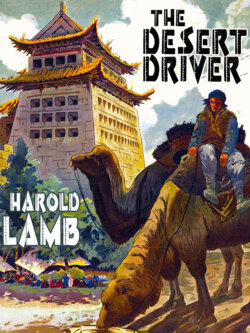

Читать книгу The Desert Driver - Harold Lamb - Страница 5

CHAPTER I

ОглавлениеAn Accident

NO TRAFFIC cop has a post in Donkey Meat Street. A jumble of rambling motor cars, bullock carts, carriages and jinrickshas use their own judgment and the result is chaos. Donkey Meat Street is in Pekin.

If there had been a traffic cop at the crossing, Tim McMahon would not have had to jump for his life out of the way of a big red sedan that swung around a mule cart. As luck had it, he jumped backward—a good, healthy leap that propelled him against the chest of the man behind him.

Tim McMahon is stocky, big-boned, and sturdy in the leg. The man behind was knocked into the gutter. McMahon turned around with a muttered apology ready on his lips, and saw a round-faced Chinese youth in a suit of Americana tailoring. It was a costly suit, and just now, smeared with mud from the gutter.

There are a lot of things Chinese do not like to have done to them, and one is to be shouldered out of the way. The young man who climbed out of the gutter could speak English and did speak pointed, vitriolic English.

Now Tim McMahon had missed three meals in the last twenty-four hours; his clothing was shabby, and a sandy growth of hair covered his bare head, chin and upper lip. He was out of a job and broke and his temper was none of the best. His left hand snapped out at the insult.

The head of the tailored man flew back on his shoulders, and when McMahon’s right followed to his jaw he rocked on his heels a second time and sat down on the curb. He put his hand to his lips, and saw that his fingers were bloodied. Slowly his face turned red, and he rose on one knee, his right hand feeling his thigh tentatively. The next second a blue, Colt six-shooter was in his hand, and a shot bellowed through the shouts and peddlers’ cries and creaking of wheels on Donkey Meat Street.

The bullet, instead of striking the surprised McMahon, soared harmlessly up into the air. A man had stepped from the watching throng, had caught the young Oriental’s wrist and jerked up the weapon The Chinese looked up into a pair of gray eyes belonging to an American foreign devil.

A moment of twisting and straining, and the revolver was in the newcomer’s possession. At once, and as if familiar with such operations, the man of the gray eyes snapped open the Colt, shook the six cartridges into his left hand, transferred them thence into a pocket of his jacket, and handed the Chinese youth back his weapon.

Then the American nodded significantly to where a gray uniformed soldier was peering from a sentry box across the street, and the Chinese gunman faded back into the press of his countrymen. The stranger turned to Tim McMahon.

“Come away,” he said.

The two white men walked around the mule cart, stepped out of the way of a laden coolie, crossed under the horns of a pair of bullocks and passed from the sight of the sentry, who returned thankfully to his box. The crowd moved on, pursued by a smattering of peddlers, and Donkey Meat Street came back to normalcy.

In this way began the very strange history of the teakwood box; a history that had its prelude in the alleys and hotels of Pekin in the year I923 the Christian era, and its end in the vast spaces of the Gobi desert. That is, if a tale that goes back to the first ages of Time itself can have a beginning.

“You act,” said Tim McMahon, “like I done wrong. How d’ye get that way?”

“No,” responded the stranger, “I merely said that when you strike a Chinese, you have to watch out for trouble, and keep on watching out for months or years. That young snake in the mail order clothes was probably the son of a wealthy merchant or official of the mandarin class. Have you any friends in Pekin, McMahon?”

Tim, of the sandy hair and deep-set blue eyes, sat down on the stranger’s cot, asked for and got a cigarette, threw off his coat and opened the collar of his flannel shirt. It was hot in the room of the small hotel.

No, he said, he had no friends west of Jersey City. He was a mechanic by trade, had once had a berth as driver of a motor repair lorry in France. He had stoked his way across the Pacific, had looked for work along the railroads in the coast district of China, and had grabbed a rattler to Pekin. So he had come to learn that of the few jobs open to white men in China, the good ones were filled by men sent from the United States or Europe, and the poor ones by half a dozen Chinese to every job.

“What’s your line?” he asked.

The stranger smiled wryly. He was a slender man, quietly dressed in a way that made McMahon think vaguely of an artist or a foreign chap. Perhaps because of the close-clipped reddish beard and the high, bald forehead over the alert gray eyes.

“Selling typewriters,” he answered. “I’m Robert Warner. Came across from the States a year ago.”

Over his cigarette McMahon considered the acquaintance who had “got him out of a jam.” But for the quick action of the stranger, his wanderings might have ended at Donkey Meat Street.

He reminded McMahon of men who had been to college, or army officers. There were black boxes under the cot that looked like filing cases, and several queer Oriental paintings on the wall, with an ancient Chinese repeating cross-bow.

“Any luck, Mr. Warner?”

“Rotten. ’Most every merchant in Pekin has a typewriter.” Warner grinned, his short beard bristling. “Yesterday I called on a big name of Fu Cheng, curio dealer. Talked to him half an hour in my best Pekinese; then found out he spoke English as well as I—had come over a few months ago from a ten years’ stay in San Francisco, and had three of the portable typewriters I’m selling. Fancy his listening to me for half an hour, and reading through all my credentials!”

Now the cigarettes were of a good, American brand; the ash tray was real ivory. Tim wondered how Warner had lived for a year. “This line,” he said, “about the heathen Chinee is bunk. It’s all wrong. These Chinks are wise; they’ve changed their skin. Look at out there.”

He indicated the electric lights and trolleys of the Pekin streets, and the big radio tower that loomed over the old city wall. “I ask you, Mr. Warner, ain’t that so? I ask you, does the young cabaret hound I knocked down on—”

“Donkey Meat Street.”

“Does that cabaret hound slink around after me and give me a shot of feng shee or—”

“Feng sha? Magic?”

“You get me, Mr. Warner—yellow magic, or poison or any of that line of stuff? No, he goes for his gat. These Chinks is up to date. They don’t have no tong wars, or ancestor worship, or opium—maybe they do sell that to the dope dealers in the States. No, these fellows are out for the jack and Chicago-made clothes.”

For the past minute Warner had been extracting a folded Pekin newspaper from a pile on the table. It was printed in English, and he handed it to McMahon, pointing out a marked paragraph. “Read that.”

MOTOR ACCIDENT

On Donkey Meat Street near the British mission yesterday a large gray limousine ran into and seriously injured a smaller car belonging, it is alleged, to the Cheng Curio Company. The driver of the damaged car was thrown out and escaped death only by a fortunate chance. The police of Pekin are trying to trace the ownership of the sedan which sped away after the accident, with its cut-out open.

“I said it,” grunted McMahon. “Why that jam might have happened at Forty-Second and Fift’ Avenoo—only there wasn’t no traffic cop.”

Warner’s quiet eyes blinked. “No, there are no traffic cops. No one interferes. And accidents don’t happen, in this part of the world. They are made to happen.”

“You can’t tell me!” McMahon thought of his recent escape. But his companion, who had been observing Tiim closely, noticed how husky his voice was and how weakly his hand moved. He judged that McMahon had not had a square meal for some time.

“Look here,” he said. “You can help me out. Are you handy with machinery?”

“You said it, Mr. Warner.”

“I know you can scrap, and keep your mouth shut. But can you—or rather, will you—obey an order, McMahon?”

The mechanic thought this over seriously. The qualifications Warner had enumerated were not those of a typewriter salesman’s assistant. “If I’m minded to, Ican that, Mr. Warner.”

“Well, consider yourself hired—if you’re willing to bunk in with me and willing to run the chance of the ghost never walking—no pay day. And, my name’s Bob, to my friends. And the first thing on our program is tiffin.”

“What’s that?”

“Eats.”

But before the two white men could wash and go down for a late luncheon there was a knock on the door, and McMahon sat down on the cot again with a sigh as a black-suited Chinese appeared in the entrance with a succession of bows. “Mlister War-ner?” he asked, smiling.

“Yes,” said Warner, and took the note the man—who might have been either servant or clerk—held out. He read it through carefully and nodded. “Very well.”

“All light—you come plitty soon?” The messenger bowed himself out, and Warner sprang up, whistling cheerfully as he plied comb and brush on his sparse hair, considering the result critically in the cracked mirror.

“Looks as if we’re going to make a sale, McMahon. Letter from Cheng, the merchant I called on, asking me to come around again this afternoon on a matter of business. On the strength of that we’ll have chicken.”

McMahon extinguished his cigarette promptly. “Nothing could be fairer than that. Say, Mr. Bob, my name’s Mac, to my business partners. D’ye get me?”

“All light, Mac.”