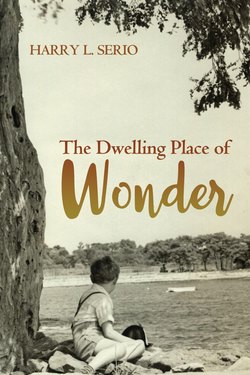

Читать книгу The Dwelling Place of Wonder - Harry L. Serio - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE ROLLING GARDENS OF PACIFIC STREET

ОглавлениеUncle Nick was the family patriarch, a title achieved mostly through longevity, although his wisdom was nothing to be trifled with. One would never know it to look at him, but within the family he was reputed to be fabulously wealthy—a fact he carefully concealed from everyone, including his only son, Louis, the banker, and his wife, Flo, who labored in a sweatshop well into her seventies when failing eyesight forced her retirement.

Nick possessed only one suit, a narrow-lapelled black worsted purchased back in the sixties to wear at the funeral of his brother, and subsequently at family funerals since. He bought a new suit that he wore to his older sister’s funeral some twenty years later, perhaps because he had become the titular head of the family.

“One man’s trash is another man’s fortune,” so they say. Nick made his fortune during the war collecting scrap metal and parlaying it into a sizeable sum. It was during this time that his ingenuity became legendary.

Rubber was a very scarce commodity. In order to make a buck, Nick removed the rubber hoses from his old Ford’s cooling system and replaced it with an intricate network of pipes and connectors. It worked beautifully. That is, until one day that a friend borrowed the car and it overheated on McCarter Highway, just outside of Newark. They pushed it to a nearby garage and lifted the hood. The attendant took one look at the pipes, which gave the appearance of a distillery on wheels and said, “You don’t need a mechanic. You need a plumber!”

When it came to auto improvisation, Nick was a genius. There was a time back in the thirties when Nick drove an old truck from Scranton, Pennsylvania to Newark, New Jersey. The tires were badly worn and the back roads were rut-filled. When the right front tire blew, Nick put on the spare. Then the left rear tire went. Fortunately he had an extra inner tube and he changed the tube and pumped it up. But when twenty-four miles from his destination, both front tires went, there was little to do.

Relying on his experience and expertise, Nick packed both tires with dirt and continued his journey with a less-than-comfortable ride.

My brother Bob, Uncle Emilio, and I visited Nick at his Pacific Street estate in the Ironbound section of Newark. It was a modest property. Bars and barbed wire protected the back yard. A “Beware of Dog” sign hung on the gate, warning of a junkyard dog no longer present. Flo was hanging out her laundry on the line. With all his money, we wondered why they didn’t have an electric dryer, or if Flo had to do all her wash by hand. Nevertheless, Nick was concerned about providing Flo with whatever convenience he could contrive. She was standing atop some moveable stairs that Nick had rescued from the junkyard. It had been used by Eastern Airlines for boarding the old two-prop planes years ago. We marveled at the application.

“Hey, that’s nothing,” he said. “Let me show you my garden.” There was nothing in the backyard except concrete and a four-car garage. He pushed open the doors of the garage and wheeled out his portable garden—sixteen barrels cut in half and mounted on roller skates. There were tomatoes and egg plants, a small fig tree, gladiolus, and other vegetables and flowers. “These kids around here, they’ll steal anything,” explained Nick. “That’s why I have to lock up my garden at night.”

After he watered his plants and positioned them where they would get the most sun, we sat on his swing for some lemonade and conversation. In spite of his gravelly voice and uneducated speech, Nick possessed a quick wit that could duel with any of the Serios. While he was born on a farm in southern Italy, the blood of the Italian Renaissance flowed in his veins.

It has been said that while the Swiss had lived for centuries in peace in their Alpine villages, all they could produce were cuckoo clocks. But the Italians who lived in the path of marauding armies and encountered violence at every turn gave us some of the world’s finest art, the greatest operas, and a system of laws and government that have become the foundation of the world’s great democracies.

Adversity is still our greatest teacher, ingrained in the fabric of our evolutionary nature. We adapt or perish. But sometimes, I wonder—to come four thousand years from the hanging gardens of Babylon to the rolling gardens of Pacific Street—whether or not it is worth it.

Still, Nick’s ingenuity and ability to take what was given to him and transform it into a functional accessory serves as an example of how the human species has endured.