Читать книгу Not Without You - Harriet Evans - Страница 11

CHAPTER SIX

ОглавлениеUP IN MY white bedroom, I take off my clothes and stand naked in front of the mirror. I turn around slowly, appraising myself. I hate this part so much but it’s my job, this delicate balancing act. You can’t have any fat on you, yet you don’t want to end up like Nicole Richie. It’s not a good look for a bona fide A-Lister being scary-thin – unless you’re Angelina, but Angelina’s a basket case. I turn slowly. My butt is still high, and firm. When I turned thirty a couple of months ago, Tommy suggested I get it lifted before it needs to be, but I told him to fuck off in such definite terms I don’t think he’ll mention it again. My tits are good – I wish they were bigger, but bigger means you’re fatter and so far I’ve had no complaints. Tommy’s suggested having a tiny lift in a year or so. He says it just makes the job easier later on. I cup them in my hands, thinking about tonight, wondering what George will make me do, what I’ll do to him. I shiver with anticipation and smile at myself in the long mirror, shaking my head at my stupidity; but it’s so good to have someone to go and be this person with, someone who understands, and he does.

And then a shadow on the bed reflected in the mirror catches my eye.

At first I think it’s just a crease in the sheet, but when I turn around and walk towards the bed, I realise it’s not. It’s a rose. A perfect, white, single rose. There’s the faintest hint of cream in the soft buttery petals, and when I pick it up I cry out, sharply, because it has thorns. It smells delicious.

I suck my thumb and look towards the window, almost expecting to see a face there, but this side of the house looks directly over the hills and the road and they’d have to be suspended 30 feet above the road to get a good look in. I pull on some sweatpants and a top, hurriedly peering into the bathroom, then into my closet, but there’s no one. A hair on my neck itches, as if there’s something else there.

So I tell myself I’m overreacting. It was probably delivered to me and left here by Tina. Or maybe Deena stole it from somewhere and left it as a present. There’ve been guys in and out of the house all day, fixing the TV, steaming the carpets. Probably some loser trying to make a joke.

Why do white roses ring a bell though? There’s something about them that makes a knot tighten in my stomach. I can’t put my finger on why. I stand there for a moment trying to remember, then suddenly I pick up the rose and throw it out of the window. It loops awkwardly in the air and disappears. It will land on the road below me and be crushed by a car and it’s nothing – I’m being stupid. I go downstairs, to try and find something to eat.

Carmen is clearing up, polishing the wood. ‘Carmen,’ I say. ‘Did someone leave a rose for me on my bed?’

She frowns. ‘What?’

‘A rose. Single stem.’ I sound insane; I wish I hadn’t thrown it away.

Carmen gives me a curious look. She shrugs. ‘No, Sophie, I have not seen a rose. No roses here.’

‘Where’s Tina?’

A slight spasm crosses Carmen’s face. ‘She on the phone outside.’

Tina is standing by the pool whispering urgently into her cellphone. I clear my throat and she jumps, automatically putting her spare hand on her head, like she’s been busted in a police raid.

‘Oh! Sophie. Hi there!’ She kind of bellows this at me. ‘Are you OK? Do you need something?’

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt.’ I feel stupid, even asking. ‘Er – did you put a rose in my room?’ I say.

She looks understandably confused at this question, though her rigid forehead remains immobile. ‘Uh – no, I didn’t, Sophie—’

She must think I’m going mad today. ‘Not you personally,’ I say impatiently. ‘I mean did someone ask you to or did they drop it off there? I was just in there. There was a white rose on my bed.’

‘I don’t know,’ says Tina. She narrows her eyes and then clears her throat. ‘Do you think someone was in the house?’

When she says it like that, it sounds kind of sinister, and I don’t want to hear it. ‘I’m sure not,’ I say. ‘I bet there’s a perfectly simple explanation.’

‘Sure,’ Tina says. ‘Let me just call Denis.’ She dials the gatehouse. ‘Denis, can you read me the list of who’s been checked in today? Uh-uh … sure. Sure.’

She ends her call. ‘You, well, you and T.J., the carpet guys, Juan was here in the garden, me, Carmen. The Mulberry guy but he didn’t come inside. A FedEx guy, ditto. We can go back to the carpet company too, see who came in, ask them if they left it. OK?’ She sounds calm. ‘I’m sure it’s nothing.’

‘Thanks.’ I believe her. It could be any one of several things. There’s something about Tina – she is totally capable and calm dealing with my shit. I know I can totally trust her. Yet anything to do with herself is a different matter. I chew the inside of my cheek. ‘Look – Tina, I’m sorry about before,’ I say, edging towards her. She looks suspicious. ‘About you taking time off. It’s just two months is a long time, and I wanted to make sure – you are OK, aren’t you?’

She shoves her phone in her pocket and scratches her face. ‘Of course I’m OK. I just don’t want to talk about it much.’

‘Right,’ I say, and then fall silent.

‘You are right. It is a surgical procedure,’ she says eventually. ‘It’s my lips. Yeah.’ She’s looking at the pool and I’m looking up at the sky, both pretending this is a normal conversation. ‘I was stupid. I got fillers from some quack doctor years ago. He screwed them up and I haven’t been able to get them fixed.’

‘Why?’ I say. ‘Couldn’t you sue him?’

She smiles. ‘That costs money. I don’t have money. I wasn’t properly insured when I did it and it’s kind of impossible to fix unless you totally know what you’re doing. I’ve finally found someone on my insurance who’ll try and take some of the fillers out but it takes a few weeks to remove them. The surgeon’s in Vegas, so I’m going to stay with Mom …’

‘You should have asked me,’ I say. ‘I’d have helped you.’

‘Helped me take them out yourself?’ she says, with a glimpse of mordant humour. ‘Right. No, I need to …’ Tina looks across at the pool again, out to the city sprawled below us. ‘Some guy at a seminar told me if I got them done then I’d get more jobs, and I listened to him. Biggest mistake of my life.’ Her eyes fill with tears.

My heart aches for her. ‘So … you were an actress?’

She takes a tissue out of a pack and delicately wipes her nose. ‘A model.’ She adds, with a rush of bravado, ‘In fact I was Miss Nevada 1998.’

‘No way!’

‘Uh-huh.’ She’s smiling. ‘They said I’d be a star, but I didn’t want that. All I ever wanted to do was be a Victoria’s Secret Angel. I loved those girls.’

‘Wow.’ I am amazed at how people give themselves up to you all in one go. ‘I never knew that, Tina. You’re beautiful. You should have—’

‘It’s a long time ago. And it didn’t work out, did it.’ Her shoulders slope again and she adds, with something more like her normal tone, ‘I came to LA, so sure I was going to be a star, you know?’ I nod. ‘But nothing was really happening, and a year later I had this done. It ruined everything, I was broke and ugly. No one wanted me. That’s when I started working for Byron.’

‘Is that what you really wanted? To be famous?’ I am fascinated at the idea of this new Tina, the gorgeous young beauty queen and the awkward, withdrawn woman she is now.

She hesitates. ‘It was all I ever wanted. Then. Of course, now it’s different.’

‘What do you want now?’

‘Now – you know what I want now?’ I shake my head. I literally have no idea. ‘I want a nice house, near the ocean. A good guy, a couple of kids, a normal life. And I want to stay working for you so I don’t leave that world behind, because I love it. That’s really all.’ My expression must be incredulous, as she laughs and says, ‘I like working for you, Sophie. You’re doing so well but you’re easy to get along with – you’re talented, and you’re not crazy. You need someone to look out for you. And forgive me, but you’re kind of naive about some stuff in this town.’

This is completely fascinating. ‘What stuff?’

But before she can answer, a husky voice calls from around a corner.

‘Hey, doll.’

We both jump as a thin shadow falls on the ground, advancing towards us.

‘All right, Tina. Hi. Sophie. Wow. The gang’s all here, yeah?’

I blink, sunspots dancing in front of my eyes.

‘Hi, Deena.’ I kiss her, inhaling the familiar scent of cigarettes, sweat and Giorgio Beverly Hills. ‘You got everything you need over there?’

‘Yeah. Nice painting in the bedroom. Is it new?’

‘Yes,’ I say shortly.

‘Cool. Cool. I like its vibe. It’s all good. Listen, kiddo. Just wanted to say thanks, OK? Thanks for having me. Damn air con. It broke and then the water tank went and the whole house was flooded.’

‘I thought it was—’ I begin, then stop. What happened to the roaches? Tina glances at me, and looks at the floor. ‘Hey. No problem. Stay as long as you want.’

Damn. As soon as the words are said I wish I could reach out and cram them back in my mouth. ‘Hey, nice one, kiddo,’ says Deena. ‘We gotta look out for each other, haven’t we?’ She tips the imaginary brim of a hat to me. ‘Listen, there’s no kettle in the guest house.’

‘Kettle?’ Tina frowns.

‘You guys don’t do kettles. It’s fine. Just wondering if you could put one in there for me.’

Bloody cheek. I sigh and look at Tina. ‘Er …’

‘I’ll talk to Carmen on my way out.’ Tina nods at me. ‘So – I’m off now. I’ll see you tomorrow. You have everything you need?’

I nod, trying to meet her gaze, but she’s already halfway down the drive. ‘See you tomorrow. Thanks again.’

‘Odd gal,’ Deena says, after Tina’s vanished. ‘So how’s tricks? You’re on fire, en fuego, at the moment, huh? Everything lining up for little Sophie Sykes!’ She gives me a big wink. ‘Hey, sorry! Sophie Leigh.’

She says this like she’s revealing a massive secret about me, like I was born and raised as a boy, when in fact you can see my name’s Sophie Sykes if you go on IMDb. It’s not even an interesting story: Mum made me change it when I was sixteen because she said Sykes was too common, much to my poor dad’s resigned amusement.

I’m trying to think of the right answer to this when Carmen appears at the French doors. ‘Sophie. I got your dinner here. You want it outside?’ She looks at Deena. ‘Ma’am, can I get you anything?’

Deena runs a finger thoughtfully over her teeth. ‘Hm. I don’t know. What you got?’

‘Anything,’ says Carmen. ‘What you want?’

‘You got some ham?’

Carmen folds her arms. Her brows lower into one bristling black line. ‘Sure. I got some ham.’

‘Can I get a ham sandwich? With … some chips on the side. And some guacamole. Can I get that?’

Carmen says briskly, ‘Sure. No problem.’

She’s just retreating inside when Deena adds hopefully, ‘And a beer?’

‘You want Peroni, Budvar, Tiger? We got—’

‘That’s fine, just bring her anything,’ I say. ‘And thank you, Carmen. Listen to me, Deena.’ I move inside through the French doors, motioning her to follow me. ‘It’s fine for you to stay. But I might be having someone from the UK over in a couple of weeks, so …’ I scratch my head, searching for a name, any name. ‘My friend … Donna? My friend Donna’s coming to stay, yeah, probably in July? Just so you know.’

Deena takes a Zippo lighter out from a pocket in her impossibly tight jeans and starts flicking it on and off. ‘Listen, kiddo, I don’t wanna outstay my welcome. I said two weeks, I meant two weeks. I’m busy, you know. I’ve got a lot of stuff on. It’s just while they’re …’ She falters, and I feel like a total bitch. ‘While they’re fixing the drains.’

‘Of course.’

She moves a little closer. She’s always looked the same, Marlboro Man’s girlfriend: jeans, silk shirts, tasselled suede jackets. I see the flecks of brown in her hazel irises, the shadows under her eyes as her gaze meets mine, but then she swallows and says, ‘Yeah, like I say, I’m busy. Got a TV pilot I’m auditioning for next week, did your ma tell you?’

‘I haven’t spoken to her in a while.’

‘Hm, I know, she said.’ Deena’s still flicking the lighter. ‘She calls me when she can’t get through to you, you know that? You should call her.’

I change the subject back. ‘That’s cool, what’s the pilot?’

‘Oh, it’s about this chick who lives down in New Mexico and … has a lot of fun.’ She smiles enigmatically. ‘And I’m working with a European director on a couple of projects. Made an advert for German TV a few months ago. It’s all good.’

I would love to follow Deena one day. Just see what she gets up to, how she makes a living. Whether she’s totally feral when no one’s watching, living out on the hills and heading into the city to feed off scraps from restaurant bins. Her last entry on IMDb is 2004, some straight-to-DVD thriller. But she always tells Mum she’s shooting a new pilot, or working with a European director. I am sure ‘European director’ is code for something.

Carmen brings in my tray of food. I make a vague gesture to Deena but she shakes her head. ‘No, thanks. I’m gonna grab my sandwich and go. Got to see a guy about a fido, you know?’ She slings her battered old leather satchel over her shoulder. ‘See you later, kiddo. Thanks again.’

‘No problem.’

She’s halfway out the door when she hesitates, turns round and adds, ‘Hey. We should talk while I’m here. I’ve got a few ideas I wanted to run past you. Really good ideas. Maybe you could get me a meeting with … with some people.’

Everyone wants something off you, that’s the deal. I realised it when a camera boom hit me in the face while I was filming Sweet Caroline and the triage nurse at Cedars-Sinai gave me her head shot while blood was pouring from my scalp. It’s money. All to do with money, whether they’re aware of it or not. So I nod and I say, ‘Sure. We’ll talk soon. Bye, Deena,’ and wave politely, as she strolls out of the room.

Carmen is setting up the tray as I settle back into the La-Z-Boy recliner. There are fresh copies of Us Weekly and People on the coffee table – I reach for the former, then put it back with a sigh, knowing it’s for the best: it annoys me when I’m not in it, and it annoys me when I am. There was a time when I used to Google myself. I even had my own sign-in on a forum devoted to ‘Sophie Leigh Rocks!’ But I had to stop. Even the ones who like you still say things like:

I think Sophie’s hair needs extensions or filling out, it’s really thin/rank lol

Why isn’t she on Twitter? Why does she think she’s better than us? Won’t she give back to her fans who <3 her n made her what she is?

I fucking hate her. Liked the 1st film and now it’s like oh my fucking god how many times can one person play a dumb bitch. That cutesy act makes me want to barf.

And this particular highlight from a ‘fan site’:

Who does she think she is? She acts all smiley and perky and she’s NOTHING. Mate of mine knew mate of hers on South Street and said she was a fat slag who reckoned herself, had no talent and f*cked her way to Hollywood. Apparently she gave head to anyone who’d ask. Also her breath stank because of how much head she was giving. Gross.

Nice, isn’t it!

I switch on the TV. TMZ is on. They’re standing around talking about Patrick Drew. He was filmed coming out of a club in West Hollywood, his arm around some girl. She’s supporting him. He sticks his finger up at the paps, and then he’s pushed into a car by some entourage member. He is beautiful, it’s true.

‘Car crash,’ says Harvey, the TMZ head guy, who’s always behind the desk leading the stories. ‘That’s a night out with Patrick Drew.’

‘What about Sophie Leigh?’ one of the acolytes says. ‘He’s filming with her next. Maybe that’ll do him good.’

‘Sophie Leigh?’ Harvey says. ‘She’s too stupid even for Patrick Drew.’ They laugh. ‘How snoozefest is that movie gonna be? Him crashing into walls on his skateboard, her smiling from under her bangs in some titty top, following him round, saying, “I LOST MY RING!”’ They all join in and collapse with laughter. ‘“Oh, here it is, Patrick!”’ Harvey mimes a ring down an imaginary cleavage. ‘“Oh, it’s here, here are my tits, look at my tits!” Then an argument with a mom or a wedding planner, yadda yadda yadda. GET ANOTHER HAIRCUT, LADY! BOR-ING.’

‘I liked one of her movies,’ says a girl behind another desk, taking a sip of her coffee. ‘The one in LA. What was it called?’

‘You’re a moron,’ says Harvey cheerfully. ‘Seriously, these people. Patrick Drew doesn’t give a damn so at least you give him props for that. But Sophie Leigh – oh, man, I hate that girl! She’s so fucking fake and smiley and you know she’s going through the motions for the cash. “Hey, honey. Put this tight top on so the guys can stare at your tits. Now smile, now say this pile of shit dialogue and put on a wedding dress the girls like, repeat every year till your tits reach your knees and everyone’s died of total boredom …”’ He looks up. ‘She’s probably watching this now. Hey, Sophie! Your films suck! Message from me to you: I LOST MY WILL TO LIVE!!’

His voice is deadpan. The others are laughing hysterically. I switch the TV off and lean back in the chair, pretending to smile though no one’s watching. My heart’s beating. My BlackBerry buzzes.

Sorry babe, have to rain check tonight. Keep your tight ass on standby. I’ll need u soon. Hard for u when I think about u. G

Oh. Well. It’s very quiet in here. In my head I list the things I love about my life. I think about the house, my white bedroom with the closet filled with lovely clothes, Carmen’s ceviche, my firm smooth body that the best director in town says he wants, the cache of Mulberry bags I haven’t even looked at yet. I have to count like this; otherwise I’d go mad, and sometimes I wonder if I’m not going a bit mad, and it’s just that everyone else here is too so I haven’t noticed. I wish I had someone to talk to about it, someone I could ring up now and say, ‘Hey, could you come over?’ But there’s no one. Somehow. And that’s my fault.

I shiver, and switch over to TNT. Lanterns Over Mandalay is on. Eve Noel is a nun in the Second World War and she falls in love with an army captain, played by Conrad Joyce, while they’re fleeing the Japanese occupation of the city. Something tragic happened to Conrad Joyce, too, I forget now. He was killed? He died young anyway, then he totally fell off the radar. Hardly anyone remembers him now, but he was just divine. I gaze admiringly at his firm jaw, his sleek form in uniform which is immaculate despite the fact that they’ve just crawled through several miles of mud and barbed wire.

‘Damn it, do you know what you’re getting yourself into?’ Captain Hawkins demands angrily. ‘Diana, you’re a fool if you try to take these people out of here. We can manage it alone, but to attempt the rest – it’s suicide!’

I pull the rug over me, snuggling down so I’m as comfy as I can be and as hidden away as I can make myself. The black-and-white figures on the screen seem to glow in the darkening room. A world I can lose myself in where everything is, like the line says, fine and noble. I stare hard at the screen, sharp tears pricking my eyes.

‘I know, Captain. But I won’t leave them here to die. I simply won’t.’ I’m mouthing along with her, watching her perfect rosebud mouth, the dark, intelligent eyes that hint at something but never quite tell you what their owner is thinking. ‘I’m standing up for something I believe in. I’m trying to do something fine and noble in this awful mess. I’m trying to do something wonderful.’

Where is she? I look around our house, wondering how she came to lose her life here. How maybe I have mislaid mine.

I’ll be around

Hollywood, 1958

EVERYONE WENT TO Romanoff’s. It had started life as a small bistro on the Sunset Strip, run by His Imperial Highness Prince Michael Alexandrovich Dimitri Obolensky ‘Mike’ Romanoff (otherwise known as Harry Gerguson, a small-time crook from Brooklyn). I never did find out where he acquired his knowledge of Russian aristocracy or English country houses – he was able to describe the guest bedrooms at Blenheim Palace in detail to me. Perhaps the library at Sing Sing was particularly well stocked. But despite the fact that he was a crook, and the food was middling to fair at best, everyone went there. When I say everyone, of course I mean stars. By the time I was first taken there, it was well established in Rodeo Drive. Almost two years had elapsed since I came to Hollywood but it was still the place to go and be seen.

One fresh evening in March, Gilbert and I drove there for supper. We were both feeling extremely happy, on top of the world, in fact. We had just that day completed the purchase of a house just off Mulholland Drive called Casa Benita: a sprawling white clapboard bungalow high in the Hollywood Hills, complete with tennis court, swimming pool and suitably impressive views. We had looked at places in Beverly Hills, but I wanted to be able to see the city, not be right in the thick of it.

You were part of the club if Mike waved you into Romanoff’s without a reservation. I had seen him turn away millionaire oil barons, nouveau riche Valley residents, and New York society matrons by the dozen. Aspiring producers, new punk actors, hotshot directors – all were shown the door. Yet Gilbert and Mike were old pals, and at some point Gilbert had obviously helped His Imperial Highness out. Whenever we turned up, there was no problem.

‘Get a table for Mr Travers and Miss Noel. Snap to it, boys. Miss Noel, may I take your coat— Who, those sons of bitches? Fat fucks from Wyoming – get rid of them.’

Gilbert was always in a good mood at Mike’s. His old cronies were there, the rest of the original Rat Pack that had hung around Bogie when he was alive. A lot of people had deserted Gilbert when he came back to Hollywood after the war. It was the way of these things: they called him a hero, but the truth was he’d been out of pictures for five years, was heavier and older and things had changed. The audience had moved on, and Gilbert Travers’s brand of charming English gent wasn’t what American teenagers were looking for. I winced whenever we passed a billboard for Jailhouse Rock. Gilbert hated Elvis, with a passion that was almost violent.

As we sat down at a discreet banquette, an executive from the studio with whom I’d dealt on my last film, The Boy Next Door, passed behind us. ‘Great work on the Life magazine spread, Eve,’ he said. ‘Mr Baxter’s delighted they chose to run the feature about you.’

‘Two White Ladies.’ Gilbert flicked his hand to the waiter. ‘They’re lucky to have her,’ he told the executive. Then he gestured to one of the shots on the wall behind us, me arriving at Romanoff’s after the premiere for Helen of Troy the previous year in my white Grecian goddess gown, gold sandals, gold jewellery, real gold thread in my hair from the Welsh Valleys and spun into a beautiful diadem especially for me, reflecting my mother’s Welsh heritage. (Mummy was a vicar’s daughter from Berkhamsted, but the publicity department never allowed the facts to obscure a good story.) On one side of me stood Cliff Montrose, my co-star, and on the other, his arm around me, Joe Baxter. ‘Look at you, my dear,’ Gilbert said. ‘Many more such nights to come, I’m sure.’

His hand lightly pressed my arm, and I gazed up at him.

When the studio ‘suggested’ we go on a date together, I’d leapt for joy with excitement, but then demurred. It was well known in Hollywood that Gilbert Travers had a drinking problem. Margaret Heyer, his second wife, had left him and gone back to England three years ago; Confidential and Photoplay had still been full of it when I’d arrived here. He was a drunk; he beat her; she’d run out of the house naked, screaming, to be rescued by a zoologist who happened to be down on Wilshire Boulevard – which was a neat coincidence as Margaret Heyer’s latest film was about a young wife who goes to the Congo and falls in love with a zoologist. (The publicity machine at work again; Hollywood wasn’t ever that original in its ideas. Even I’d learned that, by then.)

But I thought about it some more and I felt sorry for him. I couldn’t help it. Gilbert had enlisted the day Great Britain went to war with Germany, had seen his friends killed, had caught dysentery and nearly died, and had come back to Hollywood to find film stars who’d never fought a day in their lives playing war heroes and lapping up the adulation of an admiring public. He never talked about the war to me, and after a few cock-eyed attempts to find out more, which he rebuffed angrily, I never asked him again. I understood, at least I thought I did. We both had secrets, things we weren’t to tell each other, and it was for the best.

The cocktails arrived and Gilbert lit our cigarettes. ‘Well, my dear,’ he said. ‘This is quite a red-letter day. Our house, us together. Are you excited?’

I looked around nervously. If the wrong people found out we were going to be living in sin, even if only for four weeks, it would be the end of my career. I’d laugh, afterwards, at how hypocritical it all was: what actually went on in this city while the proprieties were so slavishly observed. The studio, and Mr Featherstone, had spent hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars on my image, the perfect English rose. If Louella or Hedda, or some other unfriendly source, should be close by and should overhear, all hell would break lose. ‘Yes, of course, dear,’ I replied. ‘But – do keep your voice down.’

Gilbert clinked his glass against mine, his thin moustache twitching above his lip as he smiled. ‘You’re too concerned with appearances, Eve dear. We’ll be married as soon as the shoot’s over. And anyway, goddammit – you’re a star. They can’t touch you.’ He gulped most of his drink down and put his huge hand on my thigh. ‘Hm?’

‘Miss Noel …’ A photographer appeared, flanked by Mike and one of the doormen. ‘Coupla shots, please?’

‘Of course,’ I said, smiling slightly. One had to be polite to the press, no matter how much the inconvenience. And the story of the quintessential English gentleman actor, once at the top of his game but mentally scarred by war, brought back into love and life again by a young English beauty, star of the highest-grossing picture of 1957 and heroine of every fan magazine, was proving to be addictive to the American public. They lapped us up, Gilbert and me. The studio, and Gilbert’s new agent, fed the magazines and the radio shows a soapy romance about how I’d lured him out of his shell, taught him how to laugh again, and he had protected me, a young shy ingenue, from the bear pit that was Hollywood. It was a little ridiculous, sure, but I rather wanted it to be true, too. My old life – oh, it seemed as if someone else had lived it and then told me about it: a memory acquired elsewhere, not my own. My parents, the house by the river … Rose, her great fits of anger, her death, and my life without her – all solitary, sad, strange – and then my time in London, so much fun and so different again from this life here. Back in England, I had grown up feeling lost without Rose. I was working towards something unattainable. The reward was satisfaction of a job well done. Here, you just had to smile, and people told you how wonderful you were.

Gilbert put his arm around me. I moved against him, hoping he wouldn’t crush the black silk birds that perched on each shoulder of the heavy cream silk dress. We paused for the photograph, holding our cocktail glasses high, heads touching, smiles wide. All of Gilbert’s teeth had been replaced by a zealous MGM in the thirties. Five of mine had been capped, but that was the least of what they’d done to me since I’d been here.

‘Anything to say about the rumours that you guys are headed for the altar?’ The photographer licked a pencil and took out a pad.

‘We couldn’t possibly comment,’ Gilbert said. ‘However, Miss Noel and I greatly enjoy each other’s company.’

‘Gilbert, how does it feel, stepping out with Hollywood’s biggest new star?’

‘She’s just Eve to me,’ Gilbert said. ‘You have to understand, Sid. When we’re together, such considerations aren’t relevant.’ He signalled for another drink.

‘Eve, Eve – what’s next for you?’

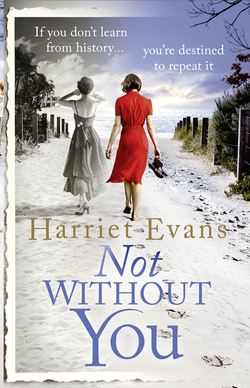

I paused, and blinked several times, smiling sweetly as if flattered by the attention; humble. ‘I’m making a wonderful picture, Sid, with Conrad Joyce, which I very much hope the movie-going public will enjoy. Lanterns Over Mandalay. It’s about a nun during the war, and it’s a most powerful story.’

‘She’s going to be absolutely wonderful in it,’ Gilbert said warmly. ‘Just wonderful. Aren’t you, darling?’

‘And Eve, you and white roses – are they still your favourite flower? You’re famous for it!’

My throat tightened; I felt hot, trapped behind the table, fixed to the floor. ‘I—’ I began.

‘No, Sid,’ the doorman said firmly. ‘Three questions. We told ya.’ He grabbed the photojournalist by the scruff of the neck and steered him past the tables and out through the door.

I breathed out. ‘Gosh,’ I said, taking another sip of my cocktail.

Gilbert said nothing, but stubbed a cigarette out viciously into the wide crystal ashtray, then immediately lit another.

‘Darling, what would you like to eat?’ I asked.

No answer.

‘Gilbert—’

‘You could have mentioned Dynasty of Fools,’ Gilbert said. He sucked on his cigarette tartly, his nostrils flaring. ‘I backed you up. You should have done the same for me.’

‘Oh,’ I said, appalled. ‘I’m sorry – darling, I didn’t think.’ I shook my head and tried to slide out of the banquette. ‘I’ll go and tell him how good you are, everyone’s saying so—’

‘Forget it.’ His hand was heavy on my shoulder, pushing me back down. ‘Forget it. You couldn’t be bothered to remember then so what’s the point now?’ There was a ripping sound. ‘Oh, this damned fool dress.’

I looked in agony at the little black silk bird on my shoulder, torn and dangling, its beak almost in my armpit. ‘It’s fine,’ I said, though he hadn’t said anything. ‘Perhaps I should just—’

Gilbert tutted in impatience. ‘Here.’ He wound the thread around my shoulder, tugging it tight, pulling the bird back into position again. ‘Damn it, I’m sorry, Eve. Shouldn’t have lost my rag like that, darling. Forgive?’

I smiled at him; he looked flustered and annoyed. ‘Of course, forgive,’ I said.

‘You’re a wonderful girl, you know that.’ He kissed me lightly on the shoulder.

We were unnoticed at the back of the room. I kissed him back on the lips. ‘You are a wonderful, wonderful man,’ I told him softly, relief flooding through me. ‘I can’t quite believe my luck.’

And I couldn’t, really. One part of me knew it was a good idea, this cooked-up romance with Gilbert Travers. Everyone benefited. The other part, the part I hadn’t told anyone at the studio about, was the twelve-year-old me, swooning over Gilbert Travers at the Picturehouse in Stratford, watching his films week after week in the lean years after the war where they showed old thirties fare again and again. He was a schoolgirl fantasy to me. The only crime I had ever committed in my short, boring life was that once I had sneaked into the library and cut a picture of Gilbert Travers arriving at Quaglino’s out of the Illustrated London News. And he was here, by my side – he was mine, and that was worth a hell of a lot of ripped birds, I supposed.

‘I don’t know how you put up with me,’ he said, shifting in his seat, still slightly red. ‘I’m a brute.’ His mouth drooped, his eyes were filmy. ‘A foul-mouthed, boozy, moody, selfish brute. You’d be happier if I let you go and find someone else. I’m more than twice your age, for God’s sake.’

‘You’re forty-eight, and I’m a grown woman, darling,’ I told him. ‘I know what I’m doing.’

In truth, I did dread his moods, which came without warning, throwing a black cloak over a perfectly nice evening. He could sit there and say nothing for hours, with me darting around him like a sparrow – Would you like another drink? Here’s the paper, darling, I thought you’d like to see this. Oh, by the way, I ran into Vivian at the studio today, and he says you’re marvellous in Dynasty. Everyone’s talking about it – working harder and harder to bring him back into the room. I was too afraid to call his bluff. I didn’t know what happened if you did, in any situation.

I wish I’d learned then that when you call someone’s bluff you usually win: it’s simply not what they’re expecting. And swimming along in the slipstream of another person’s current is no way to live.

It was then that I looked up and saw someone, staring at me from the other side of the room. What would have happened if I hadn’t? What if I’d never seen Don Matthews again? Would Gilbert and I have continued our evening and would it have been lovely? Would everything have worked out differently?

‘Excuse me, darling,’ I said. ‘Let me go and fix my dress. I’ll be straight back.’ I squeezed his hand and stood up, and as I walked out towards the terrace Don turned and saw me. He whispered something to his companion and left the bar.

‘Well, well. Miss Avocado 1956,’ he said, shaking my hand.

‘Don,’ I said, clasping his fingers in mine, tilting my head to meet his dark, warm gaze. ‘It’s good to see you. How are you?’

‘I’m the same, but you’re much better,’ he said, looking me up and down. ‘Congratulations. You were – well, I thought you wouldn’t make it. I thought you’d crack and go back home to Mum and Dad.’ He said this in a terrible English accent.

I had the most curious feeling we’d last met only days before, not nearly two years ago. ‘I don’t give up,’ I said. ‘I wanted to be a star. I told you.’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Yes, you did. But you were different back then.’ He stared at me. ‘Gosh. What did they do to you?’

I stared at him. ‘Oh,’ I said, after a moment. ‘It’s probably my hair. Electrolysis. They thought I should have a widow’s peak for Helen. It was painful, but I suppose they were right.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘Not that.’

‘Or the teeth?’ I said, opening my mouth. ‘Five caps – it’s made a world of difference.’ He shook his head. ‘I lost a stone, too, which was terribly hard, but I needed to.’

‘No, you didn’t.’ He gave that sweet, lopsided grin I’d forgotten about. ‘Forget it. I’m looking for something that’s not there, I guess. You’re all grown-up, Rose.’

I’d forgotten he’d called me that. Rose. I started and he smiled again.

‘I know all your dirty little secrets, remember,’ he said. I must have looked as worried as I felt, because he added, ‘It’s a joke. Hey, don’t worry. I’m not one of those guys.’

‘I know you’re not,’ I said, and I knew it was true. ‘Anyway,’ I said brightly. ‘How are you? What are you working on at the moment?’

‘Something special,’ he said. ‘I’m polishing it up right now. About a girl from a small town who moves to the big city and gets lost. In fact, I had you in mind for it. I always have done, Rose.’

His eyes never left my face but I avoided his gaze. ‘How exciting. What’s the title?’

He paused. ‘Wait and see.’

‘That’s a great title.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘I mean, Rose, just wait and see. In fact, I’d like to be the one to tell you. Soon.’

‘Really?’ I said. I was embarrassed and I didn’t know why.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It’s for Monumental, and I think they’re talking about putting you in it after Mandalay’s done shooting. I’ll get you a copy.’

Typical that everyone else would know except me what I’d be doing next. My life wasn’t my own to plan; it was the studio’s, Moss Fisher’s in particular, and I knew it and was grateful to them. ‘That’s – great,’ I said. ‘Listen, Don—’

Gilbert appeared at that moment. ‘Darling, what are you doing?’ He stared at Don in that curiously hostile way that upper-class English people have. ‘Oh. Good evening.’

‘Mr Travers, a real pleasure to meet you. Don Matthews.’ Don held out his hand.

‘Don’s a screenwriter, darling,’ I said. ‘He wrote Too Many Stars.’

‘Ah.’ Gilbert could barely conceal his apathy. ‘Darling, I see Jack over there. I rather thought I might say hello to him. Excuse me, won’t you.’ He nodded at Don and strode off.

‘I don’t follow the fan magazines, I’m afraid,’ Don said. ‘That’s the guy they’ve set you up with? Gilbert Travers? He’s a little old for you, don’t you think?’

He tapped a cigarette on the side of a worn silver case. I watched him, rubbing my bare arms in the sudden chill of the restaurant. ‘He’s wonderful,’ I said. ‘We—’

‘You going to marry him?’ He rapped out the question, his voice harsh.

A commotion at the other end of the room forestalled my answer; a flurry of white floor-length ermine and flashing diamonds. I looked over to see Benita Medici, my rival at the studio, arriving on the arm of a suave, rake-thin man whom I knew to be Danny Paige, the biggest, wildest bandleader of the moment. ‘Oh, my goodness, Danny Paige!’ I said. ‘I just love him.’

‘I’m more of a Sinatra guy,’ Don said. ‘I like to listen at home. Too old to jive.’

‘Slippers and pipe and a paper by the fire, while your wife soothes your brow and fixes you a drink?’ I said. You don’t know anything about him. Why would you care if he’s married or not?

‘Something like that,’ he said, and he smiled again. ‘Only it’s hard for her to fix me a drink these days.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Why?’

‘Vegas is a long way away,’ he said. ‘Too far to commute.’

‘What does she do in Vegas?’

He waved his hand. ‘Doesn’t matter. She doesn’t do it with me, that’s the main thing. I’m not a great guy to live with. And I was a lousy husband. She made the right decision.’ He tapped the side of his glass. ‘I like to drink alone, so it worked out fine.’

I didn’t know what to say. ‘That’s so sad.’

‘Why?’ He smiled again. ‘Marriages fail all the time.’

‘But they shouldn’t,’ I said.

‘God, you’re young,’ he said. He jangled some change in his pocket. ‘You know, I worry about you, Rose. You’re such a baby. You shouldn’t be here, you know it? You should be back in England fluffing up an Elizabethan ruff and getting ready to go out on stage, not living this – life, like a gilded bird in a cage.’ His eyes scanned me, looking at the beautiful silk birds on my dress, the crooked one on my shoulder.

I laughed. ‘Don’t let’s disagree. Not when it’s so lovely to see you again.’ I looked over to where Gilbert was standing at the bar, a greyish-blue plume of cigar smoke rising straight above his head, like a signal.

‘Fine. Change the subject.’

‘What’s your favourite Sinatra album?’ I asked him.

Don whistled. ‘Gee. That’s hard. You like him too?’

‘Oh, yes, I love him too. More, in fact. He’s my biggest discovery since I came here. I’d never heard him before.’

‘You never heard Sinatra?’ Don’s face was a picture. ‘Rose, c’mon.’

‘We didn’t have jazz and … music like that, when I was growing up.’ My home was a quiet, forbidding house, full to me of the sound of echoing silence and my guilt which filled up the empty rooms, where once there had been shouts of joy, and more often screams of fury, thundering steps on hard tiles. When Rose was around there’d been no need for music.

‘Well, in London … of course. In the coffee bars, and at dances. Not before then.’ I shook my head, trying to remove the image of Rose singing, shouting, along to some song on the radio, her mouth wide open, eyes full of joy, with that intensity that sometimes scared me. She would have loved Sinatra. She loved music. I pushed the image away, closing my eyes briefly, then opening them. There. Gone. ‘I’m dying to meet him. Imagine if I did. Mr Baxter says he’ll fix it. We were in here once and he and Ava Gardner came in – I nearly died. I must have listened to Songs for Swingin’ Lovers around a thousand times. The record is worn thin. Dilly’s my dresser, and she says she’s going to confiscate it if she has to listen to it again.’

‘Well. In the Wee Small Hours is my favourite, since you ask. “I’ll Be Around”.’

‘Oh.’ I was disappointed. ‘But it’s so depressing. All those sad songs.’

‘I like sad songs,’ Don said. He looked over at Gilbert, then back at me.

My shoes were tight, and I rubbed my eyes, suddenly tired. It had been a long day, filming a gruelling scene in which Diana the nun hides out in a villager’s hut as the Japanese kill scores of people and retreat, setting fire to the village. My back ached from crouching for hours in the same position, and the tips of my fingers were raw and bloody from scrabbling at the gravelly, sandy earth (Burbank’s finest, shipped in from the edge of the Mojave Desert). ‘You OK?’ Don asked.

‘Just tired,’ I answered.

‘I’ll let you go. Just one thing, though. That white roses thing – why don’t you like them? I was watching you earlier. I saw your face when that reporter asked you about them.’

I stiffened. ‘What do you mean?’

‘The publicity guys made it up, didn’t they?’

‘Don’t let the fans hear you say that,’ I said, keeping my voice light. ‘I get about fifty a day.’ Mr Baxter’s publicity department put it out that Eve Noel the English rose missed her rose bush at home in England so much that she insisted on having white roses flown in from England for her dressing room, since when every day, to my home, to the Beverly Hills Hotel where I stayed on and off, to the studio, white roses arrived by the dozen. It was a sign I’d arrived, they kept telling me, as Dilly put armfuls in the trash or handed them out to girls on the set.

But I hated the things. Loathed them. They would always be linked for me with Mr Baxter in his car, hurting me, puffing over me, the feeling of his vile hands on me. The cloying sweet scent and the surrender I made that night; it was all linked. I tried never to think about that night, never. I assigned it a colour, cream, and if I ever was forced to think about it, like the time Mr Baxter tried it again, in my dressing room on set, or the time he and I rode in the same car after the premiere of Helen of Troy, I just thought about the colour cream all the way. I knew I’d done the right thing. I’d passed his test, and mine too, hadn’t I? Wasn’t I a star, wasn’t I adored and feted by millions around the world? So what if the sight of a few roses made me want to throw up.

Unfortunately for me, like all good publicity, sooner or later even those responsible for the myth in the first place started to believe it. Gilbert hated it too, because people were always trying to give me white roses, at premieres, at parties, wherever we went. Hostesses at dinners would thoughtfully always put white roses on the table and laugh a tinkling laugh when I murmured my thanks: ‘Oh, we know how you love them, dear!’

I shook my head, and said ‘Cream’ softly to myself. Don Matthews watched me.

‘Whose idea was it? The rose thing?’

I answered honestly, ‘Joe Baxter’s. I actually don’t like them.’

‘I thought so,’ he said. ‘He did the same with another girl he was trying to launch. Dana something.’

‘Really?’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Don. ‘He was obsessed with her.’ His voice was casual, as if he were giving me a piece of gossip from the studio, but something, something made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.

‘What happened to her?’ I asked, my heart beating at the base of my throat.

‘Oh, she was Southern, and he put it out that she missed the camellias from home. But camellias only last a day or two and they’re a real pain in the ass to get out here. And then the big picture he’d put her in flopped – do you remember Sir Lancelot?’ I shook my head. ‘Exactly. She was poison after that. They put her on suspension for something, then she made B-movies when her contract expired, then she disappeared. Last I heard she was addicted to the pills and making ends meet in titty movies out in San Fernando. Poor kid.’

I knew all about suspension. People kept saying the studios were on their last legs, but the truth was my contract with them was still rigid tight. They owned me. I’d heard about the actors and actresses who stopped being favourites. Too old, too expensive, too demanding. They’d be sent scripts that the studio knew they’d never agree to do – playing a camp comedy part, or an eighty-year-old aunt. When they turned them down, the studio put them on suspension, which meant they couldn’t work for anyone. And they could only watch as someone cheaper and younger, with better teeth and smoother skin, took their parts from under them.

I swallowed, as the noise of the bar and my own fatigue hit me in another wave. Don said softly, ‘Hey, kid, it’s OK. I’m just warning you. Don’t become another Dana. You’re on top of the world now, but they’ll still spit you out if you get to be too much trouble.’

I nodded.

‘Don’t let them make you do anything you don’t want to do. You promise me, Rose?’ And again he looked over at Gilbert.

‘I promise,’ I said, not really sure what he was talking about, but knowing he was telling me the truth. His lean body moved closer to mine; I watched the grazing of nut-brown shadowing his jaw, the tight expression in his eyes. ‘I’m OK, really.’

‘I know you are.’ He squeezed my arm. ‘We’ll talk about my script. I’ll come find you at the studio,’ he said, and I wanted to say ‘When?’ But Gilbert approached, with his arm round one of his friends, his third or fourth cocktail in hand. Danny Paige was tapping a rhythm out on the bar, someone was singing, the moon was shining outside and inside, tiny shafts of light spun from the crystal chandelier above us. The bird was still dangling from my arm, untended, unloved. I excused myself from Gilbert and went to the powder room. Alone in front of the mirror, I stared at my reflection for a long time, to try and see how Don thought I’d changed. I didn’t know why it mattered to me so much that he thought I had.