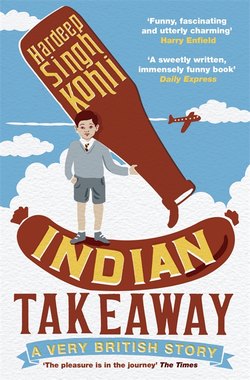

Читать книгу Indian Takeaway - Hardeep Singh Kohli - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE DO YOU COME FROM … ORIGINALLY?

ОглавлениеHome.

The most innocuous and yet the most complex of words. Both comforting and confusing.

I grew up on an estate in the north of Glasgow, a place called Bishopbriggs. It was a slightly over-planned sixties-built concept estate; basically a load of Wimpey houses on a few fancy little streets with slightly avant-garde names like Endrick Bank, Lyne Croft and Bowmont Hill.

It was down Bowmont Hill that my idyllic childhood collided with Glaswegian reality. It was the height of the summer holidays and all the kids on the estate ended up playing together in the street. The craze that summer was for home-made ice lollies. It seemed every freezer in every house contained moulds filled with any variety of frozen concoction. The kids would pile back to each other’s houses to try the latest home-made blend. I recall being rather taken with a milk and Coke version. Then, one day, we ended up heading into the garden of some random child. There must have been eleven or twelve of us. We were met at the garden gate by his mum who allowed every child in, every child with the exception of me. She looked at me rather pointedly.

‘Youse can all come in … but not him … ’

It was clear that I was not welcome. I stood on the pavement, numb, watching the backs of my friends as they disappeared into the garden and left me on my own.

I had no idea why I had been singled out, and ran home crying. But my mum knew exactly why I had been ostracised.

‘Don’t worry,’ she told me. ‘This is life; what can you do? It is not our job to rock the boat.’

It was clear that she felt that we were visitors in another man’s country. Well, maybe she felt like a visitor, but I was born in this country. I felt compelled to rock as many boats as they would let me board. I had no knowledge of anywhere else, of anytime else. Glasgow in 1974 was the beginning, middle and end of my reality.

I can’t say I have ever forgotten that feeling of standing alone on Bowmont Hill. Those are the sorts of experiences that never soften with time; they stay with you; you replay them in your head so that the next time it happens, you will be better prepared. Unfortunately, there was no shortage of next times.

As I got older I would be asked time and again where home was and they would laugh when I suggested Glasgow. ‘Where do you come from?’ they would ask, adding: ‘Originally,’ if I was glib enough to suggest the Great Western Road. Implicit in all of their interrogations was the accusation that I did not belong, that I was other, that my home was not here. To them I could never be Scottish.

Yet neither did I feel particularly Indian. Of course, I was born to Indian parents and grew up in an Indian house. But that Indian house was always somewhere in Glasgow. It was all very confusing.

As a young child my sense of self was a cultural car crash, a collision between the values of my parents and the ridicule of the playground. In those days it was commonplace for my brothers and me to be referred to as ‘chocolate drops’, which I preferred to the more casually vicious ‘darkie’. (Perhaps this is why I have never been a great fan of chocolate drops.) The perception of India was that all Indians were smelly, smelling, presumably, of curry. The fact that Britain later adopted Indian food as its own was an irony lost on Charlie McTeer, the celebrated school thug, as he spent the entire day with a clothes peg on his nose, complaining of the aroma that apparently emanated from my body. I have to confess to having been unaware of any smell, other than my mum’s spittle from where she had invariably cleaned some breakfast off my face.

Yet, this idea of India was radically different from the place I watched on TV or saw splashed across the newspapers. The Indians I saw on TV were either starving or poor or both; cyclone-hit Bangladeshis, emaciated and barely alive. Surely this was not where I fitted in?

As I grew older, perceptions of India changed. I became aware of the more spiritual side of India through the Beatles and their beads and cheesecloth, and their discovery of their guru, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. I remember being faintly embarrassed by the idea of this bearded Svengali owning a legion of Rolls Royces in a country which was in the throes of famine and pestilence. The India of the early 1980s was a world away from the economic superpower it is today. I didn’t understand how, to the young, free-minded, drug-addled youth, India was a place worth visiting. India was the home of mysticism, the epicentre of spirituality, the birthplace of religious civilisation. But I found it impossible to access any of the cool associated with that world. Lank-haired hippies would trail their way across three continents to find themselves in the warm waters of the Arabian Sea in Goa. I never quite grasped how this worked, or what they did once they found themselves. What did anyone hope to find in India that wasn’t already present in their Scottish life? I had spent most of my childhood being ridiculed for being Indian and yet here were these white folk off to the selfsame country to find enlightenment.

And then there was the Kama Sutra. Why did the Kama Sutra have to be Indian? The idea of an ancient book all about sex – with drawings – could not have been further from my experience of India. In my house I never saw my parents kiss, and still never have. My mum gets a hug once a year on her birthday and a sideways hug at that, lest there be any intimacy. I would be appalled if my mother or father ever used the word ‘love’ in relation to each other. I know they love each other; they have been together for over forty years and have slowly, through the attrition of time, moulded each other into shapes that fit together; much like pebbles on the seashore.

But then again, my India was just a version of India as defined through a childhood in Glasgow. Sunday was our day to be Indian. After a week of mundane Scottish life, my mother would wrangle her three sons into smart clothes and assault us with a damp facecloth before tramping us off with our dad to experience the delights of the gurdwara, the Sikh temple. I never understood why we had to be smartly dressed to visit the temple. If, as my mother so very often told me, God (who was omnipotent and omniscient and all other words beginning with omni-) judged who we were rather than how we appeared, then why did we need to ensure that our trousers were freshly pressed and our shirts free of ketchup? This philosophical musing of an eight-year-old was often met with the counter-argument of a skelp across the back of the thighs.

Temple was great. The religious component of praying and being holy was simply one of a myriad of activities that took place in what was no more than a rundown, near-derelict house on Nithsdale Drive in the Southside of Glasgow. As kids we mostly ran around at breakneck speed in our ironed trousers and ketchup-free shirts, trying our best to crumple our trousers and mark our shirts with ketchup. Gurdwara was where the entire community gathered; it was our parents’ single chance to re-engage with Sikhism and Sikh people. It must have been a blessed relief for them to feel relaxed amongst their ‘ain folk’, for at least one day of the week. When I think about the hard time I used to get as a small brown boy in Glasgow, I forget that my parents had to deal with yet more abuse in a more sinister, less forgiving adult world.

There were two good things about gurdwara, apart from the fact that about a hundred kids were at liberty to play and laugh and generally have a great time. At the end of the religious service, after the hordes had prayed collectively, the holy men would wander amongst the congregation who were sat cross-legged on the floor, handing out prasad. Prasad is a truly amazing thing. If you ever needed convincing that the universe has some form of higher power at its helm, then prasad would be the single substance to convert you. It’s a semolina-and sugar-based concoction bound together with ghee. It is bereft of any nutritional value, but it is hot and sweet and lovely. And it’s holy. What more could you want?

After prasad the congregation would filter downstairs to enjoy langar. I believe the Sikh religion to be the grooviest, most forward thinking of all world religions. Obviously, I have a vested interest, but given the fact that as an organised belief system Sikhism is little over 300 years old, one begins to understand the antecedents of its grooviness. It is a young, vibrant religion that is not bogged down with ancient scripture and dogma. Sikhs were able to experience the other great religions of the subcontinent and construct a new belief system that accentuated positives whilst attempting to eradicate the negatives. And no more is this innovation exemplified than with the beautifully egalitarian concept of langar. Every temple is compelled to offer any comer a free hot meal. In India this happens on a daily basis, but when I was growing up in Glasgow, Sunday was the day of the largest communion. You can be the wealthiest man in Punjab or the lowliest cowherd, but together you sit and share the same modest yet delicious meal, cooked in the temple by devotees. This is langar. It’s a practical manifestation of the theological notion that all are equal in the eyes of God. A tenet at the very heart of Sikhism. And it happens with food. I was meant to be born a Sikh: generosity and food, my two favourite things.

Our bellies full of langar, we would drive a few miles from the temple into the centre of Glasgow, to the Odeon on Renfield Street. In the seventies and early eighties, cinemas were closed on Sundays, a fact utilised by the Indian community the length and breadth of Britain. For six days of the week, cinemas were bastions of British and American film, but on Sunday the sweeping strings and sensuous sari blouses of Bollywood took over. And it felt like every brown person in Glasgow was there. From three o’clock in the afternoon we had a double bill of beautiful women dancing for handsome moustachioed men; of gun fights and fist fights; of love and betrayal. These films were in Hindi, a language lost on us boys; we barely spoke any Punjabi. But the images were bold and strong and most importantly Indian. And guess what? There was also food involved. Hot mince and pea samosas were handed round and occasionally the cinema would fill with the sound of old men blowing cooling air into their hot triangular snacks. Pakoras would be illicitly eaten with spicy chutney. There would be the inevitable spillage and some fruity Punjabi cursing, involving an adult blaming the nearest innocent kid for their own inability to pour cardamom tea from a thermos whilst balancing an onion bhaji on their knee. It was only some years later that I discovered that the eating of food within the cinema was banned.

Not content with a morning of running around the temple, we spent most of the afternoon and early evening running around the cinema; there’s something quite exhilarating about sprinting in the dark while a woman in a skimpy sari is caught in a monsoon shower. The single unifying factor between the Bollywood blockbusters and Glasgow was that it seemed to rain incessantly in both places; but for very different reasons.

My sense of being Indian was further embellished by my gran, the late Sushil Kaur. She came over from India some years after my grandfather passed away, staying with her first born, my dad. I had a special relationship with Gran; I was her favourite. I’d like to think that, of all her grandsons, she selected me because I have the most vibrant personality, that I am the most entertaining and loving of her tribe, the child in whose eyes she saw herself. I’d like to think that. The reality was, however, that I had the warmest body and she felt the cold of Glasgow. There is no medical or anatomical explanation for my higher than average body warmth. It was something I was born with, like my oversized posterior.

Many people have sentimental memories of their gran; baking cakes together, going for fish and chips, or being allowed to stay up that extra bit later. My gran was different. Very different. She was a matriarch, a survivor, a strong woman who had held a family together for years. She loved her family, and she looked after us. My gran played a very big part in my growing up. With two working parents, she was the one who was always there. She taught me Punjabi since she spoke very little English, and in return I taught her English to enable her to teach me more Punjabi. It was beautifully symbiotic. But we all believed that as an uneducated woman from the heart of the Punjab it might be one struggle too many for her to learn the complex and challenging language of English. That was until we overheard her gossiping with Grace Buchanan from next door. She was very good at that; if gossiping had been an Olympic sport she might well have been approached to captain the Indian team. That was my gran.

She would tell us stories of India, of politics and of family. We cooked together, she taught me to sew, and every morning she would wake up and make us all a cup of tea. She would do this thing of adding half a teaspoon of sugar to the pot to encourage it to brew. I abhorred tea with sugar and would always moan the way only a grandson can moan at a grandmother when drinking her tea but, from her lack of response she was clearly used to dealing with complaints. I can still see her now, squatting over a tea tray in our house in Bishopbriggs, stirring the slightly sweetened, discernibly stronger tea.

This was my sense of Indianness: at home with Mum and Dad, temple and Bollywood movies, aunts and uncles, and Gran and her stories. I’m not sure that my day-today experience of being Indian in Glasgow was any more accurate than the image I was offered from the wider culture around me; I had yet to actually visit the sprawling subcontinent. The India I was imbibing at the tender age of nine was an India fed to me by parents still stuck in 1960’s India. All of which was topped up with dislocated images on the silver screen, weekly visits to the Sikh temple, my grandmother and her slightly sweetened tea.

When I eventually got to India in January 1978 for my uncle’s wedding, the country I saw was contained within my grandfather’s house, my uncle’s farm, the streets of the city my father grew up in. It was rural Punjab: ox-drawn carts, old-fashioned trains, squat toilets, rundown towns. I saw very little of the real India, south to north, east to west. And in the years that followed I could never travel all the way to India and not visit my family; that was unconscionable and also restricting. Therefore, I’d never had the chance to explore this place I felt such a deep affinity with whilst simultaneously experiencing a sense of estrangement.

Now, my outward appearance may be Indian but my mind, my heart and my stomach are very much from Glasgow. English is my first language, by quite some way. I can get by with the Punjabi my grandmother taught me but my Hindi is more from movies than from commerce or poetry. Yet, as a turbaned Sikh, Indians expect me to be a fluent Hindi and/or Punjabi speaker. It seems wherever I go in the world the expectation of who I might be is never in sync with who I actually am.

Perhaps this is what I was searching for in India – the secret formula to reconcile the expectations of those around me with the reality. Or maybe it was something much more profound: maybe I had to manage my own confusion, my own expectation. To make some sense of the life I had led thus far, I needed to know why my father had left India, uprooted and had a family in Britain.

There is no better time to ask my dad searching questions about life, the universe and everything than when he has a freshly made mug of tea in his hand and a plate of biscuits on standby. He is captive. (The fact that I had to wait till my mid-thirties to ask such questions is another matter.)

‘Why did you leave India, Dad?’ I asked, more in hope than expectation.

‘To better myself. For a better life for you,’ he replied.

‘But you didn’t even know you were going to have a family when you left.’

‘We didn’t ask so many questions in those days, son.’ He sipped his tea. ‘Life was much easier then. Why are you asking all these questions?’

‘It’s difficult to explain, Dad. I feel like something is missing in my life. A reason for being.’ I looked at him.

‘If you think something is missing, then you should try and find it.’ He finished his tea and looked straight at me. ‘Son … ’

I leaned in. I could sense from the pregnancy of the pause that he was about to offer some insight, some revelation.

‘Did you sign those documents?’

I should explain that my dad runs a property business and is forever sending me documents to sign. Property businesses are built not of bricks and mortar but on documents, battalions, legions, armies of papers, all officially sanctioned and in my dad’s case, invariably requiring my signature. I never seem to manage to sign them correctly or at the right time. As I searched high and low for this latest clutch, I realised that they weren’t the only thing missing. I was thirty-seven years old, the same age my father was when I was born, and I had no idea who I was. My father left the country of his birth and travelled halfway around the planet to set up a new life. What had I done with my life? Maybe the hippies were onto something. Perhaps it was time to start looking for myself, to start making sense of my upbringing, to make sense of me.

‘Dad, I’ve got a plan. I’m going to India.’

‘Good.’ He was always happy when I travelled. ‘Work or pleasure?’

‘I’m going to travel to India to find myself.’ I felt triumphant. It was clear what I had to do.

‘Find yourself?’ he asked. ‘Where did you lose yourself?’ He laughed, heartily and happily.

It was time to go home.

Wherever home might be.

What You Need To Know About My Dad:

I knew that my father would want me to make the journey. He had always been obsessed with travel, his feet never stopped itching. This desire to travel was perhaps foreshadowed in his first job. When he was twenty-four he left Ferozepure, the town of his birth in Punjab, to become a customs officer in Delhi. It was 1959, ten years before I was born. He had trained for a short while in Amritsar, the spiritual capital of the Sikh religion. For a young, single man the bright lights of the big city couldn’t have been more different from the almost medieval squalor of Ferozepure. In Delhi he spent five years living the quintessential bachelor life with his best friend, a man we have come to know as Kapoor Uncle. But Delhi was not the real destination; it was but a stop on the way. America beckoned my father. Her silky whispers travelled halfway across the world to entice him. His plan was to come to London, make some money, research opportunities in America and then take himself over there, to a brave new world.

One absolutely charming thing about my father is that if you ask him where he intended to settle in the States, he has absolutely no idea. His thesis was simple: he was going there to make money; it was thought at that time (and borne out) that there was more money to be made in America than anywhere else, that dreams came true, and my father had dreams. He was so brave to travel halfway across the world not knowing where he’d end up and with no one there to help him.

My father met my mother shortly before they got married. When I say ‘shortly’ I mean about twenty minutes or so before the ceremony itself. That was the beauty of the arranged marriage. My mother was part of the East African diaspora. My grandfather had worked on the railways in India and had been taken over to Nairobi by the British to build more railways. That’s what the British gave their colonies: railways and paperwork. My mum, her two sisters and her brother were brought up as Kenyan Indians. My maternal grandmother died when she was very young; my mother was raised by her elder sister, Malkit, my Massi.

My father is six foot two, my mother is five foot two: that is the least of their differences. They are testament to the success of the arranged marriage system. On paper they have very little in common, no shared interests – she was working-class immigrant Indian, my father was lower middle class from the heart of the Punjab – yet somehow, forty or so years later, they are still very much together. My dad never laughs as much as when my mum is telling a story. His eyes fill with tears and he coughs and splutters with joy.

Soon after their marriage, midway through the swinging sixties, my parents made their way to London, where my mum had family. We lived with my Malkit Massi. I say we, although neither my elder brother Raj, myself nor Sanjeev were around. My mother fell pregnant with Raj in 1965, which is what stopped my father’s plans for his stateside domination. Raj was born shortly after England lifted the World Cup and I followed three years later. The following year Sanjeev popped out and my mother found herself in a house full of men.

This is where the story becomes interesting. I believe that if we had stayed in London and become another of those Hounslow Indian families, we would have all led fairly unremarkable lives. But my father had discovered Scotland after a stint training to be a teacher in Dundee, which gave him a plan B for when he’d had enough of my mum’s family, which he most certainly had by 1972. We piled into our spearmint green Vauxhall Viva and drove the eight hours to Glasgow. I remember with vivid clarity driving down the Great Western Road for the very first time. It was predictably wet but the night was twinkling.

That was my father’s story. So it was no surprise that he liked the idea of his son travelling around India. I wanted to travel the country on my own and discover it for myself, starting at the southernmost tip and travelling north via some prominent and pertinent places. I would cook in each city, town or village and discover a little of India and hopefully a lot of myself. I would complete my journey in Ferozepure at my grandfather’s house, the place of my father’s birth.

My father seemed equally excited about my journey. Having travelled extensively round India, he spoke unpunctuated about all the possible places I could go, all the sights I might see, all the people I might meet. He regaled me with stories of Ladakh, villages on the Pakistan border he once visited as a child, a house he had seen in a magazine once, set on a clifftop near Bombay.

‘Dad, calm down,’ I said. ‘It’s still very much in the early stages.’

‘You have to go to Kashmir. You have to.’ He was insistent. ‘I have a friend in Simla, he will be more than happy to look after you. And Manore Uncle will sort your flights and trains.’ He was planning my entire trip in his head.

‘You seem happy that I’m going,’ I said.

‘Why not?’

He was happy.

Very happy. As if he was going himself.

And maybe he was.

What You Need To Know About My Mum:

My mother is an amazing cook. I have rarely tasted Punjabi food better than that lovingly prepared by my mum. So good is my mother’s food that I have stopped cooking Indian food myself, knowing that I will never come close to her standard. My lamb curry will never have that melt-in-the-mouth consistency, the sauce will never be as well spiced and rich, my potatoes never as floury and soft. My daal will be bereft of that buttery richness, that earthy appeal that warms you from inside. My parathas will never be as flaky and delicious and comforting.

Not only did she cook, clean and prepare four men (my father and her three sons) for the world, she also worked. And how she worked. Our wee newspaper shop on Sinclair Drive in the Southside of Glasgow was like a jail for my mother. While she counted down the days of her sentence, my brothers and I learnt Latin and literature, maths and music, all paid for by the money she garnered from her seven-day-a-week, twelve-hour-a-day existence. Luckily her resolve was harder than the concrete floor she had to stand on. Later in life she had both her knees replaced, no doubt a consequence of that concrete floor and the unforgiving workload. And while she worked, uncomplaining year after year, giving us everything an education can provide for the children of immigrants, she was systematically taking years off her life. Ironically we, her progeny, the very objects of her sacrifice, became strangers to her, educated away from the loving mother that gave life to us.

There is a place in Southall, in the Sikh ghetto west of London, where the food, whilst not quite achieving the heady standards of my mum’s, comes pretty close. In fact it’s the only Indian restaurant I will ever take my parents to in Britain. The food is delicious and it’s like eating at home. Sagoo and Thakar, renamed now as the New Asian Tandoori Centre, is my home from home.

I have often been known to pile my family into the car and drive forty-five minutes to devour their food. They seldom complained, knowing what was coming. (Whenever I go there I am reminded of my parents.) One such day when I was planning my trip to India I realised that so much of contemporary Britain is based around Indian food. There I was in Sagoo and Thakar, a place originally designed to feed immigrants from the Punjab who had come to drive the buses, sweep the streets and staff Heathrow airport, and the joint was full of every sort of person: black, white and everything in between joining the massed ranks of Indians. The common theme seemed to be that we were all British. Food unites. That much is clear. And as I sat there, a devoured plate of lamb curry in front of me and the remnants of a paratha, I started to think that maybe I should return to India what India has so successfully given Britain: food. If I was to find myself in India, I must take some of myself with me. And what better to take than my love of food and cooking? I resolved to take British food to India.

I have always thought that my ability to cook allows me to share a little of my soul with my guests. My parents always instilled in me the generosity of entertaining. No one was ever turned away from our house unfed or unwatered. The breaking of bread breaks down barriers. Food soothes and assuages. Romance is continued over breakfast. Friendships are made over lunch, enmities resolved over dinner. That is the power of food.

In my repertoire I have a number of powerful classic British dishes. This is food to fall in love over, food to fight over, food that I hope will make me friends across a subcontinent. My shepherd’s pie is well practised and relatively unique in that I use nuggets of lamb rather than mince. It’s an innovation I am quietly proud of. I have perfected the art of roasting lamb, beef, pork and chicken. Obviously, I will have to be canny about where I cook pork in India, and given the Hindu majority, I will rule out any beef-based dishes entirely. I have been known to work my culinary magic on fish and shellfish and I am no stranger to vegetable accompaniments, if a little bemused by fully vegetarian meals.

Then I mentioned my idea to my dad… Now, my dad really likes my cooking. He calls me Masterchef and whenever I’m at home in Glasgow he turns up with some exotic shellfish or a special cut of meat or baby quail and expects me to do something amazing with it.

‘Look at this cheeky onion. Can you do anything with it?’ he asked once, brandishing a banana shallot in one hand. From the other hand he produced a clutch of razor clams. ‘And what about these buggers? They’re not very clever. You know what to do with them… And I need you to sign some documents.’

I love his belief in me. However, he was less than impressed by my new plan.

‘So, Dad, I’m going to cook British food in India when I am travelling.’

Silence on the Glasgow end of the phone.

‘Dad?’

‘What?’

‘I said that when I am in India I am going to cook British food.’

Pause. ‘Why?’

‘I just thought that it would be a good idea … you know … to take back to India what India has given Britain … ’

He pauses. Again. ‘Son, if British food was all that good then there would be no Indian restaurants in Britain.’

My father’s logic seemed watertight …

‘Would there?’ he persisted.

‘And did you sign those documents?’