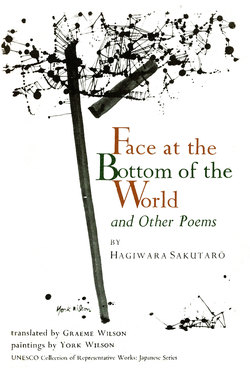

Читать книгу Face at the Bottom of the World and Other Poems - Hagiwara Sakutaro - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The poetry of Hagiwara Sakutarō is still little known in the English-speaking world, though this is not altogether surprising when the importance of his work remains inadequately recognized in Japan itself. Nearly all Japanese critiques of post-Meiji poetry acknowledge Hagiwara as one of the best (if not, indeed, the very best) of modern Japanese poets; but almost all critics, having briefly made some such admission, thereafter shy away from him, strangely to devote long paragraphs to other poets patently less talented, sadly more diffuse and far less influential. Why? Perhaps the reason is that Hagiwara, for all his brilliance, seems somehow to switch on darkness, to radiate black luminance. In the beaconry of modern Japanese literature he is an occulting, rather than a flashing, light: but he remains nevertheless a lighthouse of supreme importance.

* * *

Hagiwara was born on November 1st 1886 at Maebashi, a provincial town near Tokyo where his father was a successful doctor, initially in government service and later in private practice. The family was typical of the new Japanese middle class deliberately created by the policy-makers of the Meiji regime, and his home environment was characterized by its openness to then-modern influences: electric light, the magic lantern, ping-pong, western chairs and tables, summer holidays at the seaside, western playing-cards, the piano, the guitar, the mouth-organ. The eldest of six children, he was a sickly and hence a spoilt child, remaining his mother's lifelong darling. An unsatisfactory student, his failure to achieve the academic distinction of which he was obviously capable reflected as much a lazy man's unwillingness as a sick man's inability to concentrate. He neither went to a University nor ever seriously studied to develop his natural talent for music. Indeed, modern critics conscious of his proven genius show an understandable reluctance to say flatly whether some of the curious words in his poetry are deliberate new-coinings or merely results of his lack of formal education. On leaving school, he drifted into a vaguely Bohemian life and spent the years 1910-13 oscillating between Maebashi and Tokyo, reading, learning to play the mandolin, listening to opera, attending foreign plays, reviewing Kabuki performances, writing poetry. His father's disappointment was more than matched by the disapproval of his beatnik behavior evinced by the respectable bourgeoisie of Maebashi; and Hagiwara's poetry is full of acid and even vengeful references to his native place and its inhabitants.

His early poetry is all apprentice stuff in the traditional tanka form of five lines of 5:7:5:7:7 syllables. Nevertheless, by 1913 he had won a more than modest reputation as a new poet in that traditional mode, and had already decided to devote his life to literature. He formed useful friendships in the literary world; especially those with the then already well-established poets Yosano Akiko (1878-1942) and Kitahara Hakushū (1885-1943), and with two other excellent rising poets Murō Saisei (1889-1962) and Yamamura Bochō (1884-1924). Then, suddenly, in 1913, he began writing those astonishing and essentially modern poems on which his real and lasting reputation rests. His first book, Tsuki ni Hoeru (Barking at the Moon) appeared in 1917. It made an immediate impact, involved a brush with the Imperial Censor over the allegedly corrupting influence on the young of two of its poems (Person Who Loves Love and Ai Ren), and is still widely regarded as his most characteristic work. The rest of his life, in which, despite quick recognition as a leading contemporary writer, he largely depended for financial support upon his father, was devoted to producing a stream of books: six volumes of poetry, several of criticism, two major studies of poetic theory, a novel, an extremely influential study of Buson, and a flood of prose-poems, aphorisms, essays, articles, radio-scripts and miscellaneous writings.

In 1919 he married Ueda Ineko but, though two daughters were born (Yōko in 1920 and Akiko in 1922), the marriage was a failure and ended in 1929. A second marriage in 1938 to Ōya Mitsuko proved equally luckless, and she left him in eighteen months. The loneliness, nihilism and desperation of his later life are painfully reflected in his poems, and the posthumous account of him written by his daughter Yōko paints a poignant picture of the aging poet, fascinated by stage-magic and simple conjuring tricks, drifting into alienation and a persistent drunkenness. Kitahara Hakushū, in his introduction to Barking at the Moon, had likened the quality in Hagiwara's early poetry to that of a "razor soaked in gloomy scent", to the "flash of a razor in a bowl of cool mercury". The razor-edge was never seriously blunted, but its scent soured into the smell of stale beer; and Murō, in his poem on Hagiwara's death, significantly referred to the phenomena of continuing life as "for you mere saké spilt along the bar". Hagiwara himself explained his especial liking for beer as permitting long arguments about poetry as one proceeded slowly toward incoherence. Miyoshi Tatsuji, Japan's best poet between Hagiwara's death in 1942 and his own in 1964, has described long fascinating discussions with Hagiwara as he sat drinking steadily in his favorite corner of his favorite beer-hall in Shinjuku; but it is Hagiwara, and Hagiwara only, whom Miyoshi recognizes as his master. The poet's lonely life was lightened by a variety of new literary friendships; and the deepest (that with Miyoshi) lasted happily, save for some acrimony over the latter's frank confession or his dislike of Hagiwara's last book of poems (The Ice Land of 1934), until the poet's death of pneumonia on May 11th 1942.

* * *

Hagiwara began writing during that critical period in the history of Japanese literature when western influences, almost overwhelming in the Meiji Era (1868-1912), were at last being so successfully assimilated as to permit the re-growth of that essentially Japanese spirit which characterized the succeeding Taisho Era (1912-26). By 1910 the seeds dropped from foreign flowers, not all of them Fleurs du Mal, into the loam of Japanese consciousness were coming up like cryptomeria. Wakon yōsai, that Meiji slogan stressing the need to meld western learning and the Japanese spirit", was still a living inspiration; and Hagiwara, working in full awareness thereof, achieved universality.

It is still sometimes said that the artist's function is to hold a mirror up to nature. The time when that remark was true, if ever such a time there was, is now long past. The photographers have taken over; the photographers who implement the lawyers' pettifogging mania for reasonable facsimiles. The artist's function is (and has, I fancy, always been) to hold up mirrors that transmit not the photographers' literal reality but the artist's individual, even his cracked, perception of the universe. His function in the world is, I believe, to create unreasonable facsimiles thereof. For artists, especially lyric poets such as Hagiwara, are not concerned with truths verifiable by photographs, by the due processes of the law, or by the disciplines of formal logic. They have those reasons reason does not know. Hagiwara was once asked to explain the meaning of an early poem. He replied by asking if his questioner considered beautiful the nightingale's song. On receiving the inevitable affirmative, he then asked what that bird-song meant.... For Hagiwara holds no mirror, cracked or common-place, up to nature: mirrors need light. Instead, he turns a radar onto nature's hitherto unpenetrated darknesses, feeling out shapes invisible. The resultant images, shining, golden or greeny-silver, often indeed distorted, may, to a photographer's eye, seem odd; but they are authentic versions, visions even, of the truth. For Hagiwara was a native of that strange world where Dylan Thomas' question ("Isn't life a terrible thing, thank God") really needs no answer. And. of that world his poems are a terrible, but a beautiful, reporting.

Hagiwara's earliest truly modern poems, of which the first examples appeared in magazines during 1913, show traces of the influence of Baudelaire and the French Symbolists. He has, in fact, been called "the Japanese Baudelaire" but, though there are obvious resemblances in their attitudes, Hagiwara's poetry (as distinct, from his prose) contains none of the intellectualism of his predecessor. Similarly, those poems in which he shows most resemblance to Rimbaud are in the lighter lyrical field; and it is interesting to compare Hagiwara's Elegant Appetite with Rimbaud's Au Cabaret Vert) the latter the poem in which Ezra Pound considers Rimbaud's real originality to be found. Though Hagiwara's work rings with a certain natural pessimism and despair (themselves reflections of ill health, ill nerves and plain ill-luck), its tone was deepened by study of Nietzsche, Bergson and Schopenhauer. Not only his first book but also his middle-period poetry (notably the poems in To Dream of a Butterfly of 1923 and Blue Cat of the same year) exhibit that pure but desperate lyricism which German critics have called "the Keats sickness". These poems do not argue: they sing. They are, in Japanese, songs of those very nightingales which, in T. S. Eliot's poem,

"Sang within the bloody wood

When Agamemnon cried aloud

And let their liquid siftings fall

To stain the stiff dishonoured shroud."