Читать книгу Alligators of the North - Harry Barrett - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 In the Beginning

When Columbus “discovered” America in 1492, the whole of northeastern North America was covered in forest. The aboriginals living there were primarily nomadic in nature, hunting and fishing and supplementing their food supply with the berries and fruits that grew in abundance. Those living along the north shore of Lake Erie were known as the Attawandaron, or as Champlain called them, the Neutrals, who traded with both the Algonquin to the north and the Iroquois of the Mohawk Valley to the south. The Petuns, or Tobacco Indians, occupied lands southeast of Lake Huron, so called because they grew tobacco, which they traded as far west as the Pacific coast. These people lived in more permanent villages, growing corn or maize, beans, and squash, as well as pumpkins, sunflowers, and potatoes. As soil fertility declined, they would simply move on and develop a new site.

In the mid-1600s, the Neutrals were driven from their traditional lands. Those who survived were absorbed into the Wyandotte Nation, west of Lake Huron. The north shore of Lake Erie, referred to today as the Carolinian Forest Zone, was vacant and known as the Iroquoian beaver-hunting grounds, land that the British coveted for settlement. By the 1790s, when Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe was charged with bringing white settlers to what was known by then as Upper Canada, the area had been taken over by the Mississauga from north of Lake Ontario.1

The early settlers, many of whom were United Empire Loyalists, took up lots along the lakeshore as the lake proved to be the major access to the outside world. Roads were slow to develop and those that did exist were little more than rough, single-track forest trails in the early days of development. Simcoe encouraged men who had served in the British forces to settle in Upper Canada, as he wished to ensure a large complement of able settlers trained in the art of war and loyal to the British Crown as members of the local militia units. Simcoe did not trust the Americans, and as the War of 1812–14 demonstrated, his fears were well-founded. An enlisted man received one hundred acres of undeveloped, forested land for free, whereas captains, like Samuel Ryerse, founder of Port Ryerse, or his brother Joseph Ryerson, were granted twelve hundred acres each.

To keep his grant of land, a settler was required to clear a given amount annually, thus to many, the forest and its tree cover were considered the enemy. In many cases trees were cut and piled up to be burned, just to get rid of them. For those trees cut into logs, methods of sawing them into lumber were slow and primitive. Many were squared into beams using a broad axe, however, too many more were burned or left to rot.

As early as June 7, 1797, an official document reported to the admiralty that white pine with a diameter of 3 feet and a height of up to 175 feet existed, pine that was ideal for masting British ships. In Walsingham Township, Norfolk County, alone, 124 lots were listed with pine suitable for masting and 22 lots with oak suitable for use by the Royal Navy. This report is in the handwriting of Land Surveyor Thomas Welch of Vittoria, and titled “Report of Masting and Other Timber Fit for the Use of the Royal Navy, in the Township of Walsingham.”2 Subsequent pages in the document list suitable pine and oak in Charlotteville and Rainham townships. The best of these stands were marked, or blazed, with the King’s Mark. Once marked, no logger dared cut this timber reserved for the exclusive use of British fighting ships.

In the mid-1830s, William Pope,3 an English immigrant wildlife artist who lived in the area, commented on the miles of dark, gloomy forest as seen from the lake while sailing from Buffalo westward to Kettle Creek (Port Stanley). He also commented on the poor state of the few roads in the country as well as the fact it was almost impossible to move through much of the heavily forested country, when hunting with his fowling piece, because of the tremendous number of deadfalls blocking a person’s progress. Few inroads had as yet been made into the interior forested areas of southern Ontario.

Many sawmills were being built along the streams and rivers using waterwheels as their source of power. Most of these were smaller operations, however. With the advent of the steam engine, the mill owner was no longer dependent on a good flow of water and had unlimited choice for the ideal location of his mill. By 1851, there were thirty-eight sawmills in Bayham Township, Elgin County, alone, producing 25,570,000 board feet of sawed lumber.

Slowly changes were taking place. The schooner traffic was increasing on the lakes, aided by the building, in 1825, of the Erie Canal from Buffalo to the Hudson River and some ten years later the building, in 1836, of the Welland Canal. With the opening up of our waterways came the improvement of navigational aids and harbour facilities generally. Better loading and unloading methods were being devised to handle the growing surplus of logs, lumber, shingle blocks, stave bolts, livestock, and grain being produced for shipment by a burgeoning population. The Erie Canal provided a new market and route for southwestern Ontario pine to the eastern seaboard of the United States. The Welland Canal, in turn, provided a route through Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City, and the export of timber to Great Britain.

It was about this time that a Scottish deep-sea clipper-ship captain, who had commanded his own ship on the seven seas, retired in Port Dover, Norfolk County, on Lake Erie. His name was Captain Alexander McNeilledge. Excerpts from his diary give the reader a unique insight into the lumber industry on Lake Erie as it existed at that time. Some entries from 1845 to 1867 follow:

Winter, 1845 — Number of teams drawing timber on the plank road for the [construction of] Harbour and timber to ship off [to Buffalo etc.]

Spring, 1845 — Steam boat “Kent” came in [to Port Dover] to tow Mr. Cummings timber rafts down to the Grand River to go to Quebec. (via the Feeder canal.) Number of vessels in, one timber Brig layd up.

Spring, 1845 — the vessels went out this morning bound up to [B]ear Creek for timber … The Schooner “Linnie Powell”, Capt. McMannis, left for St. Catherines to get fix’d for Carring timber … Schr. “Cleopatra” from Buffalo in sight, got foggy, — ringing the town bell to guid her in.

May 25th, 1845 — I send a little parcel and letter to Captain Zealand, of Hamilton, his Schr. The “Union” being ready to sail from here for Liverpool, [England]. Cargo Staves and oak timber being the first vessel direct from this Port.

Sunday, August 7th, 1859 — Took dinner on board the Brig “Ocean” with Captain Garie … they have two horses on board being a lumber or timber vessel owned by Mr. Waters [of Port Dover]. [The horses would be used for working the capstan etc. in loading and unloading the timber.]

Monday, August 8th, 1859 — Brig “Ocean” loading square timber for Kingston.

September 22nd, 1860 — Brig “Ocean,” Canadian, capsized in a gale off Rondeau, with a cargo of lumber. A total loss. Crew formed a raft and after 36 hours were picked up.

August 14th, 1863 — Captain Guskin of Bark “Mary Jane” up from Kingston loading timber at [Port] Ryerse & finish loading here for Kingston. I intend taking trip in her.

August 6th, 1866 — Mr. Lees gone to Chatham, the “Mary Jane” being thare loading timber for Tenawanda. Vessels loading barley, 58 cents/bus., for Buffalo. Square timber coming in.

January 26, 1867 — Good many Sleighs knocking round large square timber, Staves & Shingle blocks …

February 17th, 1867 — Many sleighs, large sticks of timber & Spars & Staves coming in.

April, 1867 — “Mary Jane” at anchor off the pear [pier] takeing (sic) in timber, rather rough.4

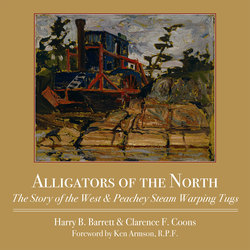

The white pine shown here is typical of that found on the Long Point Country sand plain.

Courtesy of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, E.J. Zavitz Collection.

Among the many experienced sawyers coming into the Norfolk sand plain at this time was Collin LaFortune, who settled in the Big Creek valley of Walsingham Township in 1836. During his first winter he helped cut four hundred masts from pine each 4 feet or more in diameter. These were hauled to Big Creek by oxen and floated to the Inner Bay of Long Point for assembly into rafts, to be towed to Buffalo for export.

In 1845 LaFortune reported helping cut one of the longest masts on record from near Walsingham Centre. The tree was perfectly straight and produced a mast 110 feet long without a knot, limb, or blemish of any kind. The largest pine LaFortune ever cut was from the same area and was 7 feet in diameter and 90 feet to the first limb. Because of a small, 3-inch hollow at the top of it, it was declared unsuitable for a mast and cut into logs for shipment to Buffalo. It was declared that in the whole of both Upper and Lower Canada there was no white pine of better size or quality than that to be found in the valleys of Big and Venison creeks in the Long Point Country.

Exports of sawed lumber from Port Burwell in 1846 were about 3 million board feet, and in three short years exports had increased to 8,424,154 board feet. Demand for imports was increasing dramatically as pioneer families became more affluent. Shipping firms prospered with their schooners carrying valuable cargo both in and out of the country.

The demand for logs and wood products was generally on the increase and methods of harvest and skidding were improving to the point where Canadian virgin stands of timber began to disappear at an alarming rate. Typical of this change were the actions of two young American fur traders for the North West Company, named Farmer and DeBlaquierre, who came into Canada from Buffalo to assess the potential for trade in furs in the Long Point Country. As they travelled the virgin wilderness they realized the tremendous potential for profit in the burgeoning lumber business.

In 1847, they returned to Woodstock in Upper Canada and began buying up lots, primarily in Walsingham Township, with heavy stands of virgin white pine. They soon had assembled some 20,000 acres of forested lands. They next mortgaged these properties to an American bank. In 1848, Farmer and DeBlaquierre used the proceeds from this transaction to build a large sawmill on Big Creek in the hamlet of Rowan Mills, on 6.5 acres purchased from William Franklin in Lot 7, Concession 1, of Walsingham Township. This steam-operated mill was capable of sawing 6 million board feet of prime lumber annually. The mill operated for nine years under the original owners until 1857 when DeBlaquierre sold it to Arnold Burrowe, a local mill operator.

Another prosperous operation was carried on at this time by the Laycock family, who had come originally from Buffalo to Cultus in Houghton Township, Norfolk County. To expedite the movement of logs from their forested properties they built a wooden-railed railway from Cultus to Big Creek. As the logs were cut they were drawn to their railroad and loaded on flatbed cars, to be drawn by horses to the bank of Big Creek. Here they were tipped into the water to be floated to the Inner Bay of Long Point, where they were made up into huge log booms and towed by steam tugs to Buffalo. A sawmill at Tonawanda, New York, was equipped to saw logs up to 80 feet in length.

It is of interest to note that by 1851, the newly established County of Norfolk had over six hundred people employed in sawmill operations and the County boasted three times as many sawmills per capita as the average number province-wide.