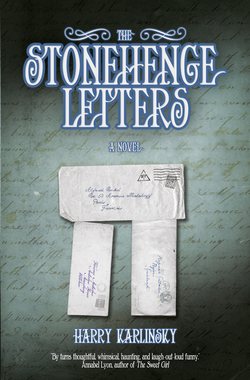

Читать книгу The Stonehenge Letters - Harry Karlinsky - Страница 9

CHAPTER 1 ALFRED NOBEL

ОглавлениеFor those readers unfamiliar with the early history of the Nobel Prizes, the man in whose honour they were named – Alfred Bernhard Nobel – was born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1833. The third eldest of four sons (two younger siblings died in infancy), Alfred’s childhood years in Sweden were spent in relative poverty. His father, Immanuel Nobel, a self-taught pioneer in the arms industry, had been forced into bankruptcy the year of Alfred’s birth. Immanuel subsequently left his wife Andriette and their children in Sweden to pursue opportunities, first in Finland and later in Russia, that would re-establish the family’s wealth. It was not until 1842 that the Nobel family was reunited in St Petersburg. By then, Immanuel had convinced Tsar Nicholas I that submerged wooden barrels filled with gunpowder were an effective means to protect Russia’s coastal cities from enemy naval attack. This was surprising, as virtually all of Immanuel’s brightly painted underwater mines failed to detonate, even those brought ashore and struck severely with hammers.

Due to the ongoing military tensions that eventually led to Russia’s involvement in the Crimean War (1853–1856), Immanuel’s munitions factory prospered and Alfred’s adolescent years in St Petersburg were privileged. With the assistance of private tutors, he became fluent in five languages and excelled in both the sciences and the arts. At age seventeen, Alfred was sent abroad for two years in order to train as a chemical engineer. In Paris, his principal destination, he was introduced to Ascanio Sobrero, the first chemist to successfully produce nitroglycerine. On Alfred’s return to St Petersburg in 1852, he and his father began to experiment with the highly explosive liquid, initially considered too volatile to be of commercial value.

Despite initial setbacks, Alfred Nobel quickly established himself as a talented chemist and aggressive entrepreneur. His most important discoveries – the detonator, dynamite, and blasting gelatin – would form the lucrative underpinnings of an industrial empire. By the time of his death in 1896, Nobel held 355 patents and owned explosives manufacturing plants and laboratories in more than twenty countries. According to his executors, his net assets amounted to over 31 million Swedish kronor, the current equivalent of 265 million American dollars.

As his legacy, Nobel directed in his will that his immense fortune be used to establish a series of prizes. These were to be annual awards for exceptional contributions in the fields of physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, and peace. The will then ended with a curious closing directive:

Finally, it is my express wish that following my death my veins shall be opened, and when this has been done and competent Doctors have confirmed clear signs of death, my remains shall be cremated in a so-called crematorium.

It was Freud who stated that there was no better document than the will to reveal the character of its writer. Nobel was terrified of being buried alive, a phobia termed taphophobia (from the Greek taphos, for ‘grave’). The triggering stimulus, at least as cited in Nobel’s conventional biographies, was Verdi’s opera Aida. Nobel had attended its European premiere at La Scala, Milan, on 8 February 1872 and was deeply affected by the closing scene. Aida, a slave in Egypt (but, in truth, an Ethiopian princess), chooses to join her condemned lover Radamès as he is about to be sealed within a tomb. Horrified by the imagery of their impending immurement, Nobel immediately developed a deep-rooted fear that he, too, was destined to die while sentient and trapped. To address his anxiety, Nobel first carried a crowbar on his person. He next relied on a ‘life-signalling’ coffin of his own design.fn6 In the end, Nobel trusted on the certainty of cremation. It was only on realising he was now at risk for being burned alive, as opposed to buried alive, that a cautious Nobel also stipulated that his ‘veins shall be opened’ prior to his cremation (i.e., exsanguination by way of phlebotomy).

Years later, Nobel was to die suddenly in San Remo, Italy. As his will, the provisions of which were unknown to others, was on deposit in a private Swedish bank, it took three days before his executors learned of his morbid last wishes. By then, Nobel’s corpse had been embalmed, a standard funerary practice in Italy during the 1890s and a process that, by good fortune, begins with bleeding the veins of the deceased.

Figure 2. The Nobel Family. Immanuel Nobel (top left), Andriette Nobel (top right), and the Nobel brothers: Robert, Alfred, Ludvig, and baby Emil (bottom, clockwise from top).

Sadly, even Nobel had recognised he was troubled throughout his life by more than an operatic death scene. Though capable of congenial social interactions and outright levity in the right company, Nobel had lived a lonely existence without a lifelong partner or children. It was a lament he would frequently share, even in letters to strangers, as evidenced by the following admission:

At the age of 54, when one is completely alone in the world, and shown consideration by nobody except a paid servant, one’s thoughts become gloomy indeed.

With bitter insight, Nobel accepted his unwanted isolation as central to his melancholic outlook and the frequent episodes of depression that were particularly prevalent in his middle years. Nobel would refer to these periods of despair as visits from the ‘spirits of Niflheim’, the cold and misty afterworld in Nordic mythology and the location of Hel, to where those who failed to die a heroic death were banished.

Remarkably, Nobel failed to consider the root cause of his isolation, which was directly attributable to the loss of the many family members and colleagues who had died sudden violent deaths (i.e., were blown to smithereens) as a result of their association with him. In 1856, the Crimean War had ended unfavourably for Russia, in no small part due to the failure of Immanuel’s ineffectual mines to cut off crucial enemy shipping lanes in the Baltic Sea. The financial circumstances of the Nobel family declined accordingly. After retreating hastily to Stockholm with only limited resources, Alfred and his father continued their experiments with nitroglycerine. On 3 September 1864, five individuals died in a horrific explosion; among the casualties was Emil Nobel, Alfred’s younger brother. To compound the tragedy, a grieving Immanuel suffered a debilitating stroke just one month later. Yet within two months of Emil’s death, Alfred was defiantly exporting the world’s first source of industrial-grade nitroglycerine. Due to the concerns of government officials about the dangers of the unstable compound, its preparation was restricted to a barge anchored on a lake located beyond Stockholm’s city limits. Despite such safety measures, a distressing loss of lives would continue to accompany the commercial production of nitroglycerine, which Nobel quickly extended by establishing factories throughout Europe. Although Nobel refused to express remorse in public (possibly on the advice of his lawyers), the deaths of so many of his employees and innocent bystanders would have a lingering impact on his sensitive disposition.fn7

Nobel’s poor physical health would also constantly undermine his fragile temperament. As a fragile and sickly child, Nobel frequented health spas while still in his late teens. Troubled by chronic indigestion, he was once diagnosed with scurvy, and for a period of months consumed only horseradish and grape juice. In his late forties, Nobel developed severe migraine headaches, and then, more seriously, the onset of paroxysmal spasms of chest pain. Though the latter symptoms were initially assumed to be hysterical in nature, he was eventually diagnosed as suffering from a debilitating form of angina pectoris. As he aged, his attacks worsened. While visiting Paris in October 1896 Nobel had a particularly severe episode. As he drolly wrote, Within two months of returning to his winter residence in San Remo, Italy, Nobel suffered a catastrophic cerebral haemorrhage. On 10 December 1896, agitated, semi-paralysed and attended only by Italian servants unable to comprehend his last words, which were uttered in Swedish, Nobel died as he had feared, trapped within his body, frightened and alone.

Figure 3. Alfred Nobel.

Isn’t it the irony of fate that I have been prescribed nitroglycerine to be taken internally! They call it Trinitrin, so as not to scare the chemist and the public.fn8