Читать книгу An Island Odyssey - Hamish Haswell-Smith - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

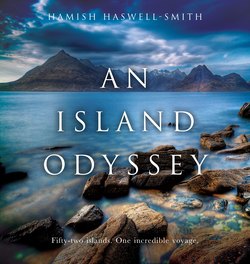

ОглавлениеSCARBA

. . . the famous and dangerous gulf, called Cory Vrekan. . . yields an impetuous current, not to be matched anywhere about the isle of Britain. The sea begins to boil and ferment with the tide of flood, and resembles the boiling of a pot; and then increases gradually, until it appears in many whirlpools, which form themselves in sort of pyramids, and immediately after spout up as high as the mast of a little vessel, and at the same time make a loud report. These white waves run two leagues with the wind before they break. . . This boiling of the sea is not above a pistol-shot distant from the coast of Scarba Isle, where the white waves meet and spout up: they call it the Kaillach, i.e., an old hag; and they say that when she puts on her kerchief i.e., the whitest waves, it is then reckoned fatal to approach her. . .

Once upon a time a handsome young prince sailed over from Scandinavia and fell in love with the beautiful daughter of a Jura chieftain. He asked for her hand in marriage, but her father had other plans. ‘No problem.’ he said. ‘Take your boat and anchor it for three consecutive days in the middle of the Gulf between Jura and Scarba and then you can marry my daughter.’

Prince Breacan agreed but he smelt a rat and asked the local sailors for their advice. The waters are dangerous and there is only one way to survive, they told him. You must use three ropes for your anchor, one made of wool, one of hemp, and one of virgins’ hair. So the prince travelled round Jura and Scarba collecting the materials and at last the ropes were made to his satisfaction. He then sailed his boat out to the middle of the Gulf and dropped anchor.

At the end of the first day the wool rope parted, and by the end of the second day the hemp rope had broken. Then on the third day it became clear that the island girls had not been entirely honest because the hair rope also broke and the prince was drowned. And the chieftain’s daughter lived unhappily ever after and the Gulf became known as the Corryvreckan (Breacan’s cauldron).

This sad little story is, of course, entirely untrue.

The flood tides from the Irish Sea run up the Sound of Jura building up a huge head of water which forces itself westwards out through the Gulf of Coire Bhreacain (‘the speckled cauldron’) and runs headlong into the incoming Atlantic tide. Down below this thundering collision, the bottom of the gulf has been shaped by a primeval cataclysm. A ridge runs out from Scarba with a high rock pinnacle on the end of it and in the centre of the gulf a narrow pit, like a gateway to hell, descends 100 metres below the surrounding seabed to an overall depth of 219 metres. The turbulent waters spin round the pinnacle creating a maelstrom. In westerly gales there are also enormous breakers, violent eddies and water spouts and the noise of these overfalls can be heard many miles away. It is one of Europe’s most dramatic seascapes and even at slack water, when it is possible to sail through the Gulf, the turgid eddies and whorls sucking at the surface create a palpable sense of menace.

Scarba itself is a rugged island, a single peak rising to a height of 449 metres above sea-level with many coastal cliffs and caves and set between two notorious tidal races – the Corryvreckan to the south and the Pass of the Grey Dogs to the north. The west flank is the most precipitous but the east side is gentler, with a small patch of land fit for cultivation, and some scattered woodland. This 3600-acre island once supported fourteen families but nowadays it has no permanent residents and belongs to the family of the late Lord Duncan Sandys.

Gleann a’ Mhaoil Bay – just round the corner from the Corryvreckan – has a beach of large, multi-coloured pebbles and a small cottage which is occupied in summer by the wardens of an adventure school. They train school children in survival techniques – how to live entirely off the land and use the caves for shelter. There is an interesting trudge up the ridge beside this bothy which Peter and I tried out a couple of years ago. . . up and over the ridge. . . and the next ridge. . . and the next again. The going was rough: tufts of ankle-twisting grass, heather, and bracken with boggy patches amid great swathes of ragged-robin and cotton grass. Behind the ridges a vestigial path ran alongside a small loch. Only a narrow earth barrier seemed to stop this lochan from emptying itself nearly 300 metres down the mountain-side. Following the ‘path’ round the contours until it disappeared brought us to the head of a steep gully which falls dramatically down to Camas nam Bàirneach (‘limpet creek’). Deer spied on us from every rocky outcrop and far below the largest of the Corryvreckan whirlpools was taking shape in a white froth. A thrilling viewpoint!