Читать книгу Goat Mountain - Habib Selmi - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

JAMES KIRKUP

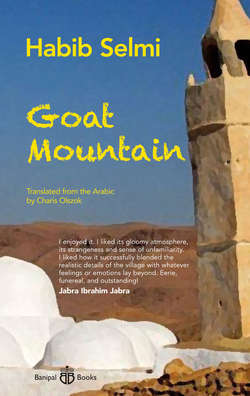

ОглавлениеThe intense, glacial fantasy that is Goat Mountain

This brief, stark and finally terrifying tale begins at home, on the eve of a son’s first departure for an obscure teaching post in a remote country school – a favourite theme in modern French literature also. It is a departure made with his father’s prayers and blessings and a mother’s joyful pride in her son’s first appointment, mingled with their sadness at the prospect of a long parting.

The journey begins, like so many African journeys, in a dilapidated old bus that takes four hours to reach Al-’Ala, from where the young man takes a long ride on mule back, accompanied by a mysterious older man who is to play an important part in the young man’s new life. As they proceed along desert tracks under a broiling sun, the youth begins to feel the first vague apprehensions about his silent companion. They make a brief halt at a solitary carob tree, where the man tells him seven men, including his own grandfather, had been murdered on the orders of the Pasha for taking part in an uprising against taxes. The young man begins to feel not just fear, but also an indefinable hatred for this “man about whom I knew nothing, except that he was the grandson of a rebel slaughtered in an obscure, mysterious land”. Thus the whole atmosphere of brooding horror and senseless violence is perfectly evoked in this first chapter, written like all the others in a spare, plain, factual yet strangely haunting style, with a secret poetic undercurrent that once or twice reminds us of Camus at his best. We remember the author’s epigraph from Pessóa’s Book of Disquiet: “We all live anonymously and apart from one another; in disguise, we suffer yet remain unknown . . .”

They finally arrive at Jabal al-’Anz – Goat Mountain – a forlorn, dusty desert village. The school is a single room. The youth passes the first night in the house of his uncommunicative guide, whose name is Ismail. The house is surprisingly well kept, with a large shelf of books: history, literature, Islamic law and Qur’anic exegesis. Next morning, they return to the school, where Ismail shows the young man his living quarters, a small room behind the class. Ismail tells him: “If you need anything, please inform me. I am the government’s representative in Goat Mountain.”

It is the beginning of a very strange sort of love-hate relationship between the two men – not exactly friends, but not yet enemies, either. Their association is composed of both elements, of which the sense of enmity begins to be the stronger. An increasingly unbearable tension develops between them, which is reflected in the life of the village. The young man grows more uneasy and depressed as Ismail becomes ever more powerful until, with a new truck and his own private army, he dominates village life and casts a menacing shadow over the young man until the latter reaches the verge of paranoia and madness.

This intense, glacial fantasy is the work of a literary master. At a subliminal level, it can be read as the intellectual’s despairing and suicidal attack on inhuman political power. It reminded me of the writings of two Africans I have translated: Camara Laye and Tierno Monénembo. From the latter’s brave novel Les Crapauds-brousse we learn the nickname taxis-brousse, given to all forms of primitive local long-distance transport, usually open trucks, or at best buses, like the one in Habib Selmi’s story.

Reproduced from

Banipal No 6, Autumn 1999