Читать книгу Highland Barbarian - Hannah Howell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

Оглавление“A rotting piece of refuse, a slimy, wart-infested toad, a—a—” Cecily frowned and stopped pacing her bedchamber as she tried to think of some more ways to adequately describe the man she was about to be married to, but words failed her.

“M’lady?”

Cecily looked toward where her very young maid peered nervously into the room and she tried to smile. Although Joan entered the room, she did not look very reassured, and Cecily decided her attempt to look pleasant had failed. She was not surprised. She did not feel the least bit pleasant.

“I have come to help ye dress for the start of the celebration,” Joan said as she began to collect the clothes she had obviously been told to dress Cecily in.

Sighing heavily, Cecily removed her robe and allowed the girl to help her dress for the meal in the great hall. She needed to calm herself before she faced her family, all their friends, and her newly betrothed again. Her cousins felt they were doing well by her, arranging an excellent marriage, and by most people’s reckoning, they were. Sir Fergus Ogilvey was a man of power and wealth by all accounts, was not too old, and had gained his knighthood in service to the king. She was the orphaned daughter of a scholar and a Highland woman. She was also a woman of two-and-twenty with unruly red hair, very few curves, and freckles.

She had long been a sore trial to her cousins, repaying their care with embarrassment and disobedience. It was why they were increasingly cold toward her. Cecily had tried, time and time again, to win their love and approval, but she had consistently failed. This was her last chance, and despite her distaste for the man she was soon to marry, she would stiffen her spine and accept him as her husband.

“A pustule on the arse of the devil,” she murmured.

“M’lady?” squeaked Joan.

The way Joan stared at her told Cecily that she had spoken that last unkind thought aloud and she sighed again. A part of her mind had obviously continued to think of more insults to fling at Sir Fergus Ogilvey, and her mouth had unfortunately joined in the game. The very last thing she needed was to have such remarks make their way to her cousins’ ears. She would lose all chance of gaining their affection and approval then.

“My pardon, Joan,” she said, and forced herself to look suitably contrite and just a little embarrassed. “I was practicing the saying of insults when ye entered the room and that one just suddenly occurred to me.”

“Practicing insults? Whate’er for, m’lady?”

“Why, to spit out at an enemy if one should attack. I cannae use a sword or a dagger and I am much too small to put up much of a successful fight, so I thought it might be useful to be able to flay my foe with sharp words.”

Wonderful, Cecily thought as Joan very gently urged her to sit upon a stool so that she could dress her hair, now Joan obviously thought her mistress had gone mad. Perhaps she had. It had to be some sort of lunacy to try unendingly for so many years to win the approval and affection of someone, yet she could not seem to help herself. Each failure to win the approval, the respect, and caring of her guardians seemed to just drive her to try even harder. She felt she owed them so much, yet she continuously failed in all of her attempts to repay them. This time she would not fail.

“Here now, wee Joan, I will do that.”

Cecily felt her dark mood lighten a little when Old Meg hurried into the room. Sharp of tongue though Old Meg was, Cecily had absolutely no doubt that the woman cared for her. Her cousins detested the woman and had almost completely banished her from the manor, although Cecily had never been able to find out why. To have the woman here now, at her time of need, was an unexpected blessing, and Cecily rose to hug the tall, buxom woman.

“’Tis so good to see ye, Old Meg,” Cecily said, not surprised to hear the rasp of choked-back tears in her voice.

Old Meg patted her on the back. “And where else should I be when my wee Cecily is soon to be wed, eh?” She urged Cecily back down onto the stool and smiled at Joan. “Go on, lassie. I will do this. I suspicion ye have a lot of other things ye must see to.”

“I hope ye havenae hurt her feelings,” Cecily murmured as soon as Joan was gone and Old Meg shut the door.

“Nay, poor lass is being worked to the bone, she is, and is glad to be relieved of at least one chore. Your cousins are twisting themselves into knots trying to impress Ogilvey and his kin. They dinnae seem to ken that he is naught but a grasper who thinks himself so high and mighty he wouldst probably look down his long nose at one of God’s angels.”

Cecily laughed briefly, but then frowned. “He does seem to be verra fond of himself.”

Old Meg harrumphed as she began to vigorously brush Cecily’s hair. “He is so full of himself he ought to be gagging. The mon is acting as if he does ye some grand favor by agreeing to wed with ye. Ye come from far better stock than that prancing mongrel.”

“He was knighted in the service of the king,” Cecily felt moved to say even though she felt no real compulsion to defend the man.

“The fool stumbled into the way of a sword that would have struck our king, nay more than that. It wasnae until Ogilvey paused a wee moment in cursing and whining—after he had recovered from his swoon, mind ye—that he realized everyone thought he had done it apurpose. The sly cur did have the wit to play the humble savior of our sire, I will give ye that, although he did a right poor job of it.”

“How do ye ken so much about it?”

“I was there, wasnae I? I was visiting my sister. We were watching all the lairds and the king. Some foolish argument began between a few of the lairds, swords were drawn, and the king nearly walked into one save that Ogilvey was so busy brushing a wee speck of dirt off his cloak he wasnae watching where he was going. Tripped o’er his own feet and stumbled into glory, aye.”

Cecily frowned. “He has only e’er said that he did our king a great service. Verra humble about it all he is.”

“Weel, he cannae tell the truth about it, can he? Nay when he let the mistake stand and got himself knighted and all.”

So she was soon to marry a liar, Cecily thought, and inwardly sighed. That might be an unfair judgment. It could well have been impossible for Sir Fergus to untangle himself from the misconception. After all, who would dare argue with a king? And why was she wearying her mind making excuses for the man, she asked herself.

Because she had to was the answer. This was her last chance to become a part of this family, to be more than a burden and an object of charity. Although she would have to leave to abide in her husband’s home, at least she could leave her cousins thinking well of her and ready to finally consider her a true and helpful part of their family. She would be welcome in their hearts and their home at last. Sir Fergus was not a man she would have chosen for the father of her children, but few women got to choose their husbands. Poor though she felt the choice was, however, she could take comfort in the fact that she had finally done something to please her kinsmen.

“Ye dinnae look to be too happy about this, lass,” said Old Meg as she decorated Cecily’s thick hair with blue ribbons to match her gown.

“I will be,” Cecily murmured.

“And just what does that mean, eh? I will be.”

“It means I will be content in my marriage. And, aye, I shall have to work to be so, but it will suffice. I am nearly two-and-twenty. ’Tis past time I was married and bred a few bairns. I but pray they dinnae get his chin,” she muttered, then grimaced when Old Meg laughed. “That was unkind of me.”

“Mayhap, but ’twas the hard, cold truth. The mon has no chin at all, does he.”

“Nay, I fear not. I have ne’er seen such a weak one. ’Tis as if his neck starts at his mouth.” Cecily shook her head, earning a sharp reprimand from Old Meg.

“If ye dinnae wish to be wed to the fool, why have ye agreed to this?”

“Because Anabel and Edmund want this.”

When Old Meg stepped back to put her hands on her ample hips and scowl at her, Cecily stood up and moved to the looking glass to see if she was presentable. The looking glass was one of the few richer items in her small bedchamber, and if Cecily stood a little to the side, she could see herself quite well despite the large crack in it. She felt that small worm of resentment in her heart twitch over being given only the things Anabel or her daughters no longer wanted or that were marred in some way, but she smothered it. Anabel could have just thrown the cracked looking glass away as she had so much else that had belonged to Cecily’s mother.

Cecily frowned as she realized she would have to plot some way to slyly retrieve a few things from hiding. She glanced toward a still scowling Old Meg. One of the woman’s most often voiced complaints was about how Anabel had tossed away so many of Moira Donaldson’s belongings. It was, perhaps, time to let the woman know that not everything was lost. At first, it had just been a child’s grief that had caused Cecily to retrieve her mother’s things and hide them away. Over the years, it had slowly become a ritual and, she ruefully admitted to herself, a form of rebellion.

The same could be said for her other great secret, she mused, glancing toward the small ornately carved chest holding her ribbons and the meager collection of jewelry allotted to her. Anabel had rapidly claimed all the jewelry that had once been Moira’s, or so the woman believed. Hidden away beneath the ribbons and trinkets in that chest were several rich pieces of jewelry that Cecily refused to give up, pieces her father had given her after her mother had died. He had intended her to have the rest when she grew older, but Cecily had mentioned that to her guardians only once. Anabel’s fury had been chilling. In truth, Cecily suspected it was one reason Anabel made such a display of it when she threw away yet another thing that had once belonged to Cecily’s mother or father. Holding fast to those few pieces of jewelry had been enough to keep Cecily quiet when she saw Anabel or her daughters wearing the jewelry that had once adorned Moira Donaldson.

The woman deserved something for caring for a penniless orphan, Cecily told herself, firmly pushing aside the resentment she could not seem to fully conquer; then she turned to face Old Meg. That woman looked an odd mix of annoyed and concerned. Even though Cecily had taken only a fleeting note of her own appearance, deeming it neat and presentable, she smiled at Old Meg and lightly touched her beribboned hair.

“It looks verra bonnie, Meg,” she said.

Old Meg snorted and crossed her arms. “Ye barely glanced at yourself, lass. Ye got all somber and looked to be verra far away. What were ye thinking on?”

“Ah, weel, a secret I have kept for a verra long time,” Cecily replied, speaking softly as she quickly moved to Old Meg’s side. “Do ye recall my favorite hiding place?”

“Aye,” Old Meg replied, speaking as softly as Cecily was. “In the dungeon. That wee hidden room. I ne’er told anyone, though I should have. Ye could have gotten yourself locked in there and, if I wasnae about, been stuck in there good and tight.”

“Weel, ye were about and I was e’er safe. But heed me, please, for I may yet need your help. I have hidden some things in there, things Anabel threw away, things that Maman and Papa and e’en Colin loved.” She laughed a little when Old Meg hugged her.

“And ye want me to be sure they go with ye when ye marry.”

“Aye.” Cecily pointed to the small chest that hid her other treasures. “And that wee chest.”

Old Meg sighed. “Your da gave ye that. Ye were so pleased with the gift. It has a wee hidey-hole in it, and ye loved to put your special things inside it. What have ye hidden in it now?”

“After Maman died, my father gave me a few pieces of her jewelry. I was to get the rest when I got older, but Anabel,” Cecily ignored Old Meg’s softly muttered and rather crude opinion of Anabel, “kept everything. She said all of Maman’s jewels and other fine things were now hers. So I kept the ones Papa had given me a secret from Anabel. ’Twas wrong of me, I ken it, but—”

“’Tis nay wrong for a child to hold fast to something that reminds her of her parents.”

“That is what I tell myself whene’er I begin to feel guilty.”

“Ye have naught to feel guilty about.”

Cecily gently touched her fingers to Old Meg’s mouth, silencing what she knew could easily become a long rant about how poorly she had been treated by her guardians. “It matters not. Anabel and Edmund are my family, and I have been a sore disappointment to them. This time I mean to please them. Howbeit, I willnae lose what little I have left of my brother, father, and mother. I need ye to ken where I have hidden what few things I could hold tight to.”

Old Meg sighed and nodded. “If ye cannae get them away yourself, I will see that they come to ye.”

“Thank ye, Meggie. ’Twill be a comfort to me to have them close at hand.”

“Ye are really going to marry that chinless fool, arenae ye?”

“Aye, ’tis what they want, and this time I mean to please them. And as I said, I am almost two-and-twenty and have ne’er e’en been wooed. Or properly kissed.” Cecily quickly banished the thought of Sir Fergus kissing her, for it made her feel slightly nauseous. “I want bairns and one needs a husband for that. I am sure it will be fine.”

Old Meg gave her a look that said she was daft, but only muttered, “Let us now pray that those bairns ye want dinnae get that fool’s chin.”

“Weel, at least ye look presentable.”

Cecily smiled faintly at Anabel, deciding to accept those sharp words as a compliment. She forced herself to stop staring at the intricate gold and garnet necklace Anabel wore, one that had been a gift her father had given her mother upon their marriage. It was painful to be reminded of times past, of the love her mother and father had shared, especially when she would soon be married to a man she was not sure she could ever love.

She looked around the great hall, taking careful note of all the people attending the feast. It was the start of two weeks of festivities, which would end with her marriage to Sir Fergus Ogilvey. Cecily knew very few of the people since she had rarely been allowed to join in any feasts or even go with her kinsmen on any visits. She suspected these people came to this wedding celebration to eat, drink, and hunt all at someone else’s expense.

When she finally espied her betrothed, she sighed. He stood with two other men, all three looking very self-important as they talked. Cecily realized she was not even faintly curious about their conversation and suspected that was a very bad omen concerning her future. Surely a wife should be interested in all her husband was interested in, she thought.

As Anabel began to tell her all about each and every guest—who they were, where they were from, and why it was important to cater to their every whim—Cecily tried to find something about her betrothed that she could like or simply appreciate. He was not ugly, but neither was he handsome. He definitely had a very weak chin and a somewhat long, thin nose. His brown hair was rather dull in color, and it already showed signs of retreating from his head. She recalled that he had eyes of a greenish hazel shade, a nice color. Unfortunately, his eyes were rather small, his lashes thin and very short. He had good posture and he dressed well, she decided, and felt relieved that she could find something to compliment him on if the need arose.

“Are ye e’en listening?” hissed Anabel. “This is important. Ye will soon be mixing freely with these people.”

Cecily looked at Anabel and tensed. Something had angered the woman again, and Cecily felt her heart sink into her stomach. She hastily tried to recall something, anything, the woman had just said, only to watch Anabel visibly control her temper. Cecily was surprised to discover that she found that even more alarming. Anabel very clearly wanted this marriage—desperately. Even if she was not determined to do this to please Edmund and Anabel, to try to finally gain some place in this family, Cecily realized there really was no choice for her. If she did not marry Sir Fergus Ogilvey willingly, she would undoubtedly be forced to do it.

“I was looking at Sir Fergus,” Cecily said.

“Ah, aye, a fine figure of a mon. He will do ye proud.”

Cecily very much doubted it but just nodded.

“And I expect ye to be a good wife to the mon. I ken I have told ye this before, but it bears repeating, especially since ye have always shown a tendency to forget things and e’en behave most poorly. A good wife heeds her husband’s commands. ’Tis her duty to please her husband in all things, to be submissive, genteel, and gracious.”

Marriage was going to be a pure torment, Cecily mused.

“Ye must run his household efficiently, keeping all in the best of order. Meals on time and weel prepared, linens clean and fresh, and servants weel trained and obedient.”

That could prove difficult, for Anabel had never trained her to run a household, but Cecily bit the inside of her cheek to stop those words from escaping her mouth. Through punishments and long observation, she actually had a very good idea of what was needed to run a household. In truth, the many punishments she had endured had given her some housekeeping skills she doubted any other fine lady could lay claim to. Cecily inwardly frowned as she glanced at Sir Fergus. Instinct told her that the man was not one who would appreciate such skills, would actually be appalled to discover that his new wife knew how to scrub linens and muck out stalls.

“A good wife tolerates her husband’s weaknesses,” continued Anabel.

Cecily suspected Sir Fergus had a lot of weaknesses, then scolded herself for such unkind thoughts. She would be married to the man soon. It was time to find something good about her betrothed. There had to be something. She had probably just been too busy feeling sorry for herself and convincing herself to meekly accept her fate to notice.

“A good wife ignores her husband’s wanderings, his other women—”

“Other women? What other women?” Cecily was startled into asking. This was a new twist in this oft-repeated lecture that she did not like the sound of at all.

Anabel sighed and rolled her eyes, big blue eyes that she was extremely vain about. “Men are lusty beasts, child. ’Tis their way to rut with any woman who catches their eye. A wife must learn to ignore such things.”

“I dinnae see why she should. Her husband took a vow before God just as she did. ’Tis his duty to honor vows spoken.”

After looking around to make sure they were alone, Anabel grabbed Cecily by the arm and tugged her backward, a little closer to the wall and even farther away from the others gathered in the great hall. “Dinnae be such a fool. Men care naught for such things. They consider it their right to bed whomever they wish to.”

“My father was faithful to my mother.”

“How would ye ken that, eh? Ye were naught but a bairn. Trust me in this, ye will be glad the mon slakes his lust elsewhere and troubles ye with it only rarely. ’Tis a disgusting business that only men get any pleasure out of. Let the peasant lasses deal with it. Since men feel they must have a quiverful of sons, ye will be burdened with the chore of taking him into your bed often enough to heartily welcome such respites.”

“Take him into my bed? Willnae he be sleeping there every night anyway?”

“Where did ye get such a strange idea?”

“My mother and father shared a bed. And, aye, I was just a wee child, but I do ken that.”

“How verra odd,” Anabel murmured, then shrugged. “Probably some strange practice from the Highlands. They are all barbarians up there, ye ken. Ye, however, have been raised amongst civilized people and ’tis past time ye cast aside such thoughts and beliefs.”

Cecily hastily swallowed her instinctive urge to defend her mother’s people. She had learned long ago that it did no good. All such defense accomplished was to anger Anabel and get Cecily sentenced to some menial, exhausting, and often filthy chore as a penance for speaking out. She had the feeling Anabel said such things to her on purpose. At times it almost seemed that Anabel hated the long-dead Moira Donaldson, although Cecily had no idea why the woman should do so or what her sweet mother could have done to earn such enmity. The woman often derided her father as well. Cecily did not understand Anabel’s apparent animosity for her late parents and, sadly, did not think she would ever get Anabel to explain it.

The thought of her lost family brought on a wave of grief and Cecily stared at her feet as she fought back her tears. It would soon be her wedding day, the most important day for a woman, and she was surrounded by strangers and people who did not truly care for her. If Old Meg managed to slip inside the chapel or a few of the gatherings, Cecily would at least know that one person who loved her was close at hand, but she could not be sure Old Meg could do so. If Anabel even glimpsed the woman in the room, she would swiftly send Old Meg away, far away. She knew her family was with her in spirit, in her heart, and in her memories, but she dearly wished she had them at her side.

“Will ye smile?” hissed Anabel. “Wheesht, ye look ready to weep. Best not let Sir Fergus catch that look upon your face. He will think ye arenae pleased to have him as your husband.”

There was a tone to Anabel’s voice that told Cecily that that was the very last thing the woman wanted. If it happened, punishment would be swift and harsh. Although Cecily doubted she could produce a credible smile, she did her best to hide her sorrow. When she felt she had accomplished that, she looked at Anabel, only to find the woman was gaping at the doorway to the great hall. A quick glance around revealed that everyone else was doing the same thing, and Cecily became sharply aware of how quiet it had become in the hall.

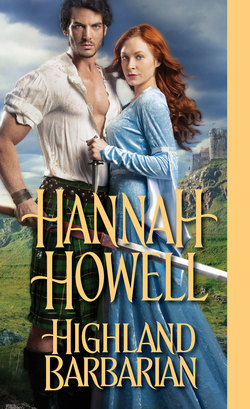

Although the sight of so many silent, wide-eyed, open-mouthed people was fascinating, curiosity forced Cecily to look toward the doorway of the great hall as well. It was only a sudden attack of pride that kept her from mimicking the others when she saw the man standing there. He was very tall and leanly muscular. His long black hair hung down past his broad shoulders, a thin braid on either side of his stunningly handsome face. He wore a plaid, the dark green crossed with black and yellow lines. He also wore deerskin boots and a white linen shirt, both dusty from travel. From behind his head she could see the hilt of a broadsword. He wore another sword at his side, and she could see a dagger sheathed inside his left boot.

Cecily was rather glad she had not been in the midst of a hearty defense of Highlanders at that precise moment. This man did look gloriously barbaric. That appearance was only enhanced by what he held. Grasped by the front of their jupons and dangling several inches off the floor, the Highlander held two of her cousins’ men-at-arms. The men did not seem to be struggling much, she thought with a touch of amusement, nor did their captor seem overly burdened by the weight he held in each hand. Deciding that someone had to do something, Cecily took a deep breath to steady herself and began to walk toward the man.