Читать книгу This Finer Shadow - Harlan Cozad McIntosh - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER IV

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

Martin had lived in the Bowery a week before he realized that the sounds and odors seemed less offensive to him; that his acquaintances and his surroundings appeared less brutal. Each night in the hotel some man died loudly in his bed. It was an incident. Martin felt himself in a husk through which no poison could penetrate. One day, in an effort to regain his lost perception he left the street, crossed old Italian town, passed barren, rock-like buildings and looked for the first time at Washington Square. He walked across the park, holding it all—the grassy air, the fat babies, the old men with tanned, bald heads and individualities he’d never seen before nor understood. On one bench he saw several of his comrades on Relief. They were sitting quietly in the warm, fall sunshine. “Talked out,” thought Martin, “and glad of it.” He passed them, nodded, smiled and wondered why they thought him so apart, youthfully looking at them for an answer instead of at himself. He then crossed over to the circular pool in the center of the Square where boys and girls were romping in the thin spray of the fountain. In the anticipation of the approaching colder weather when the water would be stopped and this late play ended for a time, they seemed more active than usual. “Why is it,” Martin asked himself, “that I feel kinship among the antitheses—these gay children or the devil!”

One child, like all the others but for thinner legs and an abundance of pale freckles, looked up at him and asked if he would watch her shoes and stockings while she waded. This responsibility was heartening; and he sat down on the edge of the pool while she went in rather cautiously. The child seemed even more fragile among the vigorous ones who were shoving each other and kicking up the water. For a long time Martin watched her. “She might have been my own little daughter,” he said aloud at last; and immediately the mist seemed to fall more heavily from the fountain and the play to become more violent until he wished it over with. The thought of home—a child—serenities attendant, brought the conflicting inquiries of his life more sharply before him and he brooded. A few drops of cold water in his face stopped the course of these reflections and he looked up frowning, his eyebrows raised. It was the little girl. She was laughing at his discomposure.

“You looked funny,” she said.

“Did I?”

“Yes. That’s why I threw the water. You looked cross. Did I keep you too long?”

“Not at all,” he answered, smiling at her. “You know quite well that wasn’t it at all. Furthermore, I shouldn’t be astonished if you did know, right now, why I was cranky.”

This amused her again.

“You’re the funniest person I ever knew,” she said. “You talk like a teacher.”

“I’m not a teacher; I’m a pupil,” Martin replied. “And I’m funny because I study funny things.”

“What kind of funny things?” asked the child, looking excited.

“Many things. I study lady tigers that take off their stripes every night and put them on in the morning quite differently and——”

“Why do they do that?” interrupted the girl.

“So they will be in style,” he continued seriously. “And I study dentist birds that repair alligators’ teeth; and mice that fly upside down.”

“Why!” exclaimed the girl somewhat indignantly, “I never heard such stories in my life!”

“That isn’t half,” said Martin. “Be very quiet now. Don’t move. Do you see that fly that lit on my knee? He’s looking for something to eat. There. He’s found it. Maybe I spilled sugar on my pants this morning. But do you see what he’s doing before he eats? He’s washing his face with his forelegs.”

The little girl watched carefully and saw the insect dip its head and bring its arms across its face like a brush. Suddenly she waved at it and the fly spun away.

“I can’t stand them,” she said.

“Just the same,” Martin nodded, “it washed its face.”

“It isn’t as funny as the tiger,” the girl concluded. “Tell me how a tiger can take off its stripes. Does it hurt?”

“Of course not.” Martin stood up. “I have to go now.”

The little girl put on her shoes.

“I wish you’d come again to-morrow. If you do, I’ll bring my ball.”

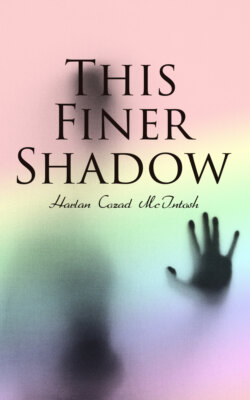

“That will be fun,” called Martin as he walked away. Going back to his hotel he thought of this blue-eyed youngster and how great it would be to tell her fairy tales every night and buy her sandals and her frocks. And with this picture came once more the vision of all the rest of it—a wife’s head on his shoulder, a fireplace, and yes—a pipe. He wondered then where in the world a finer shadow was leading him—a search for mysteries without substance or reason. At that moment he was a tired and a lonely man, quite willing to exchange a pound of mysticism and ideals, hard-won from depth to depth, for one ounce of level complacency. But after the first bitterness had worn off he was the same desperate young lover of the physiostatic tides of force that subtly pull and push until out of sheer pity they permit the frail skeleton to slip up on the sands of its desire where the hollow star, so followed, lies desolate and discontent.

The next day he was glad to see the child again. Her good humor freed him—was pure liberation from the constriction of the Bowery. She called out to him at once.

“Hello, teacher.”

“I’d rather you said ‘Martin.’”

“Is that your first name?”

“Yes.”

“And you don’t mind if I call you that?”

“Of course not.”

“Well,” she said deliberately, “my name is Alice.”

“A pretty name.” Martin appeared abstracted.

“I don’t like it. But I can’t help it. I’d rather be called ‘Betty.’” She held out her hand. “Here’s my ball. Let’s play by the Arch.”

They bounced it back and forth until Alice was tired.

“You can’t throw it on top,” she declared, sitting down on the curb.

Martin examined the light and badly worn tennis ball and measured the distance to the top of the great Arch.

“You’re probably right,” he agreed. But he gave a mighty heave and the ball just rolled over the edge where it remained. This amused Alice; but Martin was annoyed. He stood looking up at the top ledge of the Arch for several minutes. At last, however, he said, “Come along,” for he remembered a drug store near by in which he had seen some tennis racquets.

A policeman had been watching them play ball and Martin thought the observation had been casual; but when they made ready to leave the park the suspicion on the man’s face had become so obvious that it brought Martin up with a start. From surprise, he changed to anger; and when they passed the patrolman he stared with such fury at the officer that Alice questioned him. Martin did not answer her, but talked on rapidly about the tennis ball. Then he began to reconsider the situation. It was true that the policeman had been justified. This was New York—a thick, practical city with an imperative demand for the protection of its children. Martin’s anger abated; and when he and Alice reached the drug store he deliberately put an end to his thoughts and premonitions and bought her a fine, new ball. The matter-of-fact way she took it pleased him more than any thanks she could have given him; for it meant he was accepted as a friend.

The little girl insisted that he return to the park next day, explaining that he should use her present first. And when she went dancing away, Martin smiled so broadly that the intense, deft lines of his face were strangely softened. This mood remained until he reached the Bowery, but in his room was completely lost in its solitude. Apprehension for his friendship for this child turned the channels of his mind toward new rivulets, each more forbidding than its predecessor, until he realized there was no oasis of sweetness in the barrens of his choosing. His temporary home, his very style and itinerant manner of living were contributory fences to the land beyond the streets—a land he felt he had invaded. He decided to tell little Alice that he was going across the ocean again, where there were bees that neither stung nor gathered honey, where lady tigers—and then, more tired than he knew, Martin slept.

He saw Alice first the next day and called out cheerily. But the little girl was quiet. She was holding the new tennis ball in both hands and her eyes were lowered.

“What’s the matter?” asked Martin, surprised.

She looked up hesitatingly and Martin was shocked by the expression on her face. He found it difficult to analyze, but there was hurt, and fear, and he thought even horror there.

“My mother told me to never play with you again,” said Alice, and her voice was so thin and far away it sounded like a tiny pipe. “Mother said to give this to you,” and she held out the new tennis ball.

Martin put his hand around it. He was not looking at Alice anymore, nor apparently thinking of her; for his vision was directed beyond—at a disassociated blot of ugliness upon the sky; and he spoke so softly that the girl could but faintly hear.

“A voice like a reed in an Indian wind,” he said. “Like a tender, Indian reed.” Then, without addressing the child, he passed her and walked, with eyes implacably bemused, toward the corner of sky that held the dark and obscene smudge.... That afternoon, upon a street he’d never seen before, he remembered curiously it had been the first time he had cried in a great while.

In the PINE LEAF, next morning, his eyes were clear, his skin bright in the sun; but with all of it, he counted every measure of his heart. This was a dead passage—a ship without wings—men beside him shaving without faces. There was no hastiness in his action, though; and with impassible restraint he left the Bowery, its fretful entrances and lanterns thick with sickness.

He went uptown to the Relief Employment Station and stood in line again. Behind and before him, such pitiful neatness would formerly have brought the thought of laughter or poor tears. No more.

A counselor interviewed them quickly. There was a card on his desk marked MR. ROBERTS. Martin studied him with concentration, knowing that this man through whom he might be placed demanded understanding, subtle coyness and perhaps, beauty; for he saw a person hesitant in sex and yet requiring it; a man lurid of cheek, yet pale; a contradiction with a flush abnormal as its pallor. The look of Roberts was more theory than fact; although Martin thought, amusedly, that certainly this personage, most elegant, existed almost regally. The counselor’s eyebrows, alert and thin and dark, commanded all his face. His deep-set cheeks and bold, firm chin absolved too bright, too wide a pouting lower lip. His hair, compressed and black, cut strongly in his temples and took away the color from his eyes. “This masterpiece,” thought Martin, “should be done in platinum; with alabaster, ebony and careful points of gold.” And then, he found that he was next.

Roberts glanced at him.

“Sit down,” he said. “Are you waiting for a ship?” His eyes opened wide, closed intimately, then opened wide again.

“No,” said Martin. “I want a job ashore.”

“Have you had college experience?”

“Yes. Five years.”

Roberts grew cautious.

“Really! Post-graduate work?”

“No. I was never graduated. It was off and on.”

“Why?”

Martin hesitated a moment.

“I suppose because the electives interested me much more than the requisites.”

Roberts spoke impersonally.

“A diploma is quite valuable in getting a job,” he said.

Martin smiled.

“That’s right.”

The adviser looked at him questioningly.

“I wasn’t trying to be rude,” said Martin, “but the situation appeared somewhat ridiculous.”

“I can well imagine,” answered Roberts, smiling back at him. “I wish everyone out of a job could develop the same sense of humor.”

“It isn’t a sense of humor,” replied Martin. “It’s a form of embarrassment. I used to see little girls act this way in school.”

The counselor nodded.

“An acute analysis,” he said.

“I didn’t mean that,” Martin added quickly.

“Of course not.” Roberts was thoughtful. His eyes had assumed a knowing look. His voice was unprofessional and the color in his cheeks had become more prominent. At last, he picked up a card. “What kind of work do you prefer?” he asked.

“I’ve done a good many things.”

“Have you specialized in anything?”

“No.”

“That’s curious. One would think that a young man with your intelligence would——”

Martin interrupted him.

“I’m not intelligent,” he said. “I’m imaginative. Sometimes it gives the illusion of intelligence.” Then, slightly bewildered by his own statement, Martin reflected on this uncalled-for abstraction until he forgot where he was and sat absently, with an appearance so unusual that Roberts, who was watching him keenly, spoke one word half under his breath; and Martin, taken from his musing by the unexpected character of the exclamation, said sharply, “What was that?”

But the adviser, disregarding the question, shrugged his shoulders—basilisk in state once more.

“Are you really ingenuous,” he asked, “or are you kidding me? One would think that a young man of your—education—then, would have prepared himself to meet inevitable economic problems.”

“No.” Martin shook his head. “I’m not ingenuous, either. I’m conscious. I’m too conscious; it makes me brittle. Nor am I kidding you. I told you the truth. It is curious that I didn’t adjust myself. I tried to think about it occasionally but it didn’t do any good. Other things seemed more important.”

Roberts was listening intently.

“What other things?” he asked.

“Oh—pretending. Sometimes other things; but mostly just pretending.”

“Pretending what?”

“Pretending that I was everything except what I am—that things were different from what they are. I thought that life would move on and somehow carry me with it. I have no way to substantiate this; but all my life I’ve known that the finish was illusive—that it was best for me to float with the current until an eddy whirled me into my right course.”

“Have you struck the eddy?”

Again Martin felt the intimacy of Roberts’ tone and frowned.

“Perhaps you misinterpreted my question,” said the adviser coolly. “I asked if you were in your proper medium.”

Martin flushed and started to rise; but Roberts lifted his hand in a gesture of restraint.

“I really know how you feel,” he said gently. “Perhaps that’s why I spoke as I did. In your capacity as a job hunter, however, there can be no room for individual conflict; particularly in your relationship with one who, understanding, offers both his professional facilities and,” he said more slowly, “his friendship—” all the time looking directly at Martin with the strange color coming and going as he spoke.

“Cheeks—like a lost woman,” said Martin, trying to stop the sentence before it was out of his mouth.

Roberts stared at him for a second in astonishment. Then he went into uncontrollable laughter.

But Martin remained unsmiling.

“I’m sorry I said that,” he remarked severely. “I really can’t excuse it or explain it.”

“Well, I’m not sorry,” said Roberts, leaning forward. “It’s the first genuine fun I’ve had in a long time. I’d like more of it. But I’ll confess—it’s disruptive to the morale of the office.” Still amused, he glanced around him. His speech was high and unbalanced. “However,” he went on, becoming more practical, “I’m going to get you a job.”

“Well—” said Martin.

“No, no,” insisted Roberts. “I’m glad I’m in a position to help you.” Once more, he looked swiftly around him and continued in a lower voice. “I think it’s wonderful to be able to help people. Don’t you?”

“Yes.”

Roberts hesitated.

“It’s about the only thing there is in the world,” he said in a still lower tone. “Isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

He wrote his address on the card and handed it to Martin.

“I want you to come to my residence this evening. There, we’ll work out your economic destiny.” He smiled faintly.

Martin accepted the card, smiling also, wondering if he really looked this subjective and, if not, why Roberts’ obvious attitude.

“Very well,” he said, facing with curiosity a phenomenon before its occurrence. “What hour?”

“Nine.”

Martin stood up and nodded slightly. It seemed to him that the employees were watching him evasively as he left.

The great city arose with Martin and marched to its hysteria of noon. Then, slowly falling till evening, burst into flame, quieted and slept. Gigantic presses told of her neurosis. In this immutable turning flashed black lines of the growth of the disease. Its people, wooden-eyed, marionette, accepted with grimness; their minds numb and evasive. They held their buildings higher in the air—pointed them like caricatures of things that had gone, of things still to come. But their thoughts were buried. Hidden under music and dust and smothered in light, the precious balance died....

The moon, free of clouds, shone through the blinds and into the living-room of Roberts’ apartment. A crystal vase, without flowers, directed the dim light into a corner. Small ebon figures held out their arms. Roberts was wearing a dark Russian blouse. To Martin, he appeared more fabulous and crystalline than in his office. His flush was constant—so determinate that Martin guessed it artificial, noticing however, that the native, restless color had moved into his eyes. There it remained, fluctuating and searching until it seemed disturbingly like the luminant phosphorus of uncertain, yet violent leaves and shadows Martin had avoided in the tropics. Roberts had been ambiguous throughout the evening and Martin felt that he knew him no better. But he watched the adviser closely—watched each apparent banality for a double entendre and speculated upon the inevitable. He countered each triviality; and made no attempt to acquiesce in a secretive understanding.

Roberts now grew silent for long intervals. With a compelling, but a quiet vision, he observed his young friend. The room had become warmer and frost was forming on the window panes. Once, Roberts arose and ran his finger across the glass, leaving a clear, narrow trail from which fell small drops of moisture.

“It’s colder outside,” he said.

“Much colder,” replied Martin.

Roberts came over and sat down near him.

“Then I take it the warmth of our civilization has its appeal after all?”

In a different fashion Martin confused the scene in as remote and complex a pattern as his friend. Deeply muscled by the sea, he nevertheless was finely drawn as a lady’s slipper and as quick of kicking to the notice. Roberts was aware of this and other features that, to him, were more demanding and elemental; for in his bleached eyes Martin carried the ocean; there was the smell of salt about him—and, Roberts thought, in a sort of painful hysteria, probably sand in his hair. His face, out of the Indies, with its stain from the sun and from his youth, should not hold dignity; and yet it did, in such a steady, high intensity that Roberts caught his breath on it. Martin rubbed his foot over the rug.

“‘Warmth’—of your civilization?” he repeated. “I’m astonished.”

“Perhaps the word was ill-chosen,” answered Roberts. “But whatever our qualities may be, I hope that you prefer them to those which emanate from the fo’c’sle of a West Indian freighter. Now, it is my turn to be astonished. Why did you say ‘your civilization’? Are you not—” Roberts hesitated, “one of us?”

“I’m a seaman. We don’t fit in anywhere on land.” Roberts changed—seemed more severe in the passing light.

“This bold and masterful deception of all seamen is, to me, Martin, a shabby thing. I see it as a trite avoidance of each standard which, although sometimes unbeautiful, is present in the world. Such life, irrelevant and irreverent of all doctrine, is but a switching of responsibilities—a turning of the back that’s shielded by mere boastfulness. In honesty to myself, I must admit that there’s a careless beauty in its physical, sweet shape—the wrap of dungarees—and forgetfulness in song. And yet, it’s impotent. Quite sterile in its loveliness.... And finally, I see the man—the dungarees—the very songs in pity.” The color surged into Roberts’ cheeks and he leaned nearer. “You’ve abused yourself, Martin. There’s been dishonesty in plenty for yourself. And what, dear boy, quite comes of it?”

“Perhaps I do it to hear you drain yourself,” said Martin dryly.

Roberts answered with immediate fierceness.

“I don’t believe I’ve ever talked this way before. But I’ll use your method now, Martin. You need a job. From your card I noticed that you’ve been a printer. Can you operate a linotype?”

“Yes.”

“Then I’ll arrange things. Now, in heaven’s name—let’s leave this miserable economic status. It’s impossible.”

Martin frowned slightly.

“But isn’t that why I’m here? You said—”

Roberts’ blue eyes became darker.

“Why not quote our professional introduction literally?” he asked. “You were trying to amuse yourself, not help yourself. Why did you do it? Why do you do it now?” With difficulty he restrained his anger. “A job should be considered first, before this premature folly.” He stopped, put out his cigarette and waited, only to be startled by Martin’s sudden laughter. He raised his shoulders arrogantly. “You are entertained then, by emotion?”

“No,” said Martin. “Rather, by a grotesque episode.”

“Grotesque?” Roberts seemed more contemptuous than indignant.

“Indeed,” said Martin, inflamed by this dry attitude. “Grotesque. Absurd. A farcical horse-opera of a lost decade revived in different ribbons, different sex. This renovated melodrama is enough to make one sick!—a pale girl with a stack of mortgage documents fastened in her long, blonde hair, arguing for her virtue with a Russian blouse!”

Roberts listened with fascination. His eyes became solicitous. The tenor of the room altered swiftly.

“You could have been, Martin,” he said in a breath and quite excitedly. “Yes, you could have been.” And then, between his lips, and with no intended insult, Roberts spoke the same one word that he had whispered to Martin that afternoon.

Martin looked at the man and knew this exclamation had never been so used. Without changing his expression he reconstructed Roberts’ face from the fragments of thought that had suddenly charged the room. The pink, hairless mask moved closer—without eyes, without nose, with a single hole in the lower part and a single, dreadful sound protruding.

Along the blinds lay a few ravelings of light. The face regained its natural shape. Only an undermovement of greediness and a distant, crying sound remained.

Roberts walked over to a cabinet and brought back a colored liqueur which he offered to Martin, pouring it slowly and meticulously into Holland glass. He was once more the host, aloof, charming, courteous.

“How do you think you will like your job?” he asked. “I’m sending you to a friend of mine—a Mr. Jackson. He’ll see that you get along.”

“There’s no reason to lie,” Martin answered. “I won’t like it. It’ll be wretched—sitting there, pounding a machine that is more efficient than I am.”

“Then tell me—why do you want a job ashore? Why don’t you go back to sailoring? Or, do you really like that sort of thing after all?”

“It’s a free life,” Martin answered slowly.

“And this is not?”

“I don’t know. But your evaluations interest me.”

Roberts became genuinely curious. All of the coldness left his face and only the deeper lines of his integrity remained.

“What is it that disturbs you, Martin?” he asked gently. “The past or the future? Or the shadow behind the lamp?”

“I imagine the shadows are worst.”

“You intensify them, don’t you?”

“Perhaps I even create some of them. We demand contrast.”

“Mmm.” Roberts, his head nodding loosely, studied him. “You have something in your eyes, Martin,” he said. “If you were a woman I would forget my business, my complacency. I would want to run away with you—if you were a woman.”

Martin hesitated a moment before answering.

“If I were a woman—you would not be interested,” he said at last.

Roberts’ face grew white under the rouge.

“You are candid. But my temperament should not disturb our friendship.”

Martin leaned over, closing his hand about the adviser’s wrist and holding it tightly.

“What do you mean by ‘temperament’?” he asked.

The insolent red came back into Roberts’ cheeks.

“That was young, Martin, my lad. It was cruel.” Then, sensing the flux of blood upon his wrist more keenly, he felt curiously strong. Happiness, nostalgia and strength merged and fused until his mind turned slowly and hung staring down upon the stages of his life. Two pale stars drifted upward and dimmed. Roberts looked into his mother’s eyes.