Читать книгу Erdogan Rising - Hannah Smith Lucinda - Страница 24

The ad man

ОглавлениеErdoğan was not the only Islamist mayor to have been imprisoned in Turkey at that time. In 1996 şükrü Karatepe, the mayor of Kayseri in central Anatolia and also from the Refah Party, had told a rally that his ‘heart was bleeding’ because he had been obliged to attend a ceremony honouring Atatürk. Convicted of insulting the eternal leader in April 1998, a week after Erdoğan’s conviction for inciting religious hatred, he had a one-year sentence slapped on him and was sent straight to prison with no time for appeal. But Karatepe did not have a marketing genius behind him – and he was forgotten as soon as his cell door slammed shut.

Erdoğan, meanwhile, was working with the best in the business.

‘Even when Erdoğan was forbidden from engaging in politics we were engaged in communication campaigns. There was a political ban on him but we were trying to do as much as the law allowed,’ says Cevat Olçok, the bearded and sharp-suited director of Arter, Turkey’s first political marketing agency. I am sitting across from him at a huge desk in the agency’s minimalist-industrial-style Istanbul offices in April 2018. The clean lines of the shelves behind him are ruined by Ottoman-style knick-knacks, books and framed pictures of Erdoğan. Pride of place, though, goes to the photos of his brother, Erol, and nephew, Abdullah, both killed on the Bosphorus bridge by coup soldiers on 15 July.

Erol Olçok, who founded Arter with Cevat, first worked with Erdoğan as a spin doctor in the Istanbul mayoral election campaign of 1994. He was raised in a poor and religious family in the Anatolian town of Çorum and, like Erdoğan, had graduated from religious high school. But instead of entering the clergy like most of his peers he went to art college – the first from his village to take advantage of higher education.

‘I will never forget the day I first passed the Bosphorus,’ Erol later said of his first day in the city in 1982.

In 1986 he graduated with a degree in art history and started working in advertising. It was a relatively new and rapidly expanding sector; prime minister Turgut Özal, the first elected leader after the 1980 military coup, was opening up Turkey’s economy and Turks were becoming consumers in the Western style. After working with a number of commercial agencies Erol started Arter in 1993, and a year later was contracted by Erdoğan. Such was the bond that developed between them that, having won the Istanbul mayoral elections, Erdoğan appointed Erol Olçok his press adviser.

‘Erdoğan never stopped marketing himself,’ says Cevat Olçok. ‘We were making greetings cards from him for religious holidays and important dates for the country. When he had the political ban, his motto was “this song does not finish here”. We designed the poster for everybody in Turkey. There was a huge demand for it. It was in every city in Turkey.’

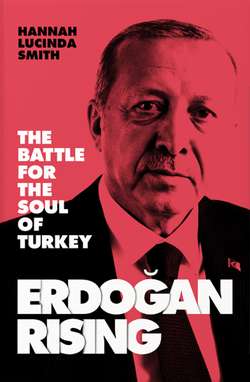

Arter’s iconic poster was the namesake of the later album of poetry: a picture of Erdoğan in profile, speaking from behind a podium with a Turkish flag in the background. At the top, his name. At the bottom, that slogan – a statement. And other than that, nothing else: no party logo, no symbol and no explanation. None was needed. Erdoğan had become a brand.