Agnese in Locarno-Muralto during Klee’s final days. This was sent to Professor Alfred Krebs by Sister Virginia Bachmann in 1979.23

I have been fascinated by Paul Klee and his art since my adolescence, and this spurred me on to continue my research. Would I ever get a clear picture of the artist’s illness? I was keen to find out whether there was any evidence to support or contradict the assumptions about his illness, so I studied notes and letters from the painter himself, from family members, friends and acquaintances, and also documents from the Paul Klee’s Estate. Felix Klee gave me copies of the extensive correspondence between his parents (particularly Lily Klee) and Will and Gertrud Grohmann, much of which was previously unpublished.24 These documents helped me to piece together an idea of the course of the illness and some of the symptoms, and Felix Klee filled me in on other important facts during our conversations.25 I was also helped in my research by the Bern-based Klee specialists and art historians Michael Baumgartner, Stefan Frey, Jürgen Glaesemer, Josef Helfenstein, Christine Hopfengart, Max Huggler, Osamu Okuda and Hans Christoph von Tavel, the nephew of Dr. Gerhard Schorer, who all provided me with invaluable information. The administrator of the Paul Klee’s Estate, Stefan Frey, was always ready to help with my research, and kindly put at my disposal an extensive, unpublished set of excerpts from letters.26 His exhaustive work on the documents gave me a solid foundation for my work.

I also studied the extensive literature on Paul Klee,27 particularly his diaries from 1898 to 1918 and other writings by the artist and his son Felix Klee. Other helpful literature included: Will Grohmann’s seminal monograph, along with that of Carola Giedion-Welcker, Max Huggler’s perceptive work, Jürgen Glaesemer’s excellent texts and the collection catalogues he put together for the Paul Klee Foundation in Bern, as well as this foundation’s catalogue of works, Stefan Frey’s detailed chronological biography of Paul Klee, 1933-1941 (Frey 1990), ‘Erinnerungen an Paul Klee’ (Memories of Paul Klee), by Ludwig Grote (Grote 1959), and a perusal of many exhibition catalogues and press reviews. Also invaluable was the groundbreaking book ‘Krankheit als Krise und Chance’ (Illness as Crisis and Opportunity) by Professor Edgar Heim (Heim/ML 1980). I am also grateful for the specialist advice given to me by Professor Peter M. Villiger in his fields of rheumatology, allergology and immunology.

Fig. 7. Dr. h.c. Felix Klee, 1940

Fig. 8. Dr. Will Grohmann, PhD, and Gertrud Grohmann, 1935

Fig. 9. Dr. Max Huggler, PhD, 1944

To date, Paul Klee’s illness has been largely ignored by the medical profession, hence my desire to fill the gap in our knowledge. In all the literature on Paul Klee, there is still no extant specialist assessment by a dermatologist.

In 1978, the President of the ‘Società Ticinese di Belle Arti’, Sergio Grandini, asked the then chief physician of the medical department of the Clinica Sant’ Agnese in Locarno-Muralto, Dr. Enrico Uehlinger, to investigate the illness and death of Paul Klee in this clinic. Unfortunately nothing came of this, as Dr. Uehlinger surmised that records were possibly handed over by the clinic to a Japanese researcher.28 However, Osamu Okuda, art historian at the Paul Klee Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts, Bern (now research associate at the Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern), told me that this was not the case, and that the Japanese in question was called Sadao Wada.29 He said Wada was at the Clinica Sant’ Agnese in 1974 and had in fact made his own investigations, but these also turned out to be fruitless. He published his findings in 1975 in a Japanese art journal under the title ‘The Last Moments of Paul Klee’.30 It mainly contained photographs of the house where the Klees lived in Bern, Klee’s tomb in the Schosshalden cemetery in Bern, the Viktoria Sanatorium in Locarno-Orselina and the Clinica Sant’ Agnese in Locarno-Muralto. Wada also photographed the room where the artist died and the view from this room.

In my work I have the following basic objectives:

- To collect as far as possible all the information which still exists on Paul Klee’s illness

- To reappraise the hypothetic diagnosis of ‘scleroderma’. Could it in fact have been another disease?

- To consider whether his illness had an influence on his psyche and his creative work

- To look at Paul Klee’s later works in the light of his personality, social environment, his illness and his imminent demise

In Chapter 2 I have tried to write about the medical facts in a way which is understandable to the layman, and I hope that when reading Chapters 3-6, my readers will be infected by some of the fascination that I feel for the great man and his work.

Fig. 10. Dr. Jürgen Glaesemer, PhD, 1987

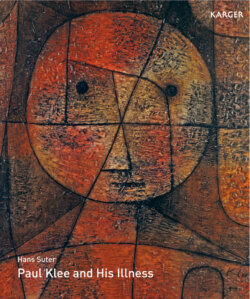

Fig. 11. Marked man, 1935, 146

Notes on Interpreting the Works of Art

Paul Klee had a very vivid imagination, and his art works and their titles in turn ignite the imagination of his viewers, adults and children alike. Upon finishing a piece of work, Klee would give it a pithy title. In the title he liked to give a pointer to help interpret his work, and at the same time he was very creative in his use of language. It is quite a feat of imagination that in around 9,800 works he very rarely repeated a title.

However, the titles still leave room for individual interpretation of the paintings and drawings. Klee was quite clear about this, saying to his viewers: ‘At the end of the day […], the signatures [by which he meant the picture titles] give a sense of my direction. But it’s up to you whether you decide to go my way, whether you take your own route - or whether you just stand still and decide not to come along at all. Don’t mistake the signature for an intention’31. In this respect, Will Grohmann was of the opinion that ‘He [Klee] tended to distance himself from his work, and talked about it as if it belonged to someone else. He was rarely satisfied; sometimes he would hint that there was a mistake and would challenge us to find it with an impish grin. But he would also tell us when he was feeling proud of certain works for one reason or another. When visitors came, he liked to take the opportunity to look at his latest output, which he otherwise didn’t take the time to do, and he inwardly expected his visitors to offer some objective criticism, or at least give a sign that they understood what he was trying to do. But he bemoaned the fact that most of them ‘didn’t add anything’, they just viewed his work with silent enjoyment. He was keen to find out the effect of his works-in-progress, the feelings and ideas they aroused; he needed this as a kind of checkup, but he was not at all unhappy if the viewer’s train of thought went in a totally different direction to his own. He knew this was a possibility and said ‘I’m surprised, but I find your interpretation just as good as and perhaps even better than mine’32.

Because of these comments quoted above, I have allowed myself to attempt some personal interpretation of his works. I do not in any way claim that my interpretations have any general validity, and must stress that I am not an art historian.

I wrote down my ideas spontaneously after in-depth viewing of his works. At times I may have projected too much into a picture, and I beg the reader for forgiveness if my imagination sometimes runs away with me.

Ultimately, the ‘soul’ of every work of art remains the artist’s own secret. Klee came up with an apt metaphor in this respect: ‘Art is a parable of Creation. The bond with optical reality is very elastic. The world of form is master of itself, but in itself is not art at the highest level. At the highest level there is a mystery which presides over ambiguity - and the light of intellect flickers and dies.’33

In this book, the illustrations showing Paul Klee’s works are mostly arranged in chronological order, so that we seem to be watching scenes from a film about the last seven years of the artist’s life.

Fig. 12. Ecce …., 1940, 138

Fig. 13. Bern with the Federal Parliament Building, Belpberg and the Bernese Alps