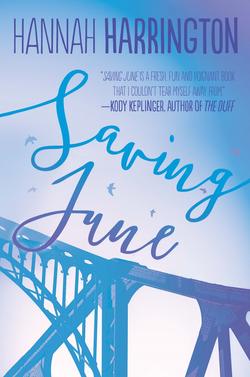

Читать книгу Saving June - Hannah Harrington - Страница 6

chapter one

ОглавлениеAccording to the puppy-of-the-month calendar hanging next to the phone in the kitchen, my sister June died on a Thursday, exactly nine days before her high school graduation. May’s breed is the golden retriever—pictured is a whole litter of them, nestled side by side in a red wagon amid a blooming spring garden. The word Graduation!! is written in red inside the white square, complete with an extra exclamation point. If she’d waited less than two weeks, she would be June who died in June, but I guess she never took that into account.

The only reason I’m in the kitchen in the first place is because somehow, somewhere, someone got the idea in their head that the best way to comfort a mourning family is to present them with plated foods. Everyone has been dropping off stupid casseroles, which is totally useless, because nobody’s eating anything anyway. We already have a refrigerator stocked with not only casseroles, but lasa gnas, jams, homemade breads, cakes and more. Add to that the lemon meringue pie I’m holding and the Scott family could open up a restaurant out of our own kitchen. Or at the very least a well-stocked deli.

I slide the pie on top of a dish of apricot tart, then shut the refrigerator door and lean against it. One moment. All I want is one moment to myself.

“Harper?”

Not that that will be happening anytime soon.

It’s weird to see Tyler in a suit. It’s black, the lines of it clean and sharp, the knot of the silk tie pressed tight to his throat, uncomfortably formal.

“You look … nice,” he says, finally, after what has to be the most awkward silence in all of documented history.

Part of me wants to strangle him with his dumb tie, and at the same time, I feel a little sorry for him. Which is ridiculous, considering the circumstances, but even with a year in age and nearly a foot in height on me, he looks impossibly young. A little boy playing dress-up in Daddy’s clothes.

“Can I help you with something?” I say shortly. After a day of constant platitudes, a steady stream of thank-you-for-your-concern and we’re-doing-our-best and it-was-a-shock-to-us-too, my patience is shot. It definitely isn’t going to be extended to the guy who broke my sister’s heart a few months ago.

Tyler fidgets with his tie with both hands. I always did make him nervous. I guess it’s because when your girlfriend’s the homecoming queen, and your girlfriend’s sister is—well, me, it’s hard to find common ground.

“I wanted to give you this,” he says. He steps forward and presses something small and hard into my hand. “Do you know what it is?”

I glance down into my open palm. Of course I know: June’s promise ring. The familiar sapphire stone embedded in white gold gleams under the kitchen light.

The first time June showed it to me, around six months ago, she was at the stove, cooking something spicy smelling in a pan while I grabbed orange juice from the fridge. She was always doing that, cooking elaborate meals, even though I almost never saw her eat any of them.

She extended her hand in a showy gesture as she said, “It belonged to his grandmother. Isn’t it beautiful?” And when she just about swooned, it was all I could do not to roll my eyes so hard they fell out of my head.

“I think it’s stupid,” I told her. “You really want to spend the rest of your life with that jerk-off?”

“Tyler is not a jerk-off. He’s sweet. He wants us to move to California together after we graduate. Maybe rent an apartment by the beach.”

California. June was always talking about California and having a house by the ocean. I didn’t know why she was so obsessed with someplace she’d never even been.

“Seriously, you’re barely eighteen,” I reminded her. “Why would you even think about marriage?”

June gave me a look that made it clear the age difference between us might as well be ten years instead of less than two. “You’ll understand when you’re older,” she said. “When you fall in love.”

I rolled my eyes as I drank straight from the jug, then wiped my mouth off with my sleeve. “Yeah, I’m so sure.”

“What, you don’t believe in true love?”

“You’ve met our parents, haven’t you?”

Two months later, June caught her precious Tyler macking on some skanky freshman cheerleader at a car wash fundraiser meant to raise money for the band geeks. The only thing really raised was the bar for most indiscreet and stupidest way to get caught cheating on your girlfriend. Tyler was quite the class act.

A month after that disaster, our parents’ divorce was finalized.

June and I never really talked about either of those things. It wasn’t like when we were kids; we weren’t best friends anymore. Hadn’t been in years.

Now, even looking at the ring makes me want to throw up. I all but fling it at Tyler in my haste to not have it in my possession. “No. I don’t want it. It’s yours.”

“It should’ve been hers,” he insists, snatching my hand to try and force it back. “We would’ve gotten back together. I know we would have. It should’ve been hers. Keep it.”

What is he doing? I want to scream, or kick him in the stomach, or something. Anything to get him away from me.

“I don’t want it.” My voice arches into near hysteria. What makes him think this is appropriate? It is not appropriate. It is so far from appropriate. “Okay? I don’t want it. I don’t.”

Our reverse tug-of-war is interrupted by the approach of a stout, so-gray-it’s-blue-haired woman, who pushes in front of Tyler and tugs me to her chest in a smothering embrace. She has that weird smell all old ladies seem to possess, must and cat litter and pungent perfume, and when she releases me from her death grip, holding me at arm’s length, my eyes focus enough for a better look. Her clown-red lipstick and pink blush contrast sharply with her papery white skin. It’s like a department store makeup counter threw up on her face.

I have no idea who she is, but I’m not surprised. An event like this in a town as small as ours has all kinds of people coming out of the woodwork. This isn’t the first time today I’ve been cornered and accosted by someone I’ve never met acting like we’re old friends.

“It’s such a tragedy,” the woman is saying now. “She was so young.”

“Yes,” I agree. I feel suddenly dizzy, the blood between my temples pounding at a dull roar.

“So gifted!”

“Yes,” I say again.

“She was a lovely girl. You would never think …” As she trails off, the wrinkles around her mouth deepen. “The Lord does work in mysterious ways. My deepest sympathies, sweetheart.”

The edges of my vision go white. “Thank you.”

I can’t do this. I can’t do this. It feels like there’s an elephant sitting on my chest.

“There you are.”

I expect to see another stranger making a beeline for me, but instead it’s my best friend, Laney. She has on a dress I’ve never seen before, black with a severe pencil skirt, paired with skinny heels and a silver necklace that dips low into her cleavage. Her thick blond hair, which usually hangs to the middle of her back, is twisted and pinned to the back of her head. I wonder how she managed to take so much hair and cram it into such a neat bun.

She strides forward, her heels clicking on the linoleum, and only meets my eyes briefly before turning her attention to Tyler.

“Your mom’s looking for you,” she says, her hand on his arm. From the outside it would look like a friendly gesture, unless you knew, like I do, that Laney can’t stand Tyler, that she thinks he’s an insufferable dick.

“She is?” Tyler glances from me to Laney uncertainly, like he’s weighing the odds of whether it’d be a more productive use of time to find his mother or to stay here and see if he can convince me to take the stupid ring as some token of his atonement, or whatever he thinks such an exchange would mean.

“Of course she is,” Laney says glibly, drawing him toward the doorway to the dining room. She’s definitely lying; I can tell by the mannered, lofty tilt in her speech. That’s the voice she uses with her father—one that takes extra care to be as articulate and practiced as possible. It’s completely different from her normal tone.

As soon as Laney and Tyler disappear from sight, the woman, whom I still can’t place, starts up her nattering again with renewed vigor. “Tell me, how is the family coping? Oh, your poor mother—”

And just like that, Laney’s back, sans Tyler. She sets a hand on the woman’s elbow, steers her toward the doorway.

“You should go talk to her,” she suggests with a feigned earnestness most Emmy winners can only dream of.

The woman considers. “Do you think?”

“Absolutely. She’d love to see you. In fact, I’ll come with you.”

This is why I love Laney: she always has my back. We’ve been best friends since we were alphabetically seated next to each other in second grade. Scott and Sterling. She’s the coolest person I know; she wears vintage clothes all the time and can quote lines from old fifties-era screwball romantic comedies and just about any rap song by heart, and she doesn’t care what anyone thinks. The best thing about her is that she thinks I’m awesome, too. It’s harder than you think, to find someone who truly believes in your unequivocal, unconditional awesomeness, especially when you’re like me: unspectacular in every way.

As they walk away arm in arm, Laney glances over her shoulder at me, and I shoot her the most grateful look I can manage. She returns it with a strained smile and hurries herself and the woman into the crowded dining room, where I hear muted conversation and the clatter of dinnerware. If I follow, I’ll be mobbed by scores of relatives and acquaintances and total strangers, all pressing to exchange pleasantries and share their condolences. And I’ll have to look them in the eye and say thank you and silently wonder how many of them blame me for not seeing the signs.

“The signs.” It makes it sound like June walked around with the words I Am Going to Kill Myself written over her head in bright buzzing neon. If only. Maybe then—

No. I cut off that train of thought before it can go any further. Another wave of panic rises in my chest, so I lean my hands heavily against the kitchen counter to stop it, press into the edge until it cuts angry red lines into my palms. If I can just get through this hour, this afternoon, this horrible, horrible day, then maybe … maybe I can fall apart then. Later. But not now.

Air. What I need is air. This house, all of these people, they’re suffocating. Before anyone else can come into the kitchen and trap me in another conversation, I slip out the back door leading to the yard and close it behind me as quietly as possible.

I sit down on the porch steps, my black dress tangling around my legs, and drop my head into my hands. I’ve never felt so exhausted in my life, which I suppose isn’t such a shock considering I can’t have slept more than ten hours in the past five days. I close my eyes and take a deep breath, and then another, and then hold the next one until my chest burns so badly I think it might burst.

When I inhale again, I breathe in the humid early-summer air, dirt and dew and—something else. A hint of smoke. My eyes open, and when I turn my head slightly to my left, I see someone, a boy, standing against the side of the house.

Apparently getting a moment to myself just isn’t in the cards today.

I scratch at my itchy calves as I give him a cool onceover. He’s taller than me by a good half a head, and he looks lean and hard. Compact. His messy, light brown hair sticks out in all directions, like he’s hacked at it on his own with a pair of scissors. In the dark. He’s got a lit cigarette in one hand and the other stuck in the front pocket of his baggy black jeans. Unlike every other male I’ve seen today, he’s not wearing a suit—just the jeans and a button-down, sleeves rolled up to his elbows, and a crooked tie in a shade of black that doesn’t quite match his shirt.

I notice his eyes, partly because they’re a startling green, and partly because he’s staring at me intently. He seems familiar, like someone I’ve maybe seen around at school. It’s hard to be sure. All of the faces I’ve seen over the past few days have swirled into an unrecognizable blur.

“So you’re the little sister,” he says. It’s more of a sneer than anything else.

“That would be me.” I watch as he brings the cigarette to his lips. “Can I bum one?”

The request must catch him off guard, because for a few seconds he just blinks at me in surprise, but then he digs into his back pocket and shakes a cigarette out of the pack. He slides it into his mouth and lights it before extending it toward me. When I walk over and take it from him by the tip, I hold it between my index finger and middle finger, like a normal person, while the boy pinches his between his index finger and thumb, the way you would hold a joint. Not that I’ve ever smoked a joint, but I’ve seen enough people do it to know how it’s done.

When I first draw the smoke into my lungs, I cough hard as the boy watches me struggle to breathe. I look away, embarrassed, and inhale on the cigarette a few more times until it goes down smoother.

We smoke in silence, the only sound the scraping of his thumb across the edge of the lighter, flicking the flame on and off, on and off. The boy stares at me, and I stare at his shoes. He has on beat-up Chucks. Who wears sneakers to a wake? There’s writing on them, too, across the white toes, but I can’t read it upside down. He also happens to be standing on what had at one point in time been my mother’s garden. She used to plant daisies every spring, but I can’t remember the last time she’s done that. It’s been years, probably. His shoes only crush overgrown weeds that have sprouted up from the ground.

I meet his eyes again. He still stares; it’s a little unnerving. His gaze is like a vacuum. Intense.

“Do you cut your own hair?” I ask.

He tilts his head to the side. “Talk about your non sequitur.”

“Because it looks like you do,” I continue. He looks at me for a long time, and when I realize he isn’t going to say anything, I take another pull off the cigarette and say, “It looks ridiculous, by the way.”

“Don’t you want to know what I’m doing out here?” He sounds a little confused, and a lot annoyed.

I blow out smoke, watching it float away, and shrug. “Not really.”

The boy’s stare has turned unquestionably into a glare. I’m a little surprised, and weirdly … relieved, or something. It’s better than the pity I’ve seen on people’s faces all day. I don’t know what to do with pity. Pissed off, I can handle. At the same time, I don’t want to be around anyone right now. At all.

I should be inside, comforting my mother. The last time I saw her, she was sitting on the couch, halfway through what had to have been her fourth glass of wine in the past hour. If I was a good daughter, I’d be at her side. But I’m not used to being the good one. That was always June’s role. Mine is to be the disappointment, the one who doesn’t try hard enough and gets in too much trouble and could be something if I only applied myself.

Now I don’t know what I’m supposed to be.

I toe into the garden a little, drop the cigarette butt and scrape dirt over to cover the hole. At this point I have two options: face the throng of people inside, or stay out here. It’s like a no-win coin toss. Option number one won’t be pretty, but I might as well get it over with, since I don’t really want to stand outside being glared at for no reason by some stranger, either. Even if he does share his cigarettes.

“Well, it’s been fun,” I say drlly. “We should do this again sometime. Really.”

I teeter across the uneven yard in my stupid shoes, aware that one misstep will send me sprawling. I’ve got one foot on the porch stairs when he calls out, “Hey,” in a sharp voice.

I turn. The boy steps away from the white siding, out of the garden. He pauses, his mouth open like he’s going to say something more, but then he closes it again like he’s changed his mind and flicks the last inch of his cigarette onto the grass.

“You tore your … leg … thing,” he says.

I bend my leg up to examine it—sure enough, there’s a tear in the tights, running from my ankle to my shin. When I glance back up at him, he’s disappearing around the corner. What the hell? Does he think that makes him, like, an impressive badass or something, having the last word and mysterious exit? Because it doesn’t. It just makes him kind of a jackass.

The back door opens—it’s Laney.

“Harper?” she says, looking confused. “Are you okay?”

“I’m fine,” I say automatically, even though really, nothing could be further from the truth. I smooth my dress down and carefully make my way up the porch steps. “Thanks for rescuing me earlier. I needed that. I was getting a little—” I stop because I don’t really know what word I’m searching for.

Laney shrugs like it was nothing. “Don’t mention it.” She holds something out to me—a covered dish. Of course. Her face is apologetic. “It’s quiche, courtesy of my dear mother.”

Back in the kitchen, I try to rearrange the refrigerator shelves to make space, but despite my valiant efforts, the quiche won’t fit. Eventually I give up and leave it out on the counter. The whole time Laney watches me cautiously, like she’s afraid at any moment I’ll collapse on the kitchen floor in tears. Everyone has been looking at me that way all day. Maybe because I didn’t cry during the memorial service, even when my mother stood at the podium sobbing and sobbing until my aunt Helen gently led her away.

I don’t know what’s wrong with me. June was my sister. I should be a mess right now. Inconsolable. Not walking around, dry-eyed, completely hollow.

“I saw your dad out there,” Laney says. “He looks—”

“Uncomfortable?” I supply.

She makes a strangled sound, something close to a laugh. “I see he left the Tart at home. Thank God for that, right?”

The Tart is Laney’s nickname for my father’s girlfriend. Her actual name is Melinda; she’s ten years younger than he is and waitresses for a catering company. That’s how she met my father—the previous April, she’d worked the big party his accounting firm threw every year to celebrate the end of tax season. The party was held on a riverboat, and during her breaks, they stood out on the deck, talking and joking about the salmon filet. Or so the story goes.

Dad maintains to this day nothing happened between them until after the separation. I have my doubts.

The truth is, I don’t actually hold any personal grudge against Melinda. She’s nice enough, even if her button nose seems too small for her face and she has these moist eyes that make it look like she could cry at any moment, and she wears pastels and high heels all of the time, even when she’s doing some mundane chore like cleaning dishes or folding laundry. And sure, she can’t hold a decent conversation to save her life, but it’s not like I blame her for my family being so screwed up. She just happened to be a catalyst, speeding up the inevitable implosion.

“You look really tired,” Laney says. “I mean, no offense.” She winces. “I’m sorry. That was so the wrong thing to say.”

She says it like there’s a right thing to say. There really, really isn’t.

“I’m just ready to be … done.” I rub at my eyes. “I’m sick of talking.”

“Well, then don’t! Talk anymore, I mean,” she says. “You shouldn’t if you don’t want to. Here, come on. Let’s go upstairs and blow off the circus.”

It’s easy to get from the kitchen to the bottom of the staircase with Laney acting as my buffer, diverting the attention of those who approach with skilled ease and whisking me to the haven of the second floor in a matter of seconds. In the upstairs hallway, there are two framed photos on the wall: the first is of June, her senior portrait, and the second is my school picture from earlier this year. Some people say June and I look alike, but I don’t see much resemblance. We both have the same brown hair, but hers is thicker, wavier, while mine falls flat and straight. Where her eyes are a clear blue, mine are a dim gray. Her features are softer and prettier, more delicate; maybe I’m not ugly, but in comparison I’m nothing remarkable.

There used to be a third picture on the wall, an old family portrait. For their tenth wedding anniversary, my parents rented this giant tent, and they hosted a festive dinner with a buffet and music and all of our family and friends. June and I spent the evening running around with plastic cups, screaming with laughter, making poor attempts to capture fireflies, while my parents danced under the stars to their song—Frank Sinatra’s “The Way You Look Tonight.”

Toward the end of the night, someone gathered the four of us together and took a snapshot. June and I were giggling, heads bent close together, our parents standing above us in an embrace, gazing at each other instead of the camera. It always struck me in the years after how bizarre it was, how two people could look at one another with such tenderness and complete love, and how quickly that could dissolve into nothing but bitterness.

That photo hung on our wall for years and years, staying the same even as June’s and mine were switched out to reflect our progressing ages. Now it’s gone, just an empty space, and June’s will remain the same forever. Only mine will ever change.

I stare at June’s photo and think: This is it. I’ll never see her face again. I’ll never see the little crinkle in her nose when she was lost in thought, or her eyebrows knitting together as she frowned, or the way she’d press her lips together so hard they’d almost disappear while she tried not to laugh at some vulgar joke I’d made, because she didn’t want to let me know she thought it was funny. All I have left are photos of her with this smile, frozen in time. Bright and blinding and happy. A complete lie.

It hurts to look, but I don’t want to stop. I want to soak in everything about my sister. I want to braid it into my DNA, make it part of me. Maybe then I’ll be able to figure out how this happened. How she could do this. People are looking to me for answers, because I’m the one tied the closest to June, by name and blood and memory, and it’s wrong that I’m as clueless as everyone else. I need to know.

“Come on,” says Laney gently, taking my hand and squeezing it, leading me toward my bedroom.

I drag my feet and shake her off. “No. No, wait.”

I veer off toward June’s room. The door is closed; I place my hand on the brass knob and keep it there for a moment. I haven’t been inside since she died. I try thinking back to the last time I was in there, but racing through my memory, I can’t pinpoint it. It seems unfair, the fact that I can’t remember.

Laney stands next to me, shifting from foot to foot. “Harper …”

I ignore her and push the door open. The room looks exactly the same as it always has. Of course it does—what did I expect? Laney flicks on the light and waits.

“It doesn’t feel real,” she says softly. “Does it feel real to you?”

“No.” Six days. It’s already been six days. It’s only been six days. Time is doing weird things, speeding up and slowing down.

June’s room has always been the opposite of mine—mine is constantly messy, dirty clothes and books littering the floor. Hers is meticulously clean. I can’t tell if that’s supposed to mean something. She’d always been organized, her room spotless in comparison to the disaster area that is mine, but I wonder if she’d cleaned it right before, on purpose. Like she didn’t want to leave behind any messes.

Well, she’d left behind plenty of messes. Just not physical ones.

“Do you know what they’re going to do with—with the ashes?” Laney asks.

The lump that’s been lodged in my throat all day grows bigger. The ashes. I can’t believe that’s how we’re referring to her now. Though I guess what was left was never really June. Just a body.

Thinking about the body makes me think about that morning, six days ago in the garage, and I really don’t want that in my head. I look up at Laney and say, “They’re going to split them once my dad picks out his own urn.”

“Seriously?”

“Yeah.”

“That’s—”

“I know.”

Screwed up, is what she wanted to say. It makes my stomach turn, like it did when Aunt Helen decorated the mantel above our fireplace, spread out a deep blue silk scarf, and set up two candleholders and two silver-framed black-and-white photos of June on each side, leaving space for the urn in the middle.

“It should be balanced,” she’d said, hands fisted on her hips, head tipped to the side as she studied her arrangement, like she was scrutinizing a new art piece instead of the vase holding the remains of a once living, breathing person. My sister.

Laney hooks her chin over my shoulder, her arm around my stomach. I don’t really want to be touched, my skin is crawling, but I let her anyway. For her sake.

“There wasn’t a note?” she asks, soft and sad. I shake my head. I don’t know why she’s asking. She already knows.

No note. No nothing. Just my sister, curled in the backseat of her car, an empty bottle of pills in her hand, the motor still running.

I know that because I’m the one who found her.

I slip away from Laney’s grasp. She hasn’t asked me for the details of what happened that morning, and I’m pretty sure she knows the last thing I want to do is talk about it, but I don’t want to give her an opening.

Everything has changed and everything is the same. Everything in this room, anyway. The only addition since June’s death is a few plastic bags placed side by side on the desk, filled with all of the valuables salvaged from her car—a creased notepad, a beaded bracelet with a broken clasp, the fuzzy pink dice that had hung around her rearview mirror. The last bag contains a bunch of pens, a tube of lip gloss and a silver disc. I pick it up to examine it when I notice the desk drawer isn’t shut all of the way.

I draw it open and poke around. There are some papers inside, National Honor Society forms and a discarded photo of her and Tyler that she’d taken off the corner of her dresser mirror and stashed away after their breakup. And on top of everything, a blank envelope. I pull out the letter inside and unfold it. It’s her acceptance to Berkeley, taken from the bulky acceptance package and stored away here for some reason I’ll never know. Tucked in the folds is also a postcard, bent at the edges. The front of it shows a golden beach dotted with beachgoers, strolling along the edge of a calm blue-green sea, above them an endless sky with California written in bubbly cursive.

The only time I ever heard my sister raise her voice with Mom was the fight they had when Mom insisted June accept the full scholarship she’d received to State. Mom said we couldn’t afford the costs. It would’ve been different before the divorce, but there was just no way to fund the tuition now, not when Dad had his own rent to pay, and the money that had been set aside was used to pay their lawyers. Besides, she reasoned, June should stay close to home. There was no reason for her to go all the way across the country when she could get a fine, free-ride education right here.

When June was informed of this, she and Mom had screamed at each other, no-holds-barred, for over an hour, until they were too exhausted to argue anymore and June had finally, in defeat, retreated to her room. She didn’t speak to our mother for an entire week, but she accepted the scholarship and admission to State and never mentioned Berkeley to us again.

I turn the postcard over, and it’s like all of the air has been sucked out of the room.

Laney notices, because she lifts her head and says, “Harper? What is it? Harper.”

I’m too busy staring at the back of the card to answer. Written there are the words, California, I’m coming home, in June’s handwriting. Nothing more.

Laney pulls it from my hands and reads it over and over again, her eyes flitting back and forth. She looks at me. “What do you think it means?”

It could mean nothing. But it could mean something. It was at the top of the drawer, after all. Maybe she meant for it to be found.

California was her dream. She wanted out of this town more than anything. She must have been suffocating, too, and we’d drifted so far apart that I never noticed. I never took it seriously. No one did. And now she’s dead.

“It’s not right,” I say.

Laney frowns. “What’s not right?”

“Everything.” I snatch back the postcard and wave it in the air. “This is what she wanted. Not to be stuck in this house, on display like—like some trophy. She hated it here, didn’t she? I mean, isn’t that why she—”

I can’t finish; I throw the postcard and envelope back into the drawer and slam it shut with more force than necessary, causing the desk to rattle. I am so angry I am shaking with it. It’s an abstract kind of anger, directionless but overwhelming.

Laney folds her arms across her chest and bows her head.

“I don’t know,” she says quietly. “I don’t know.”

“How did things get so bad?” I whisper. Laney doesn’t answer, and I know it’s because she, like me, has no way to make sense of this completely senseless act. Girls like June are not supposed to do this. Girls who have their whole lives ahead of them.

We stand next to each other, my hands still on the drawer handles, when the thought comes to me. It’s just a spark at first, a flicker of a notion.

“We should take her ashes to California.”

I don’t even mean to blurt it out loud, but once it’s out there, it’s out—no taking it back. And as the idea begins to take root in my mind, I decide maybe … maybe that isn’t such a bad thing.

“Harper.” Laney’s using that voice again, that controlled voice, and it makes me want to hit her. She’s not supposed to use that voice. Not on me. “Don’t you think that’s kind of a stretch? Just because of a postcard?”

“It’s not just because of a postcard.”

It’s more than that. It’s about what she wanted for herself but didn’t think she’d ever have, for whatever reason. It’s about how there is so much I didn’t know about my sister, and this is as much as I’ll ever have of her. College acceptance letters and postcards. Reminders of her unfulfilled dreams.

“Your mom would totally flip,” Laney points out, but she sounds more entertained by the prospect than worried. “Not to mention your aunt.”

I don’t want to think about Aunt Helen. She’s just like everyone else downstairs, seeing in June only what they wanted to see—a perfect daughter, perfect friend, perfect student, perfect girl. They’re all grieving over artificial memories, some two-dimensional, idealized version of my sister they’ve built up in their heads because it’s too scary to face reality. That June had something in her that was broken.

And if someone like June—so loving, kind, full of goodness and light and promise—could implode that way, what hope is there for the rest of us?

“Who cares about Aunt Helen?” I snap.

Laney hesitates, but I see something in her eyes change, like a car shifting gears. Like she’s realizing how serious I am about this. “How would we even get there?”

“We can drive. You have a car.” Not much of a car, but more than what I have, which is nothing. Laney’s dad is loaded but has this weird selective code of ethics, where he believes strongly in teaching her the lesson of accountability and made her pay half for her own car, and so after some months of bagging groceries, she’d saved up enough to put half down on a beat-up old Gremlin.

“My Gremlin is on its last leg. Wheel. Whatever. There is no way it’d make it from Michigan to California.”

“Yeah, but still—” I’m growing more convinced by the second. “That’s what she wanted, right? California, the ocean?”

Laney just stares at me, and I wonder if this is how it will be from now on, if I am always going to be looked at like that by everyone, even my best friend.

I don’t care. She can stare at me all day and it won’t change my mind. There were so many things I’d done wrong in my relationship with my sister, but this. I could do this. I owe her that much.

“I’m going to do this,” I tell her. “With you or without you. I’d rather it be with.”

I expect Laney to say, “It would be impossible,” or, “I know you don’t mean it,” or, “Don’t you think you should go lie down?”

Instead, she glances down at the postcard, brow furrowed like if she stares hard enough it’ll reveal something more.

When she looks back up, her mouth has edged into a half smile. “So California, huh? That’s gonna be a long drive.”