Читать книгу The Frontman - Harry Browne - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 IRELAND

‘WHAT A THRILL FOR FOUR IRISH BOYS FROM THE NORTHSIDE OF DUBLIN …’: ORIGINS

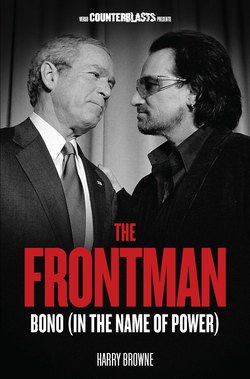

Bono is rich: he wears designer clothes, flies around in private jets, drives any one of five luxury cars, loves the finest of food and wine – his net worth has been estimated at more than a half-billion dollars.

Bono is famous: he fronts the most consistently popular band of the last three decades, has millions of fans, sings several of our era’s best-known songs – he wears sunglasses that draw attention to him rather than deflect it.

Bono is powerful: his counsel is sought, heard and heeded at the very highest levels of national and international governance – he is, as the Ramones might say, friends with the president, friends with the pope.

But Bono wants you to know he hasn’t forgotten where he comes from. As thousands gathered on Washington’s Mall in January 2009, and millions watched on TV, he told the man who would be inaugurated as US president two days later: ‘What a thrill for four Irish boys from the northside of Dublin to honour you, sir.’

When Bono, preening for Barack Obama and the wider world outside the Lincoln Memorial, chose these words of pseudo-self-deprecation to capture the all-round awesomeness of U2’s presence, he was indulging in a mashup of signifiers, typical of those who carefully craft their own images. At its most basic level, the ‘What a thrill for …’ was just an adaptation of American Dream boilerplate, which was flowing especially thick in those Obama-worshipping days: ‘We were just four Irish boys’, was what he meant, ‘and now look at us.’ ‘Irish’, though, doesn’t necessarily signify a foreign nationality for many people in the US, so much as a certain kind of Americans, or even just a bout of bad temper. However, Bono did throw in a few extra words of geographic specificity – ‘from the northside of Dublin’ – and in context one got the impression it was the realm of the working class, the baddest part of town. And it probably doesn’t hurt that ‘north’ and ‘Irish’ may also conjure up memories of old TV news footage of bombs and barbed wire. Suddenly, Bono, Adam, Larry and The Edge are cast in the mind’s eye as street urchins who dodged the crossfire of the Irish Troubles and lived to sing about it. Hey, didn’t they call two of their first three albums Boy and War?

This discussion of origin-mythmaking is not simply meant to suggest that Bono and his band are somehow inauthentic (though it is true that the concept of ‘authenticity’ and its discontents have stalked U2’s career). Nor is it meant to provoke the arguably racist questioning of ‘how Irish are they really?’ beloved of some hostile commentators, who point out that ‘Paul David Hewson’ bears no trace of Gaelic origins – but the same can be said about the names of millions of people who are unquestionably of Irish origin.

It is meant to disentangle the facts of Bono’s life from his rhetoric. In Dublin, the often-capitalised Northside and Southside are states of mind as much as states of geography, and are class signifiers to such an extent that, for example, the working-class Liberties south of the river Liffey are often described as ‘not really Southside’; similarly, the seaside urban villages of Clontarf, where Bono and the boys met at Mount Temple Comprehensive School, and Malahide, where Adam and The Edge lived as kids, are posh enough to be rhetorically exempted from the Northside that abuts them.

To be fair, we have no idea whether the word ‘northside’ carried a capital N in Bono’s mind’s eye when he drawled it outside the Lincoln Memorial. However, there’s no doubt that’s the way it was heard in Ireland: the Irish Times, quintessential Southside newspaper, devoted a column after the Obama affair to the trashing of Bono’s claim to real Northside-icity. (It is one of the small ironies of Dublin’s division that it is generally Southsiders who are most protective of the Northside and Real-Dub – ‘real Dublin’ – brands, treating them like Appellations Controlées, the guarantees of regional authenticity on bottles of French wine, denouncing any suspiciously middle-class figures, of whatever geographic origin, who attempt to wear the labels as badges of street-credibility.) Bono, it seems, with his unDubby mid-Atlantic accent and his mansion overlooking the most-definitely-Southside Killiney Bay, is forever to be condemned for alluding significantly to the fact that he grew up, genuinely, on the northside of Dublin city.

That Irish Times columnist remarked: ‘It’s not as if most of Bono’s friends are either dead or in jail. Last time I looked, they were making soundtracks and bowls.’1 This rather strangely and cleverly inverted put-down perhaps says more than it intends to about how the Irish Times sees the essence of Northsidedness – ‘dead or in jail’, like something out of a rapper’s boast about his unlikely rise from the streets. But it also helps us to get a handle on how misleading, or at least inadequate, Bono was being when he summarised U2 as ‘four Irish boys from the northside of Dublin’, a description that in the circumstances certainly signified (to listeners and viewers of whatever sensitivity) origins distant and isolated from centres and moments of cultural power like the one he was enjoying on Washington’s Mall, whether or not it signified full-blown poverty and deprivation.

The reality is that Bono grew up in a middle-class (that term is more upmarket in Ireland and Britain than in the US) and slightly countercultural enclave of the poor and working-class north Dublin area called ‘Ballymun’ (another signifying Appellation Controlée that he is occasionally abused for employing). ‘Violence … is the thing I remember most from my teenage years’, he has said, but without giving any more detail than a suggestion that, when he and his pals strayed into working-class territory, it was, you know, kind of scary.2 Ballymun’s notorious, now-demolished tower blocks may have been evoked in Bono’s ‘Running to Stand Still’, but he grew up a safe distance away on Cedarwood Road, full of comfy semi-detached homes with nice gardens, lawns and driveways.

In the early 1990s Bono tried to convince an American journalist, Bill Flanagan, that as a child he used to hustle tourists in (Protestant) St Patrick’s Cathedral:

‘I would charge them for tours of the cathedral’, [Bono] says. ‘I made good money.’

‘Oh’, I say, ‘you were an urchin.’

‘I was!’ Bono says brightly, at which [Bono’s wife] Ali bursts out laughing. She knows her husband never urched.3

Bono was no child of the streets; nor were the city and country he inhabited the complete backwaters that they look like in so much retrospection. Born in 1960, Bono was raised in a Republic of Ireland that was economically and culturally emerging from the isolation of the first four decades after independence. Emigration had slowed very dramatically, and with a new economic strategy of seeking foreign investment, the country was even attracting families from Britain like those of Bono’s future bandmates: Edge’s dad was an engineer, Clayton’s a pilot – higher earners than Bono’s father, with his white-collar job in the postal service. The sometimes-maddening tendency of the Irish economy to be out of sync with its neighbours was occasionally a good thing: for example, while Britain went slouching toward the Winter of Discontent in the late 1970s, Ireland, including the boys of U2, enjoyed a mini-boom.

New political winds were blowing through the era too: a leading politician could credibly claim that ‘the Seventies will be socialist’; there was a vigorous women’s liberation movement that got a good airing in broadcast and printed media; and there was of course a civil rights movement and ‘armed struggle’ across the border in British-controlled Northern Ireland. By the time Bono was starting secondary school at the new, liberal, Protestant-run, multi-denominational, co-educational Mount Temple, one of Britain’s favourite blues guitarists was Cork-based Rory Gallagher, and within another year or two Thin Lizzy – with a black Dubliner, Phil Lynnott, as frontman – were blasting up the rock charts on both sides of the Atlantic. And that’s to say nothing of the centrality of Irish music and musicians in the ongoing international ‘revival’ of traditional and folk music. Ireland wasn’t rich, but it was a reasonably cool place to be from, and in, with nothing much cooler and more connected than to be a teenage rock ’n’ roller at Mount Temple, with its largely well-off student body. When 1977 came along, some of the punk bands made it to Dublin on tour.

You might call them cosmopolitan provincials, or provincial cosmopolitans; either way, middle-class young people in Dublin in the 1970s were capable of being clued-in about the wider world, and even feeling that they could exert some influence over it. Pirate radio and a TV aerial that could pick up the BBC meant that you needn’t miss a thing. In 1977 Niall Stokes launched an ambitious and specifically Irish title, Hot Press, an irreverently liberal music magazine, which quickly turned into a must-read for local fans and bands alike, especially in Dublin.

Ah, but there was, of course, the power of the Catholic church to spoil all that, and for many people it was a terrible scourge on their lives. Its role shouldn’t, however, be exaggerated, as it often is in the memories and polemics of those who get over-excited about Ireland’s eventual liberation from its yoke. While it was true that the Catholic hierarchy cast a long shadow, including over national legislation on matters such as divorce and birth control – U2 would eventually play their first benefit gig in 1978 for the Contraception Action Campaign4 – it didn’t especially darken places like Mount Temple.

Bono has made much of his parents’ religiously mixed marriage: ‘My mother was a Protestant, my father was a Catholic; no big deal anywhere else in the world but here’ – benighted Ireland, the only place in the world where denominational differences matter. Except that Bono has never shown that his parents’ mixed marriage was anything like a ‘big deal’ in the circles he inhabited. Indeed, it is striking that in an Ireland where the Catholic church’s Ne temere doctrine of 1908, ruling that children in mixed marriages must be raised Catholic, had been declared by the Supreme Court in 1950 to be enforceable in law, Bobby and Iris Hewson felt free to make their own arrangements: they agreed to raise their children alternately, the first Protestant, the second (Paul, later to become Bono) Catholic – or, by another telling, boys Catholic and girls Protestant – and then didn’t stick to that arrangement in practice, with Bobby leaving their two boys in their mother’s (Protestant) spiritual care. Young Paul went to mainstream Protestant primary schools.5

The Hewsons’ mixed marriage, and whatever agonies they may have suffered because of it, is of course a private matter; it may well have been harder than we’ll ever know. No one would dream of questioning the real trauma and loss that accompanied Iris Hewson’s death when young Paul was fourteen. But it is difficult not to suspect that Bono locates himself as a childhood victim of sectarian pressures at least partly to associate his origins with the conflict in Northern Ireland, understood in much of the rest of the world to be a sectarian Protestant-versus-Catholic war. Bono’s repeated insistence that he had a little piece of the war in his very own childhood home – he had, he said in a Washington speech in 2006, ‘a father who was Protestant and a mother who was Catholic in a country where the line between the two was, quite literally, often a battle line’6 – is part of the backdrop to his decades of posturing on that conflict. (Strangely enough, in that speech he reversed his parents’ actual religious affiliations.) In reality the Troubles took place almost in their entirety sixty-plus miles up the road in Northern Ireland; and when the conflict made rare, bloody intrusions into the Republic, it didn’t discriminate between Protestant, Catholic and ‘mixed’ victims.

The four boys in U2, meanwhile, were not very different from most of the people who would become their fans across Europe and North America: comfortably off, liberally raised, and drawn inexorably to the international language of rock ’n’ roll. Somewhat more unusually for teenagers at that time and in those circumstances, Bono and his mates were attracted by another global language: that of Christianity.

DANDELION MARKET: U2 EMERGES

In many ways, their enthusiasm for Jesus was more outré and cutting-edge than their musical aesthetic. Under their first two names of Feedback and The Hype, the band that would become U2 played covers of songs by middle-of-the-road chart acts such as Peter Frampton, the Eagles and the Moody Blues well into 1977 – many months after the Sex Pistols had released ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and the older fellas in Dublin band the Boomtown Rats had headed off to join the punk scene in London. When young Bono wrote his first song, ‘What’s Going On?’, he apparently didn’t realise that Marvin Gaye had got to the title first. Only after the Clash came to town in October 1977 did the band begin to punk up their sound and their look, and finally their name.7

Paul Hewson grabbed his own stage-name not from any Christian commitment to doing good but from a prominent hearing-aid shop in central Dublin that advertised ‘Bono Vox’ (good voice) devices. (The name is pronounced, as one of his detractors notes, to rhyme with ‘con-oh’ rather than ‘oh-no’.8) His youthful religious explorations began at an early age, when he befriended neighbour Derek Rowan (later to become ‘Guggi’, a successful painter), who belonged to an evangelical Protestant sect that had been founded in Dublin in the 1820s, the Plymouth Brethren.9 The intensification of his religious curiosity, at home and in school, has been attributed to the loss of his mother when he was fourteen; when Larry Mullen’s mother died a few years later, the two teenagers delved together into Bible study. Religious observance was high in Ireland, among both Protestants and Catholics; religious identity was important to a substantial portion of the population; but religious enthusiasm was and is seen as a distinctly odd phenomenon in the Republic. Back in the 1980s many Irish observers would wrinkle their noses in suspicion and tell you that U2 were ‘some kind of born-agains’ – the phrase suggesting an Americanised Protestant evangelicalism. Or, on the other hand, they would raise eyebrows and explain that U2 ‘had gone charismatic’ – a term which, unlike ‘born-again’, pointed to the possibility of a basically Catholic orientation, but one far removed from the quietly muttered rituals that dominated most Irish-Catholic practice.

Ireland is a country where you can still be half-seriously asked if you’re ‘a Catholic atheist or a Protestant atheist’, but most Irish people seem to have lost interest long ago in whether Bono and two of his bandmates (bassist Adam Clayton stayed out of the Bible scene) were or are Protestant Christians or Catholic Christians – though the interest in scripture points to the former. The prayer group they joined in 1978, and eventually left more than three years later when they came under pressure from fellow members to abandon rock ’n’ roll and its trappings, was called Shalom; but, despite the name, Shalom’s members were not Jewish Christians, and, just to add to the confusion, the organisation has been described as both ‘evangelical’ and ‘charismatic’, with ‘Pentecostal’ thrown in for good measure.10 Bono’s wedding in 1982 was conducted in the conventionally Protestant Church of Ireland – part of the Anglican communion – to which his wife Ali Stewart belonged, but with some of his friends’ Plymouth Brethren colouring thrown in.11

Whatever words you use to describe the band’s early Christianity, it doesn’t appear to have made much of a mark on the Dublin music scene. In February 1979 Bono told Hot Press writer Bill Graham about the religious commitments of his circle of friends in the earnest, creative, post-hippy imagined community they called Lypton Village, ‘One thing you should know about the Village: we’re all Christians.’ Graham, however, chose to leave that revelation out of his published interview with the band he was already growing to love, in order to protect their reputation.12 Oddly enough, U2 were apparently stalked for a few weeks in 1979 by a group of young toughs from Bono’s neighbourhood styling themselves the ‘Black Catholics’, who denounced U2 as ‘Protestant bastards’. But this seemingly had more to do with class than religion – ‘Protestant’ translated in this case as ‘posh and stuck-up’; and after a couple of tussles the harassment was ended by Bono marching down Cedarwood Road to confront the daddy of one of his persecutors.13 The Christians of U2 weren’t, in any case, persecuted for their religious beliefs; nor did they make much of proselytising them.

But even as U2 were embracing God they came face to face with Mammon, in the form of Paul McGuinness. Bono has described U2 as ‘a gang of four, but a corporation of five’,14 with the fifth and equal partner being the hard-headed capitalist who has managed the band from nearly their start. McGuinness, a decade older than the band, was and is a traditional Irish Catholic, which is to say a man without a shred of obvious, let alone ostentatious, Christianity. (He famously shot down the band when they were hesitating over a set of gigs, under pressure from Shalom comrades: ‘If God had something to say about this tour he should have raised his hand a little earlier.’15) From the time he took on management of the band after passionate encouragement from Graham of Hot Press, McGuinness served the purpose of deflecting and absorbing criticism: he could be a tough, obsessive bastard so they didn’t have to. He aroused far more resentment among other musicians than anything involving U2’s religion ever did. One false rumour doing the rounds in 1979 suggested that McGuinness made a phone call pretending to be a London A&R man in order to get U2 a gig opening for the popular English New Waver Joe Jackson, insisting that local rivals Rocky De Valera & the Gravediggers had to be dumped so he could see U2. (That change was never in fact made.) When Heat magazine printed the untrue rumour, McGuinness initiated a lawsuit that soon shut the magazine down.16 McGuinness was a man who was tough enough to attract conspiracy theories, and dealt firmly with adversity.

Commercial success didn’t immediately follow upon McGuinness’s manoeuvres, but his ambition and U2’s discipline meant that they left no stone unturned. Ireland was, unbeknown to itself, coming to the end of its era of the showbands, typically eight-piece sharp-suited groups who toured the highways and byways playing cover songs for dancing. These bands were still, in 1979, making more money than the small collection of post-punk groups like U2 that constituted an incestuous Dublin scene. The Boomtown Rats were big, but their profits seemed to underline the truism that London was where the action was. McGuinness eventually took his ‘Baby Band’17 to play in London, but built them up even to London journalists and industry scouts as Dublin’s quintessential live act. He got them signed to a small, non-exclusive deal with the CBS subsidiary in Ireland, and built their live following remorselessly, putting on a famous series of Saturday-afternoon shows in the half-derelict Dandelion Market next to St Stephen’s Green to cater for U2’s under-eighteen following, who couldn’t go to pub and club gigs. The shows at the ‘Dando’ would become the stuff of legend: few Dubliners of a certain age will admit to having not seen them there, though a few will tell you they were rotten. The climax of McGuinness’s efforts came when – as something of a last throw of the dice – he booked them to tour Ireland and to play the National Stadium on Dublin’s South Circular Road. ‘National Stadium’ is a grand name for a boxing venue that seated a couple of thousand people, but McGuinness put them there knowing full well that they couldn’t possibly fill it: top international acts sometimes failed to do so. Sure enough, there were hundreds of empty seats when U2 took the stage on 26 February 1980, but the declaration of importance and ambition of that winter was enough to seal a good deal at last with Bill Stewart – a British army intelligence officer turned ad-man turned music scout – on behalf of an international label, Island Records, which had made its fortune with Bob Marley but, according to Graham, was a bit at a loss when it came to the current state of rock.18

That was okay, because U2 didn’t sound like they had much of a clue either. Listen to the first U2 singles and you may find it hard to believe that this is a ‘great’ band working in the aftermath of, say, the Clash’s London Calling – released a few months before U2 signed with Island. Musical range, lyrical wit, political sensibility: U2 had none of the above. They were, it’s true, still young, five or six years younger than the youngest members of the Clash, but youth alone doesn’t fully explain just how callow they sound. It’s easy to conclude that this is an Eagles cover-band that picked up some pace from punk and some posturing from David Bowie but simply hadn’t listened to enough good, passionate music to understand how it might work technically and emotionally. Their devotion, meanwhile, to what authors Sean Campbell and Gerry Smyth have identified as the main animating discourse of Irish ‘beat’ music in its formative decades, ‘creative self-expression’ – the idea that one performed music in order to explore and reveal allegedly deep emotional truths – is all too earnestly apparent in these tracks.19 Bono was writing almost all of the lyrics, but from the start the four members of U2 shared the song-writing credits, and eventually the royalties, equally.

While many English bands in this period went chasing after black sounds, mainly reggae and ska, U2 were a whiter shade of pale. A series of ‘London spies’ – talent-spotters from the big city – had previously found the band ‘gauche and formless’,20 and it’s easy to hear why. Yes, there is something interesting and different about Edge’s guitar-playing – and once he had added an echo-unit to his paraphernalia that playing would remain the band’s major sonic contribution to the rock canon over the coming decade or three. But to understand why this mediocre band was preparing to take on the world requires some understanding of what Bono contributed, other than banal lyrics and what was then still a fairly ordinary voice.

One thing was his stagecraft. He and his friend Gavin Friday (of arty band Virgin Prunes) had studied theatre techniques with a teacher, Conal Kearney, who had himself studied with the internationally famous mime artist Marcel Marceau; Irish actor and playwright Mannix Flynn, who would later go on to national fame with his robust explorations of his traumatic youth, also helped out. Bono was a ‘boy from the northside’ with a sophisticated, trained sense derived from leading practitioners of how to use his body and eyes to seduce an audience.21 Then there was his charm, a sort of face-to-face stagecraft. Bono was, by all accounts, friendly and un-aloof, his motor-mouth not suggestive of excessive calculation, despite Bill Graham’s conclusion that Bono and U2 ‘were always rather skilled at discovering people to discover them’.22 Hot Press fell into U2’s orbit, and has remained there permanently. Bono just happened to be especially good at making friends with, say, Ireland’s best music writer, Graham, and Ireland’s favourite rock DJ, Dave Fanning. Writing in 1985, Fanning, who would remain a favoured insider for decades, freely admitted that U2’s initial charm had little to do with music: it was ‘Bono’s histrionics which gave U2 an air of more substance than was suggested by the evidence of their overall performance’, he wrote. More than their records, their ‘late night rock show interviews’ on his own pirate-radio show meant that ‘insomniacs all over Dublin could quite clearly see U2’s unique passion, commitment and dedication to the idea of the potential of the song as something heartfelt and special, and the uplifting power of live performance’.23 In other words, Bono talked a great gig.

When the time came, he wove similar personal magic in London, New York and beyond. Bono ‘had the ability to persuade the interviewer that U2 were his own private discovery and that the journalist had been cast by the fates to play his own absolutely personalized role in U2’s crusade against the forces of darkness’, wrote Graham.24

Where the journalists and DJs went, other listeners followed. It’s a pop-critical cliché to say that vague lyrics like Bono’s invite you to project your own circumstances into the emotions they evoke. But in the case of U2, the invitation came embossed and with a charming, effusive personal greeting from the lyricist himself. How could anyone resist?

WAR: NEGOTIATING IRISH POLITICS

Bono and U2 were, however, stuck with their Irishness, and in the early 1980s, with violence raging in Northern Ireland and the republican hunger-strikes escalating both tension and international interest, it was not always easy to be vague about one’s views and commitments. While their near-contemporaries, Derry’s the Undertones, could skirt artfully around the Troubles of which they were indubitably children, the bombastic and moralising U2 found the crisis that they had, and had not, lived through to be a more difficult and almost unavoidable subject.

In truth, they were probably unambivalent about the Northern crisis, insofar as any people living on the island could be. In keeping with the by now established consensus of most of their class in the Republic, they probably believed the Provisional IRA to be thugs and murderers whose campaign of violence must somehow be stopped, though the worst excesses of British and, especially, loyalist-paramilitary violence evoked some distaste too. For the most part, at least in U2’s well-off and liberal circles, fundamental critiques of the Northern state established by the partition of the island in 1921 had faded, and those who attempted to raise them again were often derided as ‘sneaking regarders’ of republican violence, apologists for the IRA. This suite of views would pose little problem for U2’s entrée into culturally enlightened society in Britain, where only a few brave Irish immigrant groups and leftists were prepared to stand up, even amid occasional IRA bombs, for the right of Northern Irish nationalists to resist discrimination and state violence, and to insist that Britain withdraw its troops from Northern Ireland. But it would pose more of a problem in the US, where open adherence to ‘the cause’ was more widespread in and beyond Irish communities.

Thus, for example, U2’s plans to ride a float in the 1982 New York St Patrick’s Day parade were abandoned when they learned that dead IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands had been named as honorary grand marshal. The hunger-strikers – seeking political status in Northern prisons against a British government, led by Margaret Thatcher, that insisted on treating them as criminals – evoked great respect in the US and around the world. In Northern Ireland the respect was sufficient to see Sands elected as MP in Fermanagh and South Tyrone just weeks before he starved to death. In U2’s Dublin, however, Sands was beyond the pale, and even an association as remote as would have been represented by a then still obscure U2 on a float in that parade was more than they could bear.25

‘Of necessity, Irish rock has striven to escape into a non-sectarian space, even at the cost of being apolitical’, Bill Graham wrote with typical certainty in 1981. While this quest for safe spaces was understandable for those working in the midst of the conflict, the nature of the ‘necessity’ for a Southern-based band is never explained by the highly influential Graham. But the punishment for transgressing the rules that said music should be escapist, for engaging with the Troubles beyond bland condemnation or rocking through the heartache, is evident in the same article in which Graham makes that strange and prescriptive assertion. It’s a Hot Press interview with the great trad-rock fusion group Moving Hearts, in which Graham excoriates them for supporting the hunger-strike campaign and badgers them to clarify whether they support the IRA itself.26

The unstated assumption is that it was ‘apolitical’, just common sense, to oppose the IRA. Even if they had been inclined to do so, it would have been unwise in the Ireland of the 1980s and early 1990s for U2 to adopt anything other than this version of an apolitical stance – a studied pseudo-neutrality that was essentially an endorsement of the political status quo (or the status quo if only the thugs would stop all the killing). Certainly, the tightly enforced Dublin consensus went, there was no injustice in the North that was worth shedding blood over, and the reasons many Northern Catholics felt otherwise – from discrimination and segregation in jobs and housing to the historic splitting of the island of Ireland and the ongoing provocation of a British military presence – were largely ignored in favour of a generic deploring of violence. (The hypocrisy of this rhetorical pacifism was exposed every time its proponents refused to condemn various acts of violence by, say, the US or British government.)

The personification of this consensus was Garret FitzGerald, who served as taoiseach (prime minister) for most of the 1980s, heading coalitions between his own Fine Gael party and the Labour Party. Virtually every biography of Bono tells of his admiration for FitzGerald, who combined bristling contempt for Northern republicans (his response to a desperate delegation of hunger-strikers’ families was to ‘lay all the blame for the hunger strikers on the republican movement and to suggest an immediate unilateral end to their military campaign’27) with a determination to launch a ‘crusade’ to reduce the Catholic hierarchy’s influence over social legislation in the Republic. This was an alluring combination not merely for Bono but for a generation of Irish social liberals who saw the vaguely professorial Fitzgerald as someone who could lead the state away from the backwardness represented by Catholic nationalism.

But the hapless FitzGerald saw his crusade backfire in 1983 when anti-abortion activists successfully campaigned to have a ‘pro-life’ amendment added to the constitution, and again in 1986 when his attempt to introduce divorce was defeated. Bono and U2 were nowhere to be seen in either of these bitter referendum campaigns, though Bono had chanced an election photo-op with FitzGerald in 1982. In September 1983, just a few days after the disastrous abortion referendum, FitzGerald appointed the increasingly famous Bono as a member of a minor face-saving distraction called the ‘National Youth Policy Committee’, a new and (it turned out) short-lived initiative, chaired by a high-court judge but without any actual powers, that allegedly aimed to address the myriad social and cultural problems faced by young people in those recessionary times.28 One hagiographic biography of Bono, written long after the fact, suggests without citing any evidence that Bono resigned after a few months, in frustration at the committee’s bureaucracy,29 but there is no sign in the Irish Times archives of his doing so publicly, and thus embarrassing his friends in government. (U2 did not put all its eggs in one political basket: the hard-headed McGuinness was closer to the opposition Fianna Fail party – a fact that kept U2 close to the levers of power after 1987, when that party settled into government for twenty-one of the next twenty-four years; McGuinness himself would serve on the state’s Arts Council, an important funding body, for more than a decade.)

To paint Bono in his proper Dublin middle-class Fine Gael colours is not to endorse those who were conducting the ‘armed struggle’ in Northern Ireland. Most people genuinely abhorred the violence of the IRA. However, it is obvious in retrospect that the ongoing campaign of vilification and demonisation of Northern Irish nationalist communities during this period deepened their marginalisation and made it easier to ignore the reasons those communities supported the ‘Provos’ (Provisional IRA). And thus it prolonged the violent conflict.

It is in this context that one can see what a faintly absurd statement of the obvious it was for Bono to introduce the 1983 song ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ in concert after concert with the famous words, ‘This is not a rebel song’ – a ‘rebel song’ being, in Irish parlance, a pub-republican come-all-ye that denounces the Brits and/or celebrates the resistance to them. And yet there was a certain revisionist something-like-genius in the way that song – its writing started by The Edge and completed by Bono – appropriated republican ideas, including that of ‘Bloody Sunday’ itself, to create the impression that U2 were in some way the true rebels for the way they bravely rejected rebellion.

Bloody Sunday can refer to two events in Irish history: a date during the War of Independence in 1920 when the IRA killed British intelligence officers across Dublin, and soldiers retaliated by shooting into a Gaelic-football crowd in Croke Park, killing fourteen spectators; or an afternoon in 1972 when British paratroopers again killed fourteen unarmed civilians, this time after a civil rights march in Derry, in Northern Ireland.30 Thus the term ‘Bloody Sunday’ mainly denotes the idea, and reality, of brutal and indiscriminate state violence. The U2 song, however, says nothing about who perpetuated the scenes of carnage that it vaguely describes, and makes no reference to the state. Indeed, in its original form, in lyrics written by The Edge, the song started out with a direct condemnation of the IRA and, implicitly, of those supporting its members’ rights in situations such as the hunger-strikes that had taken place so recently when the song was written: ‘Don’t talk to me about the rights of the IRA.’31 This line is especially revealing of its writer’s ignorance, or at least his readiness to offend Northern nationalists: the innocent dead of Bloody Sunday in Derry were protesting against Britain’s internment-without-trial of suspected republicans; so in a sense Bloody Sunday’s victims, the apparent object of the song’s sympathy, had died for trying to ‘talk about the rights of the IRA’ – and of course of the many non-IRA members who had been picked up in violent military trawls of nationalist communities.

The group thought better of that ‘Don’t talk to me …’ line, which turned into ‘I can’t believe the news today’. It’s perhaps the most fateful edit of U2’s entire career, moving the song just far enough into ambiguity to ensure it would anger no one. The protagonist is someone watching the war on television, and the repetition in the song title conveys the weariness of someone observing a society that has degenerated into savagery. How long are we going to have to keep watching this, the song asks, with ‘bloody’ a curse that in Ireland and Britain commonly suggests ‘boring’ as much as it does ‘horrible’, as in the title of John Schlesinger’s 1971 film from which the track borrows its name. There are some portentous ruminations on the observers’ mediated distance from the events – ‘And it’s true we are immune / When fact is fiction and TV reality’ – and a Christian coda after the instrumental break; there’s also some powerful noise coming from the band; what there isn’t is an ounce of insight, empathy or courage.

Writing in 1987, Irish journalist Brian Trench cogently observed that the song ‘turned part of the current war in the North into an anthem for no particular people with no particular aim’. Years later, Northern Irish academic Bill Rolston, in the course of proposing a typology of how songs dealt with the conflict, persuasively assigned ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ to his third of four categories, songs of accusation, which ‘condemn the protagonists’ but concentrate their ire on republicans. The song has even been read as first proposing, then rejecting, the ‘simple republican solution’ embodied in the phrase ‘We can be as one tonight’, abandoning that in favour of a militantly Protestant cry of ‘onward Christian soldiers’.32 One recalls with some sense of irony that this was one of a set of songs that Bono wrote in response to criticism aimed at his previous song-writing of ‘not being specific enough in the lyrics’.33

U2 drummer, Larry Mullen Jr, said in 1983 that the song was born partly out of annoyance at the pub-and-pew republicanism of Irish-Americans. ‘Americans don’t understand it. They call it a religious war, but it has nothing to do with religion. During the hunger strikes, the IRA would say, “God is with me. I went to Mass every Sunday.” And the Unionists said virtually the same thing. And then they go out and murder each other.’34 But you can search high and wide to no avail for an IRA statement to the effect that it was a religious war and that God would take the side of mass-goers.

Larry’s contempt for those who viewed the Northern Irish conflict as a religious war was lacerating, albeit confused. One wonders how he felt when Bono said, years, later: ‘Remember, I come from Ireland and I’ve seen the damage of religious warfare.’35

Despite the hostility to militant nationalism and the sense in ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ of distance from the events it describes, Bono was always ready to declare that the Troubles took place in Ireland, ‘my country’. This sounded less like united-Ireland defiance of the border imposed by Britain’s partition of the island than a means of conferring credibility on U2 for their proximity to and involvement in the situation.

And however one interprets ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’, what is beyond question is that the song, and that (false) sense that U2 intimately knew whereof they spoke, played an enormous role in turning U2 into international stars. Bono’s own version of the story says that on the previous tour, for the October album, he had already begun deconstructing the Irish tricolour on stage: he tore the green and orange away to leave only a white flag, which became the constant prop for performances of ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ thereafter.36 Whether that was the origin of it or not, the image of Bono marching to the martial beat of that song with a white flag in the misty rain at a 1983 festival gig in Colorado was part of the band’s breakthrough video on MTV. For those who didn’t know much about the Irish Troubles, it seemed that this song and the way Bono performed it were saying something terribly defiant about something or other of great, albeit obscure, political importance. And few people were prepared to point out that, in reality, he was defying no one except a beleaguered, oppressed community of mainly working-class people who were already under physical and ideological assault and were themselves looking for ways to break the cycle of violence.

By 1987, U2 were big enough, and the IRA bomb that killed eleven people at an Enniskillen war memorial was horrible enough, for Bono to make very publicly explicit that the song’s ire was directed at the Provos, as well as their Irish-American supporters. In a powerful US performance on the night of that bombing, featured in arty black-and-white in the film Rattle and Hum, he took a mid-song break to declare:

I’ve had enough of Irish-Americans who haven’t been back to their country in twenty or thirty years come up to me and talk about the resistance, the revolution back home, and the glory of the revolution, and the glory of dying for the revolution. Fuck the revolution! … Where’s the glory in bombing a Remembrance Day parade of old-age pensioners, their medals taken out and polished up for the day. Where’s the glory in that? To leave them dying or crippled for life or dead under the rubble of the revolution that the majority of the people in my country don’t want.37

He then, as always, led the crowd in chanting ‘No more!’ – this time with no question about whom the words were targeting. The target most definitely wasn’t the state that had conferred those harmlessly polished medals on those old-age pensioners, perhaps, or perhaps not, for their services to the cause of nonviolence.

The truth was that this seemingly courageous, militant stance for Peace was no more than an impassioned dramatisation of the useless, war-weary but war-prolonging shibboleths of the Irish and British establishments, which cast the conflict as fundamentally the fault of a mad, blood-crazed IRA. In this respect, Bono Vox was no more than a ‘good voice’ of his adopted class, a young man whose career benefited greatly from the Northern conflict.

In a twenty-first century interview Bono indulged in considerable revisionism about this time: ‘I could not but be moved by the courage of Bobby Sands, and we understood how people had taken up arms to defend themselves, even if we didn’t think it was the right thing to do. But it was clear that the Republican Movement was becoming a monster in order to defeat one.’38 Such understanding, including an acknowledgment that Sands was courageous and the British presence in Northern Ireland constituted a ‘monster’, was, however, unspeakable and unspoken by Bono in the 1980s. Writing in the New York Times in 2010 as he visited Derry to see the British apologise for 1972’s Bloody Sunday, he was even critical of his younger self when describing his newfound respect for Sinn Fein’s Martin McGuinness, by that time deputy first minister of Northern Ireland: ‘Figures I had learned to loathe as a self-righteous student of nonviolence in the ’70s and ’80s behaved with a grace that left me embarrassed over my vitriol.’39 His studies of nonviolence had nonetheless left him strikingly unconcerned about the violence of the state responsible for the very atrocity that he so blithely name-checked in ‘Sunday, Bloody Sunday’ – the song for which he was invited to Derry that day.

His revisionism, in any case, should come as no surprise. In the years after the ceasefires of the mid 1990s Bono, U2 and most of the rest of the Irish and British establishments learned to speak a retrospective ‘peace-process’ language of respect, dialogue and inclusion. But it was not their native tongue.

And whatever the truth of the deconstructing-the-tricolour story, Bono would not always be so sensitive about the dangers of associating ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ with nationalism, even violent nationalism. On stage in Madison Square Garden in October 2001, as the US dropped bombs on Afghan cities, during that song he ‘embraced the Stars and Stripes’ and otherwise ‘reverently’ handled the US flag.40 He didn’t tear it apart.

SELF AID: CELEBRITY AT HOME

It was obvious by the mid 1980s, when Rolling Stone called U2 the ‘Band of the Decade’ – not an entirely obvious characterisation in 1985, since their five albums (including a ‘live’ one) had sold millions of copies but not reached any higher than number twelve in the US charts – Bono and the band had successfully used their Irishness as a calling card in the United States. Back home in Ireland, it was also clear that their American success could in turn be a route to domestic power and influence. But despite their increasing association with a liberal human-rights discourse internationally (see Chapters 2 and 3), U2’s interventions in Ireland were of a distinctly cautious and conservative hue. As noted above, they kept their heads down during the huge, and hugely divisive, referendum campaigns in 1983 and 1986, on abortion and divorce respectively, when Irish liberals were demoralisingly trounced.

Six weeks before the divorce referendum, however, U2 did lend their credibility and popularity to a local follow-up to the previous summer’s global Live Aid concerts. Especially given that Live Aid’s creator was Irishman Bob Geldof, and Bono had proved one of its most telegenic stars (see Chapter 2), ‘Self Aid’ was a predictable enough response to widespread populist grumbling about the readiness of celebrities, and indeed of ordinary donors, to help poor people in faraway Africa – Ireland had led the world in per capita giving to Live Aid – but not the poor on our own doorstep. The grumbling gained depth and resonance from the devastating recession that had taken hold in the Republic in the early 1980s. By May 1986, when Self Aid took place, there was anaemic growth, but no one would have mistaken Ireland for a thriving country, with Irish unemployment having hovered for years between 15 and 20 per cent, and emigration back at levels not seen since the 1950s, tens of thousands of young people, from a total population for the Republic of only 3.5 million, leaving each year.

But the organisers of Self Aid were determined not to see it become a focus for the country’s growing political anger. U2 themselves had already begun to be appropriated by politicians and pundits as a reason for the nation to be cheerful and encouraged; in the words of one historian of the period, they were seen as ‘proof that a better Ireland was possible’.41 Self Aid too, as it approached, began to look more and more like a star-studded, TV-friendly paean to the power of positive thinking. And while there were many big Irish stars involved – the Boomtown Rats doing their last gig, Thin Lizzy returning only a few months after singer Phil Lynott’s death, the London-and-Liverpool-Irish Elvis Costello – by now there was no doubt that Bono was the biggest of them all.

There was a groundswell of opinion on much of the Irish Left that Self Aid, with its emphasis on positivity and the ‘pull up by our bootstraps’ type of capitalism of much of its rhetoric, would do more harm than the little good it would achieve through fundraising for jobs-creation projects. In addition to a charitable trust that raised more than a million pounds, and to which community groups and start-ups could subsequently apply for funds, viewers were encouraged to phone in if they could offer employment themselves: thousands of dubious ‘jobs’ were thus ‘created’ by the concert/telethon.42 This sort of charade, critics argued, was letting the state and economic elites off the hook by suggesting that the economic crisis could be solved by some apolitical form of ‘self’ activity by the unemployed and employers, who suddenly discovered they could employ people and get their names on TV in the bargain. Bono hadn’t been especially noisy in the run-up to the concert, but as its most recognisable face he became the target for left-wing criticism as the day approached. Posters featuring Bono went up around Dublin and other cities, parodying the Self Aid ‘Make It Work’ slogan by declaring: ‘Self Aid Makes It Worse’.

The left-wing posters would have been insulting enough to Bono’s vanity – campaigners had chosen a less than attractive mulleted photo, though Bono had finally abandoned that hairstyle – but worse was to come. On the Thursday before the weekend Self Aid gig, listings magazine In Dublin, normally reliable in its support of U2, appeared on the stands with Bono on the cover. ‘The Great Self Aid Farce’, the magazine declared, constituted ‘Rock Against the People’.43 Inside, several pieces denounced the concert and singled out U2 for odium for allowing themselves to be used in this way. The polemics were led by the great Derry Marxist and journalist Eamonn McCann (then still a fan, later to become Bono’s most trenchant Irish critic), along with the magazine’s editor, John Waters (later to become an increasingly conservative grouch, and who rarely had another bad word to say about Bono).

Anyone who hoped that Bono might take the opportunity of the Self Aid gig to answer his critics by underlining his genuine radicalism – and there were still some in Ireland who wanted to believe in that – was to be sorely disappointed. The most political speech he made for the occasion came in the middle of a vamping little version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Maggie’s Farm’: U2 were starting their ‘exploring the blues’ period, and were checking out how their elders and betters had done it, incorporating a bit of John Lennon’s ‘Cold Turkey’ in the mix. Because many young Irish people were emigrating to Margaret (‘Maggie’) Thatcher’s Britain, Bono reckoned it would be clever to present Dylan’s great, funny, devastating broadside about power relations as an earnest plea to be able to stay in Ireland rather than emigrate. In effect, ‘I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm, coz I’m gonna stay and work on Garret’s farm.’

The result was the effective emasculation of the cocky anger of Dylan’s song, whose protagonist runs through a list of people for whom he will no longer work, making it clearer and clearer that they probably include every conceivable species of boss. Dylan’s rejection of any chance to ‘sing while you slave’ wasn’t clear enough, however, to emerge intact in Bono’s telling, as he made clear in a rather pathetic spoken interlude over the pumping riff: ‘You see I like it just where I am. Tonight that’s Dublin city, Ireland. And I prefer to get a job in my own hometown, mister.’ The American twang in Bono’s accent had rarely stood out quite this strongly. The distinctly unDublin phrasing, including the faux-proletarian ‘mister’, pointed to the other major influence at play: Bruce Springsteen was still near the height of his popularity, and the previous summer had played a huge outdoor gig at Slane Castle in nearby County Meath; U2 had even done a (reportedly dismal) cover version of his song ‘My Hometown’ during a Dublin show in June 1985.

It was striking that Bono made his watery political declaration sound such a false and borrowed note. But he had more to say. In an extraordinary bout of self-pity, he turned part of the long and winding final section of ‘Bad’ into an apparent tribute to himself. Singing over the repeating guitar figure to the tune of Elton John’s terrible, maudlin song about Marilyn Monroe, ‘Candle in the Wind’, Bono achingly intoned: ‘You have the grace to hold yourself, while those around you crawl. They crawl out of the woodwork, on to pages of cheap Dublin magazines. I have the grace to hold myself. I refuse to crawl.’44

Refuse to crawl he might, but even today the effect of viewing this outburst via YouTube may make the viewer’s skin crawl. It was clear that the attack on ‘cheap Dublin magazines’ was aimed at McCann and Waters, but to whom on earth was he directing his refusal to crawl? Was he really just declaring himself satisfied with his display of courage in belittling his critics? And this grace – then as now among his favourite words – did it come direct from God? U2 biographer Eamon Dunphy, critical by the standards of Dublin journalists but still inclined to cut Bono slack on this incident, wrote that it showed that ‘Dublin still got to them’ – that their hometown’s mode of badmouthing had a knack for getting under their skin – but also that, ‘this being Dublin’, Bono and McCann had chatted and cleared up any ‘misunderstandings’ at a party after the gig.45 What could hardly be misunderstood was that this young man had a disproportionate sense of his own righteousness.

However, Bono’s strange and chilling onstage attack may have had some effect. It would be more than two decades, until the time when U2’s tax arrangements were revealed, before there was any comparable sustained criticism of Bono in the major Irish media. (Paul McGuinness was also capable of his own brand of chilling: when in 1991 a Dublin paper rounded up a few mildly mocking comments about Bono’s lyrics for ‘The Fly’, the band’s burly manager wrote a nasty letter to the bylined journalist, calling him ‘a creep’, and CCing the chief executive of the newspaper company.46)

The main exception to Irish press quiescence in the face of Bono’s power and glory was the small investigative and satirical magazine Phoenix. While Phoenix mostly kept a close eye on the band’s business interests in Ireland, it wasn’t above teasing Bono on other fronts. When, for example, in the year 2000 the magazine reported on the legal negotiations then ongoing between Bono and a local tabloid over paparazzi shots of the singer’s sunbathing buttocks, his lawyers threatened Phoenix with prosecution under the Offences Against the State Act – generally employed against serious crime and ‘subversion’ – for revealing ‘sub judice’ material, and said they had sought the intervention of the attorney-general over the matter. Phoenix responded by reproducing the lawyers’ letter under the unusually large headline: ‘L’ETAT C’EST MOI! KING BONO INVOKES OFFENCES AGAINST THE STATE ACT’ – and by continuing to produce story after story about ‘Bono’s bum deal’.47

It was also Phoenix magazine that reported on how Bono’s wife Ali described their relationship with journalists. Ali had been contacted by an old acquaintance named Dónal de Róiste, the brother of one of her closest charitable partners. De Róiste was still fighting to clear his name more than thirty years after being unjustly ‘retired’ from the Irish army under a cloud of suspicion of IRA connections. Ali refused to help, though in the nicest possible Christian way: ‘I wish I knew a journalist that one could entrust with this cause … but I’m sorry to say I don’t at present … the nature of our position unfortunately means that we stay as removed as possible from the press.’ She continued sympathetically: ‘I am sorry that you feel so wronged. I, like you, believe in fair play and justice … which I know you will receive in the next life …’48

MOTHER: NURTURING NEW U2’S

Bono was rarely shy about where he felt U2 fit, in this life, into the history of rock ’n’ roll, the art form and the business. ‘I don’t mean to sound arrogant,’ he told Rolling Stone rather redundantly soon after their first album had appeared, ‘but at this stage, I do feel that we are meant to be one of the great groups. There’s a certain spark, a certain chemistry, that was special about the Stones, the Who and the Beatles, and I think it’s also special about U2.’49

So it is not surprising that U2 established a record label, in the mode of the Beatles’ Apple Corps, with the stated ambition of nurturing Irish talent, though it is perhaps surprising how quickly they got around to this task: they established Mother in August 1984, before they had even started playing arenas, let alone stadia, in the US (and almost exactly ten years after the death of Bono’s mother, Iris). The Beatles left the task till rather later in their development as the world’s biggest group – that is to say, when they were indisputably on the top of the world and were in a position to establish a sophisticated corporate apparatus in the heart of London, then probably the world’s pop capital – and still made a mess of it.

Perhaps the worst that can be said with certainty about U2’s label, Mother, is that it fits quite comfortably within a history of poorly performing record labels founded by artists themselves. That is not the worst that is said about Mother, however. While U2 have benefited from a compliant press in Ireland, the gossip that plays such an important role in this small, talkative society is often far less kind. One persistent and false strand of local discourse – now of course searchable on the internet – has long suggested that Mother was deliberately established, and operated, to kill off the Irish competition, to ensure that, far from a ‘next U2’ emerging from a thriving scene, Irish acts who threatened U2’s hegemony would be signed up to Mother, then mismanaged into obscurity. This false theory is the writing-large of the false story of Paul McGuinness’s malevolent impersonating phone call to promote U2 from the band’s early days, and frankly it has just as little evidence to support it. It vastly overestimates the power of U2 to affect the behaviour of a whole range of international companies that would have been delighted to make stars of an Irish ‘next U2’, and it equally underestimates the extent to which plans and intentions can go awry and astray with just a little nudge from incompetence and complacency, and no help at all from conspiracy.

But how did Mother, and the associated distribution company Record Services, even manage to offer a plausible imitation of an enterprise established to kill off promising Irish acts? The answer is somewhat surprising, given how quickly and capably Paul McGuinness and U2 had professionalised the management of their own affairs in the early 1980s. The fact appears to be that, with Mother, U2 deliberately set their sights unusually low, then lacked the commitment and professional capacity to achieve even a modest set of notional targets. A label established in the mid 1980s to help young acts in Ireland ended up with its only really notable success being the Icelandic artist Björk in the early-to-mid 1990s. Indeed, Mother may be the only cause ever associated with Bono to have been allowed to fade quietly into obscurity.

One mark of Mother’s lack of ambition was its explicitly stated determination to limit its nurturing function to getting artists’ singles out on the label. Once an act was at the stage of releasing an album, the theory and practice went, it could and should move on to another label. This was a little strange given that U2 were already themselves recognised as the latest in the long line of quintessentially album-oriented rock groups, and the 1980s as an album-oriented era like no time before or since in the history of popular music.

Irish music-industry insiders don’t need especially complex explanations for Mother’s failure. U2 may have been helping to drag the business out of the showband era, dominated as it was by cowboy impresarios and their network of dance-halls around the country, with only a thin veneer of a recording industry slapped on to this live-music infrastructure. But the dragging was slow, and the priorities of those, like McGuinness, who were doing the dragging were understandably ruled mainly by U2’s concern for their own increasing global success. Given the structures that had proliferated in the previous era, limping weakly into the economic gloom of 1980s Ireland, industry insiders recall that there simply was not the record-label expertise in Ireland to spread around another dozen young bands in the hopes of leading one or two of them to international stardom. It would have been unrealistic to think that Mother could establish a competent version of Apple Corps in Dublin with the people available in the city to staff it. Limiting Mother to the early stages of an act’s development recognised the daunting complexity of mentoring and promoting musicians beyond those stages.

But given U2’s growing global riches after 1987, when The Joshua Tree reached the top spot on album charts all over the world, Mother could eventually have afforded to import the professional capacity to set a more ambitious agenda, or indeed just to do the early-stages work more competently; indeed, according to Magill magazine in 1987, Mother was being run out of an office in the London headquarters of Island Records (where U2 had acquired a 10 per cent stake) anyway.50 Its staff never grew past a handful; its spending was a drip-drip of thousands at a time. What emerges from an overview of its history is what may seem like a surprising description for any enterprise involving Bono: ‘half-hearted’. Or perhaps, given that U2 were always generous with rhetorical support, with ‘love’, to up-and-coming bands, but failed to invest in them adequately, ‘half-assed’ is the more appropriate term: Mother didn’t put the staff in place to deliver the uplifting boost that the Irish music scene was hoping for. The result is that a list of the Irish acts that Mother signed and promoted will lead Irish readers to nod in vague recollection of a series of one-time next-big-things, and most readers outside Ireland to stare blankly: In Tua Nua, Engine Alley, Cactus World News, Hothouse Flowers … When the revamped Mother released an album by Dublin-based novelty punk band the Golden Horde in 1991 – a good three or four years after that band’s Ramones-with-pretensions joke had started to wear thin even with their core audience – it was all too clear that, in Ireland, Mother would be no more than an amusing plaything, at most, rather than a serious developer of new talent. By that time, as a knowledgable Irish journalist has recalled, ‘Bono, U2’s point man on Mother, [had] stepped aside, and [Larry] Mullen took over, resolving difficulties brought about by the singer’s reluctance to say no to people.’51 Mother stopped functioning completely by the mid 1990s, and the company was finally wound up a decade later.

Mother comes in for remarkably little discussion in either official or unofficial histories of U2. In one long interview, with Michka Assayas, Bono refers vaguely to how the band had invested in loss-making enterprises after profiting from the sale of Island Records in 1989: ‘Losing money was not a nice feeling, and you’ve got to be careful because nothing begins the love of money more than the loss of money. But on the positive side it made us take more charge and interest in our business. This was, I guess, very early nineties.’52

He doesn’t mention Mother explicitly in that context, nor does he do so in another long interview in which he discusses the mid-1980s scene that Mother was launched to promote. But, reading between the lines, it’s easy to hear him blaming the scene rather than Mother’s inadequacy for the failure of a ‘next U2’ to emerge from Ireland, at least in the form of one of Mother’s early acts, Hothouse Flowers:

We were starting to hang out with The Waterboys and Hothouse Flowers. There was a sense of an indigenous Irish music being blended with American folk music coming through. The Hothouse Flowers were … sexy, they spoke Irish and the singer sang blue-eyed soul … but, you know, Irish music tends to end up down the pub, which really diluted the potency of the new strains. The music got drunk, the clothes got bad and the hair got very, very long.53

U2 were of course doing more than ‘hang out’ with Hothouse Flowers: they were the directors of a company that had briefly taken charge of the band’s career – and indeed sent them aloft to a middling international record deal and career that never realised its promise, including a miserable spell opening for the Rolling Stones. Unspoken amid Bono’s puritanical disdain for the drunken longhairs is the plaintive question: How could we be expected to make stars of such people?

PEACE OF THE ACTION: NORTHERN INTERVENTION

In the decades after 1986, U2 didn’t involve themselves very deeply in the political life of Ireland. Bono’s 2002 endorsement of a Yes vote in a referendum on an EU treaty, for example, was not only a relatively rare intervention, but also comprised his typical and easily ignored mix of self-praise and establishment boilerplate: ‘I go to meetings with politicians in Europe, they always bring it up … I think to vote No is going to make Ireland look very selfish.’54 U2’s cultural contribution is, as we have seen, also open to some question. They played gigs in Ireland, certainly, but scarcely any more than a major rock act with a huge Irish following might be expected to do, and always stadium-sized shows in a couple of big cities, mostly Dublin. In fact, they became something of a symbol of not-being-in-Ireland, the band that provided solace and an apolitical, uncontroversial form of Irish nationality abroad for the generation of emigrants who had fled the country through the 1980s and into the 1990s, Self Aid notwithstanding.

When, in the late 1980s, songwriter Liam Reilly came to write ‘Flight of Earls’, a sentimental emigrant ballad for that generation – which Reilly saw part-accurately as more educated and mobile than previous emigrants – he naturally mentioned what everyone knew to be the generation’s preferred musical badge:

Because it’s not the work that scares us

We don’t mind an honest job

And we know things will get better once again

So a thousand times adieu

We’ve got Bono and U2

And all we’re missing is the Guinness and the rain

Reilly’s allusion was somewhat ironic, given its clear implication that the 1980s emigrants cared more for arena-rock than for folk-pop balladeers like himself. The song nonetheless joined the playlist in countless Irish bars in the US and elsewhere, and was a substantial hit in Ireland in a version by singer Paddy Reilly – reaching number one and still in the charts when U2’s ‘Desire’ overtook it en route to the top. Indeed, for all the awkwardness of its lyrics – yes he did rhyme ‘adieu’ with ‘U2’ – ‘Flight of Earls’ is more likely to get an Irish sing-along going than all but a handful of U2’s own songs, and even made something of a comeback among the new emigrants of the post-2008 era.

Bono was not a complete absentee superstar by any means. He lived in Ireland, and as an internationally recognised symbol of Brand Ireland, Bono could not resist getting involved when the Northern Irish peace process put Irish affairs in the global spotlight for the first sustained spell since the hunger-strikes. Since virtually all Irish-nationalist opinion, along with the British government and a substantial chunk of ‘moderate unionism’ in the North, was united in favour of the process and of the Good Friday Agreement that emerged from it; since elite figures in the American diaspora were on board, and Bill Clinton himself had shown strong, indeed disproportionately obsessive, devotion to resolving these Irish troubles; since there were no popular mobilisations in support of the agreement, North, South or among the Irish abroad (with their reputation for untrustworthy, uncompromising nationalism), and thus a dearth of images of enthusiasm; and since U2 had spent, by common consent, several years in the credibility doldrums with media-savvy political gestures in place of interesting musical ones (notably in Sarajevo – see Chapter 3) – for all these reasons and more, it was all too predictable that Bono would turn up for a photo opportunity at some allegedly crucial moment in the whole affair.

That moment came during the referendum campaign on the Good Friday Agreement. In May 1998, separate, simultaneous ballots were held in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland to approve the new institutional arrangements for governing Northern Ireland. The result was never in doubt – more than 90 per cent of voters in the South voted Yes, and the referendum was approved by 71 per cent of voters in the North, with the opposition coming mainly from diehard Protestant supporters of the union with Britain (‘unionists’) who opposed the agreement as a concession to IRA terrorists and a step toward a united Ireland. The main political ambition of the British and Irish governments, and of most others on the Yes side, was to see the No vote in the North beaten into a minority not merely of the whole electorate, but even of the traditional unionist side; this sort of sectarian arithmetic had no bearing on whether the referendum would be passed or not, but it might conceivably affect the credibility of the institutions to follow it, themselves reliant on power-sharing via further sectarian arithmetic. The leader of the then-largest unionist party, David Trimble, was supporting the agreement, which had arisen largely through negotiations that aimed at including Sinn Fein, the IRA’s political wing, in the process and in future governing arrangements for Northern Ireland. But the convenient fiction adopted for the occasion was that the agreement was a settlement between ‘moderate unionism’, embodied by Trimble, and ‘moderate nationalism’, embodied by the leader of the North’s Social Democratic and Labour Party, John Hume.

The extent to which this was a fiction would be shown within very few years, with both men and their parties consigned to the political margins by the electorate. But it was already obvious at the time to anyone who was paying attention to reality, particularly to the extraordinary efforts that had been made by the Sinn Fein leadership to bring militant republicans and the community that supported them into the political process – without a split that would have seen a return to large-scale violence.

Nonetheless, it was to the convenient fiction rather than the extraordinary reality that Bono lent his support. According to a biography of Trimble, Bono himself was looking for a chance to visibly ‘bring the two sides together’. As Bono told the writer, Bono said to Hume: ‘John, I don’t feel that our value here is to reinforce you with the nationalist community … It’s to reinforce Trimble with the Unionist community. If you can put something together, we’ll be happy to interface.’55

And so it was that newspapers all over the world featured a picture of Bono interfacing: holding aloft the hands of two ‘long-time enemies’, Hume and Trimble, who he brought together on stage in front of a cheering, mostly young crowd. ‘I would like to introduce you to two men who are making history, two men who have taken a leap of faith out of the past and into the future,’ he declaimed. Bono wasn’t the only one who deliberately mistook these two increasingly irrelevant men for the heroes of ‘the future’ – the same was done by that reliably misguided body, the Nobel Peace Prize committee – and it would be churlish to deny they played a considerable role in the Northern Irish peace process. They were widely regarded as the acceptable faces of the process, and Hume in particular had played an honourable role over much of the previous decade by insisting that the key to the process was involving Sinn Fein and its supporters rather than attempting, as in so many previous attempts at agreement, to marginalise them.

But as the summary photo-op of the whole affair, the crowning achievement of the peace process, the Bono–Hume–Trimble moment was bullshit, and it seems it was bullshit of Bono’s excreting. Speaking before the concert, the singer had reinforced his ‘triumph of the moderates’ message: ‘… to vote “no” is to play into the hands of extremists who have had their day. Their day is over, as far as we are concerned. We are in the next century.’56 A few years into the real, as opposed to the imagined, ‘next century’, the former IRA man Martin McGuinness was the North’s deputy first minister, serving beside the Protestant bigot the Rev. Ian Paisley, who had opposed the Good Friday Agreement: two of Bono’s hated twentieth-century ‘extremists’, going so amiably about the business of governing Northern Ireland that the press corps dubbed them the Chuckle Brothers, after a pair of British slapstick comedians.

Bono and U2 continued in subsequent years to distort the reality of that 1998 intervention. In their magisterial 2006 ‘autobiography’, U2 by U2, they incorrectly state that the referendum was on a knife-edge – Bono says ‘the signs were not good’, and Edge says it was ‘won by a very small margin, two or three points’, only after a Yes swing prompted by the concert. The actual margin in the North was more than 42 per cent. (In the same book Bono adds ignorance to distortion when he goes on to misidentify the republican dissident group who bombed the centre of Omagh town a few months later as the ‘Continuity IRA’, when anyone in Ireland who had been paying attention at all knew it was the ‘Real IRA’ – though even those paying attention might have found it hard to explain the precise distinction between the two republican splinter groups.57)

In another interview for international consumption several years after the fact, Bono called that moment ‘the greatest honor of my life in Ireland’, and called Hume and Trimble, rather ridiculously, ‘the two opposing leaders in the conflict’. He added: ‘People tell me that rock concert and that staged photograph pushed the people into ratifying the peace agreement. I’d like to think that’s true.’58 No doubt he would love to think it’s true. However, the ‘people’ telling Bono that must surely be extreme sycophants even by rock standards: of all the myths peddled by Bono’s supporters, this surely is among the most obviously and egregiously untrue, refuted by a minute’s fact-checking.

By 2012 the myth of Bono the Peacemaker had grown to absurd proportions, with his close adviser Jamie Drummond telling BBC viewers that for ‘most of the Nineties Bono was very involved in campaigning on Northern Ireland’.59 This notion would come as a great surprise to anyone who was actually involved in the peace process there, and one would like to imagine that Drummond’s ludicrous assertion would embarrass even Bono himself.

The famous Hume–Trimble photo-op, and the subsequent fate of its two political subjects, is sometimes cited as evidence of the ‘Curse of Bono’. It is of course nothing of the sort. Cynical people might argue that it is just another example of the extent to which Bono remained a conventional-thinking opportunist who could spot the shortest distance between himself and some great global publicity. Perhaps, unlikely though it seems, he was too dense to see the underlying political reality, and the inevitable ascent and key role of Sinn Fein on the Catholic-nationalist side and Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party on the Protestant-unionist side; it’s more likely that he was smart enough to ignore it, because he was never going to be able to get it into a photograph.

WHERE THE CHEATS HAVE NO SHAME: TAX TROUBLES

The desire to make lots and lots of money – just so as not to be tempted to succumb to the love of it, naturally – and the desire to visibly embody All That is Good, especially in Ireland, need not come into conflict as far as Bono was concerned. Despite Mother’s shortcomings, U2 were routinely praised extravagantly in the Irish media for their ‘commitment to maintaining their base’ in Dublin – Ireland was so gloomy for much of the 1980s and 1990s that staying there seemed counter-intuitive. The economic benefits enumerated for Ireland of having the band continue to live, record and run their businesses from their home city were never especially impressive, however.60 They were a big rock band, but that didn’t make them a particularly big business in terms of, say, employment, and no one could say if they actually attracted a large number of tourists to the city, though many visitors who came did make a pilgrimage to add graffiti to their old Windmill Lane base.

The fact is that Bono and the rest of the gang had very good reason for maintaining their base in Dublin. As an Irish journalist pithily noted: ‘Up until 2006 U2 enjoyed extraordinarily favourable tax treatment in Ireland.’61 Ireland has famously had, since 1969, an artists’ tax exemption, whereby Irish residents’ earnings from artistic work – published work, that is, not performance – were not liable to tax. This exemption was established by the notorious politician Charles Haughey, when he was minister of finance. Suspicions about how Haughey funded his lavish lifestyle trailed him through his career, and finally caught up with him in his final years in the 1990s, when a long trail of secret payments to him was revealed; the artists’ tax exemption, however, was one of the reasons that Haughey went to his grave with a ringing postscript to an epitaph that was otherwise that of a scoundrel: ‘But he was a great patron of the arts’. The artists’ exemption not only protected the meagre earnings of most Irish artists, but turned Ireland into a minor tax haven for various foreign rock stars and best-selling writers, from Def Leppard to Frederick Forsyth. Many British artists positively went native, making films and records in Ireland and engaging cheerfully with Irish public life. Given the aggressive business mentality of U2 and McGuinness, it would be surprising if this exemption were not part of the attraction of remaining in Dublin through all their years of international superstardom.

As with any tax break, those who renewed it annually and those who benefited from it could make a case for the artists’ tax exemption, even as it hugely assisted a handful of super-rich artists, for bringing various ancillary benefits to the state – such as the prospect that you might meet Elvis Costello at a party or see Irvine Welsh in the supermarket. It certainly had the effect of encouraging artistic production in the country, if that can be counted as a benefit. ‘However,’ a journalist wrote, ‘the exemption for artistic income was costing the state tens of millions of euros in forgone tax.’62 Just thirty artists accounted for nearly 60 per cent of what was theoretically lost.63 It must be said that this was small beer compared to what was sacrificed for various non-artistic corporate tax breaks, and what was ‘forgone’ with the low rate of tax on corporate profits that had attracted so many multinational corporations to Ireland. Artists were a convenient scapegoat for Ireland’s tax-haven status, which in reality had little enough to do with the arts. But throughout the period of the Celtic Tiger, perhaps because in the celebrity magazines artists were so visible among Ireland’s conspicuously rich consumers, the artists’ tax exemption came under populist pressure. Bono’s name figured frequently in the discussion, its defenders forced to defend him, as in this newspaper report from a parliamentary committee hearing: ‘An artist like U2 lead singer Bono is “priceless” and, if he left, Ireland would lose an extraordinary economic advantage, David Kavanagh of the Irish Playwrights and Screenwriters Guild said.’64 A Green member of parliament defended the scheme, saying ‘personalities such as Bono [and others] may earn large amounts of money in a particular calendar year but perhaps not earn money in the previous year or the year after’.65 This parliamentarian displayed remarkably little understanding of how U2’s financial affairs might be organised: the last year in which Bono failed to ‘earn money’, and plenty of it, was in the 1970s. On letters pages and radio phone-ins, Bono was the national poster-boy for undeserving tax-exempt artists.