Читать книгу P. C. Chang and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Hans Ingvar Roth - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

A very special artwork adorns the platform walls of the subway station at Stockholm University. Look carefully and you will find in it all thirty articles of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Strikingly, all are reproduced in uniform capitals and without spaces between words or periods at the end of the sentences. They include the right to life, liberty, and security of person; the right not to be held in slavery or subjected to torture; the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; as well as the right to an adequate standard of living (Articles 3, 4, 5, 18, 25). The artwork also illustrates the central idea behind this important statement of rights. It is, above all, a matter of a whole, or an assembly, of human rights, none of which can be separated from each other. Each of its articles plays an important role in contributing to that unity which might be described as the declaration’s overarching function: to promote respect for the inviolable dignity of every human being.

The artwork has its origins in an art project by the French-Belgian artist Françoise Schein titled To Write the Human Rights, or, alternatively, TO INSCRIBE the Human Rights. There is an equivalent mural in the Paris Metro station of Concorde. Realized by the organization INSCRIRE, this global art project is just one of many instances that illustrate the fact that the UN Declaration is one of the most widely disseminated and best-known documents in the world today. (I will use the expressions the UN Declaration, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UDHR as equivalent in the following text.)

As a student, I used occasionally to stop and look at the articles, wondering about their meaning. Later on, I was fortunate enough to be able to work as a researcher and teacher with a specialist interest in human rights. Initially, I did not think about the individuals involved in drafting the declaration, with the exception of Eleanor Roosevelt, the distinguished chair of the Commission on Human Rights. My interest in this aspect has deepened over the years, however, with my attention becoming increasingly drawn toward the principal authors of this document. While the drafters of the founding documents of the United States are very well known persons all around the world, the drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are not so famous (with the exception of Eleanor Roosevelt).

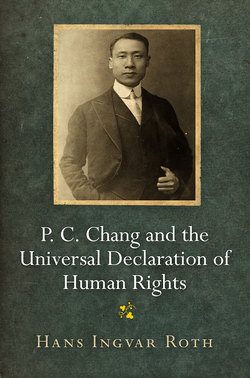

One person has emerged as particularly fascinating with respect to the core elements of the Universal Declaration: the Chinese philosopher, pedagogue, and diplomat Peng Chun Chang. When I began this writing project several years ago, I discovered to my surprise that very little had been written about Peng Chun Chang and his contribution to the UN Declaration. Despite the appearance in recent years of growing numbers of articles on Chang and his involvement as coauthor of the declaration, the scholarship on him remains relatively slight and includes no critical study or biography dedicated to Chang specifically. The present book is an attempt to fill that gap.

A number of people have provided me with inspiration, information, and valuable input during the writing process. I wish to offer special thanks to Stanley (Yuan Feng), son of Peng Chun Chang, without whose kind assistance this book would not have been possible. I should also like to acknowledge the generosity of Habib Malik, Willard J. Peterson, Harald Runblom, Göran Möller, Sven Hartman, Göran Collste, Mary Ann Glendon, Torgny Wadensjö, Torbjörn Lodén, Ove Bring, Jenny White, Pierre Etienne Will, Yi-Ting Chen, Magnus von Platen, Hans Ruin, Alex Trotter, and Gunnar and Hongbin Henriksson. My thanks go also to the participants at the research seminars at CASS (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Nankai University, which I joined during a visit to China in March 2017, as well as to my audience at the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights in February 2017. I am also grateful for helpful discussions on the philosophy of human rights with James Griffin, David Miller, and John Tasioulas through the years. For granting me research leave I am grateful to Paul Levin and Stockholm University’s Institute for Turkish Studies. I am also indebted to Lily R. Palladino, my editor at Penn Press who did an excellent job with my manuscript. Last but not least, a big thank you to Birgit och Sven Håkan Ohlssons Foundation for a translation subsidy, and to my translator, Stephen Donovan. To one and all, my deepest thanks!