Читать книгу Modern Hand to Hand Combat - Hakim Isler - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеchapter 1

JOURNEY TO CREATION

It was 6 a.m. as we formed up for physical fitness training (PT) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Orders for our PT uniform that day was that we were to wear battle dress uniforms (BDUs) and boots. The mood that day was a somber one, because we figured that there would be a long log run or some other difficult team building event, undoubtedly raising the “suck factor” of our lives. When cadre appeared, I remember getting that all too familiar feeling of anxiety that comes from finding out what was to come. We were given the eight commands necessary to get us ready to perform PT, and then we were informed that we would be conducting combative training.

I was 25 at the time and a newbie to the Army. However, since I was 8 years old, I had been studying the martial arts, so I had 17 years of experience by that point. You can imagine the my enthusiasm that morning after finding out that we would be studying combatives. Previously, I had only received a small block of instruction in basic training at Fort Benning. The training was not very impressive, but it wasn’t supposed to be. It seemed that the primary focus was to instill a fighting spirit in myself and the other soldiers. Now that I stood on the grass of “The Home of Special Operations,” I knew I would be learning things that would impress me.

As we began, I immediately felt like I had been thrust into a selection phase of a special school rather than a combatives class. For the next 40 minutes, we were ordered to perform a series of physical exercises designed to completely diminish our strength and energy. Although the others did not understand how this was related to combatives, I knew what was happening. I knew the cadre wanted us to be at a point of muscle failure so that when we were taught the techniques we couldn’t rely solely on our physical strength. With fatigue gripping our bodies, we’d really have to mentally focus to accomplish the techniques and achieve the desired results. I had seen this tactic used in several schools before, but never at such an early stage. I certainly thought that the techniques I was going to learn would blow my mind.

After the “smoke session” (an extremely high-paced and demanding work-out) was over, we formed a circle around the cadre. Finally, the cadre members started to demonstrate the techniques that we would be working on for the remainder of our PT time. As they started the demonstration, my mouth almost dropped to the floor. I wasn’t amazed at all. On the contrary, I was shocked. What I saw was very rigid, unrealistic, and unstable. The rigidity wasn’t much of a problem in my mind; I expected some of this, because it is sometimes easier to convey combatives this way when teaching to a crowd of people. The main problems were the unrealistic and hypocritical aspects of the techniques.

What I mean by unrealistic is that we spent our first 40 minutes of training being worn down so that we could not use strength, only to then learn techniques that only worked by using a great deal of strength. The cadre members were constantly yelling at the trainees to “pull harder, hit harder, or kick harder” when a technique wasn’t working. In my mind, I searched for a way to defend their methods. I told myself that they were just trying to instill a fighting spirit in us. But the fact is that they were yelling at people who couldn’t perform due to their fatigue. It made me wonder. In truth, it wasn’t spirit that was the problem; the techniques required too much energy and strength to be correctly performed.

So why did we start to succeed when we were yelled at? Well, no one wanted to hyperextend his or her arm because they were trying to be a successful attacker. So, what we started doing was taking it easy for the next attack or loosening our grip so that the defense could succeed.

Here’s another point: Let’s assume that both Soldier A and Soldier B are exhausted during a combative drill. Now, let’s have Soldier A attack Soldier B. If Soldier B can’t defend against Soldier A’s attack when exhausted, how is Soldier B going to successfully defend against a fresh and ready opponent? How can Soldier B hope to succeed, regardless of whatever sound combative technique he or she may be employing, if Soldier B simply cannot operate at full potential?

Another aspect I found unrealistic was that we were doing things like simulating arm breaks, rib breaks, and kicks to the face with combat boots, sometimes all in the same technique. What was our opponent doing as we performed our techniques? Unfortunately, more often than not, they were staring off into space. There was no reality-based consideration for the reaction of an attacker getting his or her arm or ribs broken, or being kicked in the face. Initially, I thought this was because we were in the beginning phase of our combative training. I had taught static training to beginners before, where there’s less of a consideration for “real” reactions during combat. However, as the classes continued, the consideration for reactions was never covered.

Along with this lack of consideration for realistic reaction was what I call the “Action Movie Syndrome.” This happens when people put too many movements into a technique set. Thus, you break an arm, then a rib, then strike the face, then the neck, and then have a cup of coffee before the guy hits the ground. Wow! It all looks very cool, but it is not efficient or effective—except maybe in a movie-generated situation. I don’t like to say that certain things or techniques will “never” work; you can, after all, cut a steak with a fork, but it’s going to be difficult. In a real fight, if you break an opponent’s arm, he or she now has a big problem. Even if he or she can continue to fight with one arm down, he or she would almost have to be a superhero. Or, this person would have to be extremely high on some substance to ignore the painful reality of a broken arm!

Furthermore, when you break someone’s arm, that person isn’t just going to stand there. You can bank on the fact that the attacker’s body dynamic is going to change. But what does that mean? Well, it might mean that the “Five-Combo Hurricane Kick” you were planning next won’t work that well.

Another major flaw I noticed as our combatives training continued was that everything was done with our legs nearly straight. The result was poor balance, with soldiers falling all over the place. There was no mention of bending one’s knees and getting low to the ground as a way to gain stability and maintain a better center of gravity. There was no mention that tall, straight legs meant lack of balance and weak technique. Maybe it was because we were just supposed to learn the basics; this was just an introductory course in combative training.

Well, guess what? The things I am talking about are the basics, and to neglect them at the beginning means bigger problems down the line.

Even though I felt so many things were a little off about what was being taught, I still had no real desire to work to ward making it better. Although I’d already written a book and created a curriculum for a self-protection art, I felt I didn’t have enough knowledge on the needs of the military to create my own comprehensive combatives system. Besides, my focus was on completing my military training. It really wasn’t until I made it to my unit, linked up with my team, and began training to deploy to Iraq that I started learning what service members would really need on the battlefield.

My first revelation came when I had to put my armor on and go out on a mock patrol. I remember feeling how awkward and heavy my armor was, and I wasn’t even carrying ammo yet. Because I had gone to bodyguard school before the Army, I was well versed in role-playing situations. I immediately started thinking about how would I fight with all this equipment on my person. Needless to say, the answers didn’t come from anything I was taught by that cadre on that early morning or the days that followed. The moves were too quick, unstable, required too much energy for what I was wearing.

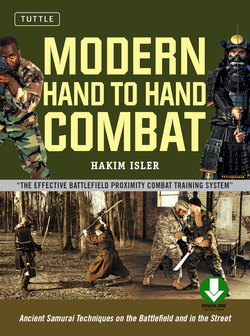

I started thinking about the last martial arts system I learned, which I studied for five years before joining the Army. Its principles and philosophies came from an ancient Japanese lineage where people often fought wearing heavy armor. I began to think more about the relationship between what I was wear ing and what the samurai wore on the battlefields of Japan. During training, I was told that I would spend at least fifty percent of my time in this uniform while I was in Iraq. So why, then, didn’t my training cover close-quarters hand-to-hand combat with this uniform? I thought more about those ancient principles and wondered if I could create a system based on them. After all, in both concept and reality, protective armor has transcended the span of time. Could those ancient combat principles transcend as well? The samurai were masters at warfare, could their teachings still be useful on today’s battlefield?

I started to tinker with this concept and began developing several techniques. Then one day, I found myself talking with a staff sergeant from my unit who had spent most of his Army career on the judo team—until he came to our unit. I told him what I was doing and he thought it was a great idea. He said he had talked to the First Sergeant and was going to be giving a ground fighting class for PT on Thursdays. He asked if I would be willing to demonstrate some of my newly developed techniques, because he felt it was geared more towards what we would really face on the battlefield.

I was elated, as you can imagine, but I had no official curriculum, so I told him I wasn’t sure if I was ready. He talked me into giving it a try, and I spent the next few days organizing my notes and techniques. When Thursday rolled around, we had, according to the participants, “a good class that made a lot of sense.” To some, my theories were revolutionary, further encouraging me to believe that maybe I really was onto something. I taught a few more classes before my unit scrapped the Thursday combative class to make room for other necessary training for deployment. However, I received enough positive feedback that I kept working on the curriculum.

Battlefield Proximity Combat (B.P.C.) seemed to grow from infancy to adulthood during my time in Iraq. It was on the ground there that I gained personal experience and had conversations with others about the battlefield and what was needed. In addition, I was able to conduct B.P.C. classes during my downtime at the gym. Class availability was mission dependent, but even when I couldn’t make it, the other practitioners would run their own classes, working on the material I taught in prior classes. The fact that they were capable of doing this in such a short time, again, proved to me that I was on the right track. During my 15-month tour, I trained a number of classes filled with men and women of the Army, Marines, and the Navy, as well as military contractors. It was fun and inspiring work.

This book is also a result of the time that I spent fighting and training in the desert. Mind you, I don’t believe that B.P.C. is the “ultimate authority” of all combative systems. But, it can be a great introduction to combatives, or a great addition to current or future training. I believe that everything—even the system I began learning on that early morning—has some value. Knowledge is the first step towards strength; the second step is its application.